How investments in early care and education can fuel U.S. economic growth immediately and over the long term

Fast facts

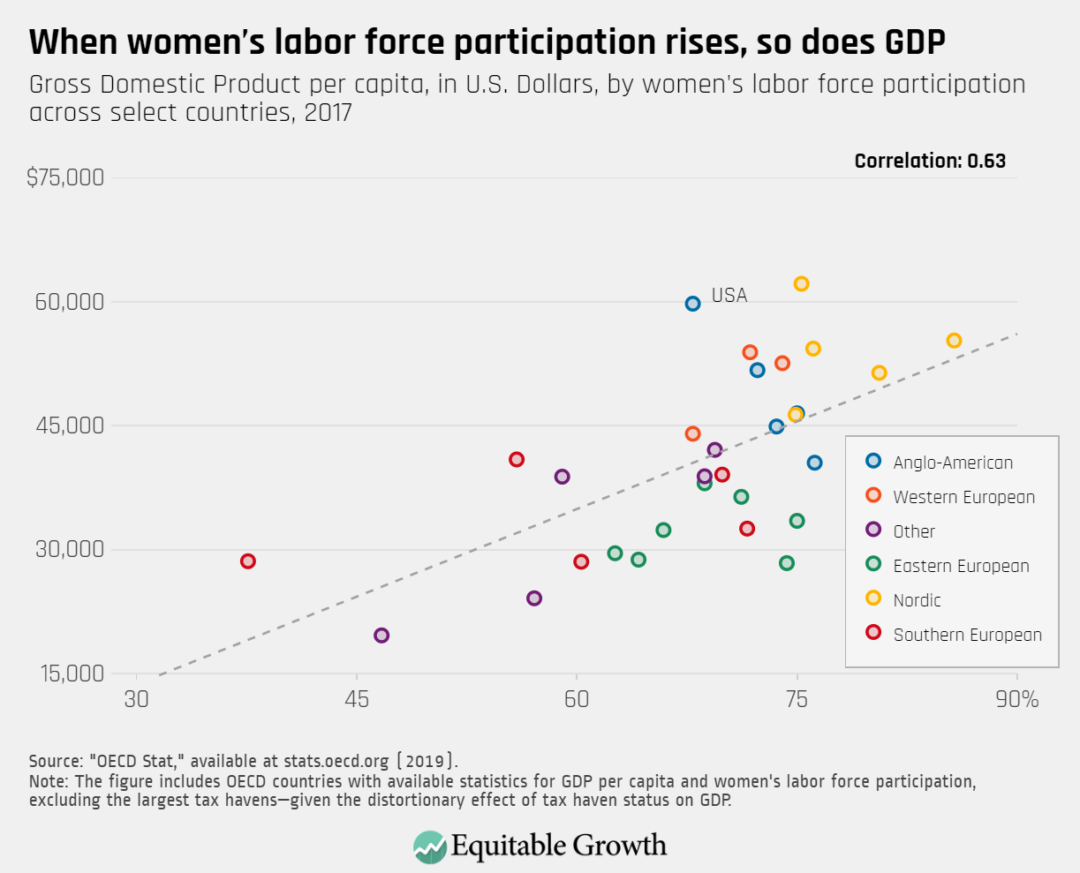

- Insufficient child care options can prevent parents who wish to work from doing so, with mothers often bearing the brunt of this challenge. Among parents who wish to work, child-rearing tends to interfere more with women’s labor supply and employment outcomes than with men’s. This leaves potential economic growth unrealized, as women’s labor force participation is significantly associated with Gross Domestic Product growth.

- High-quality early care and education provides critical socialization and learning opportunities when the brain is developing rapidly and is particularly responsive to the outside environment. Young children in pre-Kindergarten programs experience positive developmental outcomes and are better prepared for school, scoring higher than their peers on standardized measures of reading, spelling, math, and problem-solving skills.

- Adequate funding is necessary for human capital development. Fully funding the subsidy programs and devoting resources for state-level agencies to assist providers in qualifying for subsidies are two ways in which greater public investment could increase child care availability and quality.

- Supporting child care workers is crucial for promoting quality care and human capital development. Using public funds to support higher compensation would help stabilize the child care workforce, ensuring that these workers can afford to stay in their jobs.

- Investing in the nation’s children is one of the safest bets policymakers can make. Research on early care and education programs finds that $1 in spending generates $8.60 in economic activity.

Overview

U.S. workers and their families are largely on their own when it comes to child care, despite evidence that the provision of child care delivers immediate and long-term economic benefits. For working parents facing competing priorities and lacking many child care options, the current child care market in the United States gives them a lot to consider. Do I trust this child care provider with my child? How much will care cost? How close is this child care provider to my home or school? Are the hours compatible with my schedule? Is the environment safe, friendly, and stimulating for my child?

What parents probably aren’t considering is how their child care choices can reverberate throughout the U.S. economy. From a macroeconomic perspective, however, child care decisions writ large are hugely consequential, whether it’s how families purchase care and what type of care to how these decisions affect the family breadwinners’ employers and then, the broader economy.

Despite the important role child care plays in U.S. families’ lives and the economy, the private market remains largely insufficient in meeting their needs. With more parents in the workforce, fewer children are living with a full-time, stay-at-home caregiver than in prior decades.1 Yet rising demand for child care has not translated into a similar rise in the supply of affordable, high-quality care.2

Roughly half of children live in so-called child care deserts, where there are insufficient licensed child care slots available to care for the local children. Even when parents can find care, it is often too expensive, exceeding the cost of public college in many states.3 And despite these high prices, child care workers are some of the lowest paid in the U.S. economy, subsisting on poverty wages that threaten their own families’ economic security.

This child care crisis in the United States did not develop by chance. The crisis is the result of decades of policy decisions that deprioritized helping families for the sake of arbitrary budget constraints and fears over, in the words of President Richard Nixon, the supposed “family-weakening implications” of a child care system that facilitates maternal employment—devaluing the critical work of women, primarily women of color, in the process.4

Publicly funded Kindergarten through 12th grade education has been the national norm for decades, yet the same approach has not been applied to early care and education—a term that encompasses traditional child care, pre-Kindergarten, and targeted programs such as Head Start. Policymakers at the local, state, and federal level have instead allowed a child care system to develop in which accessing care is treated as a matter of personal responsibility rather than a public goal, despite growing evidence that investing in a high-quality child care system is sound economic policy for all.

Researchers and scholars are now confirming what many parents already knew: The current child care market does not meet the needs of working families.5 This is not simply an issue for families with young children—accessible, affordable, and high-quality care also has the potential to generate substantial economic activity and growth that benefits the entire U.S. economy.6 This occurs by:

- Freeing up parents’ time and ability to work in the short term

- Supporting positive human capital development among children in the long term

- Improving working conditions and pay for millions of low-income child care workers

Unfortunately, the current child care market leaves these potential benefits to the U.S. economy unrealized. Public investment in child care can help correct this failure, facilitating economic gains for families, businesses, and the economy as a whole.

This report will explore the economic potential of an accessible, affordable, and high-quality child care system in the United States. The report begins by reviewing the research on how early care and education can boost short-term growth by facilitating labor force participation among parents. The report then discusses the significant long-term economic growth potential of high-quality care as it pertains to childhood development, school readiness, and other socioeconomic outcomes. It then analyzes how the United States can unlock this growth potential through greater public investment.

The report closes with a discussion of the overarching benefits of policies that aim to address the child care crisis and set the U.S. economy on the path for sustainable, broad-based growth. The bottom line: Addressing the child care crisis can improve families’ immediate economic security and well-being while accelerating U.S. economic growth in the long term.

Early care and education supports immediate U.S. economic growth

The economic story of the 20th century United States may be the expansion of women entering the U.S. labor market. While many women, particularly women of color and all single mothers, were in the labor force for centuries already, changing social norms and economic necessities around the Second World War prompted more married women to pursue careers outside of the home.

The shifting demographics of the U.S. workforce helped heteronormative, two-parent families remain economically stable, with gains in women’s hours worked and hourly pay offsetting loses by male earners over the decades.7 Women’s greater U.S. labor market participation also has been an economic necessity for single parents, mostly mothers, with whom roughly one-quarter of children live.8

A modern economy benefits when more people engage in the workforce or receive education or training to obtain a better job. At the same time, the private early care and education market has failed to address the greatest challenge facing many families: how to care for children when parents go to work or school. This apparent deficiency in the private market is likely hampering economic growth.

Indeed, following the explosive expansion of women in the workforce in the middle of the 20th century, labor force participation rates have stagnated in recent years. Economists and policymakers now suggest that insufficient child care and caregiving policies are preventing the United States from reaching its full economic potential.9

Insufficient child care options can prevent parents who wish to engage in the workforce from doing so, regardless of gender, but it is women who often bear the brunt of this challenge. Research using time-diary data—where participants record the number of minutes they spend each day on different activities—consistently finds that women still have the primary responsibility for child-rearing in most families. This is true regardless of family structure.

In one study, single, cohabiting, and married women spent up to twice as much time—4.8 hours, 5.8 hours, and 6 hours per day, respectively—on child care as comparable single, cohabiting, and married men, who spent 3.2 hours, 3.4 hours, and 3.1 hours per day, respectively, on child care.10 It is therefore unsurprising that among parents that wish to work, child-rearing tends to interfere with women’s work in the economy and their employment outcomes more than it does for men.11 As a result, policies that alleviate child care concerns would be expected to primarily improve maternal employment, though all parents would benefit.

Such improvements could lead to meaningful changes in the U.S. labor force. Growth in women’s labor force participation has slowed since the 1990s, and as of 2019, there remains a significant gender gap between the participation rate for men (69.2 percent) and women (57.4 percent).12 As documented elsewhere, the caregiving implications of closed schools and child care centers, along with other social distancing measures during the coronavirus pandemic, has only served to widen this disparity. The divide is largest for Hispanic workers, with an 18.5 percentage point difference in labor force participation between Hispanic woman and Hispanic men.

The United States once enjoyed a more sizable advantage, compared to its economic competitors, but U.S. labor force participation among prime working-age women now falls below the average of large, economically comparable nations. Gains in women’s labor force participation in a country is associated with higher Gross Domestic Product.13 U.S. GDP ranks high, compared to other nations, yet the nation’s insufficient care infrastructure may be leaving economic potential unrealized. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Put simply, when child care allows parents to work and the number of workers in the labor force increases, the economy grows. In this manner, the immediate consequences of providing child care are readily evident.

Accessible and affordable care helps ensure that parents who wish to work can do so

A new parent or new parents in the United States often encounter a pressing paradox after the birth of their children. With new children come new costs—approximately $12,980 annually per child for middle-income families.14 These costs could induce parents to return to the workforce after childbirth or even enter it for the first time. Doing so, of course, requires finding appropriate care for their new child or children, which can be costly and complicated. If a parent is not confident that their child or children are in a safe and nurturing environment through the day—because they cannot find or afford high-quality care—then the parent or parents may need to forgo work to focus on caregiving, which solves child care concerns but not their economic situations.

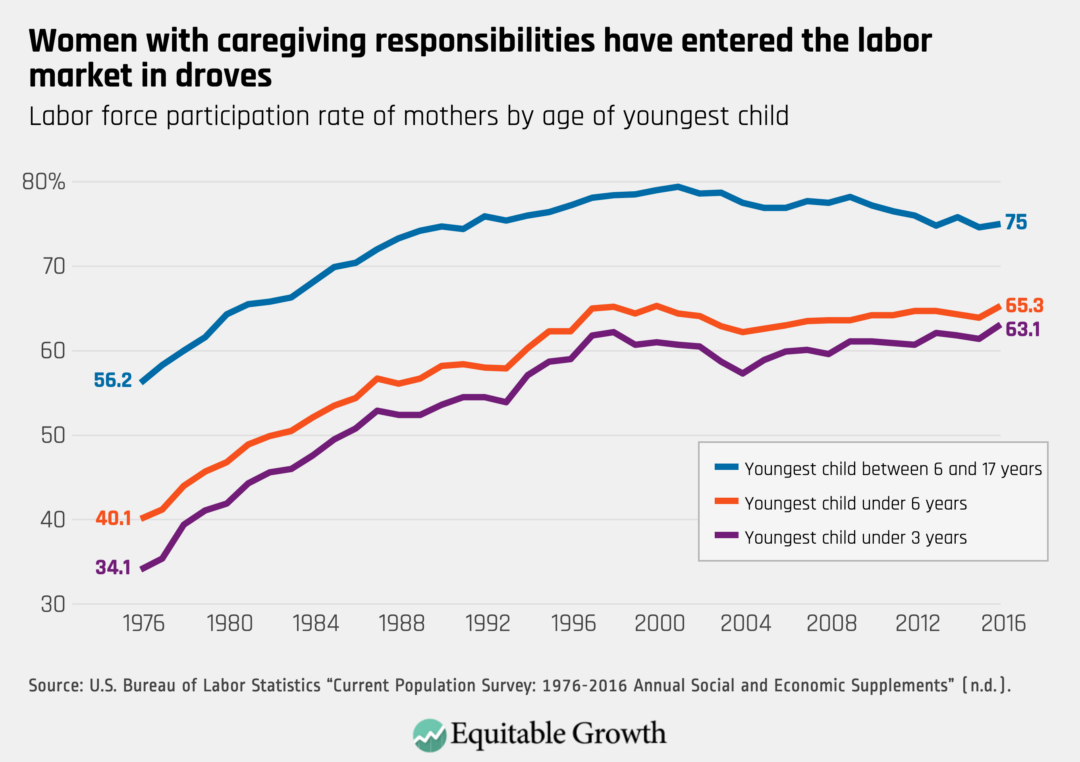

Differences in the labor force participation of mothers exemplifies this paradox. While maternal labor force participation has increased since the 1970s, participation rates are lower for mothers with younger children. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Younger children generally require more intensive care and staff time, and as a result, child care for this age group is pricier than for older children. In 2019, the average annual price of center-based care was between $11,444 and $11,896 for infants and between $9,043 and $9,254 for 4-year-old children.15These high prices, in the absence of subsidies or other discounts, can force working parents to find lower-cost informal care, either with family, a friend, a neighbor, or an unlicensed provider—even if it is not the family’s preferred or the most stable option—or start making hard choices about their own employment arrangements.

Accessible and affordable child care can reduce this care-work conflict for families. Research by Taryn Morrissey at American University and by Chris Herbst at Arizona State University and Burt Barnow of George Washington University suggests that when child care is affordable and geographically accessible, parents, particularly mothers, are more likely to enter or reenter the workforce.16 In fact, economists have long demonstrated that when the price of child care decreases, maternal employment increases.

In one economic model, for example, fully subsidizing child care costs so that parents paid nothing rather than an average of $89 per week (in 2021 dollars) increased the rate of maternal employment from 37 percent to 87 percent.17 The exact relationship between child care costs and maternal employment varies across studies, with researchers typically finding that a 10 percent reduction in child care costs increases maternal employment by 0.25 percent to 11 percent.

Recent U.S.-based research suggests more modest, but still significant, associations between child care costs and maternal employment.18 While researchers are still examining the exact magnitude of the price-employment relationship, the direction of that relationship is clear: When child care is less expensive, parents participate in the labor force at a higher rate. Intuitively, these gains are generally strongest among women with young children.19

Affordability of care clearly affects parental labor supply, but accessibility is an important consideration as well. Child care could be free, but if families can’t use that care because of where it is located, the hours it is available, the language spoken by care providers, or the accommodations available to their children, then their child care challenges remain unsolved.

A 2018 analysis by the Center for American Progress estimated that half of U.S. families live in so-called child care deserts, census tracts where there are three or more children under age 5 for each licensed child care slot.20 Families in these deserts must compete for limited slots, travel long distances to licensed care, rely on informal or unlicensed care, or forgo work in order to stay home and care for their children. So, it’s not a surprise that a 2007 study using data from Maryland finds that when the geographic supply of care increases, so does the labor supply across the community for all women.21

When accessibility is a challenge, finding new child care arrangements when initial child care plans fall through can be particularly difficult, potentially pulling parents out of the labor force. A 2008 study of mothers in low-wage jobs found that 19 percent stopped work entirely in the same quarter in which they experienced a disruption to their child care arrangements, compared to only 9 percent who did not experience such a provider disruption.22

Employers who worry about employees not having stable access to child care discriminate against parents in their hiring decisions, which makes securing employment even more difficult for people with children.23 In particular, researchers have identified a persistent “motherhood penalty” in employers’ hiring decisions, in which mothers, but not fathers, are perceived to be less competent and committed to their work, resulting in fewer opportunities and lower wages for women.24

Facilitating greater labor force participation among mothers may be a source of significant economic growth in the United States due to stagnation in women’s labor force participation growth rates in recent decades and, most recently, the decline in their workforce engagement amid the coronavirus pandemic. Greater labor force participation results in greater household economic security, greater consumer spending, and a larger tax base to fund productive government expenditures—such as infrastructure and education investments—that can all contribute to economic growth.25

In one recent estimate, increased employment due to accessible, affordable care was predicted to, over the course of a lifetime, increase a mother of two’s earnings by about $94,000, leading to an additional $20,000 in savings and $10,000 in Social Security benefits.26 But without accessible and affordable child care options, too many parents will remain outside of the workforce, and greater economic gains will remain unrealized.

Stable child care supports businesses with a more reliable and productive workforce

While the literature on the growth potential of child care primarily focuses on the perspectives of families, there is evidence that employers stand to gain from greater access to accessible and affordable child care as well. When children are sick and can’t attend their care arrangements, or the care providers themselves are sick, closed, or otherwise unable to look after children on short notice, working parents may be unable to report for their regular shifts, or their concern for their child’s well-being may distract them and decrease their productivity when they do report to work. Disruptions in child care arrangements can thus reduce worker productivity, lead to staffing challenges, and harm businesses’ bottom line.

When parents are unable to report to work due to child care concerns—which is sometimes referred to as absenteeism—then they may lose out on a day’s pay, and their employers lose out on a day of productivity, or even more. Research suggests that workers with high absence rates are more likely to report high productivity losses when they are back at work.27

Even when parents dealing with child care disruptions do report to work on time, they may be distracted finding a care solution and also are less productive—a phenomenon known as presenteeism.28 Recent research on presenteeism, conducted primarily in the context of worker illness, shows significant and costly productivity losses for employers.29 Helping workers avoid or manage these disruptions, therefore, should be a priority for employers, as well as policymakers.

Employers may be more likely to offer and advertise child care solutions for their high-wage workers, but productivity gains may be the greatest when low-wage workers are provided with adequate care options.30 Research shows that disruptions to child care are more common among lower-income mothers, while mothers with more resources, including higher income and education levels, tend to have an easier time locating backup care.31 While the social networks that highly resourced parents can access may play a role in this disparity, lower-income mothers are also less likely to have access to family-friendly work policies, such as on-site child care, sick leave, and flexible and predictable work schedules that can help smooth the disruptions caused by interruptions in care arrangements.32 Access to such family-friendly policies, in addition to dependable child care options in families’ local communities, can help mitigate these challenges and the potential productivity loss from unstable care.

Early care and education supports long-term economic growth

High-quality care helps children develop their human capital, the key to long-term U.S. economic growth. The research in the prior section of this report demonstrates that stable, accessible, and affordable child care can lead to short-term economic growth through increases in parental employment and reduced absenteeism/presenteeism. Additionally, high-quality early care and education has the potential for long-term economic growth, as the young children receiving care develop their human capital preparing for school and beyond.

Traditional child care and early learning programs, such as pre-Kindergarten programs and Head Start, have long been considered separate services for families. But no matter where a child is cared for, many of the ingredients for high-quality and stimulating care are the same. As the ongoing coronavirus pandemic makes clear, early learning and school is a form of child care, and child care is a place for learning and development. Completely separating the two is not possible.

Both so-called universal care and targeted care (see sidebar) provide socialization and learning opportunities that are critically important in the early childhood years, a time when the brain is developing rapidly and is particularly responsive to the outside environment.33 When children are cared for in a supportive, nurturing environment, either by family members or professionals, there are physical changes in their brain development associated with positive long-term outcomes. High-quality, positive caregiving can even mitigate harmful developmental outcomes associated with poverty and high-stress environments, suggesting an important role for early care and education in addressing inequality and the intergenerational cycle of poverty.34

Over the years, a robust literature evaluating the effects of early care and education programs—primarily focused on formal pre-K initiatives—finds evidence of positive developmental, education, social, and economic outcomes among participants. In several evaluations of Tulsa, Oklahoma’s universal pre-K program, researchers found that the experiences and lessons learned in the program translated to enhanced school readiness. Participants in that Tulsa program scored better than their peers on standardized measures of reading, spelling, math, and problem-solving skills.35 Many of these effects were still discernable at least through the students’ time in middle school.36

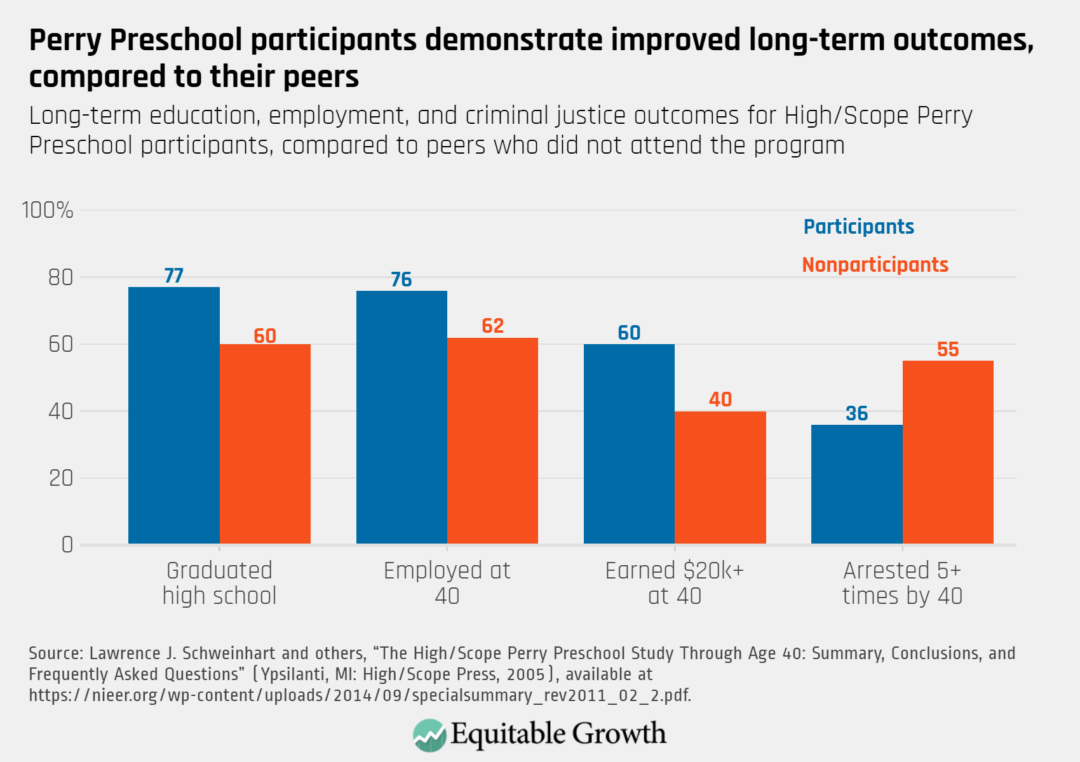

Likewise, participants in the famous Perry Preschool program, a 2-year targeted early care and education intervention for low-income Black children, also presented higher test scores and school readiness in the years following the program.37And for both intensive, targeted programs, such as Perry Preschool and Head Start, and universal programs, such as the Tulsa pre-K system, improvements in school readiness were robust across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic categories, further adding to the evidence that high-quality early care and education can potentially mediate the harmful effects of inequality.38

These effects also are likely to persist in the long term.39 In a follow up to the original 1960s Perry Preschool study, when former students were 40 years old, past participants were significantly more likely to be employed, high school graduates, and earning more than their peers who did not complete the program. They also experienced significantly less involvement with the criminal justice system.40 (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

A more recent 2021 evaluation of a universal pre-K program in Boston, Massachusetts took advantage of the program’s random lottery enrollment system to provide strong evidence on its long-term effects. Like the more targeted Perry Preschool program, participants in Boston’s universal preschools were more likely to graduate from high school by 6 percentage points, complete the SATs by 9 percentage points, and enroll in college on time by 8 percentage points, compared to similarly aged peers not selected through the city’s lottery system. Participants were also less likely to experience high school suspensions and involvement in the juvenile justice system.41

In helping children avoid negatives experiences with high economic costs—such as getting pulled into the criminal justice system—and experience positive outcomes associated with higher economic gains—including high school graduation and college enrollment—the research literature provides a clear mechanism by which high-quality child care and pre-K programs would be expected to boost workers’ earnings and our nation’s economic growth. Other factors—including the impact of pervasive structural racism and the ebbs and flows of the business cycle—can negatively impact one’s lifetime economic trajectory. But the long-term research strongly suggests that kids who get started in a high-quality early care and education program may be better positioned to weather these challenge as they grow into tomorrow’s breadwinners and parents themselves.

There are multiple beneficiaries from this positive relationship between child care and employment. Families of the future earn higher incomes and experience greater economic stability. The broader economy benefits from higher consumer spending. And businesses enjoy a larger, better-educated, and more skilled labor force from which to draw employees.

Reaping benefits for the macroeconomy through robust investment in care

A growing research base shows the economic potential of high-quality child care and pre-K programs. Various estimates by early childhood researchers and economists suggest that every dollar spent on early care and education initiatives generates $8.60 in economic activity in the long term, primarily through the increased earnings of care participants.42 Yet the United States does not have an early care and education system capable of delivering these benefits on a large scale. The failure to realize this potential is no accident: It is the result of decades of policy decisions that treat child care as a personal responsibility that can be met by the private market, despite decades of evidence that this is a failed strategy for families.

Greater public investment in early care and education offers multiple benefits. It can reduce the out-of-pocket spending for families, helping parents who wish to work outside of the home to do so. It also reduces the child care industry’s exposure to macroeconomic conditions, ensuring that child care remains an available support to families in recessions, as well as periods of stronger growth. Finally, greater public investment can increase the supply of high-quality care—key to human capital development and long-term economic growth.

Increased public investment can offset deficiencies in the private market

Research in the previous two sections of this report demonstrates that accessible, affordable, and high-quality child care can contribute to short- and long-term economic growth. For many of the long-term benefits discussed—cognitive development, school readiness, and better economic, educational, and social outcomes in the future—quality is the key ingredient, particularly for children from disadvantaged households.43

But care costs money, with one significant expense being a well-trained and educated workforce that requires fair compensation, and high-quality care costs even more. Yet private purchasers of child care—families or their employers—often don’t have room in their budgets for high-quality care or, indeed, for any care at all.44

Increasing public spending to account for the cost of quality and to increase the scale of care provision is critical to help the economy realize the growth potential of early care and education. This is the general model of the primary and secondary public education system in the United States. Communities have long recognized the long-term benefits of a better-educated public and devoted public dollars to finance basic K-12 education for all children.45

As with the nation’s K-12 system, early care and education delivers public benefits that far offset the costs, yet the private child care market is ill-positioned to recognize these public benefits and provide the quality and quantity of care that would be socially and economically optimal.

There is already evidence that existing public investment in early care and education can yield promising outcomes, but overall public investment remains too low and too limited to a subset of low-income families. Communities with universal public pre-K education, including the District of Columbia, West Virginia, Oklahoma, and elsewhere, are already enjoying higher early education enrollment and long-term social and economic benefits, but the availability of universal pre-K is geographically limited and still unavailable to millions of families.

Robust subsidies ensure families can afford the care they need and contribute to the labor force when they choose

Reliable and robust public spending can lower the out-of-pocket costs for families to purchase care, thus reducing the costs parents must pay in order to engage in work. Currently, child care subsidies represent the chief mechanism for public child care investment in the United States. The main source of child care assistance is the federal Child Care and Development Block Grant program, which provides funding to states to help families afford care, as well as to invest in improving the quality of care.

Several decades of academic research demonstrates a significant association between access to child care subsidies—which decrease families’ child care costs—and increased labor force participation, hours worked, and wages among mothers.46 These results generally hold across family structure and income level.

In one 2020 study, for example, a 10 percent increase in child care subsidies was associated with a 2 percent increase in employment among married mothers, while prior research indicates that a $100 increase in block grant subsidies would be expected to increase employment among single mothers by 2 percentage points.47These findings are perhaps unsurprising, given the related literature on the costs of child care and maternal labor force participation. The findings are nonetheless encouraging in that they show that the public policy mechanisms already in place can be effective in reducing costs and increasing employment.

Despite this promising research, too few families can access the child care subsidies they need to purchase appropriate care and engage in the workforce. In recent years, the U.S. Congress has significantly increased funding for the Child Care and Development Block Grant. Even so, annual funding remains below its peak in the early 2000s, adjusted for inflation and excluding COVID-19 emergency relief funding. And the number of families receiving subsidies has declined even as the eligible population grows.

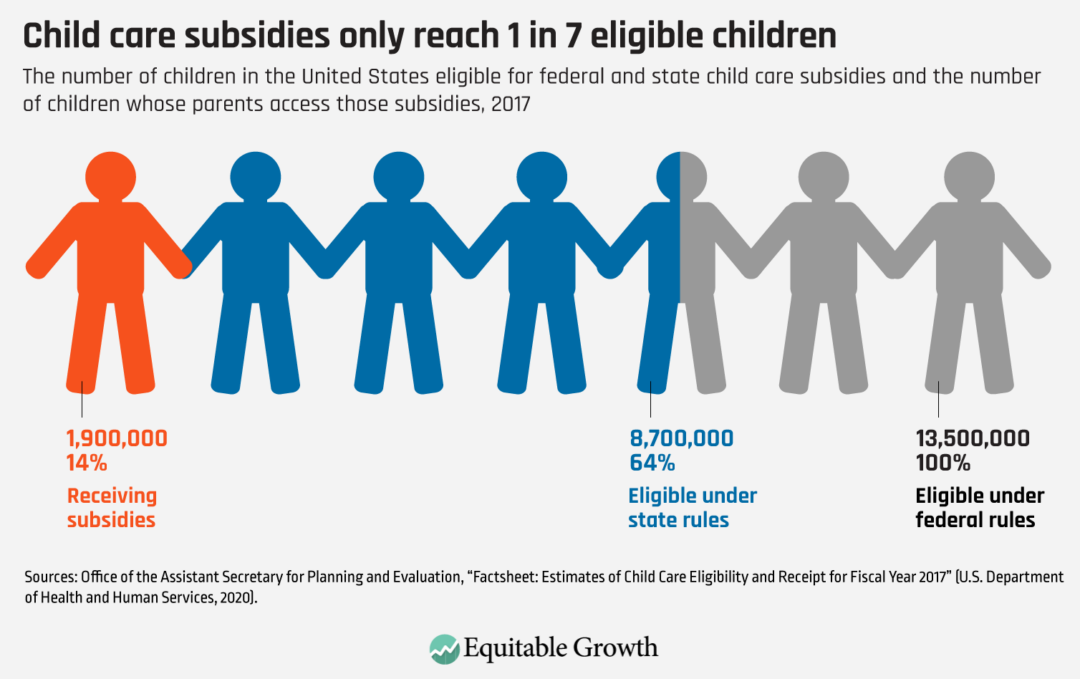

To contend with there being a greater need than there are available subsidies, some states limit access by setting lower income thresholds far below the maximum allowed under federal law, set other restrictive eligibility criteria, institute wait lists, and/or simply fail to provide outreach to let families know that help is available. A recent report by the Government Accountability Office, the nonpartisan investigative arm of the U.S. Congress, estimates that in 2017, 13.5 million children ages 0 to 12 were eligible for subsidies under federal rules and 8.7 million were eligible under state rules, but only 1.9 million children actually received subsidies for their child care.48 (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Fully funding child care subsidies to support all low-income families and expanding eligibility for those in middle- or higher-income brackets is critical to inducing parental labor force participation and economic growth in the short term.

Stable public funding ensures child care is available to support families and macroeconomic growth

Currently, the early care and education system in the United States is chiefly funded through parent fees, meaning out-of-pocket tuition payments by families enrolling their children in care. As stated above, the sticker price of child care—whether in center- or home-based settings—can be exorbitant. Some families may have the economic means to pay these prices for their child care needs, but many more will be unable or unwilling and will instead seek out alternative arrangements.

Research shows that when the cost of formal care rises, families transition to informal or family-based care arrangements and may even forgo work to care for their children at home.49 In other words, when families’ economic conditions or child care prices change, so too do their decisions on the types and amount of care to purchase. This can lead to financial instability for formal providers unable to compete with the informal market on prices.

Reliance of parent fees leaves the child care market particularly exposed to broader economic trends. When parents are laid off, they often can no longer afford child care and may pull their children from care. Because profit margins are so thin, if just a few parents pull their children from care, then the child care provider may need to lay off staff—or even temporarily suspend operations entirely—to stay in the black.

Recent research demonstrates how this exposure is both significant and asymmetrical: Every 1 percent decline in a state’s overall employment is associated with a 1.04 percent decline in child care employment, but every 1 percent increase in a state’s overall employment is only associated with a 0.75 percent increase in child care employment.50 Even when the economy is in recovery and newly employed parents wish to enroll their children back in care, there are inherent delays while the child care industry rebuilds capacity lost during weaker economic times.

To put it another way, when the economy is in decline, child care declines faster, but when the economy is in recovery, child care recovers slower. This can cause a dangerous drag on growth as economic declines damage a child care market that is essential for allowing labor force participation and economic recovery. Therefore, an overreliance on parent fees for child care poses risks not just to families and care providers, but also to the economy overall.

Increasing public financing for child care can help blunt this trend. Research shows that public investment helped care providers weather the economic turmoil unleashed by the coronavirus pandemic and recession. Child care programs that received public funding, rather than solely relying on parental fees, were better able to retain their enrollment and staff during the coronavirus recession.51

In that respect, the pandemic experience of these programs with public funding was similar, albeit not as stable, as that of publicly funded K-12 education systems. Despite temporary closures and changes in enrollment, parents could be generally confident that their local public schools would still be there when it was time for their child to return in person. The same could not be said for their privately funded child care providers.

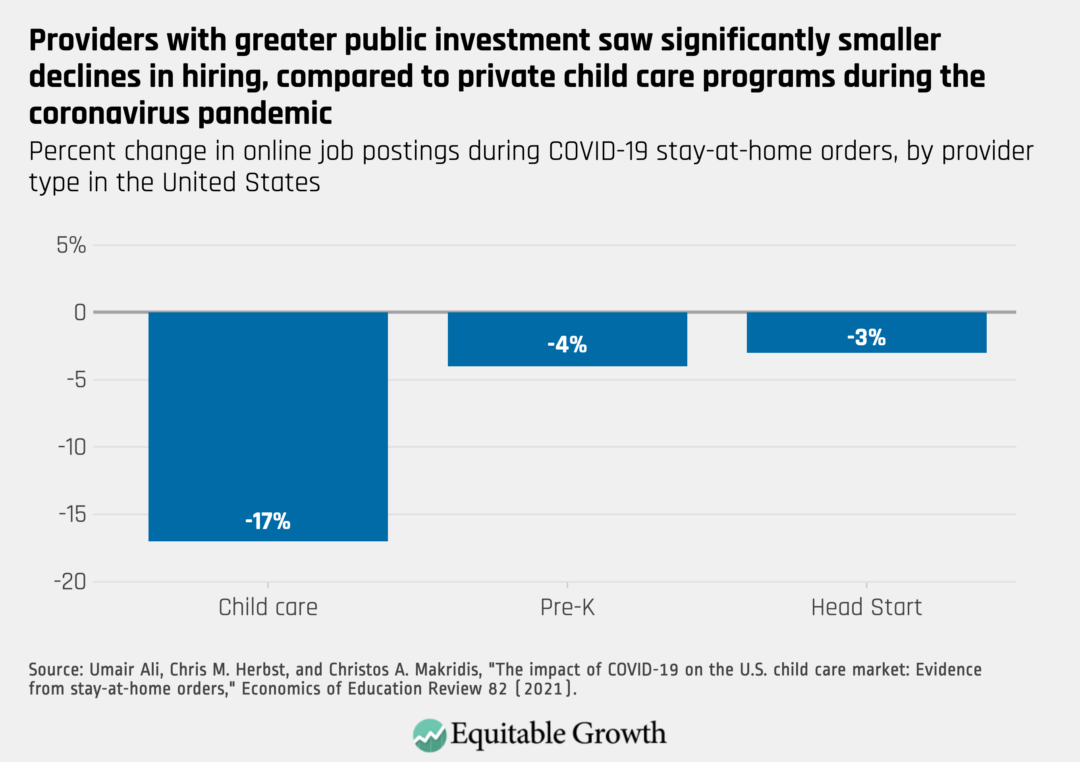

Even during the most restrictive periods of the pandemic, when multiple states had stay-at-home orders in place, pre-K and Head Start programs benefited from the stability offered by public investment and were able to largely maintain pre-pandemic hiring plans. Conversely, child care systems that primarily rely on parental fees saw a more significant decline in hiring during that period.52 This slowdown in hiring contributed to a significant contraction in the child care workforce in the early months of the pandemic that was sustained through 2021. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

Adequate funding and caregiver support is necessary for quality caregiving and improved human capital development

Subsidies are important, but they alone are not the silver bullet that will fix the child care crisis in the United States. While many studies find a positive relationship between parents receiving subsidies and maternal employment outcomes, the literature on subsidies as they relate to the quality of care—a critical ingredient for long-term growth—is more mixed.

In some studies, parents receiving subsidies are more likely to purchase formal care, select care that is higher-rated on measures of language, cognitive, and social growth, and be more satisfied with the care they use overall.53 Yet similar studies find little direct evidence between existing subsidies themselves and enhanced childhood development and academic achievement, particularly among lower-incomes families.54 Put simply, the U.S. subsidy system is not paying for quality in child care, so parents and the nation get what we pay for.

The current subsidy system is not sufficient in supporting the type of care that fosters children’s human capital development for two primary reasons. First, subsidy amounts are generally low, primarily covering the cost of workers’ low salaries and leaving insufficient funds for providers to meaningfully invest in the activities and materials that promote quality caregiving and improved human capital development.55

Second, when the Child Care and Development Block Grant was reauthorized by Congress in 2014, it included new quality and safety standards that providers must meet to qualify to receive child care subsidies. These requirements are critical in ensuring children are safe and families can be confident in the quality of care their children receive. Unfortunately, Congress did not allocate sufficient funds to assist all providers in meeting these standards.

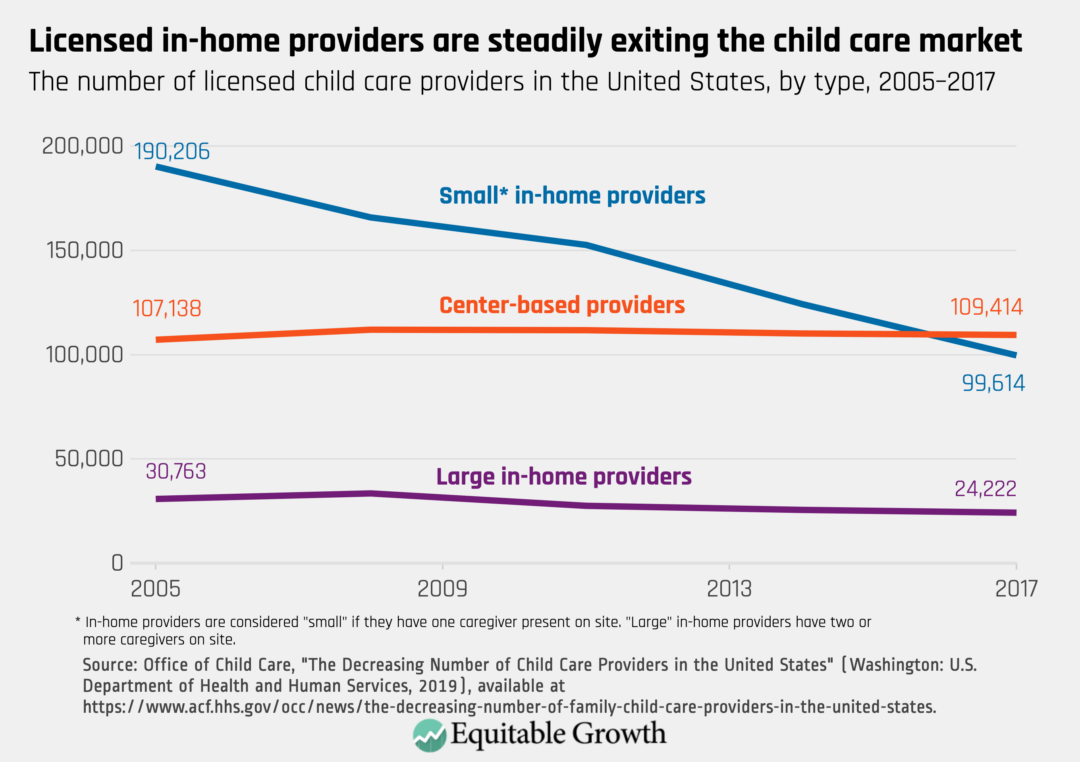

As a result, many smaller providers, particularly in the home-based sector, continue to struggle without additional support.56 These providers were already dealing with low pay and poor working conditions, contributing to a decades-long decline in the number of licensed home-based providers.57 Whether these licensed providers are exiting the market completely or transitioning to the underground, unregulated market, the results are the same: fewer subsidy-eligible providers in whom families can be confident in the quality of care their children receive. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

Fully funding the Child Care and Development Block Grant so that providers can receive subsidies in line with the cost of high-quality care is one way in which greater public investment could increase the availability and quality of child care for working families. Another is devoting resources for state-level agencies to assist providers in qualifying for subsidies.

Additionally, regulators and social service agencies at the federal, state, and local levels should invest money and manpower so that all child care providers—including small independent child care centers, licensed family child care homes, and so-called family, friend, and neighbor, or FFN, providers—have the resources and guidance they need to meet any requirements and navigate the process to receive subsidies if they choose to do so. Such supports would raise quality across provider types and ensure a range of child care options to meet families’ varied needs.

But public investment also must come in the form of targeted funds and initiatives designed to raise quality standards for all children and providers, not just those entwined with the subsidy system.58 Supporting child care workers is central to promoting quality caregiving and improved human capital development.

One factor that researchers have pegged as particularly meaningful to quality is caregivers’ qualifications and training.59 Some promising methods for supporting the early education workforce while raising quality and worker pay in the process include:

- Providing programmatic support and funding for improved preparatory training programs for providers

- Internship and student teaching opportunities

- Professional development opportunities

- Coaching, consultations, and mentoring60

Most importantly, however, is the need to financially support the workers that care for our nation’s children. The child care workforce is one of the lowest paid in the U.S. economy, contributing toward high turnover in the profession—and high stress among those providers who remain in the field. All of these baleful outcomes undermine the quality of care children receive. With a median hourly salary of $12.88—or $26,790 per year—many child care workers lack economic security and stability for their own families.61 Using public funds to support fair compensation would help reverse the decades-long undervaluing of these workers’ labor, promote spending and saving in their own households, and, importantly, stabilize the workforce by ensuring that these workers can afford to stay in their jobs.62

Greater public investment could spur economic growth, offsetting short-term costs

Greater public investment in the child care market is necessary for the United States to unlock the full growth potential of an accessible, affordable, and high-quality early care and education system. Meaningful public investment in child care should have the goals of:

- Promoting family economic security through a combination of employment participation and lower costs

- Stabilizing the precarious child care market, thus ensuring adequate supply of care in communities with the most need

- Supporting high-quality care by assisting providers in meeting licensing standards, providing targeted training and professional development support for workers, and fairly compensating workers so that they can support their own families and remain in their careers

Economic theory and empirical evidence reinforce that early care and education remains a smart investment. Research on public financing and how nations achieve economic growth in the long term continuously point toward the importance of investing in human capital.63 After all, it is people who develop the products, processes, services, and technologies that translate to a more productive and efficient economy. Recent public finance models suggest that human capital spending in the long term is one of the most effective ways in which government spending is translated into an economy’s well-being and should therefore be a priority for policymakers who seek to spur economic growth.64

In other words, investing in people is often a safe bet, and investing in the nation’s children is one of the safest bets policymakers can make. As documented above, research on both targeted and universal early care and education programs find significant internal rates of return: Economies can earn approximately $8.60 for every dollar invested in the long run.65

Making the necessary investments to actualize these returns will involve a greater commitment from the public to supporting the child care market. But doing so would be a commitment that should pay off handsomely for the nation and the economy.

Growth that is strong, stable, and broadly shared will only be achieved by making choices that prioritize robust public investments in people and communities and sustain the workers and families who are the foundation of our economy. High-quality early care and education is worth the cost, and now, with the cost of borrowing at record lows, policymakers can prioritize investments in the nation’s care infrastructure at an effective discount, further accentuating the short- and long-term economic benefits from an accessible, affordable, and high-quality child care system.66

Conclusion

The intentional neglect that policymakers in the United States have inflicted on the early care and education market is preventing the U.S. economy from reaching its full potential. The country loses a competitive advantage as growth in mothers’ labor force participation stagnates and labor force participation for all women falls below peer nations. Children in our country are missing out on important educational and developmental opportunities when the quality of care is too low.

The research evidence also strongly suggests that a more accessible, affordable, and high-quality early care and education system can reverse these trends by inducing women’s entry into the labor force in the short term and promoting critical human capital development in the long term.

The short- and long-term economic potential of early care and education suggests tremendous benefits from these programs to the general public. These benefits tend to spill out of the private market and into the public sphere, but the private market is unlikely to purchase the quantity and quality of child care that would yield the most economic growth.

Enhanced, targeted public investment can correct for these deficiencies in the private market by reducing out-of-pocket costs for families, stabilizing the supply of care, and raising the level of quality across care types. By making these investments, the economy stands to enjoy a significant rate of return—approximately $8.60 in benefits for every $1 in costs.67

Working U.S. families should not have to struggle to find safe, convenient, and high-quality care options for their children. By neglecting the child care market for decades, policymakers have shifted the burden of child care onto the shoulders of families already bearing the weight of child-rearing, employment, and other responsibilities at home—despite research evidence that the public has the most to gain from a functional and equitable child care system.

Addressing the child care crisis has the potential to improve families’ economic security and well-being while accelerating economic growth in the short and long term. To do so, policymakers must unburden families with meaningful, targeted, and evidence-based investments in the nation’s early care and education system. The alternative—continuing to neglect this crisis in care—could be too costly to bear.

About the author

Sam Abbott is a family economic security policy analyst at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

Acknowledgments

The Washington Center for Equitable Growth would like to thank the researchers, scholars, and policy experts who participated in the September 2020 research convening, “Kick-off Roundtable on Accessible and Affordable Child Care.” Their scholarship, insight, and experiences informed the content of this report. Additionally, special thanks is owed to Rasheed Malik, Laura McSorley, Taryn Morrissey, Melissa Boteach, Karen Schulman, and Whitney Pesek for their assistance, review, and feedback on drafts of this report.

End Notes

1. Heather Boushey, Finding Time: The Economics of Work-Life Conflict (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016), pp. 101–102, with a synopsis available at https://equitablegrowth.org/finding-time/.

2. Elliot Haspel, Crawling Behind: America’s Childcare Crisis and How to Fix It (Castroville: Black Rose Writing, 2019), 50, with a synopsis available at https://www.capita.org/capita-ideas/2019/11/11/crawling-behind-americas-childcare-crisis-and-how-to-fix-it.

3. Economic Policy Institute, “The Cost of Child Care in the United States” (2020), available at https://www.epi.org/child-care-costs-in-the-united-states/.

4. Richard Nixon, Veto Message—Economic Opportunity Amendments of 1971, 92nd Cong. 1st sess. (December 10, 1971), available at https://www.senate.gov/legislative/vetoes/messages/NixonR/S2007-Sdoc-92-48.pdf, as cited in Elizabeth Palley and Corey S. Shdaimah, In Our Hands: The Struggle for U.S. Child Care Policy (New York: New York University Press, 2014), pp. 50–51.

5. Meredith Johnson Harbach, “Childcare Market Failure,” Utah Law Review 2015 (3): 659–719, available at https://scholarship.richmond.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=2151&context=law-faculty-publications.

6. Ajay Chaundry and others, Cradle to Kindergarten: A New Plan to Combat Inequality, 2nd ed. (New York: The Russell Sage Foundation, 2021), pp. 41–69.

7. Boushey, Finding Time: The Economics of Work-Life Conflict, pp. 86–87.

8. Timothy Grall, “Custodial Mothers and Fathers and Their Child Support: 2015” (Washington: U.S. Census Bureau, 2020), available at https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p60-262.pdf.

9. Jeanna Smialek, “Powell Says Better Child Care Policies Might Lift Women in Work Force,” The New York Times, February 24, 2021, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/24/business/economy/fed-powell-child-care.html.

10. Charles M. Kalenkoski, David C. Ribar, and Leslie S. Stratton, “The effects of family structure on parents’ child care time in the United States and the United Kingdom,” Review of Economics of the Household 5 (4) (2007), available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11150-007-9017-y.

11. Sara Raley, Suzanne M. Bianchi, and Wendy Wang, “When Do Fathers Care? Mothers’ Economic Contributions and Fathers’ Involvement in Child Care,” American Journal of Sociology 117 (5) (2012), available at https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/663354.

12. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Women in the labor force: a databook (U.S. Department of Labor, 2021), available at https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-databook/2020/home.htm.

13. Ozlem Tasseven, “The relationship between economic development and female labor force participation rate: A panel data analysis.” In Ü. Hacioğlu and H. Dinçer, eds., Global Financial Crisis and Its Ramifications on Capital Markets (Basel, Switzerland: Springer, Cham, 2017), available at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47021-4_38.

14. Mark Lino and others, “Expenditures on Children by Families, 2015”(Alexandria: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2017), available at https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/crc2015_March2017_0.pdf.

15. Child Care Aware of America, “The US and the High Price of Child Care: An Examination of a Broken System” (2019), available at https://www.childcareaware.org/our-issues/research/the-us-and-the-high-price-of-child-care-2019/.

16. Taryn Morrissey, “Child Care and Parent Labor Force Participation: A Review of the Research Literature,” Review of Economics of the Household 15 (1) (2017): 1–24, available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11150-016-9331-3; Chris M. Herbst and Burt S. Barnow, “Close to Home: A Simultaneous Equations Model of the Relationship Between Child Care Accessibility and Female Labor Force Participation,” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 29 (2008): 128–151, available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-007-9092-5.

17. David M. Blau and Philip K. Robins, “Child-Care Costs and Family Labor Supply,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 70 (3) (1988), available at http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0034-6535%28198808%2970%3A3%3C374%3ACCAFLS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-3.

18. Morrissey, “Child Care and Parent Labor Force Participation: A Review of the Research Literature.”

19. Ibid.

20. Rasheed Malik and others, “America’s Child Care Deserts in 2018” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2018), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/reports/2018/12/06/461643/americas-child-care-deserts-2018/.

21. Herbst and Barnow, “Close to Home: A Simultaneous Equations Model of the Relationship Between Child Care Accessibility and Female Labor Force Participation.”

22. Rachel A. Gordon, Robert Kaestnery, and Sanders Korenman, “Child Care and Work Absences: Trade-Offs by Type of Care,” Journal of Family and Marriage 70 (1) (2008), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/40056266?seq=1.

23. Deniz S. Ones, Chockalingam Viswesvaran, and Frank L. Schmidt, “Personality and Absenteeism: A Meta-Analysis of Integrity Tests,” European Journal of Personality 17 (2003), available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1002/per.487?journalCode=erpa.

24. Shelley J. Correll, Stephen Benard, and In Paik, “Getting a Job: Is There a Motherhood Penalty?” American Journal of Sociology 112 (5) (2007), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/511799?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

25. Rachel Conelly and Jean Kimmel, “The Effect of Child Care Costs on the Employment and Welfare Recipiency of Single Mothers,” Southern Economic Journal 69 (3) (2003), available at https://www.people.vcu.edu/~lrazzolini/GR2003.pdf; Gerhard Glomm and B. Ravikumar, “Productive government expenditures and long-run growth,” Journal of Economic Dynamics and Controls 22 (1) (1997), available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0165188995009299; Konstantinos Angelpoulos, George Economides, and Pantelis Kammas, “Tax-spending policies and economic growth: Theoretical predictions and evidence from the OECD,” European Journal of Political Economy 23 (4) (2006), available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0176268006001182.

26. Robert Paul Hartley and others, “A Lifetime’s Worth of Benefits: The Effects of Affordable, High-quality Child Care on Family Income, the Gender Earnings Gap, and Women’s Retirement Security” (Washington: National Women’s Law Center, 2021), available at https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/A-Lifetimes-Worth-of-Benefits-_FD.pdf.

27. Nicole A. Maestas, Kathleen J. Mullen, and Stephanie Rennane, “Absenteeism and Presenteeism Among American Workers,” Journal of Disability Policy Studies 32 (1) (2020), available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1044207320933211.

28. While presenteeism typically refers to an employee reporting to work while ill, some scholars adopt a more expansive definition to include reporting for work while experiencing any event that would otherwise compel an absence. For a review of presenteeism and it’s definition, see Gary Johns, “Presenteeism in the workplace: A review and research agenda,” Journal of Organizational Behavior 31 (4) (2010), available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/job.630.

29. Paul Hemp, “Presenteeism: At Work—But Out of It,” Harvard Business Review 82 (10) (2004): 49–58, available at https://hbr.org/2004/10/presenteeism-at-work-but-out-of-it.

30. Taryn W. Morrissey and Mildred E. Warner, “Employer-Supported Child Care: Who Participates?” Journal of Marriage and Family 71 (5) (2009), available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00672.x.

31. Margaret L. Usdansky and Douglas A. Wolf, “When Child Care Breaks Down: Mothers’ Experiences with Child Care Problems and Resulting Missing Work,” Journal of Family Issues 29 (9) (2008), available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0192513X08317045.

32. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2020 (U.S. Department of Labor, 2020), available at https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2020/employee-benefits-in-the-united-states-march-2020.pdf.

33. Neal Halfon, Ericka Shulman, and Miles Hochstein, “Brain Development in Early Childhood. Building Community Systems for Young Children” (Los Angeles: University of California Center for Healthier Children, Families, and Community, 2001), available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED467320.pdf.

34. James J. Heckman, “Skill Formation and the Economics of Investing in Disadvantaged Children,” Science 312 (2006), available at https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.323.3102&rep=rep1&type=pdf; Joan Luby, Andy Belden, and Kelly Botteron, “The Effects of Poverty on Childhood Brain Development: The Mediating Effect of Caregiving and Stressful Life Events,” JAMA Pediatrics 162 (12) (2013), available at https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/1761544.

35. William T. Gormley Jr. and others, “The Effects of Universal Pre-K on Cognitive Development,” Developmental Psychology 41 (6) (2005), available at https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/dev-416872.pdf.

36. William T. Gormley Jr., Deborah Phillips, and Sara Anderson, “The Effects of Tulsa’s Pre-K Program on Middle School Student Performance,” The Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 37 (1) (2018), available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/pam.22023.

37. Lawrence J. Schweinhart and others, “The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study Through Age 40: Summary, Conclusions, and Frequently Asked Questions” (Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Press, 2005), available at https://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/specialsummary_rev2011_02_2.pdf.

38. William T. Gormley Jr., “The Effects of Oklahoma’s Pre-K Program on Hispanic Children,” Social Science Quarterly 89 (4) (2008), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/42956353?seq=1; Heckman, “Skill Formation and the Economics of Investing in Disadvantaged Children.”

39. Taryn Morrissey, Lindsey Hutchinson, and Kimberly Burgess, “The Short- and Long-Term Impacts of Large Public Early Care and Education Programs” (Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014), available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/180301/rb_longTermImpact.pdf.

40. Schweinhart and others, “The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study Through Age 40.”

41. Guthrie Gray-Lobe, Parag A. Pathak, and Christopher R. Walters, “The Long-Term Effects of Universal Preschool in Boston.” Working Paper 28756 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021), available at http://www.nber.org/papers/w28756.

42. Executive Office of the President, The Economics of Early Childhood Investments (2015), available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/early_childhood_report_update_final_non-embargo.pdf.

43. Ellen S. Peisner-Feinberg and Margaret R. Burchinal, “Relations Between Preschool Children’s Child-Care Experiences and Concurrent Development: The Cost, Quality, and Outcomes Study,” Merrill-Palmer Quarterly 43 (3) (1997), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/23093333?seq=1; Elizabeth Votruba-Drzal, Rebekah Levin Coley, and P. Lindsay Chase-Lansdale, “Child Care and Low-Income Children’s Development: Direct and Moderated Effects,” Child Development 75 (1) (2004), available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15015691/; Ellen S. Peisney-Feinberg, “Child Care and Its Impact on Young Children’s Development.” In Encyclopedia of Early Childhood Development, 2nd ed. (2007), available at https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.484.7891&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

44. Haspel, Crawling Behind: America’s Childcare Crisis and How to Fix It; David M. Blau, The Child Care Problem: An Economic Analysis (New York: The Russel Sage Foundation, 2001); Erin J. Maher, Becki Frestedt, and Cathy Grace, “Differences in Child Care Quality in Rural and Non-Rural Areas,” Journal of Research on Rural Education 24 (4) (2008), available at https://jrre.psu.edu/sites/default/files/2019-08/23-4.pdf.

45. W.W. McMahon, “The External Benefits of Education.” In International Encyclopedia of Education, 3rd ed. (Amsterdam: Elsevier Science, 2010), available at https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.01226-4; Claudia Golden, “A Brief History of Education in the United States.” Historical Paper 119 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 1999), available at https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/h0119/h0119.pdf.

46. For examples, see Blau and Robins, “Child-Care Costs and Family Labor Supply”; Marc C. Berger and Dan A. Black, “Child Care Subsidies, Quality of Care, and the Labor Supply of Low-Income, Single Mothers,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 74 (4) (1992), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/2109377?seq=1; Pierre Lefebvre and Philip Merrigan, “Child-Care Policy and the Labor Supply of Mothers with Young Children: A Natural Experiment from Canada,” Journal of Labor Economics 26 (3) (2008), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/587760?seq=1.

47. Gabrielle Pepin, “The Effects of Child Care Subsidies on Paid Child Care Participation and Labor market Outcomes: Evidence from the Child and Development Care Credit.” Working Paper 20-331(W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2020), available at https://research.upjohn.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1350&context=up_workingpapers; Chris M. Herbst, “The labor supply effects of child care costs and wages in the presence of subsidies and the earned income tax credit,” Review of Household Economics 8 (2) (2009), available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11150-009-9078-1.

48. U.S. Government Accountability Office, “GAO-21-245R: Child Care: Subsidy Eligibility and Receipt, and Wait Lists” (2021), available at https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-245r.

49. So Kubota, “Child care costs and stagnating female labor force participation in the US” (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Graduate School of Public Policy, 2018), available at https://ies.keio.ac.jp/upload/20180615appliedworkingpaper-1.pdf.

50. Jessica H. Brown and Chris M. Herbst, “Child Care and the Business Cycle.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 14048(Institute for the Study of Labor, 2021), available at http://ftp.iza.org/dp14048.pdf.

51. Rasheed Malik, “With Decreased Enrollment and Higher Operating Costs, Child Care Is Hit Hard Amid COVID-19” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2020), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/news/2020/11/10/492795/decreased-enrollment-higher-operating-costs-child-care-hit-hard-amid-covid-19/.

52. Umair Ali, Chris M. Herbst, and Christos A. Makridis, “The impact of COVID-19 on the U.S. child care market: Evidence from stay-at-home orders,” Economics of Education Review (82) (2021), available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272775721000170.

53. Caroline Krafft, Elizabeth Davis, and Kathryn Tout, “Child care subsidies and the stability and quality of child care arrangements,” Economics & Political Science Faculty Scholarship 40 (2017), available at https://sophia.stkate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1039&context=economics_fac; Anna D. Johnson, Rebecca M. Ryna, and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, “Child Care Subsidies: Do They Impact the Quality of Care Children Experience,” Child Development 83 (4) (2012), available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22694173/; Rebecca M. Ryan and others, “The Impact of Child Care Subsidy Use on Child Care Quality,” Early Child Research Quarterly 26 (3) (2001), available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3160790/.

54. Marsha Weinraub and others, “Subsidizing child care: How child care subsidies affect the child care used by low-income African Americans families,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 20 (2005), available at https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.565.2163&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

55. Ibid; Suzanne W. Helburn, John R. Morris, and Kathy Modigliani, “Family child care finances and their effect on quality and incentives,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (4) (2002), available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0885200602001886?via%3Dihub.

56. Gina Adams and Julia R. Henly, “Child Care Subsidies: Supporting Work and Child Development for Heathy Families,” Health Affairs (2020), available at https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20200327.116465/full/.

57. Office of Child Care, The Decreasing Number of Child Care Providers in the United States (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019), available at https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/news/the-decreasing-number-of-family-child-care-providers-in-the-united-states.

58. V. Joseph Hotz and Matthew Wiswall, “Child Care and Child Care Policy: Existing Policies, Their Effects, and Reforms,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 686 (1) (2019), available at https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0002716219884078.

59. For examples, see Blau, The Child Care Problem: An Economic Analysis; Maher, Frestedt, and Grace, “Differences in Child Care Quality in Rural and Non-Rural Areas”; Suzanne W. Helburn and Carollee Howes, “Child Care Costs and Quality,” Financing Child Care 6 (2) (1996), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/1602419?seq=1; Kimberly Boller and others, “Impacts of a child care quality rating and improvement system on child care quality,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 30b (1) (2015), available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0885200614001124.

60. Nicole Forry and others, “5 Ways to Improve the Quality of Early Care and Education” (Bethesda: Child Trends, 2013), available at https://www.childtrends.org/publications/5-ways-to-improve-the-quality-of-early-care-and-education; Martha Zaslow and others, “Toward the Identification of Features of Effective Professional Development for Early Childhood Educators” (Washington: U.S. Department of Education, 2010), available at https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/opepd/ppss/reports.html.

61. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2020, 39-9011 Childcare Workers (U.S. Department of Labor, 2021), available at https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes399011.htm.

62. Eric C. Twombly, Maria D. Montilla, and Carol J. De Vita, “State Initiatives to Increase Compensation for Child Care Workers” (Washington: Urban Institute, 2001), available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED452993.pdf.

63. Paul M. Romer, “Human Capital and Growth: Theory and Evidence,” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 32 (1990), available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/016722319090028J?via%3Dihub.

64. Bassam A. Albassam and Mariam Camarero, “A model for assessing the efficacy of government expenditure,” Cogent Economics & Finance 8 (1) (2020), available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23322039.2020.1823065.

65. For examples, see Executive Office of the President, The Economics of Early Childhood Investments; William T. Gormley, “Universal vs. Targeted Prekindergarten: Reflections for Policymakers.” In The Current State of Scientific Knowledge on Pre-Kindergarten Effects (Washington: The Brookings Institute, 2017); Jean Burr and Rob Grunewalk, Lessons Learned: A Review of Early Childhood Development Studies (Minneapolis: U.S. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, 2006); James J. Heckman and others, “The rate of return to the HighScope Perry Preschool Program,” Journal of Public Economics 94 (2010), available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0047272709001418; Center for High Impact Philanthropy, “Invest in a Strong Start for Children: High Return on Investment” (2015), available at https://www.impact.upenn.edu/toolkits/early-childhood-toolkit/; Jorge Louis Garcia and others, “The Life-Cycle Benefits of an Influential Early Childhood Program.” Working Paper 22993 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2016), available at https://ideas.repec.org/p/nbr/nberwo/22993.html.

66. Washington Center for Equitable Growth, “More than 200 economists to Congress: Seize ‘historic opportunity to make long-overdue public investments’ to boost economic growth” (2021), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/press/more-than-200-economists-to-congress-seize-historic-opportunity-to-make-long-overdue-public-investments-to-boost-economic-growth/.

67. Executive Office of the President, The Economics of Early Childhood Investments.

Related

Explore the Equitable Growth network of experts around the country and get answers to today's most pressing questions!