Overview

President Joe Biden, in November 2021, signed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act into law, providing $1.2 trillion in new government investments to create millions of jobs, increase U.S. economic competitiveness abroad, and help address the climate crisis. The multiple provisions of the law are now or will soon:

- Create hundreds of thousands of jobs within the transportation sector, with investments in passenger and freight rail, bridges, roads, airports, ports, and public transit

- Guarantee safe drinking water by eliminating the nation’s lead-tainted service lines, especially in disadvantaged communities that need refurbishing the most

- Reduce supply chain bottlenecks to help ease inflation and lower the cost of goods and services

- Build a national network for electric vehicle charging stations

- Manufacture solar panels, wind farms, batteries, and electric vehicles to help address climate change

- Make high-speed internet affordable and accessible

These much-needed investments are not only delivering significant macroeconomic benefits now, and will continue to do so well into the future, but also potentially addressing longstanding economic inequalities. Indeed, the new infrastructure investments and the jobs created by these investments can reduce these inequalities, increase unionization, and address climate change because they rest on sound economic principles.

In this issue brief, we demonstrate why the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 and its focus on equitable growth is good economics. First, we outline the ways in which the law helps to address urgent needs currently facing the United States. Next, we discuss how the law’s focus on equity, unionization, and climate are crucial for a healthy economy with strong, stable, and broadly shared growth. We conclude by discussing the impact the law can have on addressing inequalities in our economy and share recommendations for a path forward.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act addresses urgent needs

The passage of this law in November 2021 signaled a commitment by the federal government to reinvigorate physical infrastructure in the United States. The bulk of the investments are going toward roads and bridges, power systems, railways, broadband, water systems, and public transit. The deterioration of the nation’s physical infrastructure is well-documented. Following World War II, the United States made public investments to build an interstate highway system, airports, a network of waterworks, and expanded port facilities and other infrastructure that significantly boosted the country’s economic output. Much of this infrastructure is now in critical need of repair.

Take roads, for example. According to the latest research from the American Society of Civil Engineers, almost half of U.S. roads are in poor or mediocre condition due to wear and tear. Research indicates this deterioration costs motorists nearly $130 billion each year in extra vehicle repairs and operating costs.

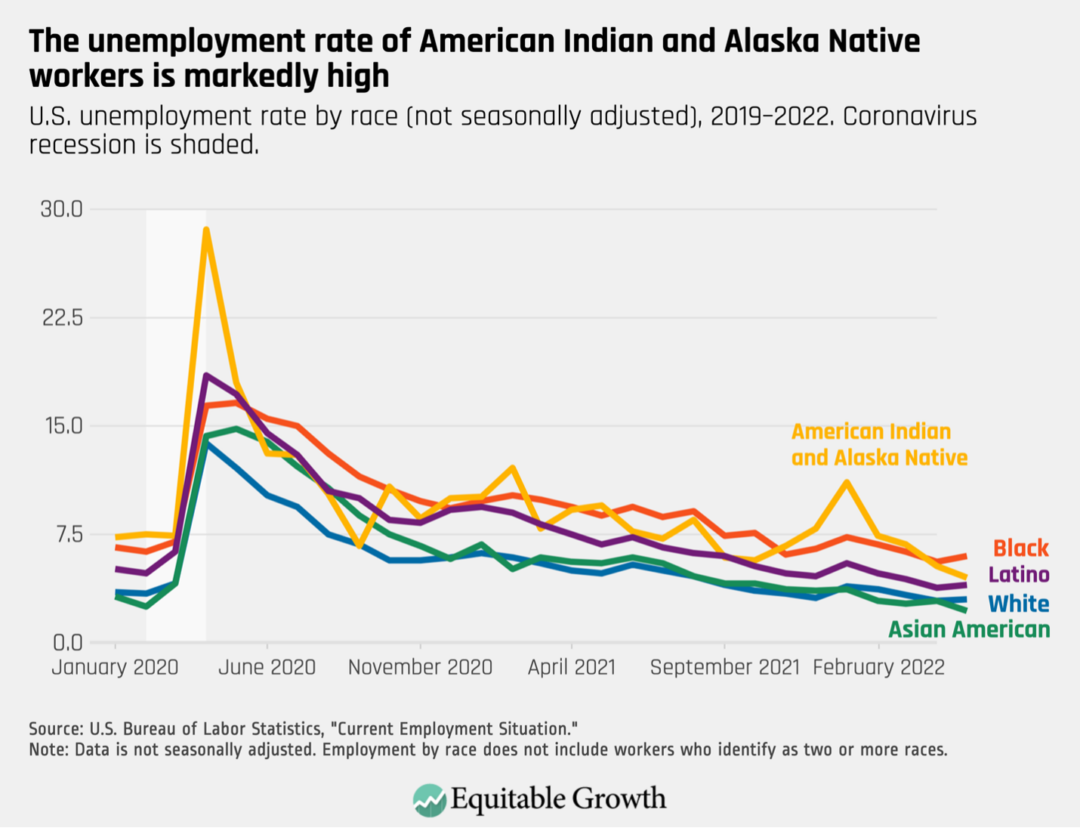

Water infrastructure is another example of an area badly needing investment. Neglected and old water infrastructure poses a serious public health risk, with some estimates showing that up to 10 million U.S. households and 400,000 schools and child care centers lack safe drinking water. This lack of clean drinking water disproportionately affects Black, Latino, and Indigenous individuals.

In addition to improving older infrastructure, expanding infrastructure such as broadband is imperative. Some estimates indicate that 30 million people in the United States live in areas where broadband infrastructure is inadequate. According to the latest data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the United States has the second-highest broadband costs among the 35 developed OECD countries studied.

Disparities in access to quality broadband infrastructure are pronounced. Research by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development finds a strong association between household income and in-home connectivity—a pattern that persists across both rural and urban communities. The study finds that, overall, two-thirds of U.S. adults ages 18 and older had access to broadband internet in their homes, but just 41 percent of adults with household incomes of less than $20,000 had access, while 90 percent of adults with household incomes higher than $100,000 had access.

Moreover, a report by Dominique Harrison of the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies finds that in rural counties in the Southern region of the country with populations that are at least 35 percent Black, 38 percent of Black residents in these areas lack home internet access. This is nearly double the rate of White residents in the same counties. The consequences of not having internet access are severe. Students need broadband to access the internet to do homework and apply to colleges. Working families need it to apply for jobs and to more easily access various government services, and seniors are increasingly reliant on broadband accessibility to connect to the growing world of telehealth.

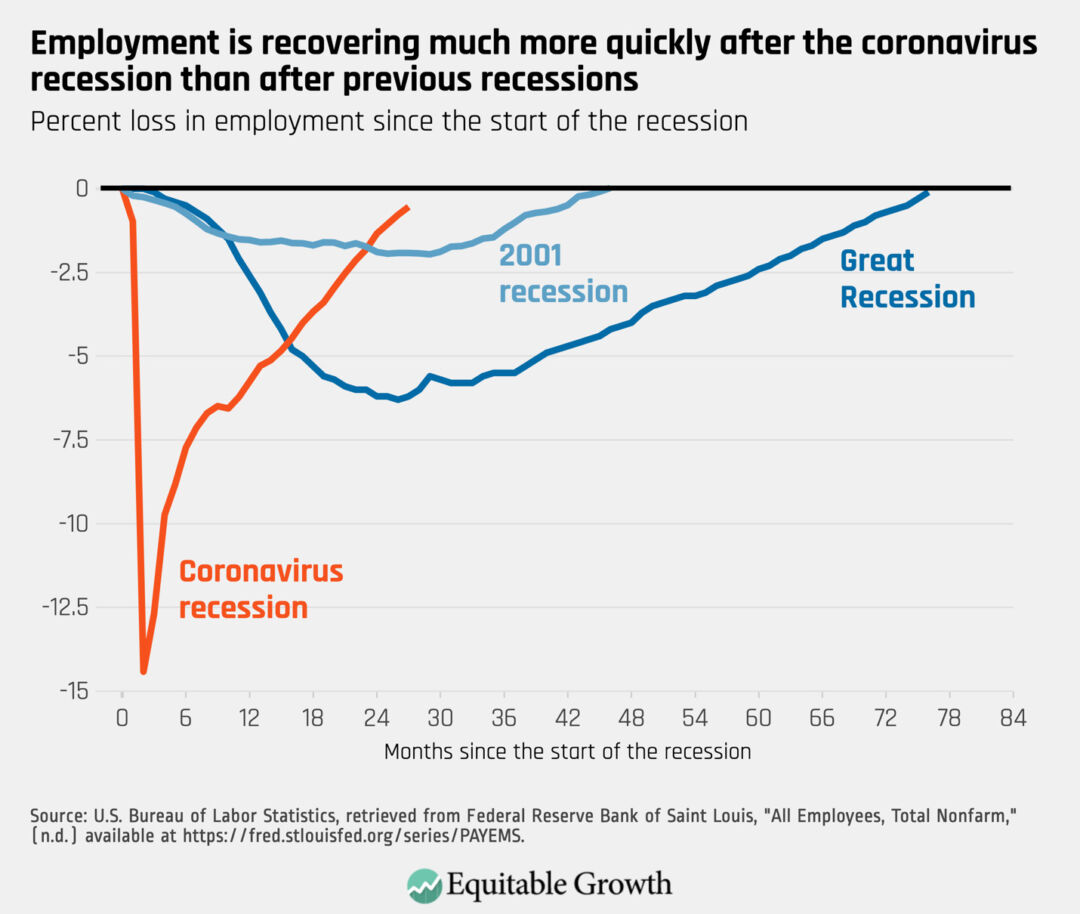

There are macroeconomic benefits to the new investments happening or starting to happen because of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act as well. Investments in infrastructure generally tend to yield a high rate of return, meaning increases in public investments in infrastructure significantly result in increased output and productivity. It is well-documented that infrastructure investments have large multipliers—that is, a proportionally higher increase in Gross Domestic Product for every dollar increase in investment—with infrastructure spending having substantially higher multipliers than other fiscal interventions, such as tax cuts.

In particular, Mark Zandi and Bernard Yaros of Moody’s Analytics write that at the apex of economic growth generated by the new infrastructure investments in 2023, real GDP is forecast to increase 2.9 percent, compared to 2.3 percent if only the American Rescue Plan (which was passed in March 2021) had been passed into law. Zandi and Yaros also project that in the long term, the U.S. economy receives a bump in productivity growth due to the increase in the stock of public infrastructure. Recent projections made by the Congressional Budget Office, which take the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act into account, suggest productivity will increase 1.5 percent on average over the next decade.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act also encompasses the important need to address economic inequity, unionization, and climate in any large job-creation efforts in the United States. Each of these issues cannot be easily separated from one another. In fact, these components frequently intersect, forming a matrix that provides a more comprehensive picture of economic growth and well-being. We next examine why these components matter and how they contribute to building an economy with broadly shared growth.

Economic equity, unionization, and climate

The investments that the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act makes to reduce economic inequalities, increase unionization, and address climate change rest on sound economic principles. We outline some of the ways the law addresses these three pillars and examine how these pillars are important for promoting strong, broadly shared economic growth.

One of the ways the law helps to ameliorate inequalities in the U.S. labor market is by mandating that the “overwhelming majority” of the funds will be subject to Davis-Bacon requirements. These requirements ensure that contractors pay workers on construction projects—in which the new funding makes major investments—a prevailing wage, so that local wages, labor markets, and workers won’t be undercut. While there are limitations to this approach, as we discuss below, it is nevertheless one tool to raise the wage floor and, similar to minimum wage increases, can address gender and racial inequalities and wage divides.

These public investments also focus on tackling climate change, such as $7.5 billion in investments to build out a national network of electric vehicle chargers in the United States. These kinds of investments will result in the creation of green manufacturing jobs. As one of the co-authors of this issue brief testified before the Joint Economic Committee, economic research demonstrates the importance of investments in green energy.

For instance, Columbia University economist Joseph Stiglitz, alongside other colleagues, argues that renewable energy and energy efficiency investments typically have high multipliers, delivering even greater returns over time. They also tend to create more jobs, compared to fossil fuel investments, including ones that can’t be taken offshore, such as those in home energy retrofitting. Further, recent research from Ioana Marinescu of University of Pennsylvania and E. Mark Curtis of Wake Forest University suggests there is a pay premium for green jobs, especially for green jobs with a low educational requirement.

Moreover, according to recent research from Heidi Garrett-Peltier, an economist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, for every $1 million invested in renewable energy or energy efficiency, almost three times as many jobs are created than if the same money were invested in fossil fuels. Investing more money in the fossil fuel industry will not address high and growing unemployment rates. Indeed, the Federal Reserve is not even requiring companies to keep workers as a condition for getting loans in the fossil fuel industry.

Leah Stokes and Matto Mildenberger, both assistant professors of political science at the University of California, Santa Barbara, highlight that many U.S. unions maintain strong ties to carbon-intensive industries, such as auto manufacturing or heavy industry. By contrast, many jobs in the clean energy sector—from clean energy deployment to electric vehicle manufacturing—remain nonunionized.

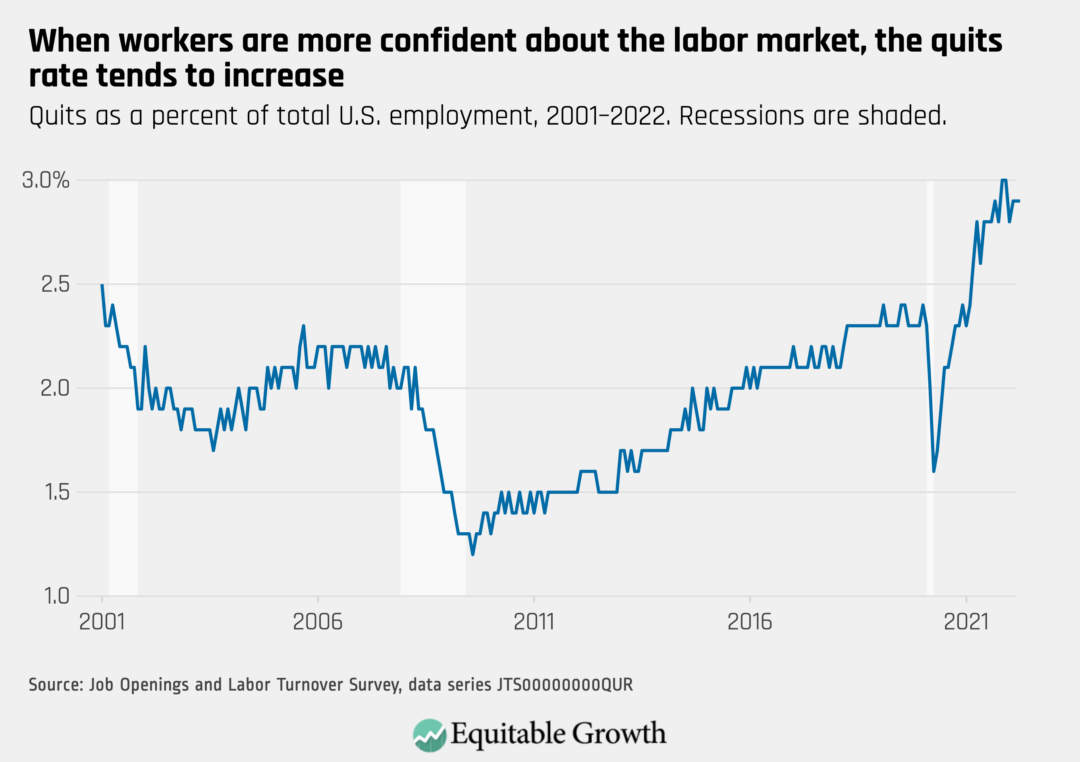

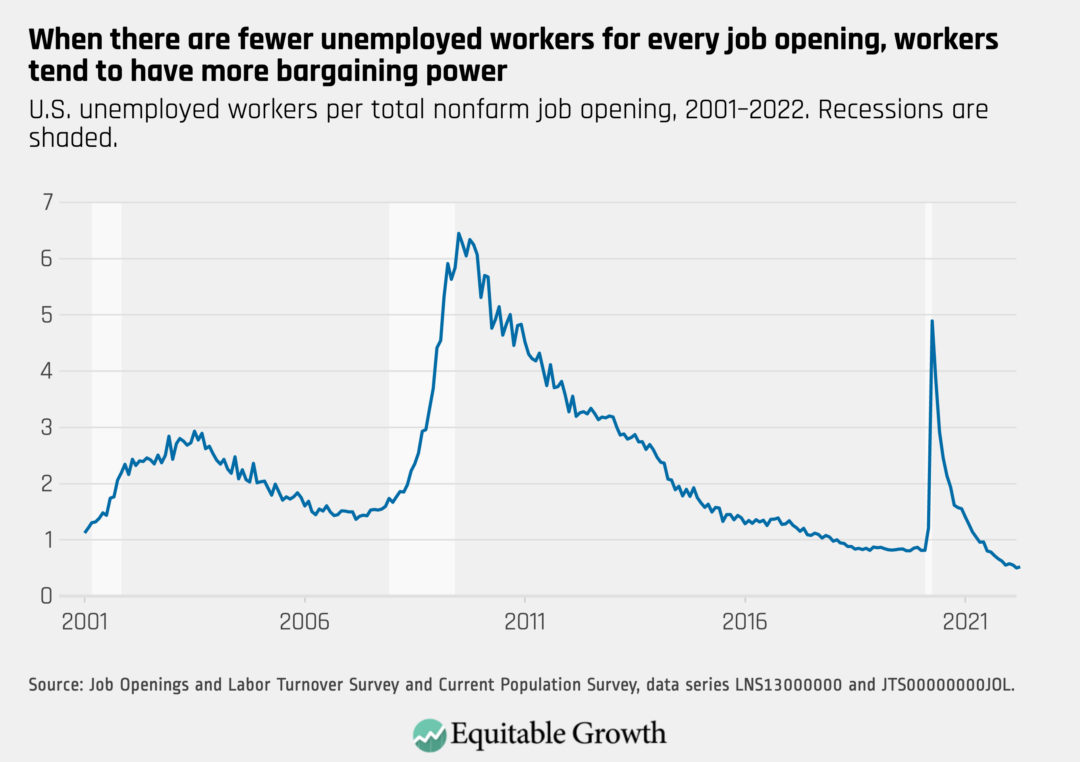

In part, this pattern reflects the decline in union participation across new U.S. industrial sectors. In order to address labor market disparities—such as gender and racial wage divides—government funding for clean energy projects should prioritize unionized jobs. Indeed, with funds dedicated to infrastructure projects that can help create unionized jobs, the 2021 infrastructure investment law takes a step in the right direction to increasing worker bargaining power.

The benefits of prioritizing unionized jobs for creating broadly shared growth cannot be understated. Unions are shown to have an inverse relationship with income inequality. Moreover, while union members have higher wages than their nonunionized peers—what researchers call the union wage premium—organized labor may create conditions that make all workers better-off. Strong unions are able to set job-quality standards that nonunion businesses have to meet in order to compete for workers, which is known as the spillover effect.

Unions play an important role in addressing racial inequality. Even though the majority of union members were White and male during the height of the U.S. labor movement in the mid-20th century, organized labor strongly supported redistributive public policies that contributed to narrowing racial and gender pay gaps. Research shows, for example, not only that there is a larger union wage premium for Black workers, but also that unions reduce racial animosity among workers.

There are other ways these new investments address racial equity. In addition to investments in both water and broadband infrastructures discussed above, there are investments to clean up Superfund sites, which are contaminated sites caused by hazardous waste being dumped, left out in the open, or otherwise improperly managed. These sites include manufacturing facilities, processing plants, landfills, and mining sites. Investments in cleanup efforts will benefit Black and Hispanic communities, which, compared to predominantly White communities, are located disproportionately within 3 miles of a Superfund site.

Or consider the hundreds of thousands of new jobs that will be created over the course of a decade, alongside the quality—not just the quantity—of those jobs. Research by Kate Bahn of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth and Mark Stelzner of Connecticut College shows that characteristics specific to race and gender, such as the lower levels of wealth in Black and Latino households and increased household responsibilities for women, make workers of color and women more susceptible to exploitation by employers, with Black women and Latina workers facing both race and gender penalties and thus being exploited even further.

These hurdles reduce worker power by restricting workers’ ability to seek other, better-paying, and more interesting jobs, which gives employers more power to reduce wages for these particular groups of workers. Research conducted by one of the co-authors of this issue brief demonstrates that Black women experience a “double gap,” which is the reinforcing confluence of the gender wage gap and the racial wage gap. The double gap helps to explain why Black women workers earn the least in wages, on average, compared to their working counterparts among White men, White women, and Black men. The double gap costs Black women workers approximately $50 billion in involuntarily forfeited earnings—a large and recurring annual loss to the Black community.

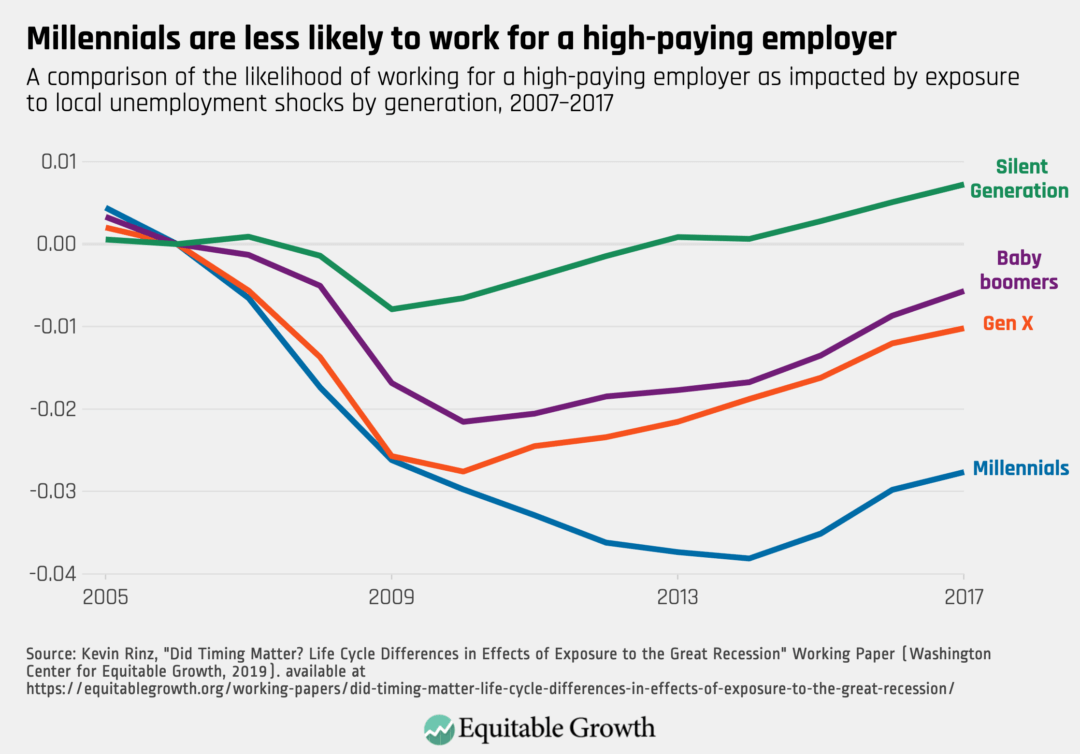

For decades, the prevailing wisdom in policymaking circles was that there is a trade-off between equity and economic growth. This conventional belief argues that reducing economic inequality would require such heavy-handed interference in markets that growth would be stifled. Yet there is mounting evidence that suggests otherwise. For the past near-half century, economic inequality has risen in income and wealth, yet the U.S. economy has not experienced stronger or more sustained economic growth. Advancing economic policies that seek to redress these structural inequalities will benefit all U.S. workers and their families and help promote an economy with strong, stable, and broadly shared growth. Failing to address these inequalities leaves our whole economy vulnerable.

Robert Lynch of Washington College finds that closing racial and gender disparities would have resulted in an increase in U.S. GDP of $7.2 trillion in 2019. According to Lynch, GDP could have totaled $28.6 trillion instead of $21.4 trillion that year. Lynch also finds that federal, state, and local tax revenues would have been $1.82 trillion higher in 2019, while the overall U.S. poverty rate would have dropped from 10.5 percent to 6.6 percent, lifting 12.2 million people out of poverty. What’s more, there would have been a $429 billion improvement in the finances of the U.S. Social Security system in 2019.

Remaining questions and recommendations

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 is a historic piece of legislation that makes much-needed investments in traditional infrastructure, yet many of these investments in traditional infrastructure will create jobs in industries traditionally dominated by men. Questions remain about how to ensure the jobs created by this law are equitably distributed and do not leave women, including women of color, at the margins of the U.S. economy yet again.

Black women, for example, experience significant occupational segregation, with five occupations accounting for more than half of all the jobs in which Black women work. This is consistent with a large body of economic literature that shows women, including Black women, tend to be crowded primarily in low-wage occupations. These occupations, in fact, are often low wage precisely because of their association with Black women, especially compared to other occupations that may require similar levels of training or skills but are dominated by White male workers.

Indeed, there exists an overrepresentation of Black women in certain industries and occupations—often in care and service sectors— resulting from myriad factors, including the systemic devaluation of certain kinds of work, discrimination, and uneven occupational integration. In general, the overwhelming majority of domestic workers are women. More than half of domestic workers are Black, Latina, or Asian American and Pacific Islander women, with some studies finding that more than 90 percent of domestic workers are women of color.

Significant questions remain about how the jobs created by the Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act will be equitably distributed and targeted, given significant levels of occupational segregation within the U.S. economy. It will therefore be imperative to improve pathways for people underrepresented in infrastructure jobs to be able to obtain these jobs, such as creating pathways for women to have construction jobs. Another way forward is by making investments in social infrastructure, such as the care economy, which remains key to overcoming the endemic economic divides across race, gender, and income.

Questions also remain regarding how investments are incorporated into transportation infrastructure more equitably. It’s not clear, for example, how these new investments in transportation infrastructure will affect equitable access to transportation and how increases or decreases in transportation equity will affect growth, since the economic consequences of inequitable transportation options are often borne by low-income people, who are disproportionately people of color. To better understand this question, we need better measurement.

With the significant investments in transportation, it will be important to ensure that inequities in transportation are addressed. These inequities include “transportation insecurity,” a term coined by Alix Gould-Werth of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, Jamie Griffin of the University of Michigan, and Alexandra Murphy of the University of Michigan, which describes the condition of being unable to regularly move from place to place in a safe or timely manner because of a lack of resources necessary for transportation.

A diagnosis of problems surrounding transportation are only as good as the tools to measure it. In this vein, the U.S. Department of Transportation could adopt the Transportation Security Index, which was also created by the aforementioned scholars. The Transportation Security Index, which is modeled after the Food Security Index, is composed of items that ask respondents about symptoms of transportation insecurity, such as taking a long time to plan out everyday trips, feeling stuck at home, or worrying about burdening others with requests for assistance with transportation. As such, it is an important tool that can be used to determine whether people can get to where they need to go in a safe or timely manner and evaluate interventions that are designed to strengthen the U.S. economy by moving people from a state of transportation insecurity to one of security.

Moreover, while the prioritization of union jobs in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act is an important first step, there are still significant actions worth considering. Current challenges to unionization, such as rulings by the U.S. Supreme Court that have limited the ability of public-sector unions to collect dues, as well as made it more difficult for workers overall to band together and sue their employers for workplace misconduct, calls for new advocacy efforts for legislative remedies to enable more effective unionization.

One such example is the Clean Slate Agenda, which was developed by Sharon Block and Benjamin Sachs of Harvard Law School. They created a series of proposals for structural legal changes that would protect workers and give them the ability to countervail employers’ power. Their recommendations include:

- Sectoral collective bargaining that enables unions to negotiate with industries rather than individual firms, increasing organized labor’s power to lift wages, set industrywide standards, and reach agreements that benefit a greater number of workers

- Laws that expand and protect workers’ right to engage in collective action, including the creation of funds that allow workers to engage in strikes or walkouts without jeopardizing their financial security

- An inclusive labor law reform that places the need to address gender, racial, and ethnic inequalities at its center by extending protections to domestic, incarcerated, and undocumented workers, as well as expanding rights and protections for independent contractors

Other proposals include the creation of labor market institutions, such as wage boards, which set minimum pay standards by industry and occupation and lead to wage gains for those at the bottom and middle of the income distribution. Enacting the PRO Act, which would make it easier for workers to organize into unions, would also curtail employers’ ability to misclassify workers as independent contractors, who do not have the right to unionize under federal U.S. law.

These measures would expand workers’ rights and allow unions to balance power in the labor market, ensuring that the economic gains they create are broadly shared.

Conclusion

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 is a major piece of legislation that rests on sound economic principles to help the U.S. economy reach its full potential. By placing greater focus on equity, unionization, and climate, the law and its swath of new investments are a step in the right direction. Yet to achieve strong, stable, and broadly shared growth, further investments and policies, such as those outlined above, are needed.

—Michelle Holder is the president and CEO of the Washington center for Equitable Growth. Shaun Harrison is her research assistant.