Factsheet: What does the research say about care infrastructure?

The United States is emerging from the greatest health, economic, and caregiving crises in a century. Many policymakers are looking for ways to jumpstart the economy and, recognizing the tie between infrastructure and economic growth, have turned their sights on investments in U.S. physical and care infrastructure.

In March 2021, President Joe Biden proposed the American Jobs Plan and American Families Plan, a multipart proposal that would boost federal spending on the nation’s care and physical infrastructure. (See textbox for details.) Investments of this kind could help the U.S. economy recover from the coronavirus recession and lead toward sustainable, broad-based economic growth in the future.

Care infrastructure includes the policies, resources, and services necessary to help U.S. families meet their caregiving needs. Specifically, care infrastructure describes high-quality, accessible, and affordable child care; paid family and medical leave; and home- and community-based services and support.

This factsheet presents some of the research and evidence on America’s care infrastructure as it relates to families’ caregiving needs, the care workforce, and U.S. economic growth.

The current state of U.S. care infrastructure

Caregiving is an important component of the economy. Research suggests that adequate care infrastructure can promote labor force participation, particularly among women; boost the human capital of care recipients; and support broad-based macroeconomic growth. Yet the evidence also suggests that U.S. care infrastructure is in need of greater investment, and current caregiving policies and resources may not be sufficient for the nation’s caregiving needs. For example:

- Child care costs more than in-state public college in 30 states, and more than half of all families live in so-called child care deserts, where the supply of licensed child care slots is insufficient for the number of children in that area. Despite these high prices, child care providers run on razor-thin profit margins, making them particularly vulnerable to changes in macroeconomic trends. Meanwhile, the median wage for a child care worker is only $25,460 per year.1

- The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates that today’s seniors will incur an average of $137,800 in future long-term services and supports costs, half of which will be financed out of pocket—an unaffordable amount for many. And while COVID-19 outbreaks were particularly devastating to nursing home residents, waitlists for home- and community-based services through Medicaid waivers remain long. In 2018, more than 800,000 Americans were on such a waitlist—approximately 45 percent of the total population already receiving these services.2

- For workers living in the 44 states that do not currently have an active paid family and medical leave system, finding time to focus on caregiving can be a challenge. Only 20 percent of private-sector workers access paid family leave through their employers, and 44 percent of U.S. workers do not even qualify for unpaid leave through the Family and Medical Leave Act, or FMLA.3

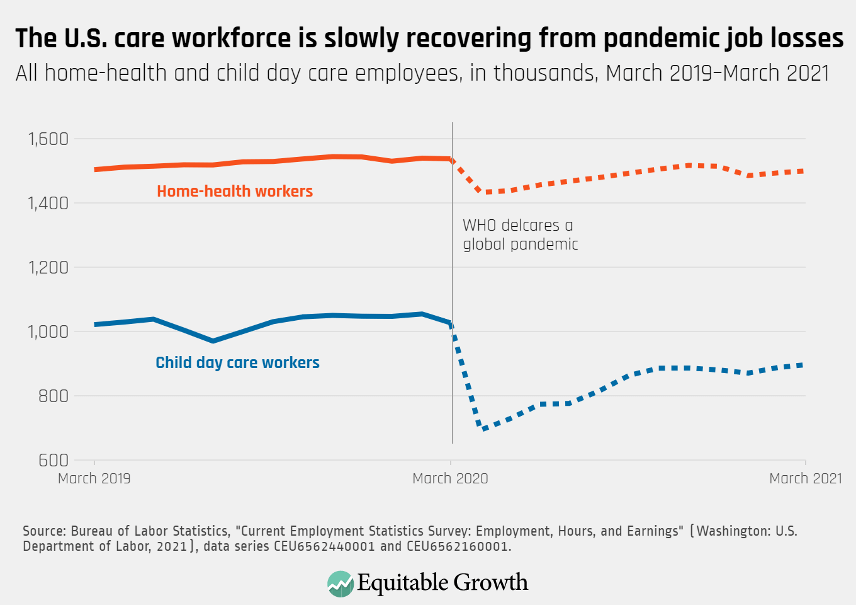

The COVID-19 pandemic and recession exposed preexisting flaws in the nation’s care infrastructure and further weakened an already-fragile system. Employment in the child care and home-health sectors remains depressed, suggesting the care economy could struggle to meet demand as the nation reopens, blunting the economic recovery. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Insufficient care infrastructure constrains the U.S. economy and worker well-being

- Paid caregivers earn less than workers in noncare jobs with comparable skills, employment characteristics, and demographics. Research demonstrates that professionals in the caregiving industry receive wages that are 20 percent lower than comparable professionals in other industries. Managers face a similar 14 percent penalty. These penalties translate to higher turnover, lower consumer spending, a smaller tax base, and reduced economic security than if care workers were valued the same as comparable noncare employees.4

- Turnover and disruptions in paid caregiving arrangements are burdensome for family caregivers. Recent research finds that the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted more than half of family caregiving arrangements. Family caregivers who face a caregiving disruption demonstrate increased anxiety and depression, and are 13.9 percentage points more likely to also experience permanent job separation or furloughs during the pandemic, compared with noncaregivers.5

- Informal caregiving may constrain the economy through lost productivity, wages, and benefits. In data collected by Gallup Inc., 24 percent of family caregivers report that caregiving keeps them from working more, and 30 percent report missing 6 or more days of work in the prior year due to caregiving duties. These productivity losses are estimated to cost the U.S. economy more than $25 billion per year. A 2011 study by the Metlife Mature Market Institute estimates that aggregate cost to the U.S. economy from lost wages, pensions, and Social Security benefits for these family caregivers is nearly $3 trillion.6

- Caregiving concerns may have driven millions of women out of the workforce in the COVID-19 pandemic. Research shows that caregiving concerns contributed to more than 2.3 million women exiting the labor force between February 2020 and February 2021. By March 2021, the labor force participation rate for women was 56.1 percent, the lowest rate since May 1988. The gap between men’s and women’s labor force participation widened in communities where school closures exacerbated caregiving needs. Time out of the workforce has long-term implications: Research shows that 13 percent of the gender pay gap can be ascribed to time spent outside of the labor force caring for others.7

Investments in care infrastructure boost economic growth, labor force participation, and worker well-being

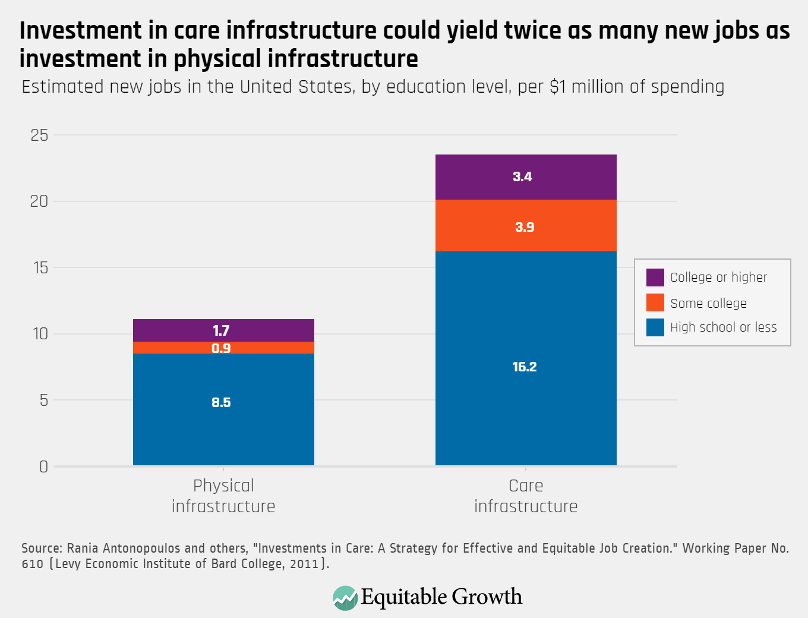

- Investments in care infrastructure have the potential to create twice as many new jobs as investments in physical infrastructure alone. In the wake of the Great Recession a decade ago, researchers estimate that investment in early childhood development and home-based healthcare could have created 23.5 new jobs per $1 million spent, compared to 11.1 jobs from physical infrastructure investments. Approximately 85 percent of new jobs from both care and physical infrastructure investments would reach workers with lower levels of educational attainment.8 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

- Spending in the care economy would strengthen women’s employment and reduce the gender employment gap. An analysis of care spending in seven OECD countries, including the United States, estimates that an investment in the care economy equal to 2 percent of Gross Domestic Product would raise the employment rate for U.S. women and men by 8.2 percentage points and 4 percentage points, respectively. This would reduce the gender employment divide by 4.2 percentage points.9

- Accessible and affordable child care can facilitate labor force participation and support economic growth. Research shows that parents’ labor force participation increases when child care is more affordable and accessible. In one study, a 100-slot increase in the supply of child care in a community is estimated to raise women’s labor force participation for the entire community by 0.3 percentage points. Conversely, every $100 increase in the price of child care is associated with a 3.7 percentage point decrease in that neighborhood’s labor force participation rate among women.10

- Meanwhile, high-quality early care and education can lead to long-term improvements in a child’s human capital. Children in high-quality programs demonstrate better education, economic, health, and social outcomes and fewer negative outcomes—such as involvement in the criminal justice system. These high-quality programs can help pay for themselves, generating up to a 13 percent return on investment per-child, per-year.11

- Much of the research evidence shows paid leave has a range of positive outcomes for caregivers and care recipients. A growing body of research suggests that paid parental leave can improve a range of childhood outcomes, including infant mortality, low birth weight, preterm birth, breastfeeding rates, and pediatric head trauma, as well as later-in-life outcomes, including lower rates of attention deficit disorder and obesity. Additionally, evidence from California suggests paid caregiving leave can reduce nursing home occupancy among the elderly patients, likely due to enhanced access to family caregivers. And while research on paid medical leave is still comparatively scant, research on related programs indicates such leave can lead to positive health and economic outcomes, as employees have more time and resources to focus on their own well-being.12

- Paid leave may also improve labor market outcomes for caregivers. The bulk of the research finds positive associations between paid leave and women’s labor force participation, though the relationship remains nuanced. Evidence from California indicates that under the state’s paid leave law, new mothers are 18 percentage points more likely to be working the year after the birth of their child, compared to mothers without paid leave access. Recent research corroborates these findings, indicating an approximately 20 percent increase in the probability of labor force participation during the year of a child’s birth. This increase remains significant up to 5 years later.13

- Patients transitioning from institutions to lower-cost home- and community-based services experience better quality of life and fewer unmet needs. Research shows that patients who transition from institutional care to home-based care express greater life satisfaction (66 percent compared to 83 percent) and fewer unmet care needs (18.3 percent compared to 7.6 percent), compared to their time in institutions. In the same analysis, patients transitioning from nursing home facilities demonstrate 18 percent to 24 percent declines in healthcare spending in their first year in home- and community-based care.14

- Home-based care may be particularly valuable for patients without access to family caregivers. Research demonstrates that higher levels of state home-health spending is associated with a significant reduction in the risk of nursing home admission among childless patients.15

Conclusion

Inefficiencies in the nation’s current care infrastructure—paid family and medical leave, child care, and home-based services and supports—constrain economic growth, and leave families and businesses vulnerable to unexpected health and caregiving shocks. Caregiving work is undervalued, and many U.S. workers across the economy face a financial penalty for engaging in care work, which can lead to high turnover and caregiving instability. When care workers are not available or not affordable, family members take on new caregiving responsibilities, exacerbating work-life challenges. If family caregivers cannot resolve these challenges, then many are forced out of the workforce—costing the economy trillions of dollars in lost productivity and compensation.

Alternatively, research suggests that investments in care infrastructure could create significantly more new jobs than investments in physical infrastructure alone, boosting GDP growth and reducing the gender employment divide. Research on the individual components of the care economy likewise support further investment.

Accessible, affordable, and high-quality child care is associated with employment gains for parents in the short term and human capital improvements for children in the long term. Likewise, a preponderance of the evidence on paid leave indicates positive labor market outcomes for caregivers and health and well-being outcomes for care recipients. Finally, patients who transition out of institution-based long-term care report better quality of life, fewer unmet care needs, and lower healthcare costs.

Altogether, the bulk of the research and evidence suggests investments in care infrastructure are a promising tool to boost U.S. economic growth, productivity, and well-being. Policymakers looking to jumpstart the U.S. economic recovery from the coronavirus recession, ensure broad-based future economic growth, and provide much-needed support to U.S. workers and their families must prioritize investment in both physical and care infrastructure.

End Notes

1. Child Care Aware of America, “The US and the High Price of Child Care” (2019); Rasheed Malik and others, “The Coronavirus Will Make Child Care Deserts Worse and Exacerbate Inequality” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2020); Jessica H. Brown and Chris M. Herbst, “Child Care Over the Business Cycle,” IZA Discussion Paper No. 14048 (IZA Institute of Labor Economics, 2021); U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Child Care Works.” In Occupational Outlook Handbook (Washington: Department of Labor, 2021).

2. Melissa Favreault and Judith Dey, “Long-Term Care Services and Supports For Older Americans: Risks and Financing, 2020” (Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2021); Kaiser Family Foundation, “Waiting List Enrollment for Medicaid Section 1915(c) Home and Community-Based Services Waivers” (2018).

3. National Partnership for Women and Families, “State Paid Family and Medical Leave Insurance Laws: January 2021” (2021); U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “National Compensation Survey, Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2020” (Washington: Department of Labor, 2020); Scott Brown and others, “Employee and Worksite Perspectives of the Family and Medical Leave Act: Results from the 2018 Surveys” (Washington: U.S. Department of Labor, 2020).

4. Nancy Folbre and Kristin Smith, “The wages of care: Bargaining power, earnings and inequality.” Working Paper (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2017); Robert Holly, “Home Care Industry Turnover Reaches All-Time High of 82%,” Home Health Care News, 2019.

5. Yulya Truskinovsky, Jessica Finlay, and Lindsay Kobayashi, “Caregiving in a Pandemic: COVID-19 and the Well-being of Family Caregivers 55+ in the U.S.” Working Paper (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2021).

6. Dan Witters, “Caregiving Costs U.S. Economy $25.2 Billion in Lost Productivity” (Washington: Gallup Inc., 2011); Metlife Mature Market Institute, “The MetLife Study of Caregiving Costs to Working Caregivers” (New York: Metlife Services and Solutions LLC, 2011).

7. Titan Alon and others, “From Mancession to Shecession: Women’s Employment in Regular and Pandemic Recession.” Working Paper 28632(National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021); The National Women’s Law Center, “A Year of Strength & Loss: The Pandemic, The Economy, and The Value of Women’s Work” (2021); U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Labor Force Participation Rate – Women [LNS11300002]” (n.d.), retrieved from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; Caitlyn Collins and others, “The Gendered consequences of a Weak Infrastructure of Care: School Reopening Plans and Parents’ Employment During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Gender and Society (2021); Jérôme Adda, Christian Dustmann, and Katrien Stevens, “The Career Costs of Children,” Journal of Political Economy 125(2) (2017): 293–337.

8. Rania Antonopoulos and others, “Investing in Care: A Strategy for Effective and Equitable Job Creation.” Working Paper No. 60 (Levy Economic Institute of Bard College, 2011).

9. Jérôme De Henau and others, “Investing in the Care Economy: A gendered analysis of employment stimulus in seven OECD countries” (Brussels: International Trade Union Confederation, 2016).

10. Taryn W. Morrissey, “Child care and parent labor force participation: a review of the research literature,” Review of Economics of Households 15 (2016): 1–24; Chris M. Herbst and Burt S. Burnow, “Close to Home: A Simultaneous Equations Model of the Relationship Between Child Care Accessibility and Female Labor Force Participation,” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 29 (2008): 128–151.

11. James Heckman, “Invest in Early Childhood Development: Reduce Deficits, Strengthen the Economy” (The Heckman Equation,2013).

12. Elisabeth Jacobs, “Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States: A Research Agenda” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2018); Rui Huang and Muzhe Yang, “Paid maternity leave and breastfeeding practice before and after California’s implementation of the nation’s first paid family leave program,” Economic & Human Biology 16 (2015): 45–59; Joanne Klevens and others, “Paid family leave’s effect on hospital admissions for pediatric abusive head trauma” Injury Prevention 22(6) (2016): 442–445; Shirlee Lichtman-Sadot and Neryvia Pillay Bell, “Child Health in Elementary School Following California’s Paid Family Leave Program,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 36 (4) (2017): 790–827; Kanika Arora and Douglas A. Wolf, “Does Paid Leave Reduce Nursing Home Use? The California Experience,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 37 (1) (2018): 38–62; Jack Smalligan and Chantel Boyens, “Paid Medical Leave Research” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020).

13. Alix Gould-Werth, “New paid leave research demonstrates challenge of balancing work and caregiving” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2019); Charles L. Baum II and Christopher J. Ruhm, “The Effects of Paid Family Leave in California on Labor Market Outcomes,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 35 (2) (2016): 333–356; Kelly Jones and Britni Wilcher, “Reducing maternal labor market detachment: A role for paid family leave.” Working Paper (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020).

14. Carol V. Irvin and others, “Money Follows the Person 2015 Annual Evaluation Report” (Baltimore, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2017).

15. Naoko Muramatsu and others, “Risk of Nursing Home Admission Among Older Americans: Does States’ Spending on Home- and Community-Based Services Matter?” The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 62 (4) (2007): S169–S178.