An update on what we’ve learned from our funded academic research and the new questions we seek to answer

Overview

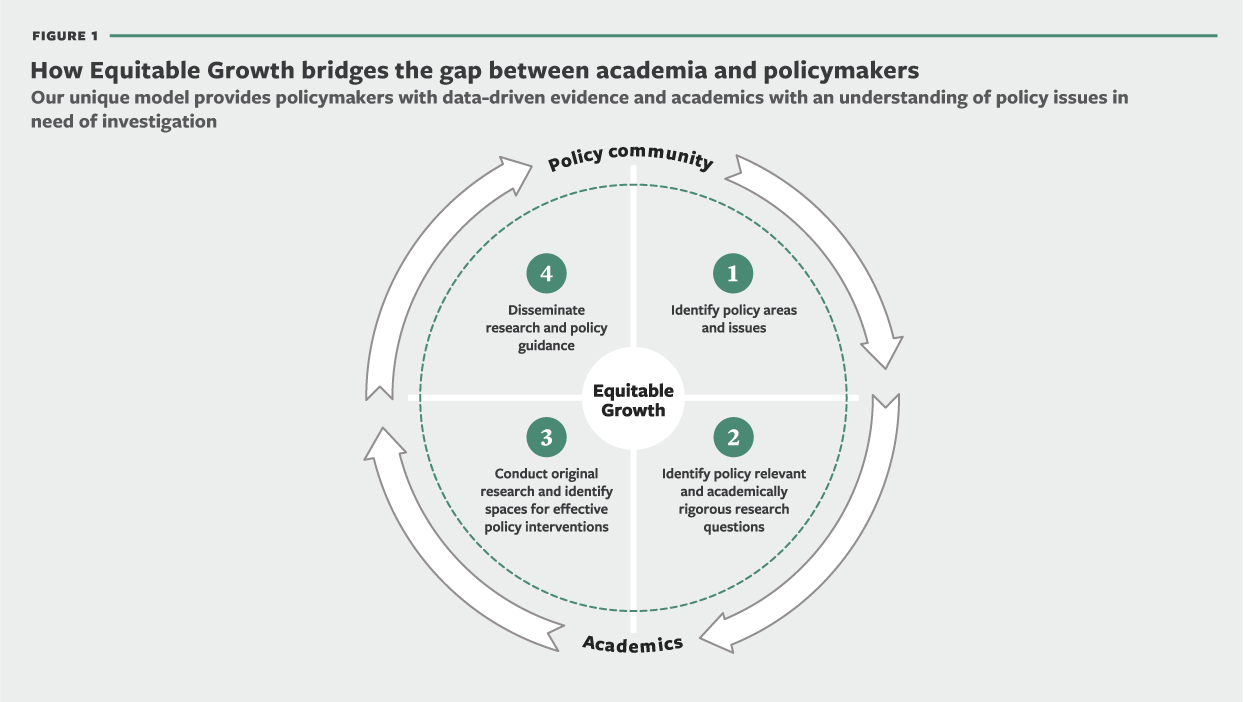

The Washington Center for Equitable Growth is a nonprofit research and grantmaking organization dedicated to advancing evidence-backed ideas and policies that promote strong, stable, and broad-based economic growth. For 7 years, our grant program has supported scholarly research at U.S. colleges and universities aimed at deepening our understanding of how inequality affects economic growth and stability.

We place a priority on research that is relevant to policy debates, abetting the development of evidence-based policies. Equitable Growth’s in-house team of more than 40 staff helps bridge the gap between researchers and the policy process, engaging policymakers, as well as the media, with the evidence and data from our cutting-edge research. And we are committed to increasing diversity in the economics profession and across the social sciences because we recognize the importance of diverse perspectives in broadening and deepening the research on inequality and growth.1 Equitable Growth seeks to support more Black scholars and to fund more research based on the lived experience and legacy of structural racism, and our programming aims to support scholars from underrepresented groups in the social sciences up and down the career ladder to promote greater diversity.

Since 2013, Equitable Growth has provided more than $6 million in grants to more than 200 researchers. In 2020, we announced a record $1.07 million in grant funding. The funds went to 19 faculty grants and 12 doctoral grants supporting Ph.D. student researchers. Separately, we awarded more than $250,000 in grants for new research on paid leave, with a focus on medical and caregiving leave and on employer responses to paid leave.2

Equitable Growth supports inquiry that relies on many kinds of evidence and a variety of methodological approaches. We value interdisciplinarity. Much of the research we fund focuses on measurement and data collection and employs empirical techniques that can show causality, though we are also interested in descriptive work, including from a historical perspective. Our Steering Committee, consisting of former top policymakers and leading academics, guides our research priorities, helps write our annual Request for Proposals, and reviews and approves grant decisions. Its members are:

- Princeton University economist and former Vice Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Alan Blinder

- Michigan State University economist Lisa Cook

- Harvard University economist Karen Dynan

- Harvard University economist and former White House Council of Economic Advisers Chair Jason Furman

- University of California, Berkeley economist Hilary Hoynes

- Princeton University economist Atif Mian

- Former White House Chief of Staff and Co-founder of Equitable Growth John Podesta

- Nobel Laureate and Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist Robert Solow

Former Equitable Growth President and CEO Heather Boushey and former Federal Reserve Chair and White House Council of Economic Advisers Chair Janet Yellen both departed the committee to serve in the Biden administration. Emmanuel Saez of the University of California, Berkeley and Janet Currie of Princeton University also cycled off the committee recently, after 7 years of service.

Our 2021 Request for Proposals launches our eighth grant cycle. Our latest RFP illustrates how our thinking about inequality has evolved based on the evidence, as well as our increasing ability to build upon our existing research to pinpoint new questions to pursue.3 The RFP requests proposals in four core areas: human capital and well-being, the labor market, macroeconomics and inequality, and market structure. We believe research in these areas is crucial for understanding the relationship between inequality, growth, and well-being.

As described in last year’s annual report, these categories have evolved over time. That is certainly true for our new RFP, which reflects changes in a few ways.4

First, this year’s RFP reflects an increased emphasis on the role of structural racism perpetuating and hardening economic inequality. As the RFP states:

There can be no understanding of persistent and rising economic inequality that does not acknowledge racial inequality. We are interested in how structural racism manifests in policies and institutions, and what the effects are for overall economic growth and stability, as well as for individuals from historically marginalized groups.

Second, an area of inquiry that reflects a new emphasis for Equitable Growth is the relationship between the environment and economic inequality. We want to explore in-depth the interaction between climate change and economic inequality, and the impact of climate change throughout our research categories, especially in macroeconomics and inequality.

One other small but significant change is a revised title for the category covering our macroeconomic questions. It is now called “macroeconomics and inequality” to reflect our specific interest in the role of inequality in the dynamics of the macroeconomy.

Following are descriptions of our four funding channels, with recent examples of research and new grants, as well as information about the questions we are looking to answer in the 2021 RFP.

Macroeconomics and inequality

Equitable Growth supports research on the effects of the historic levels of inequality on the economy, especially how high inequality limits the effectiveness of current policy tools and on the impact of monetary, fiscal, and tax policies on the level and distribution of income and wealth. We are interested in what policies could lead to more equitable, sustainable, and broadly shared growth, and in the effect of racial disparities and discrimination in the economy. And, for the first time, we are emphasizing the impact of climate change on economic growth and on the distribution of income and wealth. This area of research is critical to understanding how economic inequality affects growth and stability. Finally, an important part of the work we support in this area is research that continues to improve the methods by which we measure economic inequality.

In 2020, previous Equitable Growth grants for macroeconomic research led to a number of working papers and other writing, including:

Monica Garcia-Perez of St. Cloud State University and Sarah Elizabeth Gaither and grantee William Darity Jr. of Duke University wrote a working paper that explores the connection between credit scores, race, and incarceration history.5 Expanding on the 2017 National Asset Scorecard for Communities of Color study of Baltimore, Maryland, the researchers found that having been incarcerated had a negative impact on individuals’ credit scores for all races. But they also found that there was a significant difference based on race such that even though Black individuals with no history of incarceration have greater assets and less debt than White individuals who have been incarcerated, their credit scores are only modestly higher. While the authors emphasize that their sample size was small, the research suggests a relationship between race and credit scores.

A working paper by Equitable Growth’s former Dissertation Scholar Christina Patterson, now at the University of Chicago, shows that the unequal impact of recessions on workers based on such factors as income level, race, and age amplifies the aggregate shock imposed on the economy by an economic downturn.6 Because Black, young, and lower-income individuals have a greater marginal propensity to consume—meaning they have a greater tendency than average to consume rather than save—when they are hit harder by job losses, the economy overall suffers more than if the economic pain were spread evenly through the labor market. This paper is especially relevant as policymakers consider relief measures for the coronavirus recession, including measures to boost demand in the economy.

New grants awarded in 2020 continue to build on this work in several ways. Greg Kaplan of the University of Chicago will carry out a project that is part of a broader agenda designed to improve our understanding of the varying impact of macroeconomic shocks and policies on workers at all income levels. He will develop both theoretical and empirical evidence regarding labor income that will help make possible quantitative macroeconomic models for studying these distributional effects, which existing macroeconomic models can do only in limited ways.

Dominik Supera of the University of Pennsylvania and Martina Jasova of Barnard College will use a 2020 Equitable Growth grant for research intended to improve understanding of the effects of monetary policy on inequality. They will use Portuguese administrative data to obtain fine-grained estimates of the effects of monetary policy on the distribution of both labor income and firm credit outcomes.

Consumption dynamics are central to macroeconomics, but we do not know enough about the sensitivity of consumption to fluctuations in monthly income. We also need to better understand how these differences in consumption vary by wealth and, because of the very wide racial wealth gap, by race. A 2020 grant to the University of Chicago’s Peter Ganong, Damon Jones, and Pascal Noel will support their research on how income shocks affect consumption and how that varies by race and wealth.

Pedro Juarros and Daniel Valderrama of Georgetown University received a 2020 doctoral grant for research on the “innovation dividend” of fiscal policy. They will examine how geographic concentration of innovation affects regional economic growth in the United States. The researchers will explore how local fiscal stimulus in the form of defense spending impacts both innovation and economic growth.

A second 2020 doctoral grant focused on place-based policies was awarded to Eva Lyubich of the University of California, Berkeley, who will explore whether people’s energy consumption choices are constrained by where they live and whether that, in turn, means traditional models of the efficiency of carbon taxation are incorrect. She will examine the roles of factors such as climate, income inequality, segregation, and public disinvestment.

A doctoral grant to Lina Yu of Georgetown University will support research on how U.S. monetary policy affects firms’ employment differently, based mainly on their age and size. This work can help monetary policymakers in their effort to promote maximum employment.

How to measure economic inequality

As noted in our previous annual report, understanding the U.S. economy requires data measurement, and Equitable Growth provides significant support for research that improves the measurement of economic phenomena. An early grant to Stanford University’s Jonathan Fisher, David Johnson of the University of Michigan, Timothy Smeeding of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Jeffrey Thompson of the Federal Reserve System supported their project looking at the joint distribution of income, consumption, and wealth to think about inequality in new ways. They find that when examined through a lens of two or three of these factors together, inequality is increasing more rapidly than when it is examined for only one factor.7

In 2017, we provided support for the first WID.world conference to help launch their World Inequality Report, which synthesized the research on inequality across dozens of countries.8 Additionally, Equitable Growth is helping to support the Global Income Dynamics project, headed by Fatih Guvenen of the University of Minnesota, Luigi Pistaferri of Stanford University, and Princeton University’s Gianluca Violante, which is assembling panel administrative data across several nations to measure inequality, income volatility, income mobility, and more in an internationally comparable way.9

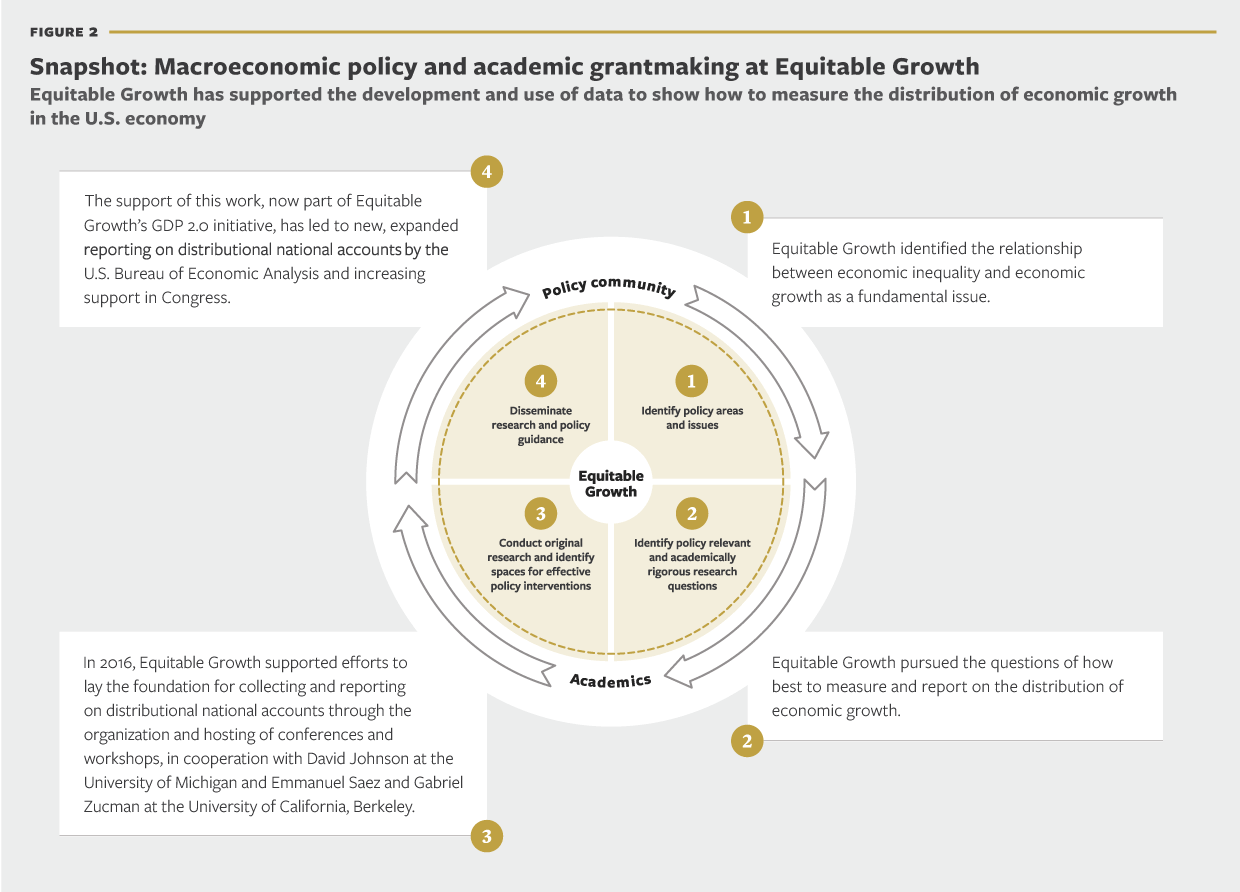

These research projects help power Equitable Growth’s own GDP 2.0 initiative,10 which makes the case that the Bureau of Economic Analysis at the U.S. Department of Commerce should measure the distribution of income growth as routinely as it measures aggregate growth.11 That work has had a significant impact on BEA, which has begun to provide distributional data for the U.S. economy and plans to issue regular updates. Among many scholars who have contributed to this work, especially notable are the pioneering efforts of Thomas Piketty at the Paris School of Economics, former Equitable Growth Steering Committee member Emmanuel Saez at the University of California, Berkeley, and Equitable Growth grantee and UC Berkeley economist Gabriel Zucman, who together have created a series of distributional national accounts dating back to the 1910s.12

In 2020, we awarded a new grant to our former Dissertation Scholar Jacob Robbins, now at the University of Illinois at Chicago, that will deepen our ability to measure wealth inequality. Capital gains are one of the largest components of income at the top of the wealth distribution, and the assets that give rise to those capital gains play a key role in measuring wealth inequality. This project will construct a new dataset to measure the holdings of public equities and fixed-income assets for all individuals in the United States, allowing for more accurate estimates of wealth inequality, including new estimates of top-end wealth inequality.

How taxes affect economic inequality and growth

Equitable Growth’s longstanding interest in the role of the federal tax system in affecting both inequality and growth began in 2015, when we convened a group of top scholars on the subject to help us determine where the organization could have the greatest impact in terms of research and policy. In a paper summarizing the discussion at that convening, “Taxing Capital,” David Kamin of New York University School of Law provided a roadmap, laying out the research needed on the taxation of corporations, capital gains, and wealth.13

In 2017, Equitable Growth awarded a grant to Stanford University’s Luigi Pistaferri, who used wealth and income tax data collected in Norway to better understand wealth inequality by studying how wealth accumulates and how it is distributed across individuals and households.14 This research was published by The Econometric Society in its journal Econometrica and a preliminary version can be found in Equitable Growth’s working paper series.15 In 2018, grantee Juliana Londoño-Vélez, who has since joined the faculty of the University of California, Los Angeles, received a doctoral grant to estimate the impact of wealth taxes on reported wealth and on the use of tax-evasion strategies, making use of data from Colombia.16

Equitable Growth also helped support a paper by Harvard University’s Stefanie Stantcheva and co-authors Ufuk Akcigit of the University of Chicago and Salomé Baslandze of the Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance on taxation and the international mobility of inventors.17 The authors found that migration decisions of inventors with the greatest number of high-quality patents are influenced by top tax rates, with higher tax rates in a country reducing the number of such inventors in that country.

These grants are emblematic of the research needed to understand how wealth inequality affects economic growth and how the taxing of wealth could play a role in reducing economic inequality. These are all big questions that policymakers are grappling with today, especially as a new administration takes office in early 2021.

See Figure 2 for a visual understanding of how our macroeconomic grantmaking and policy research help connect academic research to important policy questions.

Equitable Growth’s 2021 Request for Proposals on macroeconomic policy

Our core questions of interest in the macroeconomics and inequality channel are:

Macroeconomics and inequality

What are the effects of the historic levels of inequality in the economy, and what policies could lead to more equitable, sustainable, and broadly shared growth? How can macroeconomics research more fully take into account the economic, social, and environmental benefits and costs of addressing the consequences and risks of climate change? What are the implications of inequality by income and wealth, across geographies and different demographic groups? What is the relationship between wealth accumulation and the intergenerational transfer of wealth on intra- and intergenerational economic mobility? Equitable Growth is particularly interested in how racial disparities and discrimination in the economy reduce the well-being of historically marginalized groups, as well as the overall economy.

Areas of interest include but are not limited to:

Monetary, fiscal, and tax policy

Does inequality make existing policy tools less effective? Would more automatic stabilizers improve the toolkit of policies to fight recessions? What are the distributional effects of monetary, fiscal, and tax policy, and do they affect large-, medium-, and small-sized firms or different demographic groups differently? Does inequality create financial vulnerability among households that influence the business cycle, and are some racial groups more likely to experience persistent scars from recessions than others? What is the incidence of different taxes, and how would potential reforms affect inequality in incomes, wealth, and other measures of well-being?

Macro-finance

What is the long-run impact of high inequality on financial markets and asset prices? How should fiscal and monetary policies take into account the macro-finance linkages that result from inequality? Can certain macro policies worsen wealth inequality through their impact on financial markets?

Climate

How do the macroeconomic impacts of climate change affect economic growth over both the short and long run, and how do the effects of macroeconomic changes brought about by climate change differ by race, location, income, and age? We are particularly interested in the creation of new public datasets and economic modeling that take into account benefits and costs of climate change mitigation and adaptation, along with evaluation of the tail risks. How does increased risk of economic instability from climate change and economic inequality affect the power of macroeconomic tools?

Political economy

Is inequality challenging the effectiveness of political institutions? What is the relationship between U.S. domestic economic inequality and global economic integration? What are the implications of increased income and wealth inequality for public policy, and how do public policies affect these relationships?

Academic letters of inquiry are due by 11:59 p.m. EST on February 7, 2021.

If invited, full proposals will be due by 11:59 p.m. EDT on May 9, 2021.

Dissertation Scholars program applications are due by 11:59 p.m. EST on February 7, 2021.

Doctoral/postdoctoral proposals are due by 11:59 p.m. EDT on March 28, 2021.

Funding decisions will be announced by July 2021. We anticipate that funds will be distributed in early fall 2021, though the timing of disbursement depends in part on the particulars of the project and the researcher’s home institution.

Human capital and well-being

Equitable Growth investigates the impact of inequality on the development of human capital and well-being in the U.S. economy. In previous years, we combined human capital with the labor market as a core area of our grantmaking, but now, we believe human capital and well-being deserve more focused attention. The high priority we place on this set of issues stems from an understanding from decades of economic research that human capital—the education and skills developed by workers and potential workers throughout their lives—is fundamental to the potential of the economy, families, and society. As such, we are also deeply interested in policy mechanisms that can mitigate the consequences of inequality on human capital development and well-being.

In our grantmaking on this issue over the years, we’ve asked about the extent to which income, discrimination, social and labor market institutions, and neighborhoods affect human capital development and therefore future economic outcomes. In recent years, our research priorities deepened to include a number of specific questions about intergenerational mobility, including the effect of childhood circumstances such as income and neighborhood, as well as the maintenance of safety net programs, on adult outcomes.

There is much evidence on the importance of investments in health and education early in life for the development of human capital, which improves mobility prospects, but there is less research into how structural changes in the labor market and in society might be obstructing upward mobility for current and future generations. We also pay increasing attention to economic stability for families, focusing on the impacts of income volatility, erratic work schedules, and changing family circumstances. We want to know how all these issues affect both well-being today and human capital development tomorrow, and ultimately economic growth and stability.

The research grants and findings highlighted in this section of the report demonstrate how data-driven academic research can point out the importance of human capital and well-being in social and economic arenas. They generally fall into the four categories listed here. While racial inequality has always been central to this area, we add it here to show grants and research specifically focused on the issue of race:

- Productivity and the safety net

- Intergenerational mobility

- Family economic stability and well-being

- Racial inequality

In each of these subject areas, Equitable Growth-funded academics are answering important questions about the links between human capital and well-being and U.S. economic growth.

Productivity and the safety net

Equitable Growth-funded research is investigating human capital development that supports stronger economic productivity. One important early grant by Equitable Growth, alongside follow-up funding, supported a research agenda that examined how opportunity influences innovation and growth, carried out at Harvard University’s Lab for Economic Applications and Policy under the direction of Raj Chetty. The grants supported a series of influential research papers, including “Who Becomes an Inventor in America? The Importance of Exposure to Innovation,” by Chetty and his Harvard colleague (now at the University of California, Los Angeles) Alex Bell, Xavier Jaravel of the London School of Economics, Neviana Petkova of the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Tax Analysis, and John Van Reenen at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.18

These researchers detail four intriguing attributes of how economic inequality impacts innovation:

- Children from families whose income puts them in the top 1 percent across the United States are 10 times as likely to become inventors as those from below-median income families.

- Examining race and gender reveals similar gaps.

- Differences in innate ability explain relatively little of these results.

- Exposure to innovation during childhood makes a child considerably more likely to become an inventor.

These findings have powered an array of follow-up research, some of it being conducted by Equitable Growth grantees.19

Recent research also suggests that the social safety net plays an important role not only in promoting well-being but also in supporting human capital development.20 This research, by Equitable Growth Steering Committee member Hilary Hoynes of the University of California, Berkeley and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach of Northwestern University, shows that childhood safety net programs, including Medicaid, the Earned Income Tax Credit, the Child Tax Credit, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (formerly Aid to Families with Dependent Children), have lasting positive effects on the lives of poor children. While this work was not funded by Equitable Growth, the organization, in light of the significance of the research, awarded Hoynes a 2019 grant to study with co-authors the long-term effects of different types of welfare reforms.21 Our hope is that this study can shed light on the implications of funding social welfare programs today on our nation’s human capital tomorrow.

This work continues with a 2020 doctoral grant to Derek Wu of the University of Chicago, who will use changes that were made in Indiana’s welfare system in 2007 to examine the short- and long-run impacts of being suddenly removed from critical government safety net programs, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Medicaid, and the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program.

Intergenerational mobility

Intergenerational mobility is an important area for grantmaking at Equitable Growth because it is key to strong, stable, and broad-based economic growth and well-being. The work of grantees Trevon Logan of the University of California, Santa Barbara, Bradley Hardy of American University, Rodney Andrews of the University of Texas at Dallas, and Marcus Casey of the University of Illinois at Chicago exemplifies our approach to this issue. The four researchers will measure the correlation between historical residential segregation and contemporary intergenerational mobility.22 Their preliminary findings, presented by Logan at an Equitable Growth event in 2018, indicate that places with higher historical segregation have lower contemporary intergenerational mobility.23

Work by Ellora Derenoncourt of the University of California, Berkeley also examines the role of geography and community and intergenerational mobility.24 In a project funded by Equitable Growth, Derenoncourt finds that policy changes in northern cities in response to the Great Migration of African Americans out of the South in the 20th century—including increased spending on policing—changed the environments in which children grew up and can explain 43 percent of the upward mobility gap between Black and White men in those cities today.

These and other findings are helping policymakers understand the importance of historic and contemporary economic policies that contribute to enduring economic inequality. And in 2020, Equitable Growth funded new research that will further examine these issues.

A grant to Martha Bailey of the University of California, Los Angeles and Paul Mohnen and Shariq Mohammed of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor will help them carry out a massive data undertaking: to produce a database of intergenerational mobility rates going back to the beginning of the 20th century. Previous work provides data only as far back as 1940. Moreover, by expanding the sources of data, the researchers will significantly enhance the quality of data for all years, enabling them to study differences across states, race, and gender.

Fabian Pfeffer of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor will use a 2020 grant to build a new national data infrastructure to measure the distribution of wealth and its contribution to economic inequality across generations. This research is critical to understanding inequality, as wealth inequality is much higher than income inequality.

Research shows how important college is to upward economic mobility. Community colleges can be a cost-effective path toward a 4-year degree, and some states and institutions provide debt-free tuition assistance in the final 2 years for those who transfer, as they do for 4-year students. But there is virtually no research specifically on the impact of that assistance on transfer students. A 2020 grant will support Cliff Robb and Fenaba Addo of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who will use the Wisconsin Promise Tuition grant program to ascertain the impact of this program on persistence, degree attainment, and other measures for low-income Pell Grant-eligible students. Their research promises to improve our understanding of how postsecondary education is supporting or inhibiting intergenerational mobility.

Family economic stability and well-being

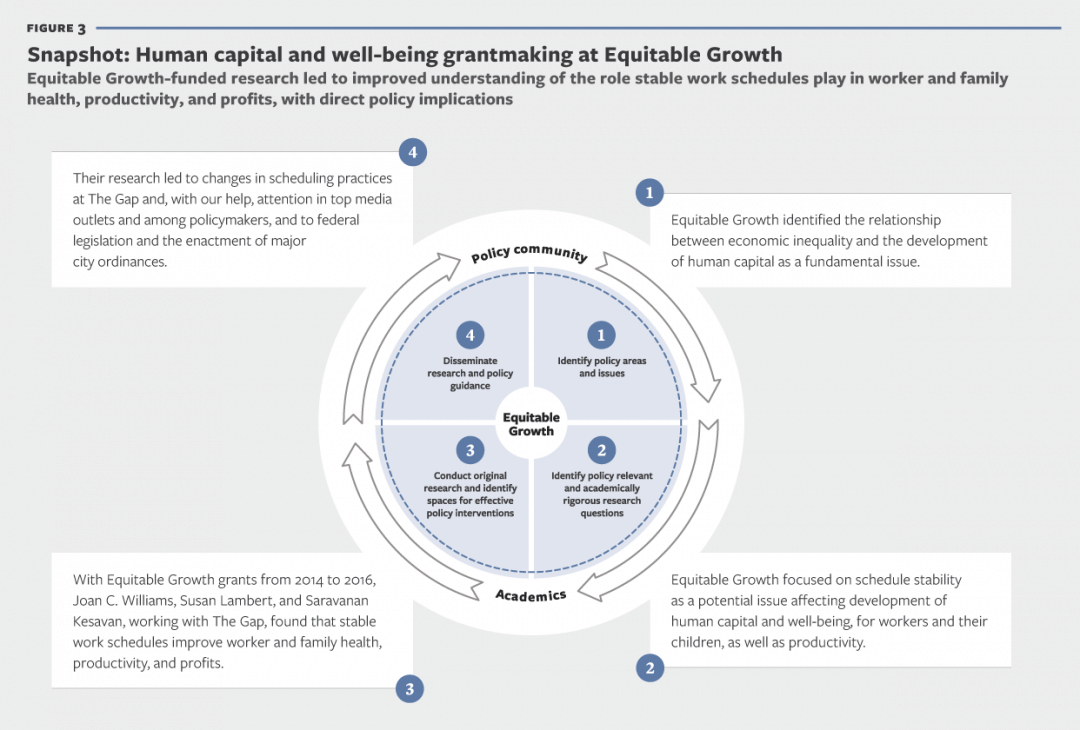

Equitable Growth recognizes the importance of family economic stability for the development of human capital (for parents and their children), as well as for the well-being of individuals and families and the broader U.S. economy. One common labor practice with significant and broad-ranging negative consequences is precarious scheduling. Research on this issue supported by Equitable Growth is increasing the interest of policymakers in policies to support more stable scheduling practices.

In our first year of grantmaking, Equitable Growth supported research to address the impact of unstable work schedules on human capital and well-being. Beginning in 2014, we funded research by Joan C. Williams of the University of California Hastings College of the Law, Susan Lambert of the University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration, and Saravanan Kesavan of the University of North Carolina Kenan-Flager Business School to work with the Gap Inc. clothing store chain to determine the consequences of unstable work schedules in its retail outlets on workers’ families, health, and productivity, and on the company itself.

This groundbreaking research, which is ongoing, shows the significant consequences of precarious scheduling on workers’ families and their own health, productivity, and morale, as well as on the company’s bottom line.25 And it has led to The Gap making significant changes to its scheduling practices.26

A 2015 grant to UC Berkeley’s Daniel Schneider (now at Harvard University) and UC San Francisco’s Kristen Harknett to investigate a proposed change to Walmart Inc.’s scheduling practices provided early funding for what has developed into the Shift Project.27The authors produced a number of insightful papers exploring the impact of unpredictable schedules. One is on worker health and well-being.28 Another is on job turnover and downward wage mobility.29 A third is on material hardship for workers.30 And two others are on the impact of unstable schedules on the children of workers, including on the quality of child care and on child behavior.31

In 2019, Equitable Growth announced three new grants on the issue of work schedules, building on the increasing evidence that unstable schedules are affecting economic stability and family well-being significantly. One grant supports research that identifies the consequences of scheduling regulation for workers with young children.32 Another will examine the consequences of unpredictable scheduling for workers and firms.33 And the third grant will document the extent to which employers compensate workers with low-quality schedules by offering higher pay.34

This year, a 2020 doctoral grant to Joanna Venator of the University of Wisconsin-Madison will support her work to examine how Unemployment Insurance policies interact with job search behavior in dual-earner households in the United States. The researcher will explore the impacts of Unemployment Insurance benefits for workers who leave their jobs due to their spouse getting a job that requires relocation. This study will seek to explain whether and how access to Unemployment Insurance influences household decisions about migrating long distances. It will also measure the extent to which access to Unemployment Insurance enables workers to obtain higher-wage jobs after a move.

Racial inequality

In addition to the other grants for which the research addresses racial inequality, two 2020 grants specifically address race-relevant issues. Andria Smythe of Howard University received a grant for research that promises to advance our understanding of employment scarring by examining the racial differences in long-term consequences of deep U.S. economic downturns for those who are relatively young when a recession hits. This research, which has obvious relevance to the current downturn, can provide insight into the long-run effects on Black and Hispanic youth who resided in regions where the recession was deepest, adding a critical racial component to our understanding of the scarring effects of recessions on young workers.

We awarded a 2020 grant to Spencer Banzhaf of Georgia State University and Randall Walsh of the University of Pittsburgh to investigate the relationships among race/ethnicity, income, pollution, and human capital in Pittsburgh from 1910 to 2010. Because of the dramatic decline in the city’s level of pollution due, in part, to the decline of the domestic steel industry, the city provides a natural laboratory to explore sorting by race in housing that leads to inequality in pollution exposure and the effects of such exposure on adult income.

These and other grants in Equitable Growth’s portfolio of funded research are helping policymakers identify solutions that will lead to the development of human capital and support the well-being of workers and their families, as well as enhance productivity.

See Figure 3 for a graphic display of how our sets of investments in human capital and well-being are playing out in academic and policy arenas.

Equitable Growth’s 2021 Request for Proposals on human capital and well-being

Our core questions of interest in the human capital and well-being channel are:

Human capital and well-being

How does economic inequality affect the development of human capital, and what are the impacts on the health and stability of the macroeconomy? To what extent can the institutions that support the development of human capital mitigate inequality’s potential effects and enhance well-being and current and future economic productivity? Through what channels do these effects occur? How does structural racism impede the development of human capital?

Areas of interest include but are not limited to:

Human capital development

How does inequality affect the development of human capital across gender, race, ethnicity, and place, as well as across income, earnings, or wealth distributions? What policies may be effective in addressing the impacts of structural racism on the development of human capital? How are climate change and other environmental factors affecting human capital development, and are there differences across groups? What are the barriers and facilitators to high quality child care—including home-based and informal care—in supporting the well-being of children, workers, and families, and are there differences across groups?

Human capital deployment

What role do public policies—such as labor market regulations, social insurance, and safety net policies—play in individual and family well-being, labor force participation, and consumption? What policies may be effective in combating discrimination and other structural impediments to the deployment of human capital? How does the availability of affordable child care affect access to and returns to work for workers with children and the child care workforce?

Intergenerational mobility

What policies or structures, including structural racism, limit intergenerational mobility, and through which mechanisms? What changes may be effective in supporting upward mobility, particularly out of poverty? What characteristics of neighborhoods have a causal effect on the development of human capital and on intergenerational mobility? How are climate change and other environmental factors affecting intergenerational mobility? Which place-based programs or interventions are most effective in promoting economic mobility, and for whom? Equitable Growth is interested in both contemporary and historical approaches to these questions.

Academic letters of inquiry are due by 11:59 p.m. EST on February 7, 2021.

If invited, full proposals will be due by 11:59 p.m. EDT on May 9, 2021.

Dissertation Scholars program applications are due by 11:59 p.m. EST on February 7, 2021.

Doctoral/postdoctoral proposals are due by 11:59 p.m. EDT on March 28, 2021.

Funding decisions will be announced by July 2021. We anticipate that funds will be distributed in early fall 2021, though the timing of disbursement depends in part on the particulars of the project and the researcher’s home institution.

The labor market

The 2018 grant cycle marked the first year that Equitable Growth’s grantmaking included a separate labor market category, though since our founding, we had supported research on the labor market through our human capital channel. The shift in emphasis was, in part, a recognition that labor income accounts for more than two-thirds of national income, and that the operation of the U.S. labor market—how markets match skills to jobs, how wages are set, and how firms improve productivity through their management of employees—is key to economic growth.

Further, since labor income is how most people support themselves and their families, the workings of the labor market are a crucial determinant of most people’s well-being. Equitable Growth’s research in this area explores how inequality affects the labor market and how the labor market does or does not generate equitable growth.

The establishment of a separate category reflects the significance we attach to the changes taking place in the U.S. labor market, including:

- The role of technology in the organization of and returns to work

- Changes in employer-employee relationships and new types of work arrangements

- The increases in state and local minimum wages in the face of inaction at the federal level

- Wage setting by firms

- The effects of discrimination in the labor market

- Declining worker power and the future of organized labor

- The effects of firm concentration on decreased employer competition for workers

We examine how these factors may reinforce each other and, in turn, may affect how wages are set and how workers are able to deploy their human capital, with implications for the equitable distribution of economic growth and intergenerational mobility.

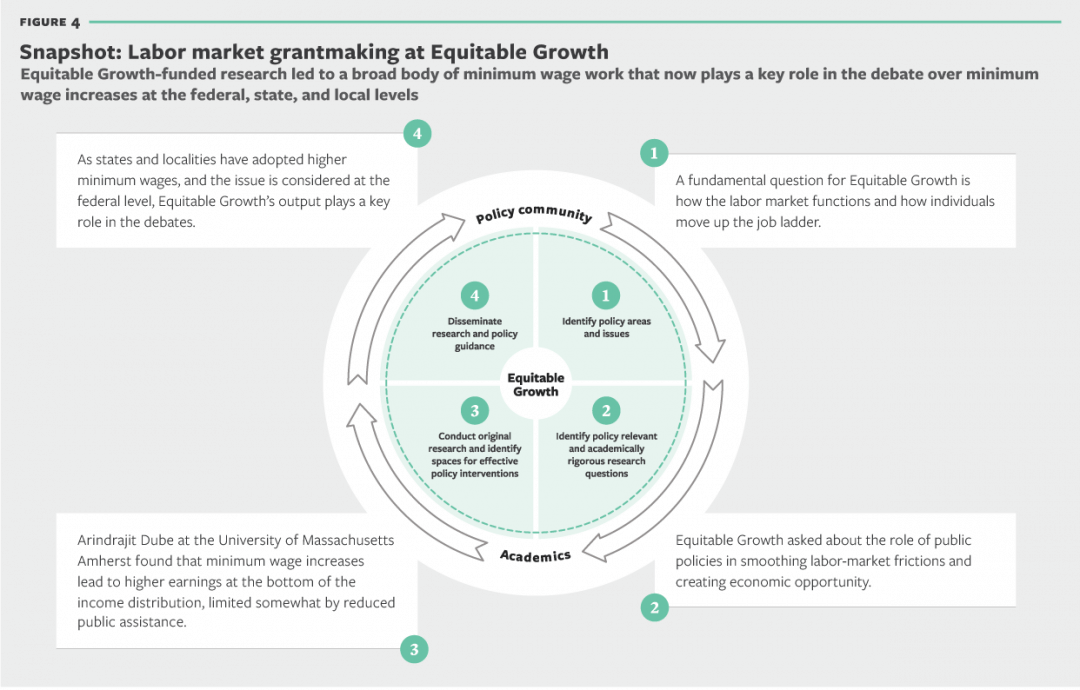

Minimum wage

Minimum wages are a longstanding topic of economic research. Numerous states and cities are raising their own minimum wages above the federal minimum wage, providing considerable opportunity to examine the consequences of minimum wage increases. Equitable Growth is associated with a range of research seeking to determine the overall impact of minimum wage increases on incomes, on employment, and on businesses.

Equitable Growth Research Advisory Board member and grantee Arindrajit Dube of the University of Massachusetts Amherst finds that increased earnings at the bottom of the income distribution are the result of minimum wage increases, with the effect limited somewhat by reduced eligibility for public assistance.35 A working paper by U.S. Census Bureau economists Kevin Rinz and John Voorheis, both of whom had been awarded Equitable Growth grants for previous research, demonstrates that minimum wage increases reduce income inequality by driving up earnings at the lower end of the income distribution.36

In 2018, grantees Sylvia Allegretto, Anna Godoy, and Michael Reich, along with Carl Nadler, all of the University of California, Berkeley, used an Equitable Growth grant to examine the impact of minimum wage increases on the food-services industry in six cities. They find robust, statistically significant, and positive effects of minimum wage increases on average earnings, with no significant negative employment effects.37 And in an important 2016 Equitable Growth working paper, Research Advisory Board member and grantee David Howell of the New School, along with co-authors Stephanie Luce and the late Kea Fiedler, argue that the test of “zero job loss” for the success of a minimum wage increase is too narrow, and that any negative impact on employment, while important, must be weighed against the value of earnings increases.38

In a 2020 working paper based on funded research, Krista Ruffini of the University of California, Berkeley, examined the impact of minimum wage reforms on the residents of nursing homes receiving care from low-wage nursing home workers.39 She finds that a significant increase in the minimum wage raises low-skilled nursing home workers’ earnings, reduces worker separations from their employers, and increases the number of new hires who remain a significant amount of time. These gains translate into marked improvements in patient health and safety and indeed, Ruffini finds, save lives. Moreover, firms are able to fully offset higher labor costs with no significant change in profitability. In an accompanying issue brief grounded in her research, she posits several policies that states and the federal government could consider in order to improve the quality of care in eldercare residential settings, including raising the minimum wage and reforming Medicare reimbursement rates.40

And a new 2020 doctoral grant to Jonathan Garita of the University of Texas at Austin supports research analyzing how the labor market absorbs an increase in the minimum wage. Focusing on Costa Rica’s highly binding and relatively more comprehensive minimum wage policy that includes multiple wage floors based on workers’ skill levels, the author will seek to explain how minimum wages shape the earnings distribution and the labor market equilibrium.

Monopsony, wage setting by firms, and other labor market issues

Equitable Growth supports a variety of research aimed at learning more about the factors that influence how firms set wages, including government policies, labor market institutions, and firm characteristics.

In a 2018 paper supported by Equitable Growth, Patrick Kline of the University of California, Berkeley, Neviana Petkova of the U.S. Department of the Treasury, Heidi Williams now at Stanford University, and Owen Zidar of Princeton University used detailed data to understand the degree to which firms’ performances affect wages.41 They wanted to see how workers fare when their employers experience a positive income shock—in this case, the receipt of a valuable patent. Studying tech start-ups, they showed that about 30 percent of companies’ increased earnings from the receipt of valuable patents went to workers in the form of higher wages and that the benefits were concentrated among higher-income workers, which tended to exacerbate wage inequality at the firms.

The rise in market concentration has also led Equitable Growth to focus more on questions of labor market monopsony—the ability of firms, rather than markets, to set wages because of the difficulties workers face in searching for jobs and finding a good employment match. This can be due to employer concentration or other factors. One telling example of monopsony in action comes from the research of T. William Lester of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (now of San José State University), an early Equitable Growth grantee. In work funded by Equitable Growth, he compared the labor markets of San Francisco and the Research Triangle region of North Carolina, and found that in markets with lower labor standards, such as North Carolina, monopsony enables some firms to follow a low-road wage strategy, resulting in a wider range of compensation among firms in different geographic regions of the country.42

A 2020 working paper based on funded research shows that longer-term Unemployment Insurance benefits can improve workers’ labor market outlook by improving the quality of worker-job matches. Looking at the effects of the federal extensions of Unemployment Insurance compensation during the past two recessions, Equitable Growth grantee Adriana Kugler and former Dissertation Scholar Umberto Muratori, both of Georgetown University, and Ammar Farooq, now at Uber Technologies, find that the Unemployment Insurance extensions introduced during the past two recessions increased earnings and enabled workers to work in better firms, compared to their previous jobs.43

In addition, the three scholars conclude that the longer durations of unemployment benefits increased the educational requirements in workers’ new jobs and decreased the mismatch between workers’ educational attainments and the educational requirements of jobs. The effects were greater for women, non-White, and less-educated workers. In an op-ed for The Hill, Kugler argues this is one reason Congress needs to provide additional extended benefits during the current recession.44

New 2020 grants in this area include the following:

Recent research shows that workers in outsourced establishments—such as call centers, janitorial service companies, or security services—receive lower pay and worse benefits than workers doing the same jobs who are employed by lead or primary firms. This is one of the reasons that much of the growth in earnings inequality in the United States may be explained by the growth in inequality across firms or establishments. With the help of an Equitable Growth grant, Lee Tucker and James Spletzer of the U.S. Census Bureau, Johannes Schmieder of Boston University, and David Dorn of the University of Zurich will conduct a study based on rigorous, quantitative analysis of the extent to which domestic outsourcing has contributed to inequality in the United States and whether it has effects beyond income—most critically, on access to employer-provided health insurance.

Steve Viscelli of the University of Pennsylvania will examine the impact on workers—Amazon.com Inc. workers specifically—of new labor practices affecting “last-mile” package delivery. It will focus on new technologies used to manage workers through communication and monitoring, algorithmic planning and management, and the surveillance of delivery by customers. It will seek information on how workers are responding to these technologies in the context of increasing outsourcing. It will provide ethnographic insights into Amazon’s delivery workers, in particular women, workers of color, and immigrants.

Michael Hout and Siwei Cheng of New York University will use data on job postings and resumes provided by a job market analytics firm to better understand how workers’ skills and employer needs are changing in the U.S. labor market. The level of detail on tasks and occupations available in the data will allow the researchers to make distinctions and explore an array of skills in ways that are not possible with government survey data. The authors will focus on the relationship between skills variations within occupations and inequality, worker mobility, and job quality, including with respect to nonstandard work arrangements.

David Autor and Bryan Seegmiller of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Anna Salomons of Utrecht University will use an Equitable Growth grant to construct a database of new work from 1900 to 2020. They will compile a list of job titles from the U.S. Census Bureau in order to chart the evolution of new work across 12 decades and assess the role of new work and technologies in job creation and skill demands over time, and to test a set of economic hypotheses about where and when new work arises.

A climate-related challenge that does not get sufficient attention is the impact of a warming climate on labor markets. For workers whose jobs expose them to the elements—in sectors such as construction and agriculture—temperature stress creates challenges not only for health but also for job performance and other job-related issues such as cognitive performance, labor capacity, and workplace safety. A 2020 grant reflecting Equitable Growth’s interest in the impact of climate change is that awarded to Robert Jisung Park of the University of California, Los Angeles, who will examine the extent to which climate change could exacerbate income inequality by reducing earnings and job quality for many low-skilled workers and suggest possible workplace adaptations and policy reforms.

A recipient of a 2020 doctoral grant, Benjamin Scuderi of the University of California, Berkeley, will explore the problem of setting federal tax policy aimed at encouraging work when U.S. labor markets are imperfectly competitive. Specifically, the researcher will study the current effects of the wage-subsidizing Earned Income Tax Credit in monopsonistic labor markets and what would comprise an ideal design. The research will help determine whether the tax credit’s usefulness for combatting inequality is undermined by the capture of a large portion of the subsidy by employers, to the extent that the credit allows them to pay lower wages.

Another 2020 doctoral grant went to Geoffrey Schnorr of the University of California, Davis, who will study how earnings volatility, among other factors, can affect the “base period” on which the level of Unemployment Insurance is set. Because low-income workers experience significant volatility in earnings, this research can provide evidence for policy measures that help ensure the fairness of jobless benefits for unemployed low-income workers.

The effects of discrimination in the labor market

Equitable Growth also supports a range of work seeking to document the consequences of gender and race discrimination on labor markets and labor market outcomes. For example, an employer who chooses a White job candidate over a Black job candidate even though the Black candidate is more qualified—and would be more productive—is choosing based on racism. This, in an economic sense, is counterproductive.

Equitable Growth seeks to push the boundaries on this research by supporting David Pedulla of Stanford University, who is continuing an important empirical line of research that builds on the innovative field-based experimental methods developed by the late Devah Pager, who was a co-author on this work.45 The research seeks to understand the dynamics of discrimination. Pedulla is combining an unusually large and broad audit study that drills down on data on race and gender with a survey of employers in an effort to provide a more precise assessment of how organizations perpetuate or address discrimination based on gender, race, and parental status.

A 2020 doctoral grant to Janet Xu of Princeton University will support her exploration of the consequences of diversity programs for recipients’ labor market outcomes. Using an audit study, the researcher will examine how Black university diversity scholarship recipients fare when seeking entry-level jobs after graduation, in comparison to other Black job applicants, as well as White applicants who did and did not receive scholarships. She will seek to understand the perceptions of hiring professionals that may explain the differential treatment of diversity scholarship recipients. The study could add to our understanding of whether diversity initiatives inadvertently stigmatize recipients.

Along this line of research, Equitable Growth 2016 grantees Joya Misra of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and Marta Murray-Close of the U.S. Census Bureau, along with their co-author Eunjung Jee, also of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, demonstrate the persistence of the “motherhood penalty,” or the reduced career wages received by mothers compared to childless women.46 They examined periods between 1986 and 2014, and found that it essentially did not change—while the gross pay gap between childless women and mothers of two or more children narrowed, this was mainly because mothers invested more in their human capital (education and workforce experience, for example), not because of an actual reduction in the motherhood penalty. For mothers of one child, the gap may have increased slightly.

Based on these results, the authors conclude that market forces alone will not fully eliminate the motherhood penalty and that doing so will also require policy changes aimed at supporting parents’ employment, such as child care or paid family and medical leave. Given the importance of two incomes for most U.S. households, this kind of research can help policymakers sort out how to prevent gender and race discrimination in U.S. workplaces.

Nancy Folbre of the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Kristin Smith of the University of New Hampshire (now of Dartmouth College), with support from Equitable Growth, are studying this dynamic by furthering policymakers’ understanding of wages in care industries—health, education, and social services. Their research shows that managers and professionals employed in these industries, where many employers are in the public sector or are private nonprofits, receive significantly lower compensation than those with comparable education and training in other industries.47 They offer a number of reasons, including possible gender discrimination and the lower value placed in labor markets on stereotypically feminine work capabilities.

Another good example of the impact of policy and structural power in determining economic outcomes is provided in a 2020 working paper by Ellora Derenoncourt, then of Princeton University (now of the University of California, Berkeley), with co-author Claire Montialoux, also at UC Berkeley.48 Derenoncourt and Montialoux find that that the 1966 extension of the minimum wage to previously exempt industries, such as agriculture, nursing homes, and restaurants—where Black workers are significantly overrepresented—was responsible for about 20 percent of the decline in the Black-White earnings divide in the United States that occurred in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In a New York Times op-ed, the authors argue that raising minimum wages at the federal, state, and local levels could help reduce racial earnings inequality today as well.49

Relatedly, a 2020 working paper by Abhay Aneja of the University of California, Berkeley and Carlos Fernando Avenancio-León of Indiana University Bloomington finds that the enactment of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a landmark civil rights law that led to a dramatic expansion of voting rights for people of color, especially in the South, also contributed significantly to the decline in the earnings difference between Black and White workers.50 The authors attribute the improvement in Black workers’ relative position to increased public employment, fiscal redistribution, and implementation and enforcement of policies such as affirmative action and anti-discrimination laws. In an accompanying issue brief, the authors suggest that a revitalized Voting Rights Act, including its stringent enforcement measures, may still be vital to establishing full economic equality for Black voters and other voters of color.51

And Jose Joaquín Lopez and Jamein Cunningham of the University of Memphis have been awarded a 2020 grant to study the evolution of and relationship between U.S. civil rights enforcement and the labor market outcomes and intergenerational mobility of people of color. Their work will address a lack of empirical evidence in the degree to which the private enforcement of anti-discrimination legislation through the federal courts has influenced racial divides in earnings and other socioeconomic outcomes. The authors will also create a comprehensive dataset on the political party composition of judges across courts and over time to examine how presidential appointees have influenced the evolution of civil rights enforcement.

Worker power and the future of labor unions

Worker power and the future of labor unions are key elements of how wages are set. W. Bentley MacLeod and Suresh Naidu of Columbia University and Elliott Ash of the University of Warwick (now of ETH Zurich) used an Equitable Growth grant to document determinants of control rights in union contracts using a new corpus of 30,000 collective bargaining agreements in Canada from 1986 through 2015.52 Employing ideas and methods from computational linguistics, they measured the level of worker control and analyzed variation in contracts according to firm-level and external factors. They find that collective bargaining agreements set up obligations for employment for both the workers and the employers, yet offer entitlements, in the form of better working conditions, only to employees. In turn, these positive working conditions reduce the likelihood of labor conflict.

Economists generally agree that economic inequality tends to decline with higher rates of union membership and rise with lower union density, an understanding in need of further evidence, given the breadth of legal barriers and firms’ resistance to unionization. Another Naidu paper, authored in conjunction with Henry Farber, Ilyana Kuziemko, and Daniel Herbst, all of Princeton University, shows an explicit relationship. Their paper suggests that rates of union membership have a direct impact on income distribution.53

In addition, motivated in part by the long-term decline in labor union membership in the United States, Alex Hertel-Fernandez is exploring, with his colleagues William Kimball and Thomas Kochan of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, what services workers would want unions to provide if U.S. labor laws and traditional labor practices could be re-examined.54

Equitable Growth sustains its work on these issues with new research grants in the 2020 cycle. Suresh Naidu and Adam Reich of Columbia University and Ruth Milkman and Luke Elliott-Negri of the City University of New York received a grant to assess worker power—including the impact of customer interest and actions—in food-related industries, including processing facilities, grocery stores, restaurants, and platform-based food delivery services. In light of the coronavirus pandemic, they will examine the effects of different aspects of job quality, including safety issues, on the likelihood of workers to leave a current job. They will consider the role customers play as a source of power for U.S. workers who strike or protest working conditions, surveying the public to assess changing food consumption habits, as well as perceptions of food workers and collective action during the pandemic.

Equitable Growth has also awarded a 2020 doctoral grant to Glen Kwende of American University, who seeks to estimate changes in workers’ bargaining power over time in the United States to determine its role in the lack of adequate wage growth in the pre-recession tight labor market. His work will make important extensions on the job search model and then look at the role of worker bargaining power in labor market dynamics such as vacancies and unemployment.

Figure 4 below captures the range of our work on the issue of the minimum wage, a key part of our academic grantmaking and policy analysis of the U.S. labor market.

Equitable Growth’s 2021 Request for Proposals on the labor market

Our core questions of interest in the labor market channel are:

The labor market

How does inequality affect the labor market? How does the labor market and workplace organization affect whether growth is broadly shared? What are the labor market impacts on intergenerational mobility, and have changes in employer-employee relationships and new types of work arrangements affected the opportunity for job advancement and mobility? How prevalent is discrimination in the labor market, and what are its effects? What role does technology play in the organization of and returns to work?

Areas of interest include but are not limited to:

Power in labor markets

What is the relative bargaining power of workers versus employers, what influences that balance, and how does it affect pay levels, job quality, and economic growth? Do structural barriers, including structural racism, or social norms affect labor market dynamics? What role do public policies, unions, and other forms of workplace organization play in determining labor market power? What effect do new technologies and new types of work arrangements have on who has power and how that power is exerted?

Workplace organization

How are labor market institutions succeeding or failing in the face of new forms of workplace organization, including those driven by the adoption of new technologies? How prevalent are nontraditional work arrangements, and what are their implications for earnings levels and volatility, economic mobility, tenure and job security, access to benefits, and legal protections under the law? Do those effects differ for different demographic groups? How does enforcement of existing labor laws affect outcomes?

Returns to work

What factors affect how economywide growth is or is not shared between different types of workers? What role does structural racism play, and what policies may be effective in decreasing the racial wage gap? To what degree do aggregate productivity changes pass through to individuals and via which mechanisms? How is inequality shaping the relationship between nonmarket and market work and individuals’ decisions on how to divide their time between the two?

Academic letters of inquiry are due by 11:59 p.m. EST on February 7, 2021.

If invited, full proposals will be due by 11:59 p.m. EDT on May 9, 2021.

Dissertation Scholars program applications are due by 11:59 p.m. EST on February 7, 2021.

Doctoral/postdoctoral proposals are due by 11:59 p.m. EDT on March 28, 2021.

Funding decisions will be announced by July 2021. We anticipate that funds will be distributed in early fall 2021, though the timing of disbursement depends in part on the particulars of the project and the researcher’s home institution.

Market structure

Equitable Growth initially directed significant attention to entrepreneurship and innovation as a funding channel for its grantmaking because both are essential to economic growth. After several years, however, we revised this area to focus on market structure because of the increasing evidence—some of it from research we supported—showing that increasing market power is distorting markets and reducing innovation, as well as undermining entrepreneurship.55

Moreover, the accumulating evidence that market power is having an impact on labor markets prompted us to support research to understand whether and how these trends are affected by and contribute to economic inequality. We are now asking researchers to examine:

- The existence and causes of increased market power

- The consequences of market power for product markets, new business formation, firm growth, business investment, productivity, labor markets, and worker power

- The effectiveness of policy tools

Let’s look at each of these grantmaking issue areas in turn.

The existence and causes of increased market power

In “Kaldor and Piketty’s facts: The rise of monopoly power in the United States,” co-authors Gauti Eggertsson, Equitable Growth 2017 Dissertation Scholar Jacob A. Robbins, and Ella Getz Wold, all at that time of Brown University, examined five puzzling trends over the past 40 years involving economic growth and rising inequality:

- Financial wealth has increased relative to investment.

- The financial value of many firms now is permanently higher than the cost of their assets.

- Investment has fallen relative to output despite higher profits and low interest rates.

- The average rate of return on capital has stayed steady while interest rates have dropped.

- The share of income going to labor has declined as the share of income going to profits has increased.56

The authors concluded that the new facts can be explained by an increase in market power, caused by declining competition and increased concentration, and a decline in the “natural” interest rate.

Nathan Miller of Georgetown University will use a 2020 Equitable Growth grant to study increased concentration through an industry-specific analysis, common in the industrial organization literature, as opposed to the macroeconomic approach taken by 2016 Equitable Growth grantee Gauti Eggertsson and his co-authors. By analyzing data over the past several decades in the cement industry, Miller will explore how the technological change sparked by the introduction of the precalciner kiln altered market structure and the share of income going to owners’ profits relative to workers’ wages over time. This industry-specific analysis can help lead to broader conclusions about the advance of market power.

The consequences of market power for product markets, new business formation, firm growth, business investment, productivity, labor markets, and worker power

In 2017, we provided an Equitable Growth doctoral grant to Brian Callaci, then a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and now a postdoctoral scholar at the Data & Society Research Institute. He shows how the franchising business model gives fast-food and other large companies the ability to effectively integrate their operations vertically but avoid antitrust prohibitions on such arrangements.57 Franchised chains replace formal ownership and employment with contractual mechanisms that enable franchisers to exercise control over prices and suppliers, and avoid having to bargain collectively with thousands of low-wage workers.

Moreover, Callaci finds that most franchisors impose noncompete agreements on franchisees, which prevent the latter from using the human and physical capital they have accumulated in the franchised business in alternative employment once the contract ends.

In 2019, Equitable Growth announced several new grants in the area of market structure. David Berger of Duke University, Kyle Herkenhoff of the University of Minnesota, and Simon Mongey of the University of Chicago are studying the extent to which corporate mergers might have a monopsonistic effect on competition in the U.S. labor market.58 They are looking at the effects on compensation and numbers of jobs for low- and high-wage workers and more broadly at labor’s share of business income. They are also studying long-term effects on earnings for those who lose their jobs in the wake of a merger.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Simon Jäger and Benjamin Schoefer of the University of California, Berkeley are studying the impact of shared corporate governance—workers participating in the management of the companies where they work.59 This is not so common in the United States but is the law in some other countries, including Germany. Their project uses reforms in the German law to analyze the effects of shared governance on such outcomes as wages, distribution of profits, and pay equity within firms.

Examining a more specific market, Randall Akee of the University of California, Los Angeles and Elton Mykerezi of the University of Minnesota have extended their prior work (alongside Richard M. Todd at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis) studying business dynamics on and near American Indian reservations.60 With a 2019 grant from Equitable Growth, Akee and Mykerezi are focusing on how large casinos acting as anchor businesses affect the transportation, food services, retail operations, and lodging industries.61 The research will not only produce new data on American Indian reservations, which is severely lacking, but also shed light on what economic development policies might be successful in isolated, rural areas.

A new 2020 doctoral grant to Lena Song will help her to explore the impact of new market competition on the racial divide. Specifically, the researcher will look at how the entry of television into local markets in the 1950s and 1960s affected programming for Black audiences. This historical analysis will focus on whether racial discrimination by firms led to underprovision of content for minorities in the U.S. radio market in the post-war Jim Crow era and whether that pernicious effect was eased by the introduction of greater competition.

Effectiveness of policy tools

We are interested in empirical work that examines the effectiveness of policies to promote competition, including, but not limited to, the state of antitrust enforcement and regulatory approaches. We are also interested in the production of new data to study these issues, since few data sources exist.

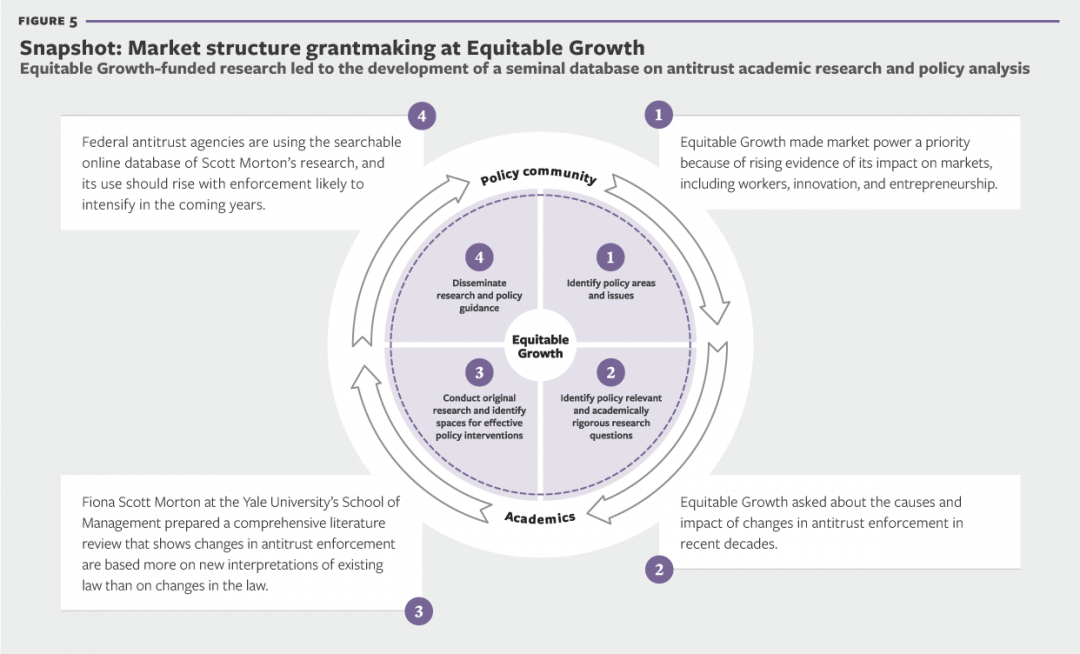

We provided a 2018 grant to Fiona Scott Morton of the Yale University School of Management to help fill the data gap.62 Scott Morton is collecting empirical metrics of merger outcomes in order to analyze effects beyond prices, taking into consideration other factors such as employment, innovation, and efficiencies. Information will be collected before and after a merger. Data will then be compared to the outcomes predicted by the merging firms.

A second component of Scott Morton’s research will examine the purposes and outcomes of acquisitions in the high-tech sector to determine whether acquisitions are motivated by increased efficiencies or by the elimination of competitors, a question that is largely unexplored. This line of inquiry seeks to test whether recent acquisitions have stifled innovation.

As part of the grant, Scott Morton prepared a comprehensive literature review that provides policymakers, antitrust enforcers, and the courts with up-to-date research on the impact of changes in antitrust enforcement over the past several decades, which she suggests are based more on new interpretations of existing law than on changes in the law.63 She will update this literature review as new research emerges.

Similarly, 2019 grantees Simcha Barkai of Boston College and Ezra Karger of the University of Chicago are constructing a comprehensive database of more than 125 years of U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission antitrust enforcement actions—from 1890 to 2017.64 They will then link these data, which include actions against firms and individuals, to other government data to measure the effect of antitrust enforcement on economic output.

A new 2020 grant to Vivek Bhattacharya and Gaston Illanes of Northwestern University will support them to create a comprehensive retrospective of the effects of past mergers on prices. This will enable comparisons with the outcomes that were predicted by antitrust enforcers as they considered whether to permit those mergers, and the authors will attempt to uncover the causes of any prediction errors. Since such simulations are a critical part of the regulatory process, this ambitious project could provide a wealth of information about consummated mergers and the predictive power of merger simulation techniques, contributing to the infrastructure used to regulate competition.

A related 2020 grant to Federico Huneeus of Yale University, Thomas Wollmann of the University of Chicago, and José Ignacio Cuesta of Stanford University will support the authors to carry out a project that estimates the impact of prospective merger reviews on antitrust enforcement actions, product prices, input prices, output, investment, and research and development. The study will determine how the introduction of a premerger notification policy in Chile changed the types of mergers being agreed to. The results will help policymakers understand any deterrent impact of notification systems. This comprehensive study across industries could provide valuable insights into the effects of mergers, the impact of notification requirements, and the considerable resources enforcement agencies allocate to the process.

The University of Washington’s Michele Cadigan will explore the potential interplay of government-granted market power and equity with a 2020 doctoral grant for her study on the market for recreational cannabis in the wake of legalization initiatives in Seattle, Boston, and San Francisco. Since the war on drugs disproportionately incarcerates members of the Black and Latinx communities, this study will provide a unique look at the effects of a market change brought about by government and show how criminal justice and racial economic equity initiatives can align.

See Figure 5 for an emblematic breakdown of how Equitable Growth’s recent grant-giving in the market structure arena is boosting academic data gathering while also informing antitrust and competition policymakers.

Equitable Growth’s 2021 Request for Proposals on market structure

Our core questions of interest in the market structure channel are:

Market structure

What is the role of market structure in determining economic growth and its distribution? What is the relationship between inequality, market power, and economic growth? How competitive are markets in the U.S. economy, and is that changing? What conduct is likely or unlikely to harm competition and how? Equitable Growth is interested in research from an aggregate perspective, which has been common in the macroeconomic and labor literatures, as well as industry- or market-specific analysis that has been the focus of industrial organization literatures.

Areas of interest include but are not limited to:

Existence and causes of market power

Is there increased market power in the economy, and if so, what are its causes? Areas of interest include studies of mergers, potential competition, and specific conduct. Is anticompetitive activity more common in some industries than others?

Consequences of market power

What are the effects of market power on product markets, labor markets, and small business, including new business formation, firm growth, business investment, productivity, and inequality? How have technological developments affected competition? How does market concentration affect the development or deployment of new technologies to mitigate climate change and support sustainable economic growth? Does market power disproportionately affect historically marginalized groups? How do racial and other inequalities affect competition?

Effectiveness of policy tools

Equitable Growth is particularly interested in empirical work that examines the effectiveness of policies to promote competition, including, but not limited to, the state of antitrust enforcement, regulatory approaches, new foundations for antitrust actions that do not necessarily rely on prices, and comparisons of the U.S. antitrust enforcement regime with other models. Equitable Growth also is interested in the differential effect of policies on different sized firms, particularly small business and minority-owned business, and the ways in which policies are shaping markets.

Academic letters of inquiry are due by 11:59 p.m. EST on February 7, 2021.

If invited, full proposals will be due by 11:59 p.m. EDT on May 9, 2021.

Dissertation Scholars program applications are due by 11:59 p.m. EST on February 7, 2021.

Doctoral/postdoctoral proposals are due by 11:59 p.m. EDT on March 28, 2021.

Funding decisions will be announced by July 2021. We anticipate that funds will be distributed in early fall 2021, though the timing of disbursement depends in part on the particulars of the project and the researcher’s home institution.

Conclusion

This is our first promised update of the comprehensive report we issued 1 year ago, summarizing the results of 7 years of grantmaking, as well as providing hints of future research results. We are very excited that our research, more than ever, is providing the evidence for potential new policies that can foster strong, stable, and broad-based economic growth. We expect research funded by Equitable Growth to continue to play an outsized role in advancing our understanding of the sources of economic inequality and of how the economy grows.

A critical part of our mission is advanced by our engagement with Equitable Growth’s ever-growing academic network. With more than 200 grantees, as well as our distinguished Steering Committee and Research Advisory Board, we expect to be an even greater source of knowledge and evidence about these critical issues for policymakers, the media, and the public. We engage with scholars up and down the career ladder through our grant program, as well as through conferences and other meetings (mainly virtual in 2020), and we elevate their research for both academic and policy audiences.

In these ways and through direct engagement with policymakers and the media about the research we fund, Equitable Growth’s team in Washington bridges the gap between academia and policy. Please go to the “Elevating Research” page on our website and explore the ways you can connect with our network or take advantage of the support we offer.65

And please be sure to check our 2021 Requests for Proposals as the deadline for academic letters of inquiry is February 7, 2021.66 The deadline for doctoral and postdoctoral proposals is March 28, 2021. Due to the generosity of our funders, we have been able to increase the amount of funding available in each successive grant cycle since 2014, enabling us to develop further evidence on the effects of inequality on equitable growth for policymakers. We look forward to your applications.

End Notes

1. Washington Center for Equitable Growth, “Statement on structural racism and economic inequality in the United States,” June 4, 2020, available at https://equitablegrowth.org/press/statement-on-structural-racism-and-economic-inequality-in-the-united-states/.

2. Washington Center for Equitable Growth, “Equitable Growth awards more than $250,000 for new research on paid leave,” Press release, July 22, 2020, available at https://equitablegrowth.org/press/equitable-growth-awards-more-than-250000-for-new-research-on-paid-leave/.

3. “Request for Proposals 2021: Overview,” available at https://equitablegrowth.org/research-paper/2021-request-for-proposals/ (last accessed January 26, 2021).

4. Washington Center for Equitable Growth, “Inequality and economic growth” (2019), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/research-paper/inequality-and-economic-growth/.

5. Monica Garcia-Perez, Sarah Elizabeth Gaither, and William Darity Jr., “Baltimore Study: Credit Scores.” Working Paper (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/working-papers/baltimore-study-credit-scores/.

6. Christina Patterson, “The Matching Multiplier and the Amplification of Recessions.” Working Paper (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/working-papers/the-matching-multiplier-and-the-ampli%ef%ac%81cation-of-recessions/.

7. Jonathan Fisher and others, “Inequality in 3D: Income, consumption, and wealth.” Working Paper (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2016), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/working-papers/inequality-3d-income-consumption-wealth/.

8. “World Inequality Report, 2018,” available at https://wir2018.wid.world/ (last accessed January 26, 2021).