Voting rights equal economic progress: The Voting Rights Act and U.S. economic inequality

Overview

The civil rights movement, from its mid-20th century growth and successes to its current manifestations, has had a dual focus of eliminating political and social discrimination and bettering the economic lot of Black Americans, as well as that of other people of color in the United States. From the beginning, leaders of the movement and their political allies recognized the intrinsic connection between these goals. They understood that equality under the law meant little without addressing the rampant poverty in Black communities across the country.

Our new research quantifies that direct connection, showing that the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a signature measure of the civil rights era, narrowed the wage gap between Black and White men in the areas where it was most strictly enforced. Specifically, between 1950 and 1980, the gap between the median wages of Black and White workers in the South narrowed by approximately 30 percentage points. And our study, which builds on existing research on the economic benefits of voting rights legislation, shows that the Voting Rights Act was responsible for about one-fifth of that reduction.

This issue brief first details why the Voting Rights Act delivered greater political power to Black voters. We then show that this resulted in higher wages to Black workers and narrowed the Black-White wage gap. We examine some ways the Voting Rights Act could have had this wage effect, specifically developments in public- and private-sector employment and greater enforcement of measures barring discrimination in the workplace. We close with a brief look at how the U.S. Supreme Court decision in 2013 to dramatically weaken enforcement of voting rights may be starting to reverse the wage gains we document after the enactment of the Voting Right Act.

The Voting Rights Act

No civil right was considered more important by civil rights proponents than the right to vote, which had been systematically denied to Black people for decades, primarily in the South. Following the Civil War, the ratification of the 15th Amendment to the Constitution in 1870 enshrined voting rights for American men regardless of race. And during Reconstruction, Black Americans generally prospered economically. But beginning near the end of the 19th century, Jim Crow laws in the South gradually and systematically deprived Black Americans of the right to vote in many areas. By 1910, there was very limited Black suffrage in the South, and that remained the case for more than half a century.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 changed that. It not only outlawed the standard practices used to deny Black Americans the right to vote, such as the poll tax and literacy tests, but also contained very tough enforcement measures. The new law gave the federal government extraordinary oversight powers to protect the voting rights of people of color in specific counties through much of the South. Any changes in electoral procedures needed to be cleared with the U.S. Department of Justice or the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia before going into effect, and the Justice Department was authorized to appoint federal examiners to oversee the electoral process in covered jurisdictions to ensure that roadblocks were not placed in the way of Black voters.

The results were dramatic. The size of the Black electorate increased almost overnight. Within 2 years, more Black Americans had registered to vote than at any point since the ratification of the 15th Amendment.

To calculate the effect of the Voting Rights Act on wages, we were able to compare counties that were covered by the stricter Voting Rights Act provisions to those that were not. Only 41 of 100 counties in North Carolina, for example, were covered by the stricter provisions, so neighbor counties can be compared. All of Mississippi was covered, but Arkansas next door was not. In addition, subsequent amendments to the Voting Rights Act added more counties in the South and Southwest, providing additional opportunities for comparisons, not only with newly adjacent uncovered counties but also with the counties that had been covered 5 and 10 years earlier.

How the Voting Rights Act changed politics

In order for the Voting Rights Act to improve the well-being of Black Americans, it had to make government more accountable to Black voters. If improvements were a response to their greater electoral strength, then the first question was how the law affected the demographic makeup of the electorate. So, we first examined voter turnout between 1948 and 1980, and found increases in overall eligible voter turnout for all voters of anywhere from around 6 percent to 10 percent, consistent with existing research in this area.

Moreover, there also was increased White voter registration during the period, but the statute produced much larger increases in Black voter registration. Finally, our research builds on existing research by showing specifically that in jurisdictions where federal examiners monitored the voting process, political participation showed the greatest increases.

As might be expected, elected officials began responding to the increased Black vote. Using data on the behavior of members of Congress from the covered jurisdictions, we found that these elected officials increasingly supported the preferred policies of their Black constituents, specifically on issues directly related to race and civil rights. This finding is consistent with research from political science on the Voting Rights Act.

Impact of the Voting Rights Act on racial earnings inequality

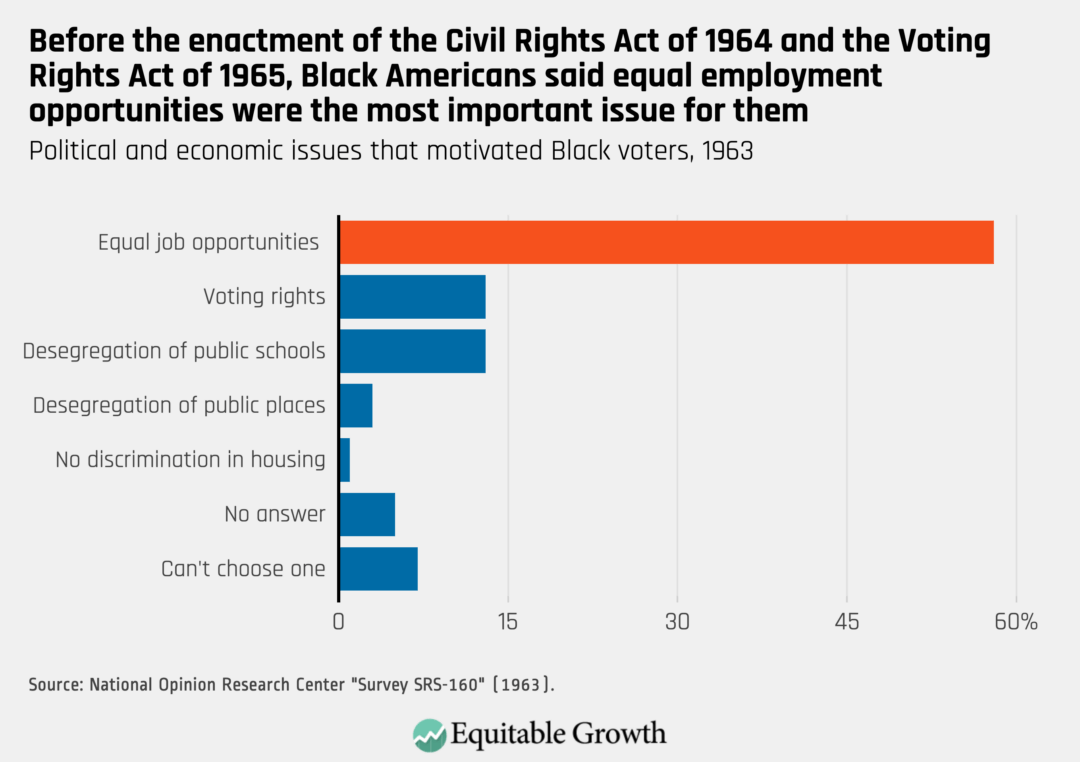

Eliminating U.S. labor market discrimination was by far the most important political issue for Black Americans before the enactment of the civil rights legislation of the 1960s. It should be no surprise, then, that once Black Americans gained greater political power, it would be directed like a laser beam toward that issue. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

In our new working paper, we analyzed U.S. Census Bureau data in adjacent jurisdictions, as noted above, to estimate the specific impact of the Voting Rights Act on the gap in earnings between Black and White men. The results were clear: a 5.5 percentage point increase in Black Americans’ wages between 1950 and 1980, relative to White workers with the same characteristics and within the same geographic area.

Between 1950 and 1980, the ratio of wages for Black workers to wages for White workers increased from 55 percent to just more than 80 percent. Since the main impact of the Voting Rights Act in narrowing the Black-White wage gap 5.5 percent took place in the 5 years following its enactment, between 1965 and 1970, the measure is responsible for about one-fifth of the total convergence between Black and White wages.

We also found that the narrowing of this divide was driven primarily by a substantial increase in earnings among Black workers. Yet there was no loss of employment for Black or White workers. Employers did not hire fewer workers because wages rose, perhaps due to the favorable economic conditions of the time.

If the Voting Rights Act is responsible for one-fifth of this phenomenon, what makes up the rest? Other researchers have quantified several other factors, including the migration of Black workers to the North during the period of the Great Migration, improvements in school quality for Black American schoolchildren, and the effect of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs on U.S. labor force participation, caused, in part, by the increased bargaining power the support provided to Black workers.

A third source of the increase in wages among Black workers was detailed recently by economists Ellora Derenoncourt and Claire Montialoux at the University of California, Berkeley. They find that the 1966 National Labor Relations Act reforms that broadened the federal minimum wage to cover previously exempt industries, including nursing homes, hotels, and agriculture, explains more than 20 percent of the earnings gap reduction. Of course, people of color’s political power may have complemented any of these channels by strengthening enforcement of these laws.

We examined a number of factors that could have made interpretation of our analysis challenging. We tracked Black migration from one county or state to another, the integration of labor markets across county or state borders, and workers commuting from one jurisdiction to another. Using these additional data, we were able to essentially rule out that any of these factors had a significant effect on our research.

What were the means by which the Voting Rights Act affected earnings?

Now that we know that the Voting Rights Act narrowed the Black-White wage gap, the natural question is, how? What are the channels by which this landmark measure effected economic progress for Black workers in the decade-and-a-half following its enactment? We looked at a few possible channels, including:

- Increased Black employment in the public sector

- Anti-discrimination and affirmative action policies implemented at all levels of government

- Changes in human capital, such as improved education and health, leading to workers more capable of earning higher wages

Let’s examine each of these in turn.

Public-sector employment

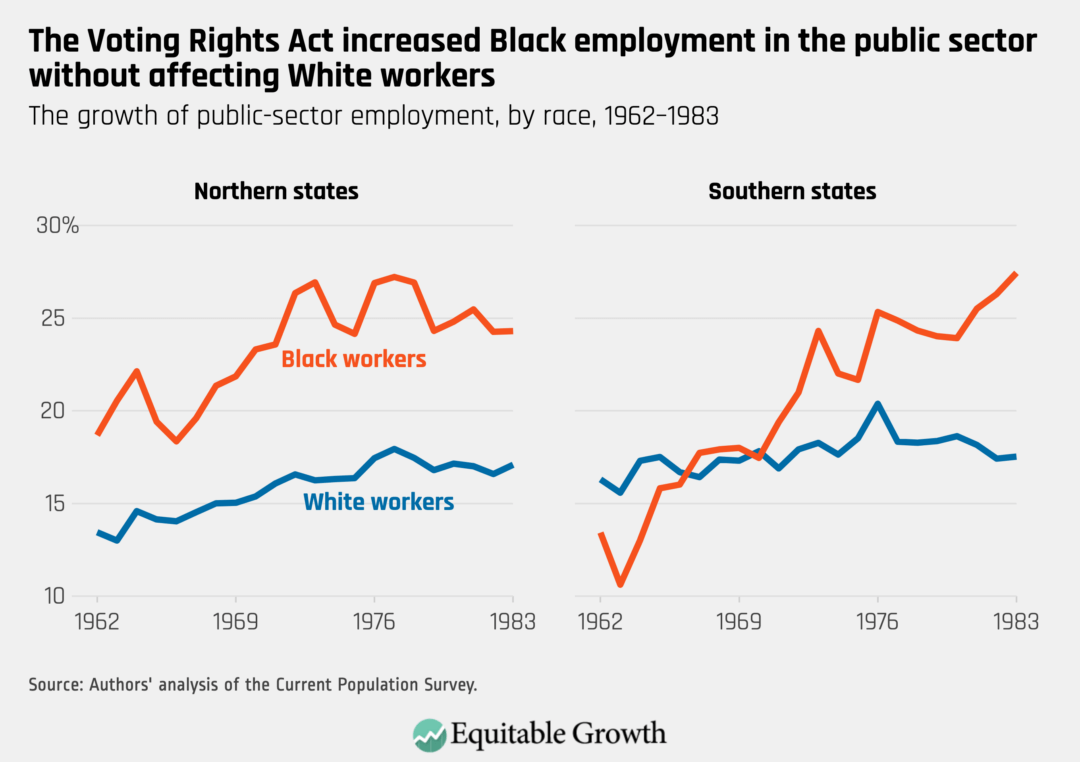

Previous research suggests that greater diversity among government workers is one effect of increased political power for people of color. We calculate that of the approximately 5 percent narrowing of the racial wage divide in Voting Rights Act jurisdictions between 1950 and 1980, at least one-tenth of that convergence was achieved as a result of greater public employment, including its spillover effect on the private sector. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Public employment provided a premium, especially to Black workers, over private employment. Wages in the public sector were higher in general, and there was greater discrimination in terms of hiring, pay, and position in the private sector. Black workers had greater opportunities in the public sector than in private employment to move to higher-paying, white-collar positions.

In addition, this increase was made easier by the concurrent growth of government employment occurring in much of the country. That overall growth meant that the growth of Black employment, which occurred at a higher rate in the jurisdictions covered by the Voting Rights Act, could be achieved without displacing current White workers. We also find, though, that Black workers’ improved circumstances in the public sector had a spillover effect, contributing to the narrowing of the racial wage gap in the private sector. Faced with the higher wages paid by government agencies, private employers likely had to offer more competitive pay to attract workers.

Direct government actions

During the 1960s and beyond, a number of federal, state, and local measures were adopted to improve the economic well-being of Black Americans and other people of color. Two of the most important at the federal level were Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited employment discrimination based on “race, color, religion, sex, or national origin,” and a series of executive actions through several administrations requiring affirmative action to prevent employment discrimination or specifically encourage hiring workers of color. There also was a nationwide increase in the minimum wage. In addition, some local governments took their own actions to encourage hiring and contracting people of color.

Government reporting requirements under Title VII applied only to firms above a set number of employees. Localities thus varied in the fraction of workers employed in establishments subject to these oversight requirements. We found that the Voting Rights Act’s effect on relative earnings was (differentially) more in places where a greater fraction of the private-sector workforce was likely to be subject to these reporting requirements. We believe this may suggest that another mechanism through which political power mattered was through improved Title VII enforcement.

Changes in human capital

Finally, there is no question that expanding the franchise in the United States led to increases in spending on education and health, adding to workers’ human capital. But it turns out these improvements in human capital did not play a significant role in the wage-gap narrowing that we are discussing. Among other reasons, the impact of increased spending was felt later than the narrowing of the wage gap we are discussing.

Unlike the other channels above, the data here do not help us draw a line from the Voting Rights Act to changes in human capital to the narrowing of the Black-White earnings gap. Rather, the clear improvements in school quality for Black children fostered by the Voting Rights Act seem to have occurred in tandem with the improvements in adult outcomes that we document in our paper.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, stringent federal enforcement of voting rights for people of color in the South and other areas covered by the Voting Rights Act is a historical relic. In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Shelby County v. Holder, invalidated the provision of the Voting Rights Act that authorized the Justice Department to send enforcers to those counties that had a strong history of discrimination against Black voters and other voters of color. While Chief Justice John Roberts claimed that voting equality had been achieved, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg argued that if voting equality existed in 2013, it may have been precisely because of the “prophylactic measures to prevent purposeful race discrimination” taken under the Voting Rights Act.

The impact of Shelby County v. Holder on the voting rights of Americans of color is about as controversial a political issue as there is right now in the South and Southwest. And in separate research, we find that the removal of these protections has had a negative economic impact on Black workers, though modest so far, yet consistent with the economic improvements in the 20th century that were attributable to Voting Rights Act enforcement. That impact has been felt largely due to reversals in the same channel where improvements took place half a century ago: public-sector employment, with spillovers into the private sector.

The Voting Rights Act, now hobbled, turned 55 in August 2020. The economic effects of Shelby County v. Holder, which are undoubtedly related to the successful efforts by some governors and state legislatures to reduce voter registration and turnout among people of color, suggest that a revitalized Voting Rights Act, including its stringent enforcement measures, may still be vital to establishing full economic equality for Black voters and other voters of color. As the nation continues to struggle with how to achieve economic justice, voting rights, as in the 1960s, are still front and center.

—Abhay P. Aneja is an assistant professor of law at the University of California, Berkeley, and Carlos Fernando Avenancio-León is an assistant professor of finance at the Kelley School of Business, Indiana University Bloomington.