A research update

Fast facts

- Building on prior research, some new studies demonstrate that there is a relationship between high levels of inequality and low levels of absolute mobility, or a child’s economic well-being compared to their parents’ economic well-being at a similar point in the life cycle.

- New methodological innovations have engendered a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships between inequality and mobility. For instance, examining racial inequality, the University of California, Los Angeles’ Randall Akee and his colleagues use unique linked data to demonstrate the persistence of a calcified income structure in which Black, American Indian, and Hispanic individuals are persistently clustered at the lower end of the income distribution, while White and Asian Americans tend to be on the higher end. 1

- This report continues to explore the ways inequality affects mobility through the development of human potential by updating research pertaining to health, parental investments of money and time in children, and in the quality of education. In some of these areas, there is cause for optimism. Parental time gaps, for example, appear to have narrowed such that low- and high-income parents now spend more similar numbers of hours with their children on a weekly basis than they did in decades past. But other developments, such as unequal access to flexible work arrangements such as working from home, which is primarily available to high-income parents, may undo some of this progress.

- This report adds a new dimension, social capital, which explores how social connectedness and integration among socioeconomic classes may improve relative mobility, or a child’s rank in the economic distribution compared to the child’s parents’ place in the distribution at a similar point in the life cycle.

- Regarding the deployment of human potential, this report highlights several new research and political economic developments. A tight U.S. labor market and renewed labor organizing are boosting workers’ wages and worker power, but threats to reproductive rights are threatening women’s labor force participation and incomes.

Introduction

Critical to the promise of the American dream is the expectation of intergenerational mobility. Invoked in ubiquitous phrases such as “pulling oneself up by the bootstraps,” “rags to riches,” and “self-made,” an enduring U.S. economic story is that if someone works hard enough throughout their educational and professional careers, they can reasonably expect to be better off than their parents. What’s more, this idea—that individuals can control their economic destinies through dint of hard work and by taking advantage of opportunities presented to them—has traditionally informed approaches to economic mobility by many policymakers and researchers alike.

In recent years, however, mounting evidence calls these approaches into question on empirical and policy grounds, underscoring the need for a different framework. In 2018, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth highlighted a different framework, publishing its report, “Are today’s inequalities limiting tomorrow’s opportunities?,” to review the landscape of research on economic mobility and illuminate relevant literature, as well as further areas of exploration.

In the report, Elisabeth Jacobs (now at the Urban Institute) and Liz Hipple (now at the U.S. congressional Joint Economic Committee) demonstrate that high levels of inequality tend to be associated with low levels of economic mobility, and they identify two major channels to make sense of this correlation: the development of human potential and the deployment of human potential. The first channel focuses on the role of resources during childhood that can help with acquiring and cultivating human capital. In this section of their report, the co-authors look at factors such as health, parental allocation of time and money, and education. The second channel focuses on the structural factors that can enable or hinder individuals from utilizing their potential. The co-authors identify three major structural factors in this section of their report, including changes to labor market, persistent discrimination, and the longstanding impacts of parental balance sheets.2

Since the publication of Equitable Growth’s 2018 report, new research and new political economic circumstances continue to shed light on mobility, providing depth to the framework outlined above. For instance, developments in research since 2018 continue to confirm the importance of the deployment channel, linking intergenerational mobility to structural factors such as racial and gender inequities. The COVID-19 recession in 2020 and subsequent recovery also revealed important pathways related to human potential and economic outcomes, including care policies, access to Unemployment Insurance and other income supports, and the effects of the U.S. wage distribution.

The purpose of this report is to provide an update on the state of mobility research. It will not go into details regarding context for definitions and metrics; section two of the 2018 report provides this context, which remains relevant for this report. To avoid confusion, all designations used in the following research, including racial and ethnic groups, reflect the exact designations used in the research and survey data itself.3

In what follows, this report summarizes relevant research findings from the 2018 report and then highlights new research to help further our understanding of intergenerational mobility in the United States. We use a parallel structure to the 2018 report, looking first at the development of human potential channel and then at the deployment of human potential channel.

But first, we turn to a summary of the 2018 report findings and how the research landscape since then has changed to improve our understanding of mobility in the United States.

Does high inequality today mean low mobility tomorrow?

In our 2018 report, we shared research on how economic inequality impedes opportunity, making it very difficult for hard-working individuals and families to thrive and experience upward mobility in the United States.

One such study was City University of New York economist Miles Corak’s 2013 research on the relationships between economic inequality and intergenerational mobility. Corak looks at children born in the 1960s and their adult outcomes in the 1990s across the world’s advanced economies and finds that countries with low income inequality (measured by the Gini coefficient for disposable household incomes) have higher rates of economic mobility (measured by intergenerational earnings elasticity, or the stickiness of the relationship between a parent and their child’s incomes).4 The Great Gatsby Curve, a term coined by the late Princeton University economist Alan Krueger, describes the high inequality/low mobility relationship.

Similarly, when Harvard University economist Raj Chetty and his team decomposed the contribution of inequality and growth to decreasing intergenerational mobility in the United States, they found that about two-thirds of the decline between 1950 and 1980 is attributable to the highly unequal distribution of growth experienced by later cohorts.5

There are still gaps, however, in our understand of how inequality and mobility are related. The work of Harvard University sociologist Deirdre Bloome reveals that there is little relationship between the two across U.S. states, suggesting that national factors are important.6 Bloome’s work points to gaps in knowledge about the mechanisms that link rising inequality to decreasing mobility.

Newer research updates notions of what drives U.S. mobility

In the years since our 2018 report was published, large administrative datasets have enabled researchers to gain a more comprehensive picture of the relationship between inequality and intergenerational mobility in the United States. There is still much to be learned about the relationship between inequality and intergenerational mobility, but recent research has started to uncover some of the mechanisms through which inequality may decrease mobility.

In 2019, for instance, economist Randall Akee of University California, Los Angeles, and the U.S Census Bureau’s Maggie Jones and Sonya Porter employed a new research strategy to analyze the trend of increased income inequality and decreased mobility by examining differences between and within racial and ethnic groups. Using administrative tax data linked to Census Bureau data on race, the authors find significant income stratification by race and a generally fixed income distribution.

Specifically, in the period from 2000 to 2014, all the groups the co-authors examined experienced higher levels of intra-group inequality. White and Asian Americans experienced the highest levels of intra-group inequality and the lowest levels of intra-group mobility. The opposite was true for Black, American Indian, and Hispanic Americans, where there was low intra-group inequality and high intra-group mobility. Yet the co-authors find that the latter groups have the lowest levels of intergroup, or overall, mobility and the highest probability of downward mobility, relative to White and Asian Americans. This results in a calcified income structure in which Black, American Indian, and Hispanic individuals are persistently clustered at the lower end of the income distribution, and White and Asian Americans tend to be on the higher end.7

New research in psychology and sociology also is shedding light on the relationship between inequality and mobility in the United States. For instance, psychologist Alexander Browman of the College of Holy Cross and his colleagues find that the perception of inequality can itself harm mobility prospects because experiencing and witnessing economic inequalities can decrease the likelihood of young people taking actions linked to economic success.8 The authors note several studies demonstrating that when people see evidence that society is unequal, their belief in upward mobility declines. They also show that students, particularly low-income students, demonstrate increased persistence in academic settings when shown evidence that mobility is likely. Browman and his colleagues underscore that low-income students must believe that opportunities offered to them are valuable and worth pursuing in order to actually pursue them.

Similarly, in a recent major literature review on the Great Gatsby Curve, sociologist Thomas DiPrete of Columbia University concludes that the structural forces driving increased inequality are simultaneously lowering absolute mobility, with lower average rates of income growth in the bottom 90th percentile of the income distribution resulting in lower mobility rates.

Yet DiPrete finds that research regarding inequality’s impact on relative mobility is less clear due to a combination of factors, including weaker relative mobility trends and multiple countervailing forces, such as those described in Bloome’s research mentioned above. Nevertheless, it is clear that understanding the effect inequality has on mobility requires close attention to social and institutional structures, not just human capital development.9

How does economic inequality limit the development of human potential?

All individuals are born with a certain amount of human potential. Yet the degree to which it is realized is dependent upon family, community, institutional factors, and myriad other structural barriers. The ways in which these barriers intersect and compound ultimately impacts intergenerational mobility.

Traditional approaches to understanding intergenerational economic mobility focus on the ways in which inequalities in opportunity during an individual’s childhood shape that person’s economic outcomes. In our 2018 report, however, we put forth a more expansive notion of potential by sharing research from three key channels—health, parental investments of time and money, and education—which show that the development of human potential begins before birth and how the connection between economic inequality and mobility builds over the course of an individual’s lifetime. Newer research backs up this framework and highlights new factors, such as social capital.

What follows are the key takeaways from our previous report, as well as more recent findings, in what the research argues are the essential channels that affect the development of human potential and, in turn, impact upward mobility in the United States.

Health

In our previous report, we highlighted a growing body of research demonstrating the links between economic inequality and health inequities. Of particular importance is prenatal health. Similar to other aspects of health, the distribution of prenatal health varies considerably by income, and a wide array of studies reviewed in the previous report concluded that the in utero period critically impacts the economic outcomes of an individual’s life.

Newer research examines the role expanding health insurance coverage plays in improving health and economic outcomes. Health insurance coverage improves both the quality of care that people receive and their health outcomes, so expanding health insurance coverage can contribute to economic mobility by improving health outcomes for mothers and children. The implementation of the Affordable Care Act in 2014 has helped reduce uninsured rates, particularly among people of color and other marginalized groups. Yet racial disparities in uninsurance persist.

In 2021, the uninsured rate for White people was 7 percent, compared to 19 percent and 11 percent for Hispanic and Black people, respectively, whereas in 2010, the uninsured rate among White people was 13 percent, compared to 33 percent and 20 percent for Hispanic and Black people, respectively.10 And that progress has continued. According to a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services report, the national uninsured rate was at an all-time low of 7.7 percent in early 2023.11

Access to appropriate care is critical, especially during and after pregnancy. Yet stark disparities in maternal and infant outcomes continue to persist in the United States, despite notable increases in insurance coverage and medical advancements. Indeed, according to a 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation report, in comparison to White women, Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders have higher shares of not only preterm and low birthweight births but also births in which they receive delayed or no prenatal care at all.12

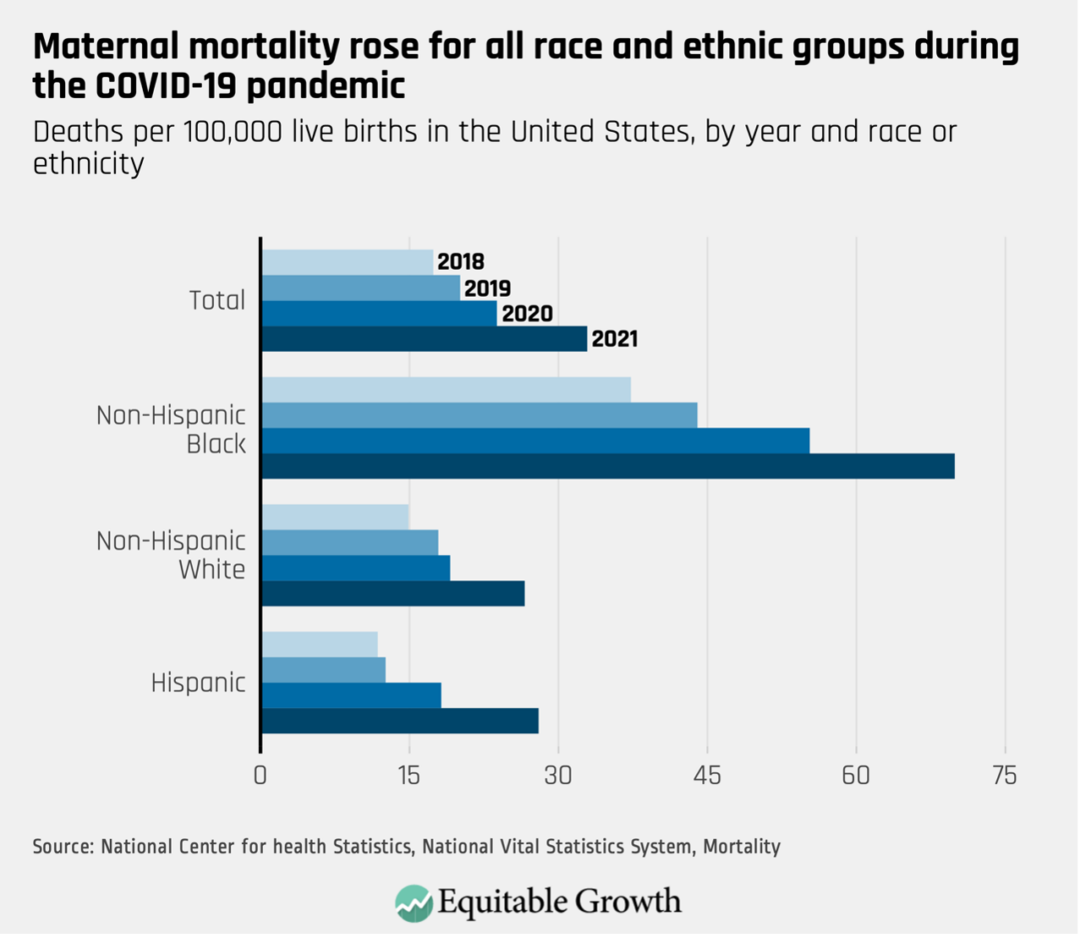

This is all the more troubling when considering that maternal mortality—the death of a woman while pregnant or 42 days after childbirth not due to accidental or incidental reasons—is increasing in the United States across age and racial groups. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

This increase in maternal mortality is due in part to the COVID-19 pandemic but also is influenced by other factors, including women getting pregnant at older ages and the rise of chronic health conditions.13 As Figure 1 shows, Black women are at a much greater risk of maternal mortality, and while there are multiple reasons why, including the ones just listed, a major factor unique to Black women is what medical professionals refer to as “allostatic load,” or the physiological effects of chronic stress, such as that caused by systemic racism and poverty, which, over time, makes one age more quickly.14

Relatedly, there is growing appreciation among researchers that mental health, in addition to physical health, is a threat to children’s mobility prospects. A 2019 Brookings Institution report pulled together decades of research to make the case that maternal depression has important consequences for economic mobility. Maternal depression is about twice as common in families with incomes below the federal poverty line, compared to those with incomes that are twice the federal poverty line or greater. Research also shows that the children of depressed mothers exhibit slower cognitive development, which, in turn, damages their economic mobility prospects.15

As there is a well-established link between parental health, child well-being, and life outcomes, reducing health inequities—including but going beyond expanding health insurance coverage—is critical for improved economic mobility.

Parental investments of money and time

Money is one way that parents support their children that we detailed in our previous report. A 2014 study by Georgetown University’s Bradley, for example, finds that income volatility experienced in childhood affects both their educational attainment and household income as adults.16 And research continues to underscore the compounding impact on children who grow up in low-income households.

In 2021, Kerris Cooper and Kitty Stewart of the London School of Economics conducted a literature review of 54 peer-reviewed studies to understand the evidence proving the causal relationship between household financial resources and children’s health, cognitive, and socio-behavioral outcomes.17 They find that “children from low-income households do worse in life in part because of low-income,” and that most of the evidence in the studies they review confirms that children’s cognitive and schooling outcomes in particular are hurt as a result of having little income. Cooper and Stewart also find that income levels in the period before birth is especially important for a child’s health outcomes.

In addition to income, wealth levels also have been found to impact human capital development. Parents’ savings and wealth affect the ways in which they can invest in their children’s potential, particularly in terms of educational opportunity. In the United States, purchasing a home in a high-performing school district is one of the most common ways that parents invest in their children’s potential.18 Parental wealth similarly plays an important role in their children’s enrollment in and completion of postsecondary education. Studies find that young adults in the top income quartile receive nearly three times as much financial support for postsecondary education from their parents as those in the bottom half of the income distribution.19

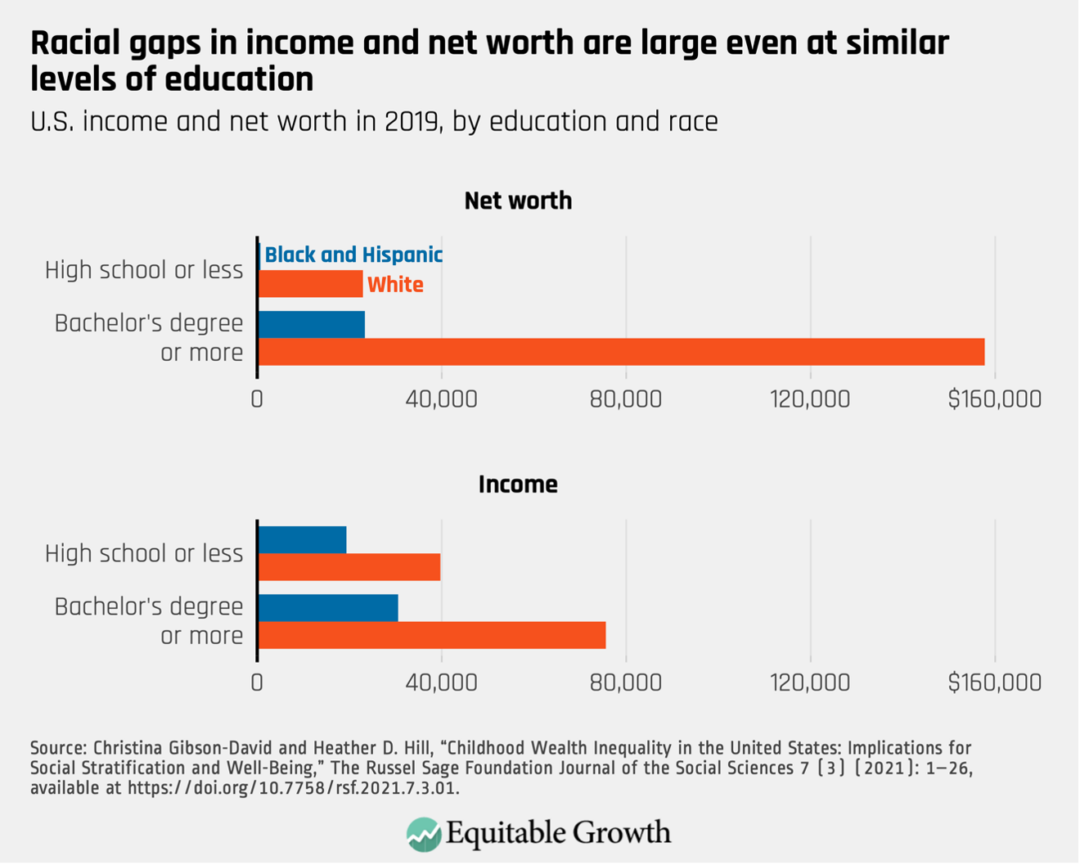

Recent research backs up the importance of wealth—and the vast racial disparities that persist in the United States. In their 2021 study, public policy professors Christina Gibson-Davis at Duke University and Heather D. Hill at the University of Washington analyze data from the Federal Reserve Board’s 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances and find that the top 10 percent of wealthiest households with children account for more than 80 percent of all wealth among all households with children. Compared to households with White children, which have median wealth levels of close to $64,000, the authors find that households with Black children have a median wealth of $808 (or 1 cent for every dollar in households with White children), and that households with Hispanic children have a median wealth of $3,175 (or 5 cents for every dollar in households with White children).20

Gibson-Davis and Hill’s analysis also finds that stark racial wealth differences across households with children persist after adjusting for parent education levels. Black and Hispanic households where a parent has a bachelor’s degree hold only $400 in additional wealth, on average, compared to White households where parents have a high school diploma or less. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Wealth, rather than income, has far more of an impact on academic and behavioral development of children from early childhood through adolescence, with very significant differences between low-wealth and high-wealth households.21 After controlling for income differences and other family characteristics, studies find that children raised in low-wealth households score lower on reading and math assessments and experience more behavioral problems and psychological stress than children raised in wealthier households.

Another way that parents support their children is time. In our previous report, we summarized how parents’ socioeconomic status dictates how much and what kind of time they spend with their children. Mothers with a college education tend to spend more time with their children, aiding their cognitive development, when compared to mothers with lower levels of educational attainment.22 Unpredictable work schedules, night-shift work, and lower education levels are some of the major reasons why low-income parents are unable to invest time in their children in the same ways that high-income families do.

Yet new research suggests that time-investment gaps between low-income and high-income parents have narrowed over the past several decades. In their 2023 literature review, public policy professor Ariel Kalil of the University of Chicago and her colleagues highlight that between 1988 and 2012, book ownership and library visits among low-income parents and children increased, and parental engagement differences between high-income and low-income parents fell from 8 hours per week to 3 hours per week by the late 2010s.23

Utilizing data from the National Household Education Survey, Kalil and her colleagues find that between 1979 and 2019, high-income parents attended school events at twice the rate of low-income parents. Yet they also find this gap narrows significantly by 2019 due to high-income parents attending fewer events while low-income parents attended these events at consistent rates to previous years. Low-income parents’ attendance at parent-teacher association meetings also increased over this time, which helped close the time gap between them and high-income parents.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence of teleworking and work-from-home arrangements rose dramatically. According to a Pew Research Center poll from March 2023, more than a third of workers in the United States who are able to telework are now doing so full time.24 As the early days of the pandemic illustrated, there are stark differences in who is afforded the safety and privilege to work from home, and these inequalities continue to grow. A recent study by Harvard Business Review showed that remote work arrangements are far more likely for higher-income positions than low-income ones, with more than 30 percent of jobs with salaries around $200,000 offering some level of remote work.25

More research is needed to determine whether the growing rise in work-from-home arrangements for high-income individuals will make the class gap in parental time—and subsequently child outcomes—worse.

Education

In our previous report, we highlighted the nuanced ways educational inequities have played a role in shaping intergenerational mobility. In fact, inequities at each level of education have their own attendant roles in an individual’s life cycle. Research demonstrates, for example, that substantial inequities exist in U.S. families’ abilities to invest in high-quality early child care—a critical time in a child’s early cognitive development—with higher-income families able to afford higher quality care centers.26 Studies also find that high-quality universal pre-Kindergarten for children ages 3 and 4 enhances human capital outcomes for all children, especially children from low-income families.27

Between Kindergarten and 12th grade, academic achievement gaps by income persist, and at least part of this gap is driven by the differential growth in cognitive skills for advantaged children, compared to disadvantaged children.28 And once in college, high-income students tend to be more prepared and, due to factors such as legacy admissions and athletic recruitment, are also admitted to elite schools at far higher rates than lower income students.29

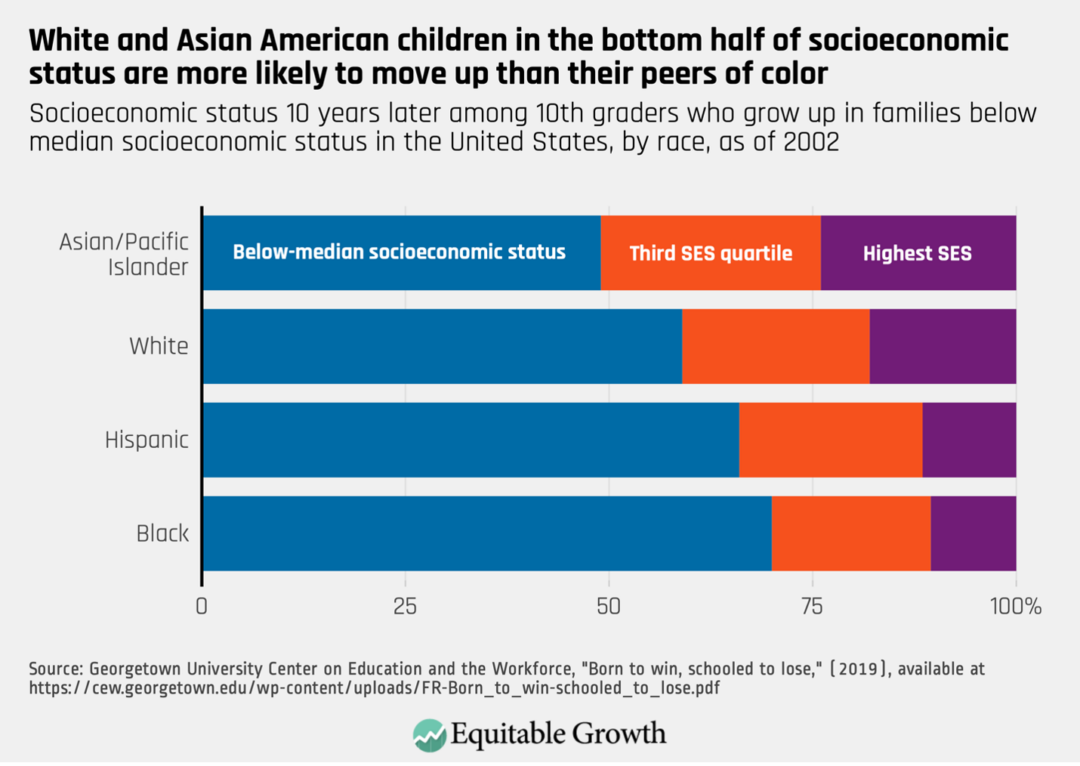

Recent research confirms the relationship between income and educational achievement, and thus upward mobility. In 2019, the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce published a comprehensive report, in which it demonstrates the falsity of the commonly held belief that education is a great equalizer and the key pathway to achieving the American Dream.30

The researchers find that if high-achieving Kindergarteners were from poor families, they were less likely to fully actualize their potential as they got older, due to the absence of protections that parents of higher socioeconomic status can offer to their children. Conversely, the researchers find, Kindergarteners who are struggling academically but are from higher socioeconomic backgrounds will often still receive support, complete college, and secure a well-paying job as a young adult.

As the authors write, this “gap doesn’t exist because affluent children are smarter than poor children—it’s because income and social status provide access to environments that allow children to develop to their full potential, all but ensuring their success.”31 Indeed, they continue, “the highest-SES (socioeconomic status) students with bottom-half math scores are more likely to complete a college degree than the lowest-SES students with top-half math scores.” The impact of families’ low socioeconomic statuses follows their children into young adulthood and varies significantly by race, with Hispanic and Black children from low socioeconomic status backgrounds struggling the most. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

What happens between childhood and adulthood to cement this reduced mobility? In 2023, Harvard’s Chetty and his colleagues look at college admission data and post-college outcomes, and find that graduates from Ivy-plus schools (those in the Ivy League, plus Stanford University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Duke University, and the University of Chicago) disproportionately hold the highest-income jobs in the United States.32 Controlling for SAT and ACT scores, they find that these schools admit students from high-income families at more than double the rate they admit students from low- or middle-income families. Another study by Chetty and his co-authors in 2020, which looks at the 1980 to 1982 Harvard cohorts, finds that more than 70 percent of students enrolled came from household incomes of $111,000 or higher, whereas only 3 percent were from families with household incomes below $25,000.33

Nonacademic criteria, such as legacy status, extracurricular activities, and athletic recruitment, play a big role in these higher admission rates for better-off students, even though they are not associated with post-college outcomes. Chetty and his colleagues find in their 2020 study that students with legacy status are no more likely to get admitted to other Ivy-plus schools than their peers who do not have legacy status, which means that their increased likelihood of getting accepted to the school they ultimately attend is due to parent association, not stronger credentials.

Ivy-plus schools also tend to rank students from high-income families higher on extracurricular activities than they do low- or middle-income students. Given that students from higher income backgrounds are likely to go to private high schools or have greater means to participate in extracurricular activities, these findings demonstrate how lack of access to resources and attention in childhood—coupled with income discrimination during the college admission process—hinder intergenerational mobility. Chetty and his colleagues conclude that “income-neutral allocations of students to colleges (conditional on test scores) would itself reduce the intergenerational persistence of income by 15 percent.”34

Social capital

A new area of focus in mobility research in the realm of developing human potential is the role of social connections. Sociologists have long pointed to social capital as an important determinant of mobility, of which social connections are one part. Chetty and others from Harvard’s Opportunity Insights analyzed 21 billion friendships on Facebook to determine the level of cross-class friending across the United States. Unsurprisingly, they find that friend groups are often segregated by income. They also find that in areas of the country where low-income individuals have more high-income friends, mobility is higher, leading them to conclude that having high-income friends appears to help low-income individuals develop the social capital that helps them escape poverty.35

In fact, the researchers report that the level of cross-class friendship in a community is a more powerful predictor of mobility than any other community feature studied. They then examine two determinants of cross-class connectedness: exposure to people of other classes and “friending bias,” which measures the extent to which high- or low-income individuals have a preference for friends within their own class. These two factors are about equally important in determining the level of cross-class friendship in the United States overall, but their relative importance varies considerably across the country. For instance, In New York county, which encompasses Manhattan, they find high levels of exposure to people of different classes, but also high levels of friending bias, resulting in only middling levels of connectedness overall.36

How does economic inequality limit the deployment of human potential?

An inclusive economy is only possible if individuals can develop their potential and contribute their talents. Unfortunately, too many barriers stand in the way of many individuals in the United States maximizing their full potential.

Below, we look at two key roadblocks to opportunity that were discussed in our 2018 report: structural changes to the U.S. labor market and persistent racial, ethnic, and sexual discrimination. We then turn to newer areas of research into barriers to mobility in the United States: reproductive rights and the labor market and Unemployment Insurance discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Changes to the U.S. labor market

Our previous report specifically looked at two new developments in the U.S. labor market, fissuring and job ladders, both of which have significantly contributed to lower mobility. Fissuring, or the outsourcing of various functions, such as a firm outsourcing janitorial functions to a contractor, complicates employer-employee relationships by making them far less straightforward than they had been previously.

Moreover, broken job ladders contribute to the ineffective development of human potential—which, as we described above, is critical for an inclusive economy. When taken together, our previous report concluded that these phenomena have contributed to reducing mobility by eroding benefits and making it harder for workers to progress to better jobs.

In recent years, more economists have begun to recognize the role that monopsony—broadly described as firms’ power to set wages—plays for numerous economic outcomes, including wage suppression and markdowns, or the gap between the value workers generate for the firm and their actual wages.37 Two recent studies illuminate the ways in which increased monopsony power might be linked to depressed economic mobility.

In a 2022 Equitable Growth working paper, economists Gregor Schubert of the University of California, Los Angeles, Anna Stansbury of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Bledi Taska of Lightcast find that increasing employer concentration—a measure of monopsony power—can lead to a 2 percent to 7 percent decrease in wages for approximately 10 percent of the U.S workforce.38 And a 2020 Equitable Growth working paper by economists Anna Sokolova and Todd Sorensen at the University of Nevada, Reno performs a meta-analysis examining all available research at the time, finding that, depending on the method of study used, U.S. employers have the power to mark down wages between 7 percent and 58 percent.39

Taken together, this new research on monopsony suggests labor market structures related to employer power and wage-setting may provide further areas of inquiry for mobility research. This is especially true as it relates to how earnings may be suppressed for certain workers over the course of a lifetime, compared to previous generations.

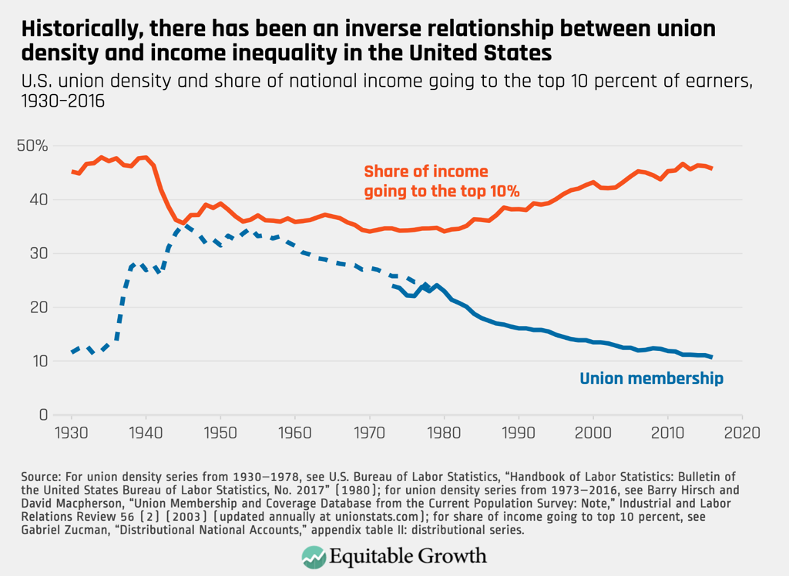

A significant reason monopsony and its consequences are possible today is that U.S. workers’ bargaining power is at historic lows. Since the 1980s, union density began to precipitously decline and has yet to recover. As power shifted away from workers and toward firms that were able to concentrate their power to set—and suppress—wages, inequality and mobility trends worsened.

Research shows, for example, that when U.S. union density was at its highest, from 1940 to 1970, organized labor represented a greater share of workers of color and workers with lower levels of education—who have historically been clustered in low-wage jobs—raising their wages and narrowing the gap between incomes at the top and the bottom of the income ladder.40 But as union membership rates subsequently declined and the composition of unions changed, the equalizing effect of organized labor became less powerful. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

This trend of lower unionization rates across the U.S. labor force had deleterious effects on racial and gender inequality. One study finds that the decline in union membership explains 13 percent to 30 percent of the Black-White weekly wage gap among women.41

Yet there are signs of a resurgence in labor organizing. In 2023, for instance, there were more than 400 strikes—the most of any year since 2000, according to data collected by the Labor Action Tracker, a collaboration between Cornell University’s Industrial and Labor Relations School and the University of Illinois’ Labor and Employment Relations School.42 Work stoppages in 2023 involved more than 450,000 workers, the second-most stoppages since 1986, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.43

These labor gains have nevertheless been met with predictable pushback, including a multipronged lawsuit filed by large corporations, such as Amazon.com Inc., SpaceX, and Trader Joes. These firms argue that the National Labor Relations Board—the federal agency that protects the rights of private-sector workers to join unions—is unconstitutional.44

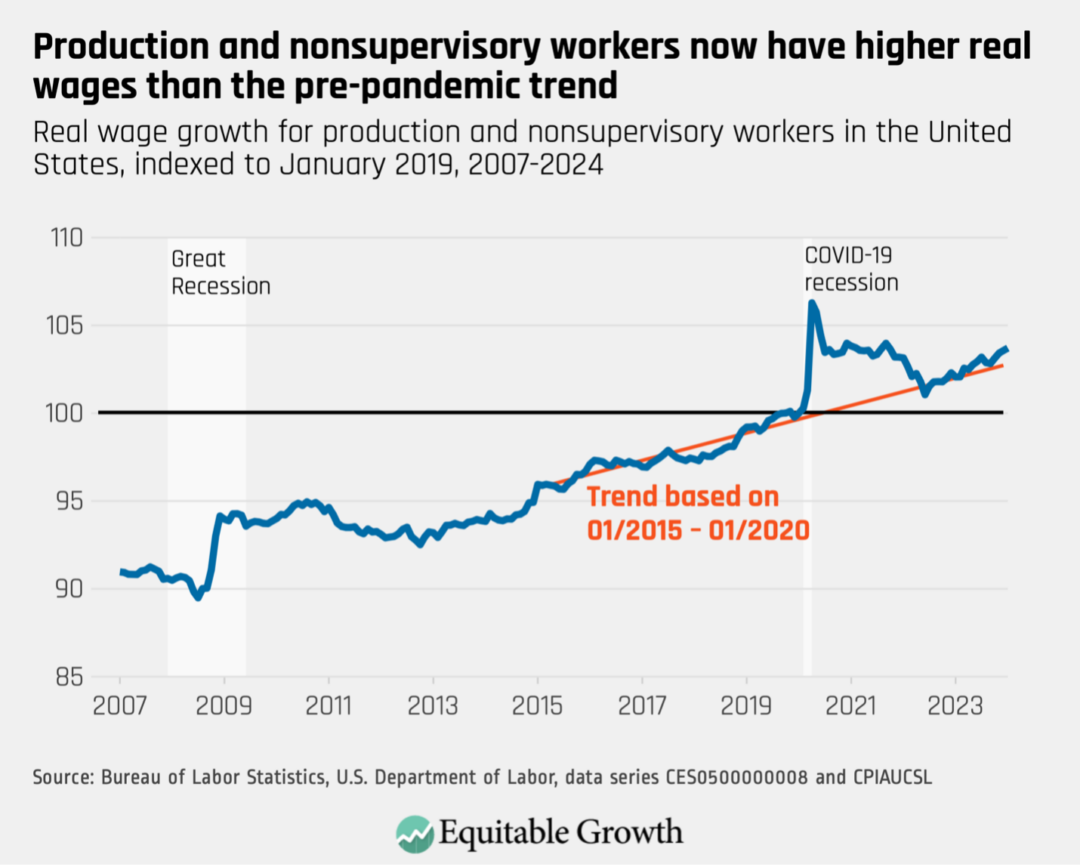

Other recent labor market developments include positive wage trends in the post-pandemic economy. In their 2023 study, economists Arindrajit Dube of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, David Autor of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Annie McGrew of UMass Amherst find that labor market tightness during the recovery from the COVID-19 recession led to wage compression, with workers at the bottom and in the middle of the U.S. income distribution having the highest wage growth in 2023.45 Dube and his co-authors find that wages grew for workers in the middle quintile by nearly 4 percent over the course of 2023 (adjusted for inflation), whereas in 2019, the median inflation-adjusted wage grew by just 1 percent over the prior year.46

Indeed, the wages of production and nonsupervisory workers—a category that includes most low- and middle-income workers and represents about 80 percent of the workforce—have kept up with, and even exceeded, pre-pandemic trends. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

Persistent gender, racial, and ethnic discrimination

Our previous report detailed how race and gender are intertwined with economic status in ways that hinder the full deployment of human potential in the United States. Women’s labor force participation and earnings have increased over the decades, which means women today are making more than their mothers. Yet compared to their male peers, women are still underpaid. At the time of our previous report in 2018, the gender pay gap stood at about 80.5 percent, which cost the average female worker more than $400,000 in lifetime earnings, relative to a similarly situated male worker.

Recent research shows that women continue to face discrimination in the labor market, despite increases in educational attainment. According to a 2023 Pew Research Center report, the gender pay gap in the United States has minimally closed over the past two decades. In 2002, women earned 80 cents for every dollar earned by men. By 2022, this had increased by only two cents, to 82 cents for every dollar earned by men. Despite women completing college at a higher rate than men, gender disparities in wages persist and are comparable between men and women who have a college degree and men and women who don’t.47

It is also significant that women ages 25 to 34 may begin their careers with earnings parity, but studies show the gap in earnings widens as they get older, with their pay dropping most sharply between ages of 35 and 44.48 This is the age bracket at which most women (66 percent) have at least one child at home. In addition to pay inequity, women continue to face sexual discrimination and occupational segregation.49

Our previous report also highlighted how racial and ethnic discrimination also impacts the earnings and career trajectories of both men and women workers of color. Researchers have demonstrated how this discrimination begins with the job application process, such as when resumes with “White sounding” names are selected by employers for a call-back much more than resumes with “Black-sounding” names.50

Researchers continue to document systemic discrimination against workers of color, with especially negative consequences for women of color. In her research on discrimination, City University of New York economist Michelle Holder notes that Black women face a reinforcing confluence of a gender wage gap and a racial wage gap—or what she terms a “double gap”—that results in $50 billion of involuntarily forfeited wages annually.51

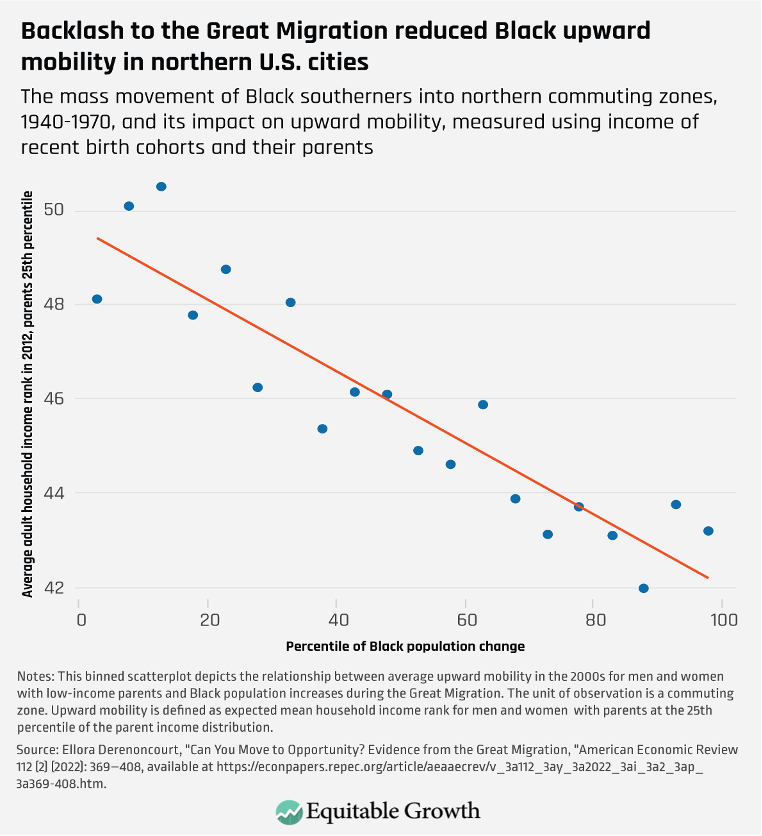

A 2022 working paper for the Equitable Growth Working Paper series by economist Ellora Derenoncourt of Princeton University explores the persistence of systemic discrimination against Black Americans. She first constructed a novel database to analyze the impact of Black Americans’ Great Migration out of the South in the early to mid-20th century on the future generations of these migrants. She then finds that the gains accrued by the first generation of Black Americans during the Great Migration dissipated with future generations. By the third generation, she finds that Black Americans whose grandparents migrated from the South to the North in the early 20th century have the same or worse economic outcomes as Black Americans whose grandparents did not move away from the South.

Derenoncourt explains that this erosion is due, at least in part, to the backlash in Northern cities to the Great Migration, where segregation was entrenched through White flight to the suburbs and public investments were siphoned from social infrastructure to policing. According to Derenoncourt, without this backlash, the Black-White mobility gap would be 27 percent smaller.52 (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

In 2018, Harvard University’s Opportunity Insights researchers analyzed longitudinal data for the U.S. population from 1989 to 2015 to better understand intergenerational inequalities and find that they vary significantly across racial groups.53 Asian Americans experience higher rates of upward income mobility than all other racial groups and, when their parents are born in the United States, Asian American children experience intergenerational mobility at similar levels as White Americans. Hispanic Americans, although trailing behind Asian and White Americans, have slightly lower levels of income intergenerational mobility than White Americans, while Black Americans and American Indians have the lowest rates of upward mobility and are the most likely to experience downward mobility.

The researchers also find that virtually everywhere in the country, Black boys have lower rates of upward mobility than White boys. Even if they grow up in the same neighborhood and have comparable family income, Black boys fare worse than White boys when they get older. Yet the important takeaway is that these disparities are largely due to environmental factors, which can be changed—and if changed, have the potential to improve future outcomes. According to the authors, “Black men who move to better areas—such as those with low poverty rates, low racial bias, and higher father presence—earlier in their childhood have higher incomes and lower rates of incarceration as adults.”54

Reproductive rights and the labor market

Since the publication of our 2018 report, new political economic circumstances regarding severe restrictions to reproductive care and bodily autonomy require new assessments of the state of economic mobility. The reason: In June 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court, in its ruling on Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, voted to overturn decades of precedent regarding an individual’s constitutional right to abortion and allow individual states to enact their own laws either protecting or restricting—and in some cases, banning—access to abortion.

Since the Dobbs ruling, some states have been swift in implementing bans on abortion such that half of all U.S. women now live in a state with limited or zero access to abortion.55 Prior to Dobbs, almost 4 in 10 abortions (38 percent) were among Black women, one-third (33 percent) were among White women, and 1 in 5 abortions (21 percent) were among Hispanic women. Additionally, the majority of women who attempt to access abortion live below the poverty line.56 As such, this decision has very strong racial, gender, and economic implications for pregnant people accessing abortion and future generations of children.

An immense body of research links reproductive rights with better economic outcomes for women. Research suggests that accessing abortion increases women’s participation in the workforce57 and their likelihood of obtaining a managerial position.58 Eliminating women’s access to abortion services also has been shown to reduce women’s years of education by more than 9 percent and decrease lifetime earnings by 3 percent.59 American University of Beirut economist Ali Abboud finds that for young women, especially young Black women, access to abortion before the age of 21—which is the opportune time to develop human capital—increases their wages significantly.60

The Turnaway Study, a longitudinal study that examines the effects of unwanted pregnancy on women’s lives, finds that women who seek an abortion but are not able to obtain one face a higher likelihood of experiencing poverty 4 years later.61 Another study finds that 6 months after being denied an abortion, women were three times more likely to be unemployed.62 University of Michigan economist Sarah Miller and her colleagues linked credit data to the Turnaway Study and find that women who were denied an abortion due to gestational limits experienced great financial stress the year in which they gave birth, and in many cases for years afterwards.63 Unpaid debts doubling in size and credit rankings decreasing were two of the main consequences for these women.

Most of these impacts have been well-known in the academic literature for some time, but they underscore the threat that the Dobbs decision could pose to economic mobility. These negative outcomes will directly decrease mobility for women over their lifetimes. But they also will have a significant impact on the next generation, as roughly half of women who get abortions have below-poverty-level income, which will pose barriers to mobility for their children.

Unemployment Insurance discrimination during the pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic and recession revealed and exacerbated deep fragilities built into the U.S. economy, especially regarding gender and racial inequities. One stark example is access to Unemployment Insurance. Unemployment Insurance allows low- and middle-income households to smooth their consumption in times of economic stress. In addition to supporting these workers directly, Georgetown University economist Bradley Hardy finds that parents’ income volatility has a negative impact on education attainment for their children.64

While most eligible workers do not receive the UI benefits they are entitled to, due in part to not knowing about their eligibility and bureaucratic barriers, there are significant inequities when comparing workers who do receive benefits and those who do not. For instance, economists Eliza Forsythe and Hesong Yang of University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign find that disparities in receiving UI benefits by gender and race persisted despite expansions to UI benefits through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act in 2020. As a percentage of eligible recipients, they find women were less likely to receive UI benefits than men by as much as 8 percentage points. Black UI-eligible workers, meanwhile, were less likely to receive benefits than White UI-eligible workers, also by as much as 8 percentage points.65

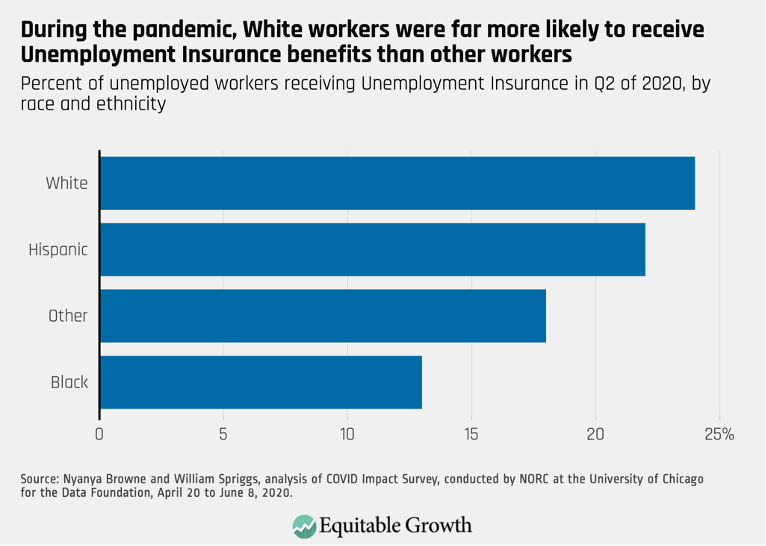

Other recent research during the COVID-19 recession confirmed the persistence of racial disparities in receiving UI benefits. In an analysis of survey data between April 2020 and June 2020, economists Nyanya Browne and (the late) William Spriggs of Howard University find that Black workers were approximately half as likely to receive UI benefits as White workers, with 13 percent of Black workers receiving such benefits, compared to 24 percent of White workers.66 (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7

To be sure, disparities in UI recipiency are longstanding, and these discrepancies prior to the most recent recession are well-documented. For instance, in an analysis of data from 1986 through 2015, economists Elira Kuka of George Washington University and Bryan Stuart of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia find that Black workers were 24 percent less likely than White workers to receive UI benefits.67

In addition to racial inequities in UI recipiency, there are also gaps in the amount of UI benefits received. Economists Daphné Skandalis of the University of Copenhagen, Ioana Marinescu of University of Pennsylvania, and Maxim N. Massenkoff of the Naval Postgraduate School find in their analysis that the replacement rate—or the unemployment benefits received relative to prior earnings—was 18.3 percent lower for Black claimants than White claimants. When examining the factors contributing to this gap, they find that after adjusting for work history—which can impact prior earnings that need replacement and the likelihood of losing one’s job—the replacement rate for Black claimants was 8.4 percent lower than White claimants, due entirely to differences in state rules concerning Unemployment Insurance.

The co-authors also find that the share of Black UI claimants is negatively correlated with the amount of UI benefits. Their analysis finds that the weekly UI benefit amount decreased by $9 for every 10 percentage point increase in the share of Black UI claimants.68

Conclusion

The 2018 Equitable Growth mobility report provided key insights into many potential mechanisms driving mobility in the United States. In doing so, the report offered a framework for organizing the immense field of economic mobility research.

This report updates and refines that framework by including new research developments—such as studies analyzing wages lost to monopsony power or the relevance of social capital—and new political economic circumstances, including the COVID-19 recession and the dismantling of reproductive rights post-Dobbs. These updates attempt to provide a nuanced and comprehensive picture of the state of U.S. economic mobility, as well as provide entry points for policy interventions and further research.

Though questions remain, it is clear that the reality of intergenerational mobility in the United States is markedly different from the bootstrapping story often told—a story that has unhelpfully informed dominant policy approaches for the past few decades. As the copious research attests, honing in on the individual level misses the many other pathways and structures that affect economic mobility. Though the sheer number of factors influencing mobility can seem daunting, they are also opportunities for policymakers to intervene and improve the livelihoods of all Americans today and well into the future.

About the Authors

Hiba Haroon

Hiba Haroon is the founder of un(jaan), where she works in personal and group settings to heal minds, bodies, and spirits from the effects of colonialism and white supremacy. Previously Hiba was a senior associate at the Annie E. Casey Foundation, where she led the foundation’s Southern Partnership to Reduce Debt and Family Stability and Assets work. She has worked in the nonprofit sector for over a decade to address racial economic inequalities. Haroon completed her undergraduate studies in international studies and philosophy at the University of St. Thomas, Houston and her graduate studies in cultural foundations of education at Syracuse University.

Shaun Harrison

Prior to joining Equitable Growth, Shaun Harrison was a research assistant at the Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race at Columbia University. He holds a B.A. in sociology from The George Washington University, and an M.A. in American studies from Columbia University.

Special thanks to Equitable Growth special assistant Catherine Wu, who assisted in the final production and formatting of the report.

End Notes

1. Randall Akee, Maggie Jones, and Sonya Porter, “Race Matters: Income Shares, Income Inequality, and Income Mobility for All U.S. Races,” Demography 56 (3) (2019): 999–1021.

2. Elisabeth Jacobs and Liz Hipple, “Are today’s inequalities limiting tomorrow’s opportunities?” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2018).

3. Jacobs and Hipple, “Are today’s inequalities limiting tomorrow’s opportunities?”

4. Miles Corak, “Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility,” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 27 (3) (2013): 79–102.

5. Raj Chetty and others, “Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective.” Working Paper 24441 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018).

6. Deirdre Bloome, “Income Inequality and Intergenerational Income Mobility in the United States,” Social Forces 93 (3) (2015): 1047–1080.

7. Randall Akee, Maggie Jones, and Sonya Porter, “Race Matters: Income Shares, Income Inequality, and Income Mobility for All U.S. Races,” Demography 56 (3) (2019): 999–1021.

8. Alexander S. Browman and others, “How economic inequality shapes mobility expectations and behaviour in disadvantaged youth” Nature Human Behaviour 3 (2019): 214–220.

9. Thomas A. DiPrete, “The Impact of Inequality on Intergenerational Mobility,” Annual Review of Sociology 46 (2020): 379–398.

10. Nambi Ndugga and Samantha Artiga, “Disparities in Health and Health Care: 5 Key Questions and Answers” (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2023).

11. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “New HHS Report Shows National Uninsured Rate Reached All-Time Low in 2023 After Record-Breaking ACA Enrollment Period,” Press release, August 3, 2023.

12. Ndugga and Artiga, “Disparities in Health and Health Care: 5 Key Questions and Answers.”

13. Donna L. Hoyert, “Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2021” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023; Kathy Katella, “Maternal Mortality Is on the Rise: 8 Things To Know” (Yale Medicine, 2023).

14. Katella, “Maternal Mortality Is on the Rise: 8 Things To Know.”

15. Richard V. Reeves and Eleanor Krause, “The Effects of Maternal Depression on Early Childhood Development and Implications for Economic Mobility” (Washington: Brookings Institution, 2019).

16. Bradley L. Hardy, “Childhood Income Volatility and Adult Outcomes,” Demography 51 (5) (2014): 1641–1665.

17. Kerris Cooper and Kitty Stewart, “Does Household Income Affect Children’s Outcomes? A Systematic Review of the Evidence,” Child Indicators Research 14 (2021) 981–1005.

18. Fabian T. Pfeffer and Martin Hällsten, “Mobility Regimes and Parental Wealth: The United States, Germany, and Sweden in Comparison.” Working Paper 500 (German Institute for Economic Research, 2012).

19. Robert F. Schoeni and Karen E. Ross, “Material Assistance from Families during the Transition to Adulthood.” In Richard A. Settersten Jr., Frank F. Furstenberg, and Ruben G. Rumbaut, ed., On the Frontier of Adulthood: Theory, Research, and Public Policy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005).

20. Christina Gibson-Davis and Heather D. Hill, “Childhood Wealth Inequality in the United States: Implications for Social Stratification and Well-Being,” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 7 (3) (2021): 1–26.

21. Portia Miller and others, “Wealth and Child Development: Differences in Associations by Family Income and Developmental Stage,” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 7 (3) (2021): 154–174.

22. Jonathan Guryan, Erik Hurst, and Melissa Kearney, “Parental Education and Parental Time with Children,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 22 (3) (2008): 23–46.

23. Ariel Kalil, Samantha Steimle, and Rebecca M. Ryan, “Trends in Parents’ Time Investment at Children’s Schools During a Period of Economic Change,” AERA Open 9 (2023).

24. Kim Parker, “About a third of U.S. workers who can work from home now do so all the time” (Washington: Pew Research Center, 2023).

25. Peter John Lambert and others, “Research: The Growing Inequality of Who Gets to Work from Home” (Harvard Business Review, 2023).

26. Deborah A. Phillips and others, “Child Care for Children in Poverty: Opportunity or Inequity?,” Child Development 65 (2) (1994): 472–492.

27. Elizabeth Cascio, “Does Universal Preschool Hit the Target? Program Access and Preschool Impacts.” Working Paper 23215 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2017).

28. Sean F. Reardon, “The Widening Academic Achievement Gap Between the Rich and the Poor: New Evidence and Possible Explanations.” In Greg J. Duncan and Richard J. Murnane, ed., Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances (New York: Russell Sage Foundation Press, 2011).

29. Richard Reeves, Dream Hoarders: How the American Upper Middle Class Is Leaving Everyone Else in the Dust, Why That Is a Problem, and What to Do about It (Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 2017).

30. Anthony P. Carnevale and others, “Born to Win, Schooled to Lose: Why Equally Talented Students Don’t Get Equal Chances to Be All They Can Be” (Washington: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, 2019).

31. Ibid.

32. Raj Chetty, David J. Deming, and John Friedman, “Diversifying Society’s Leaders? The Determinants and Causal Effects of Admission to Highly Selective Private Colleges.” Working Paper 31492 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023).

33. Raj Chetty and others, “Income Segregation and Intergenerational Mobility Across Colleges in the United States,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135 (3) (2020): 1567–1633.

34. Ibid.

35. Raj Chetty and others, “Social capital I: measurement and associations with economic mobility,” Nature 608 (2022): 108–121.

36. Raj Chetty and others, “Social capital II: determinants of economic connectedness,” Nature 608 (2022): 122–134.

37. Carmen Sanchez Cumming, “A primer on monopsony power: Its causes, consequences, and implications for U.S. workers and economic growth” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2022).

38. Gregor Schubert, Anna Stansbury, and Bledi Taska, “Employer Concentration and Outside Options” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2021).

39. Anna Sokolova and Todd Sorensen, “Monopsony in Labor Markets: A Meta-Analysis” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020).

40. Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming, “Factsheet: U.S. occupational segregation by race, ethnicity, and gender” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020).

41. Jake Rosenfeld and Meredith Kleykamp, “Organized Labor and Racial Wage Inequality in the United States,” American Journal of Sociology 117 (5) (2012): 1460–1502.

42. “Labor Action Tracker,” available at https://striketracker.ilr.cornell.edu/.

43. Drew Desilver, “2023 saw some of the biggest, hardest-fought labor disputes in recent decades” (Washington: Pew Research Center, 2024).

44. Robert Iafolla, “Amazon Joins SpaceX, Trader Joe’s in Challenging Labor Board (1)” (Bloomberg Law, 2024).

45. David Autor, Arindrajit Dube, and Annie McGrew, “The Unexpected Compression: Competition at Work in the Low Wage Labor Market.” Working Paper 31010 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023).

46. “State of Working America Data Library,“ available at https://www.epi.org/data/#citations.

47. Rakesh Kochhar, “The Enduring Grip of the Gender Pay Gap” (Pew Research Center, 2023).

48. Ibid.

49. Carly McCann, Donald Tomaskovic-Devey, and M. V. Lee Badgett, “Employer’s Responses to Sexual Harassment” (Center for Employment Equity, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2018); David A. Cotter, Joan M. Hermsen, and Reeve Vanneman, “The Effects of Occupational Gender Segregation across Race,” The Sociological Quarterly 44 (1) (2008): 17–36.

50. Marianne Bertrand and Sendhil Mullainathan, “Are Emily and Greg More Employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination,” American Economic Review 94 (4) (2004): 991–1013.

51. Michelle Holder, “The ‘Double Gap’ and the Bottom Line: African American Women’s Wage Gap and Corporate Profits” (Roosevelt Institute, 2020).

52. Ellora Derenoncourt, ”Is moving to a new place key to upward mobility for U.S. workers and their families?” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2022).

53. Raj Chetty and others, “Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 135 (2) (2020): 711–783.

54. Ibid.

55. Weiyi Cai and others, “Half of U.S. Women Risk Losing Abortion Access Without Roe” The New York Times, May 7, 2022.

56. Samantha Artiga and others, “What are the Implications of the Overturning of Roe v. Wade for Racial Disparities?” (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2022).

57. Martha J. Bailey, “More Power to the Pill: The Impact of Contraceptive Freedom on Women’s Life Cycle Labor Supply,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 121 (1) (2006): 289–320.

58. Kelly Jones, “At a Crossroads: The impact of abortion access on future economic outcomes.” Working Paper (American University, Department of Economics, 2021).

59. Diego Amador, “The Consequences of Abortion and Contraception Policies on Young Women’s Reproductive Choices, Schooling and Labor Supply,” Documento CEDE 43 (2017).

60. Ali Abboud, “The Impact of Early Fertility Shocks on Women’s Fertility and Labor Market Outcomes.” Scholarly Paper (Social Science Research Network, 2019).

61. Sarah Miller, Laura R. Wherry, and Diana Greene Foster, “What Happens after an Abortion Denial? A Review of Results from the Turnaway Study” AEA Papers and Proceedings 110 (2020): 226–230.

62. Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health, “Socioeconomic outcomes of women who receive and women who are denied wanted abortions” (2018).

63. Sarah Miller, Laura R. Wherry, and Diana Greene Foster, “The Economic Consequences of Being Denied an Abortion.” Working Paper 26662 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020).

64. Bradley L. Hardy, “Childhood Income Volatility and Adult Outcomes,” Demography 51 (5) (2014): 1641–1665.

65. Eliza Forsythe and Hesong Yang, “Understanding Disparities in Unemployment Insurance Recipiency” (2021).

66. Ava Kofman and Hannah Fresques, “Black Workers Are More Likely to Be Unemployed but Less Likely to Get Unemployment Benefits” (New York: ProPublica, 2020).

67. Elira Kuka and Bryan A. Stuart, “Racial Inequality in Unemployment Insurance Receipt and Take-Up.” Working Paper 29595 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021).

68. Daphné Skandalis, Ioana Marinescu, and Maxim N. Massenkoff, “Racial Inequality in the U.S. Unemployment Insurance System.” Working Paper 30252 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2022).

Related

In conversation with Sasha Killewald

In Conversation with Jonathan Fisher

Explore the Equitable Growth network of experts around the country and get answers to today's most pressing questions!