Overview

Caregiving needs in the United States reach across the life cycle. Every day, 10,800 babies are born, 4,754 new cases of cancer are diagnosed, and 1,329 people develop Alzheimer’s disease. 1 Yet millions of working Americans lack access to paid leave, forcing impossible choices between their caregiving responsibilities at home and their economic responsibilities at work. Workers who need time off to care for a new baby, a sick child, an aging family member, or their own health needs may do so at the expense of their financial well-being—or their jobs.

While the federal Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 provides the right to 12 weeks of job-protected unpaid leave, the law’s dated eligibility requirements mean that about 40 percent of workers are excluded from this coverage. The workers that would benefit the most from leave account for most of these low coverage rates, with about half of all working parents and 43 percent of women of childbearing age ineligible for job-protected leave under FMLA. 2

Many eligible workers are unable to take unpaid leave due to an inability to weather the earnings loss during the leave period. A recent study by the Pew Research Center found that one in six U.S. workers employed in the past 2 years needed to take a medical or caregiving leave during this period, and nearly three out of four (72 percent) of these workers cited the consequent earnings losses as their main reason for foregoing leave. 3 Black and Hispanic workers, workers without a college degree, and workers in households with annual incomes of less than $30,000 were all even more likely to forego needed caregiving leave. Just more than half (54 percent) of those who didn’t take leave when they needed to say they didn’t take the time off from work because they feared losing their job.

A small minority of private-industry workers (13 percent) are covered by employer-based paid leave programs. 4 The share of workers with access to paid leave through an employer varies sharply by earnings. Among low-wage workers in the bottom quarter of the earnings distribution, just 6 percent have access to employer-based coverage for paid leave to care for a new child or an ailing family member. 5 Employer-based coverage providing paid leave for one’s own short-term disability is somewhat more widespread, covering 39 percent of the civilian workforce. But just 19 percent of workers in the bottom earnings quartile had access to short-term disability. 6

Moreover, this private short-term disability leave is available for medical leave only and cannot be used to help cover a temporary leave to attend to family caregiving responsibilities. For most workers, if access to paid time off is available for leave, it is via either sick or vacation days rather than dedicated paid family medical leave. Yet those at the bottom of the earnings ladder have limited access even to these types of leave, with just less than a third of the bottom 10 percent of private-sector wage earners having any paid sick days and just 42 percent having any paid vacation days. 7

In the absence of federal policy, a growing number of states are taking action and implementing their own paid family and medical leave policies. Four states have implemented paid leave programs: California (2004), New Jersey (2009), Rhode Island (2014), and New York (2018). Two more have passed paid leave legislation and are working to implement the policies in the coming years: Washington (passed in 2017, implementation begins in 2019) and Massachusetts (passed in 2018, implementation begins in 2019), as well as the District of Columbia (passed in 2017, implementation effective 2020). 8 Twenty-five other state legislatures have active paid leave legislation under consideration. 9

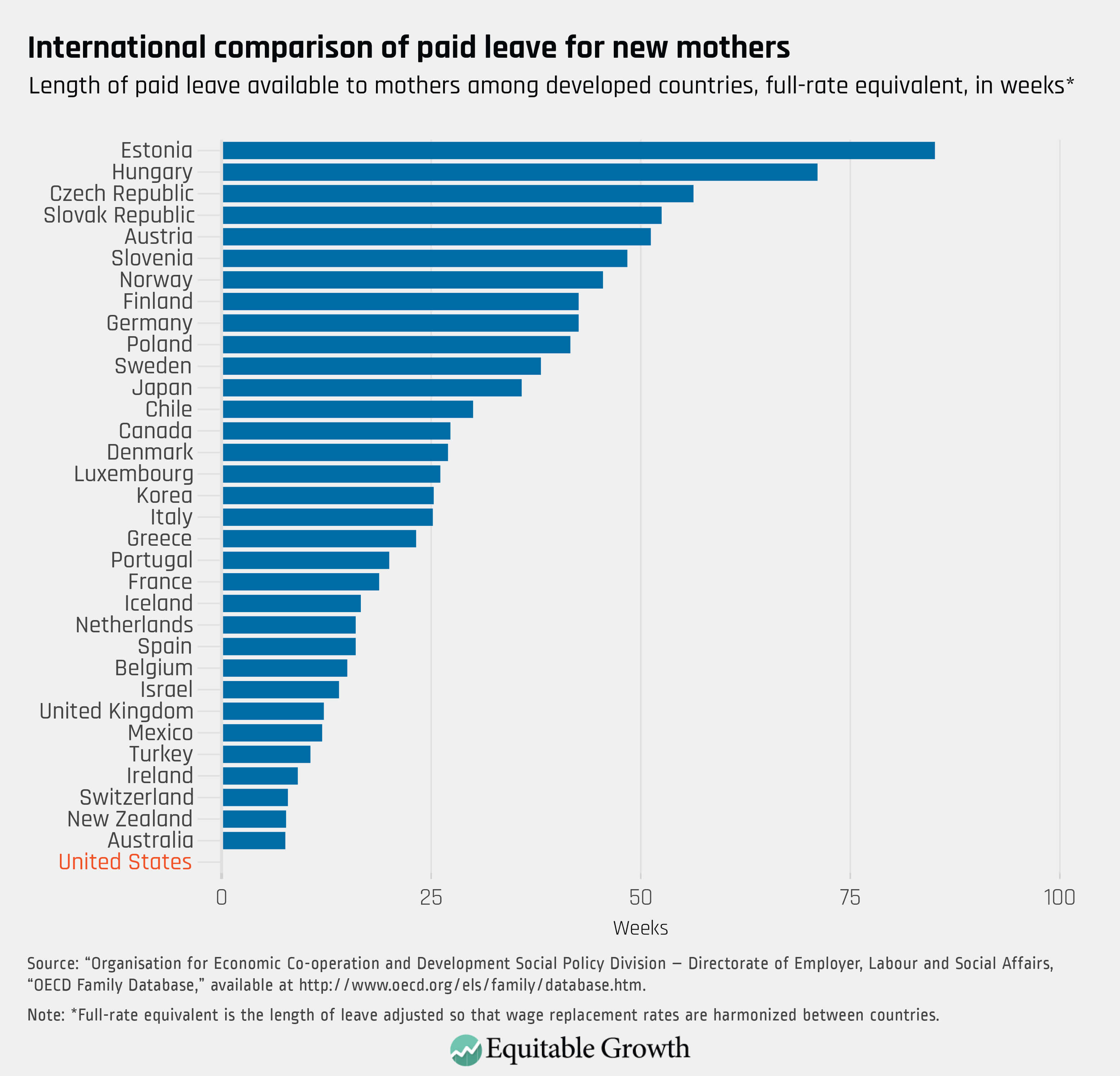

The graduated roll-out of family and medical leave across a growing number of states provides an opportunity for growing the knowledge base around paid family and medical leave across a wide variety of topics. Early-adopter states can serve as policy laboratories not only for other state legislators but also for federal policymakers interested in bringing paid family medical leave to scale at a national level. This research opportunity is paramount for academics and scholars alike. The absence of paid leave policies at the federal level in the United States means that, until very recently, the scholarship on paid family and medical leave policies that informed debates around policy design and implementation relied on European data. Differences between the U.S. and European political economies, cultural differences, as well as the fact that many European countries’ paid leave policies are substantially more generous than the benchmark 12 weeks of FMLA leave create challenges to drawing meaningful policy conclusions for the United States from the scholarly evidence. 10

All of this is changing, as the action in the early-adopter states alongside more than two decades of data on federal unpaid leave has altered the empirical landscape. A growing body of research is helping expand the evidence illuminating how paid family and medical leave impacts workers, their families, businesses, and the economy as a whole. At the same time, many questions remain about the short- and long-term consequences of paid leave and about the effects of the absence of paid leave on a variety of economic variables. The experimentation at the state level, combined with early research on the consequences of federal unpaid leave, make the United States newly fertile territory for scholarship, with key lessons for policymakers looking to address the interwoven issues of family economic security and macroeconomic growth.

This report provides a survey of what we know—and what we need to know—about paid family and medical leave in the United States. In addition to offering an overview of the existing academic literature, the pages that follow reflect many hours of informational interviews with key stakeholders and researchers in the field, as well as a day-long meeting hosted by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth that brought together a diverse group of experts from the academic and policy communities in order to elevate key research questions for the field.

Three central lines of inquiry form a framework for a research agenda going forward, with this report structured on that scaffolding. Specifically, what do we know and what do we need to know about how paid leave affects:

- Individuals and their families, including labor market outcomes for leave-takers and health effects for care recipients and leave-takers

- Businesses, including turnover costs and productivity

- The economy as a whole, including the macro- and microeconomic consequences

Throughout, whenever possible, the research is distilled for each type of leave—parental leave (to care for a new baby), medical leave (to care for one’s own illness), and caregiving leave (to care for an ill family member), given that variations in care responsibilities may have different ramifications across a host of outcomes. And, perhaps most critically, each section concludes with a set of key questions that together form a detailed research agenda to inform policy going forward.

As policymakers across the ideological spectrum grapple with identifying pragmatic, empirically backed solutions to easing the work-life conflict between family caregiving and labor market responsibilities, the growing body of evidence from the states offers a great deal of promise for guiding decision-making. It is worth noting up front that because research questions remain, it does not mean that the current state of the evidence implies that more research is necessary before action. The successful implementation and performance of comprehensive paid leave policies at the state level should be taken as a sign that paid leave policies are, in fact, doable—and a growing body of evidence suggests promising short- to medium-term outcomes for families, business, and the economy.

At the same time, the host of remaining unanswered questions provide a useful roadmap for researchers looking to inform the design of effective, efficient solutions that simultaneously bolster family economic security, minimally disrupt business operations, and foster broadly shared economic prosperity. The window of opportunity for building a research agenda that improves policy efficacy through timely, well-designed research is open, and now is the time to seize it.

What do we know about the effects of paid family and medical leave on individual-level health and employment outcomes?

The vast majority of the existing scholarship on family and medical leave policy in the United States focuses on individual outcomes, including labor market outcomes for leave-takers, health outcomes for care recipients, and, to a lesser degree, health and labor market outcomes for caregivers. In the following sections, we provide an overview of the knowledge base on each of these topics, looking at the experience of the states and, where relevant, national-level data, and draw out a set of research questions that remain in search of more evidence.

Labor market outcomes

Parental leave

Much of the earliest work looking specifically at the United States focuses on the effects of unpaid parental leave in the aftermath of the passage of the Family and Medical Leave Act in 1993. Despite the gender neutrality of the legislation, FMLA led to increases in leave-taking for mothers but has had little to no significant impact on fathers’ likelihood of paternity leave. 11 The 25-year-old law has extended the duration of paternity leave for those who take it—increasing the duration of leave by 4 percentage points—yet because fathers’ leaves around childbirth are typically limited to a day or two within the first few days of a child’s life, the absolute gains are quite small. 12 The increase in women’s leave-taking in response to job-protected, unpaid leave is driven almost entirely by women with a college degree, who tend to be higher earners. 13 These findings suggest limits to the labor market consequences of unpaid leave policies and the potential importance of paid leave policies to induce leave-taking among both fathers and economically vulnerable groups.

In the absence of public paid leave policies such as those widely available throughout the developed-economy member nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, researchers interested specifically in the U.S. case have turned to employer-based paid leave in order to better understand how paid parental leave impacts labor force outcomes in the American context. For instance, studies of employer-based policies in the United States in the 1980s and 1990s suggest that mothers with access to paid maternity leave work later into their pregnancies and are more likely to spend the month following birth caring for their child, though they return to the labor market at a higher rate than their peers without access to paid leave. 14 But the limited availability of employer-based paid leave in the United States, coupled with the difficulty of accessing private-sector data, means that the research on the results of paid leave via private-sector policies is of limited utility for U.S. policymakers seeking to better understand how to expand access to policies that facilitate a better balance between work and care responsibilities.

The enactment of California’s paid family and medical leave program in 2004—and the subsequent implementation of similar programs in New Jersey, Rhode Island, and New York over the past decade—provide new opportunities for the study of how paid parental leave may affect labor market outcomes for parents in both the immediate aftermath of a birth, as well as longer-term consequences over time. New Jersey and California’s policies are associated with an increase in overall women’s labor force attachment around the time of a birth. 15 The existing literature on the importance of sustained labor force participation rates over the course of a lifetime suggest that an increase in women’s labor force attachment has the potential for long-term benefits on women’s employment outcomes. 16

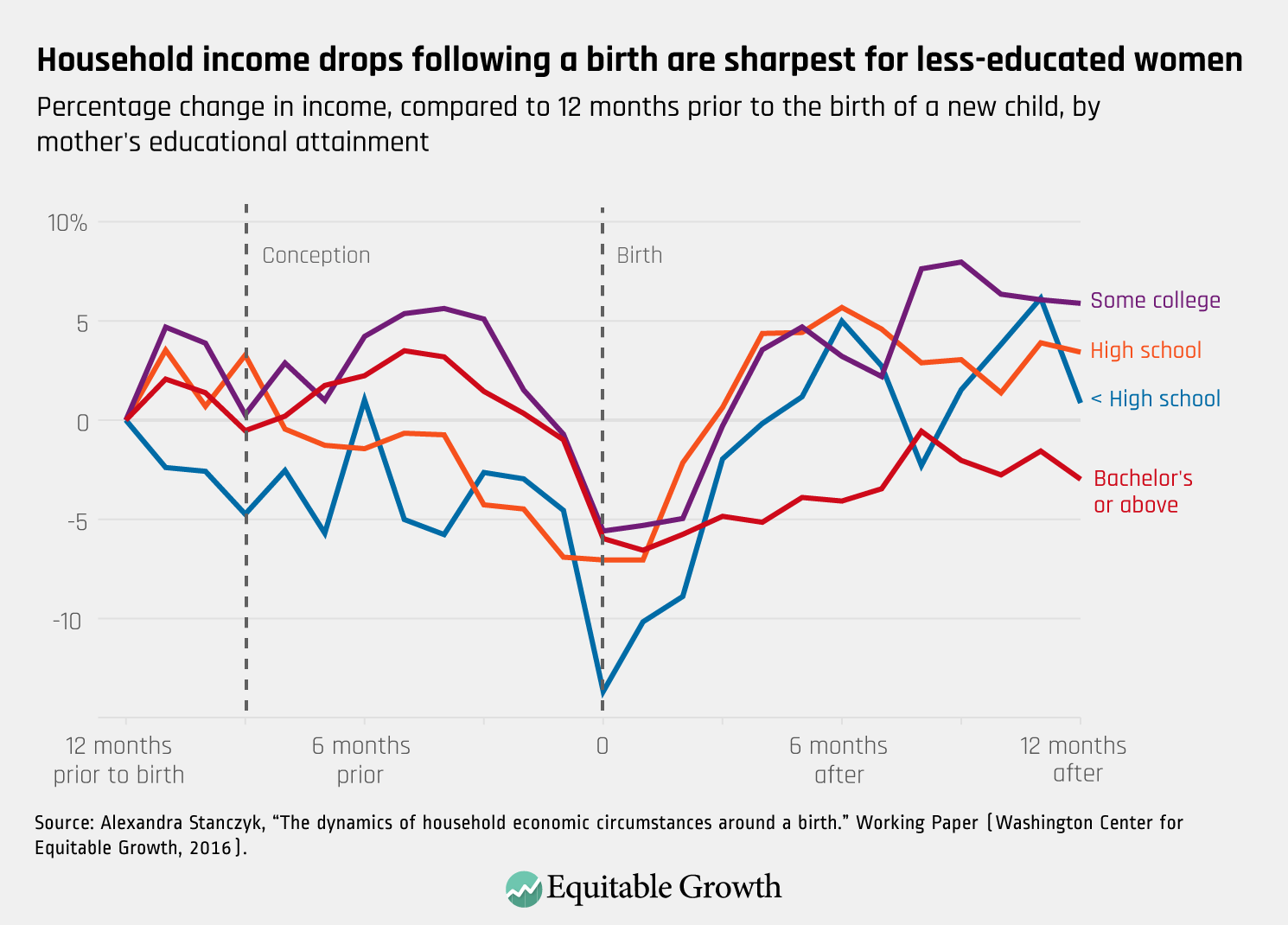

What’s more, much of the benefits of paid parental leave policies in those states accrued to workers at the bottom of the economic distribution. Research on California and New Jersey indicates that the increase in labor force attachment in the months following a birth is driven almost entirely by less-educated women, who are less likely to have access to or to take leave in the absence of the state policy. 17 More than 20 percent of workers in low-quality jobs in California report that taking parental leave improved their ability to find childcare, which may help explain their increase in labor force attachment relative to peers without access to paid leave. 18 Given that low-wage, less-educated workers are least likely to be covered by federal protections requiring access to unpaid leave, as well as least likely to be able to afford an unpaid leave in the presence of job-protected FMLA leave rights, it is not surprising that broadly accessible paid leave policies in the states are proving to be the most beneficial for these groups of workers.

Research on the state programs suggests that the labor market outcomes for paid parental leave endure beyond the first year of a child’s life. In California, new mothers were estimated to be 18 percentage points more likely to be working a year after the birth, with both work hours and weeks worked predicted to rise by significant amounts in the following year. 19 During the second year of their children’s lives, mothers’ work hours increased by 18 percent and their weeks at work increased by 11 percent, relative to their peers prior to the implementation of the state’s paid parental leave policy. 20 These increased work hours and weeks at work translate into higher earnings for mothers covered by paid parental leave policies. Yet the enduring effects of paid leave appear to vary by earnings level at the time of the claim for paid leave. High-earning mothers and fathers are more likely than lower earners to be continuously employed for 5 to 6 years following a claim. 21 Higher weekly benefit amounts boost labor force participation for mothers 1 to 2 years following leave, though due to the research design, this finding is limited to high-wage women whose earnings are near the benefit threshold. 22

California’s experience also suggests that paid parental leave increases the share of fathers taking leave to bond with a new child. In two-earner households, the policy increased men’s probability of taking father-only leave (when a father takes leave to provide care for a new baby on his own) by 50 percent and boosted the likelihood of joint leave (when both the father and his partner take leave together to care for a new baby) by 28 percent. Notably, California’s program increased father-only leave for fathers of sons only; fathers of daughters were no more likely to take their own leave than they were prior to the existence of the public leave program. This gender difference is also reflected in the probability that both parents are on leave at the same time. The increase in father-only leave-taking is entirely driven by leaves taken after first births and is concentrated among fathers who work in occupations with a high share of female workers. 23 In addition to their high probability of taking up paid postpregnancy recovery leave through California’s Temporary Disability Insurance program (the medical leave component of paid family leave), women are far more likely than men to take the full six weeks of the bonding leave available through state Paid Family Leave program. Only 4 in 10 fathers take advantage of the six weeks of bonding leave available to them; most of the remainder take between two to five weeks of bonding leave. 24

Caregiving and medical leave

The vast majority of the research in both the United States and abroad focuses on the impact of parental leave on labor market outcomes, which means the current literature provides less evidence about the labor market effects of caregiving leave (time off work to care for a seriously ill family member or loved one) and medical leave (time off work to care for one’s own serious illness). State administrative data on their paid family and medical leave programs suggest that medical leave is far more common than either parental or caregiving leave. Over the first 10 years of California’s program, workers registered more than 9 million medical leave claims, compared to nearly 1.6 million parental leave claims and just 175,198 caregiving claims. 29 In New Jersey, only one in five family leave claims are for caregiving, and the ratio is even smaller when considering the large number of medical claims under New Jersey’s Temporary Disability Insurance program. 30

Preliminary evidence from California suggests that paid caregiving leave increased the short-run labor force participation of caregivers by 8 percent in the first 2 years following implementation and by 14 percent in the first 7 years of the program. 31 But women made up the entirety of the increase in labor force participation, highlighting that even in the presence of paid caregiving leave, women continue to take on the majority of caregiving responsibilities across a family’s generational life cycle. In the first 2 years following implementation, the majority of the increase in caregivers’ labor force participation was among those from high-income households. In the longer term, however, labor force participation for low-income caregivers overtook those from higher-income households, indicating the particular importance of paid caregiving leave for promoting labor force attachment among lower-income workers.

The relatively low rate of claims for caregiving leave raises a host of questions, given the prevalence of family caregiving and the well-documented economic strains that caregiving responsibilities can place on the caregivers. More than half of all adults ages 52 and older who have a living parent or parent-in-law with a recently deceased spouse have parental caregiving responsibilities, and 18 percent of adults in this age group with a surviving or recently deceased spouse have or have had spousal caregiving responsibilities. 32 More than half of today’s caregivers are employed, even in the absence of widespread availability to paid leave policies, and research shows that caregiving increases the likelihood of poverty and reliance on public assistance, as well as finding positive associations between caregiving during prime working-age years and lower incomes later in life. 33 Other studies find that caregiving is associated with both lower labor force participation and lower net worth for family caregivers as compared to noncaregivers, with particularly detrimental consequences on spousal caregivers. 34 Recent surveys indicate that among leave-takers who received partial or no pay during their time off, 36.5 percent fell behind on bills, 30.2 percent borrowed money, and 14.8 percent enrolled in public assistance benefit programs. 35

The research on the labor market outcomes of medical leave is even thinner than that on caregiving leave. Yet the vast majority of claims made to the existing state paid family and medical leave programs are for medical leaves. In other words, the most common type of paid leave claim is for time away from work to care for one’s own health. The paucity of research in this area may be because medical leave covers the need to take time away from work for a host of reasons such as intermittent leave for recurring cancer treatments or a concentrated period of leave for a hip replacement surgery. Pregnancy-related leave also is covered under medical leave component of these programs, including both leave prior to a birth and the postbirth recovery period. The wide variety of illnesses requiring leave may make it difficult to effectively isolate the role of paid leave in shaping labor market outcomes. For this reason, existing studies focus on a subset of workers or on one particular ailment. 36

New research is pushing forward on uncovering the labor market effects of temporary disability insurance for medical leave. One recent study using administrative data from Rhode Island’s medical leave program finds that recipients of temporary disability leave who received vocational rehabilitation services were more likely to return to work and earn higher wages upon their return to work than those who did not receive those services. 37 Yet far more research is needed in order to have a robust evidence base on how medical leave impacts labor market outcomes.

Health outcomes

Parental leave

Paid parental leave’s impact on children’s health outcomes is a central and powerful argument for expanding access. International evidence looking across low- and high-income countries suggests that paid maternity leave delivers powerful benefits for infant mortality, a key indicator of population health. 38 The comparative studies suggest that the introduction of parental leave policies plays a critical role in lowering rates of infant mortality and low birth weight, and that longer leave policies correlate with better infant health and lower child mortality rates. 39 Yet context matters, as the countries studied have different health care, childcare, and labor policies that may interact with paid parental leave and make it difficult to extrapolate to the impacts of a potential U.S. policy.

Moreover, using cross-national comparisons creates methodological complications that can make it difficult to isolate effects meaningfully. Cross-national comparisons typically include both the introduction and extension of paid parental leave policies, but problems with endogeneity—the possibility that an unknown factor is driving both the extension of parental leave, as well as trends in the outcome of interest—make it difficult to interpret the findings in a meaningful way. Single-country studies typically find little impact of paid parental leave on health, but those limited consequences are probably because the variation available for study in single-country studies comes from extensions of existing policy rather than the introduction of new policy. Indeed, the main health effects of parental leave policy typically come from the introduction of new policy rather than extension of existing policy. 40 This is why new research from the U.S. states that have introduced paid family and medical leave policies is so critical. From a theoretical standpoint, there are good reasons to believe that paid parental leave may impact not only infant health but also children’s health outcomes over the long term.

A small set of academic literature in the United States identifies promising evidence of positive outcomes for infant health associated with parental leave. Following the implementation of the Family and Medical Leave Act, mothers’ ability to take unpaid leave to care for a new baby resulted in a 10 percent reduction in infant mortality. 41 The reduction in infant mortality, however, was concentrated among mothers with more education; less-educated and single mothers saw no change in infant mortality rates as a result of FMLA. Given how poorly federal unpaid leave policies do in providing access to job-protected leave for low earners and other vulnerable populations, these findings are not especially surprising. Moreover, given that the high rates of infant mortality in the United States are driven entirely by the poor birth outcomes of low-income mothers, the findings also point to the potential for broader access to paid leave as a mechanism for substantially lowering infant mortality in the United States. 42

New research from the states also shows glimmers of promise for paid parental leave as a mechanism for improving infant health. The introduction of paid parental leave in California resulted in a significant decrease in hospital admissions for pediatric head trauma for infants and young toddlers, a leading cause of child abuse maltreatment. 43 The researchers hypothesize that paid parental leave may have reduced parental stress, which, in turn, mitigated child abuse. In addition, paid maternity leave in California increased the rate and duration of breastfeeding. 44 A long literature indicates myriad short- and long-term health benefits of breastfeeding for children, suggesting that health impacts of paid leave may also flow through this channel. 45

While the impact of paid parental leave on infant health is an obvious starting place, paid time off early in a child’s infant life may have significant ripple effects across the life cycle such that the health effects of paid leave may last significantly past early childhood. One study on the long-term benefits of paid parental leave in California finds improvements in health outcomes among kindergarteners, including lower rates of diagnoses of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, lower rates of obesity, lower rates of ear infections, and fewer hearing problems. 46 The benefits of paid parental leave were most apparent among children with lower socioeconomic status. And all of these health outcomes are negatively correlated with the infant health factors that other research suggests paid parental leave promotes, including breastfeeding, timely infant medical check-ups, re-educated prenatal stress, and reduced nonparental care during infancy.

While most of the research on child health outcomes focuses on mothers as the primary channel mediating health outcomes, parental leave may also impact child health outcomes through fathers’ interactions. Research establishes that the quality and quantity of interactions that a father has with his children in early life can contribute to their cognitive development over a lifetime, independent of mothers’ levels of sensitivity. 47 Studies of California’s paid leave program suggest that gender-neutral paid parental leave that allows both fathers and mothers to take bonding leave with a new child significantly boost men’s take-up rates, compared to unpaid leave options. One rigorous study found that California Paid Family Leave policy raised the likelihood that a working father would take leave in the first year of his child’s life by 0.9 percentage points—a large increase, given the very low levels of leave taken by fathers. 48 In short, while mothers are still more likely to take leave, fathers are far more likely to take parental leave if that leave is paid.

Paid parental leave also may result in significant health benefits for parents. The public paid maternity leave programs in the United States with the longest timeframe available for study are the four state Temporary Disability Insurance programs, which provide access to maternity leave benefits under the legal requirement that pregnancy be recognized as a medical condition in accordance with the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978. 49

A small vein of research in the United States connects paid maternity leave with maternal mental health outcomes. Longer maternity leaves are associated with lower rates of depression and higher overall levels of maternal health. Paternity leave also may be critical to maternal health, as mothers with spouses who did not take parental leave have higher rates of maternal depression than their peers with spouses who took leave, controlling for a host of other factors. 50 Short-term maternal health in the months following a birth may have significant long-term mental health consequences through a variety of mechanisms. For instance, temporarily removing the competing demands of work and family may eliminate “role overload” for new mothers, which can give rise to additional stressors that trigger a cascade of stress proliferation. Leave policies also may improve mother-child relationships and reduce later risks of disorders in children, thereby improving the maternal well-being of mothers as their children grow up. Finally, leave policies may impact mental health vis-à-vis the effects of leave on employment and earnings outcomes; higher levels of economic security may have positive externalities for late-life maternal mental health. 51

The evidence in Europe of the benefits of paid leave and maternal mental health points is overwhelming. One study of European mothers finds that depression among women over the age of 50 was strongly negative correlated with the length of maternity leave for their first child. In other words, new mothers who were able to take lengthy parental leaves were far less likely to be depressed in their older years. 52 Of course, like other studies based on European data, these findings should be treated with caution when applied to the U.S. case, but they provide promising evidence for research lines to be mined.

A second major health impact of paid parental leave may be the link between breastfeeding and maternal health. Studies in California find that the introduction of paid parental leave increased exclusive breastfeeding rates by 3 to 5 percentage points and increased rates of any breastfeeding by 10 points to 20 points at several key timepoints of importance for an infant’s nutrition and health. 53 Research linking maternity leave to increased rates of breastfeeding note the evidence of the importance of breastfeeding for maternal health, not just infant health, including both long- and short-term results. 54 In the short term, breastfeeding is associated with a reduced risk of postpartum depression among new mothers, as well as a decreased risk of re-hospitalization following a birth. 55 In the long term, breastfeeding for 12 or more months is associated with a 32 percent reduction in Type 2 diabetes, a 26 percent reduction in the risk of breast cancer, and a 37 percent reduction in the risk of ovarian cancer. 56

Medical and caregiving leave

The scholarship on health-related outcomes stemming from access to paid medical and caregiving leave is less well-developed than that of parental leave. Because of the diversity of diagnoses and family circumstances that surround the need to take leave—either for one’s own serious illness or to care for a family member with a serious illness—effectively designing research to investigate the nuances of such types of leave is substantially more difficult than research projects designed to understand the (relatively) more standardized caregiving needs surrounding the arrival of a new child into a family.

The majority of unpaid leave claims under the Family and Medical Leave Act are for medical leave, and in both California and New Jersey, about one in two paid leave claims are filed for personal medical reasons not related to childbirth. In both states, claims filed for personal medical reasons are for substantially longer durations than claims filed for family caretaking. The most commonly given reasons for nonchildbirth related medical leave claims in New Jersey include “disabilities related to bones and organs of movement, and disabilities resulting from accidents, poisoning, and violence,” according to the New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. 57 In contrast, the number of claims for caregiving leave is relatively small, which creates challenges for researchers due to the resulting small sample size available for study.

While the number of claims is relatively small, the data indicates a high degree of unmet needs for both paid medical leave and paid caregiving leave. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ National Compensation Survey finds that only 17 percent of civilian workers have access to paid family leave. 58 Indeed, nationally representative data from the Pew Research Center finds that 9 percent of respondents had an unmet need for leave to care for their own health, and 10 percent of respondents had an unmet need to take leave to care for a family member. 59 Higher-income workers are more likely to have access to paid leave than their lower-income counterparts. Pew reports that 74 percent of leave-takers earning $75,000 or more annually received payment during their leave. In contrast, only 38 percent of low-income leave-takers received payment, despite people with lower incomes being more likely to suffer from poor health than their wealthier counterparts. 60 The high variation in health across the socioeconomic spectrum, coupled with the existing upward skew of leave availability to those in higher-paying jobs, means that the demand for medical leave may vary sharply across the economic distribution.

A basic question encompasses the most relevant health-related research agenda for better understanding medical leave: How does paid medical leave impact individual health outcomes for those who take it? Currently, only a scattered few studies shed light on this question. For instance, a study assessing the effects of paid leave on health outcomes for nurses who experienced heart attacks found that those with access to paid medical leave were more likely than those without paid leave to return to work following recovery. 61 Yet a variety of factors limit the generalizability of this study to a broader set of conclusions regarding the health effects of paid medical leave. The small study size and specialized population (nurses with either angina or myocardial infarction) makes it too narrow to extrapolate broader conclusions. Moreover, the outcome variable studied—return to work—may not reflect a health-related outcome, given the myriad factors that come into the decision of whether to return to work following a health crisis.

More robust research looks specifically at the effects of universally accessible paid sick leave using U.S. data and finds that access to paid sick leave increases flu vaccinations by 1.6 million, which, in turn, leads to 63,800 fewer absences and 18,200 fewer health care visits due to illness. 62 Paid sick leave policy differs from paid medical leave along two key dimensions. First, sick leave typically guarantees access to a limited number of paid sick days, as opposed to the longer periods of time available under paid medical leave. Second, in the cases where public policy exists, paid sick leave is generally provided and paid for by employers because of a legal mandate that employers offer a minimum number of earned paid sick days to employees. 63 In contrast, all four states with paid family and medical leave policies have adopted a social insurance model funded by workers, employers, or both, and the policy design distinction likely results in meaningful differences in a variety of outcomes due to the differential treatment of both employers and employees. Nonetheless, the established connection between paid leave and health outcomes is a useful signal to both researchers and policymakers that lessening the trade-off between work and self care may have salutary outcomes for worker health, employers, and broader systems, including health care.

Substantially more evidence is needed to better understand the health effects of paid medical leave, including research that takes into account the varying potential lengths and intermittency of leave necessary for different medical conditions. More research also is necessary to understand the mechanisms linking paid medical leave and health outcomes. A variety of channels could explain the preliminary connections illustrated in the current research. For instance, does the health of workers improve because those on leave are able to seek care in a timely fashion or can afford access to the most appropriate course of treatment and/or continue to receive necessary regular treatments for recovery? Does health improve because paid leave allows workers to maintain a basic level of economic security while receiving treatment, which alleviates stress and contributes to overall well-being? 64 A future research agenda ought to take seriously the diverse literature on the determinants of health outcomes in order to grow the evidence on whether and how paid medical leave directly or indirectly contributes to better health outcomes for all.

Paid caregiving leave, similar to parental leave, has potential consequences for both the caregiver and the care recipient. A growing body of research documents the emotional and physical stress of caregiving responsibilities, particularly for those balancing the multigenerational care needs of both children and aging parents. 65 Recent survey research tells us that caregiving is a common experience. Nearly 17 percent (38.9 million) of all American adults are responsible for providing care to another adult. And about 34.2 million Americans have provided unpaid care to an adult age 50 or older in the past year. Women shoulder the majority of the adult caregiving burden (60 percent). A large majority of caregivers provide care for a relative (85 percent), and nearly half (49 percent) are caring for a parent or parent-in-law. 66 Families who lack access to paid caregiving leave face the dual strain of juggling work and care responsibilities along with the potential economic consequences that come with taking unpaid leave. 67 For part-time workers and those employed in small businesses, job-protected unpaid leave is not legally mandated under FMLA and thus workers in these positions are even more likely to face tough choices between work and caregiving responsibilities. 68

While research tells us a fair bit about the scope of the need for caregiving leave, the evidence on the impact of paid caregiving leave on caregivers is relatively scant. For instance, one study reports positive emotional health outcomes for parents caring for children with special needs who received caregiving leave, with higher positive outcomes for those who received paid caregiving leave compared to those for whom the leave was unpaid. 69 A second study suggests that paid leave combined with a supportive supervisor has powerful positive outcomes for caregivers’ emotional health, especially for women. 70 A focus group with family caregivers receiving benefits from state paid leave programs in California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island suggests that the income provided from the programs relieve stress and resulted in self-reported improvements to physical and mental health for caregivers. 71

These studies are a start to fill in the picture of the effects of paid caregiving leave, but many additional questions remain unexplored or underexplored. How does paid caregiving leave impact caregivers’ health outcomes? How does the impact of leave vary depending on the age, relationship, and health issue for the individual requiring care? How does access to paid leave impact caregivers across the economic spectrum? This last question is of particular interest, given that workers at the middle and bottom of the economic distribution are those who are least likely to have access to paid leave from their employers. More research investigating this is crucial for better understanding the potential consequences of a paid caregiving policy, particularly in light of the projected care needs of an aging U.S. population. According to the Population Reference Bureau, the number of Americans aged 65 and older is projected to more than double by 2060, and today’s older adults are more likely to need care than older adults in previous generations. 72

Paid caregiving leave also may impact the health outcomes of the individual receiving care from a family member. One study reports positive physical and mental health outcomes for disabled children whose parent(s) are able to take paid caregiving leave. 73 Research suggests that the role of the family caregiver has become all the more critical in light of the way health care is delivered, especially for acute illnesses requiring hospitalization. For instance, hospitalists—doctors with specialized training to provide care for acute illnesses in a hospital setting—provide the bulk of inpatient care. The expertise and consistent availability of a hospitalist has had important positive impacts, but continuity of care has suffered. Patients may not know who is in charge of their care and often do not remember their doctors’ names due to the constant shift-changes that bring new hospitalists in and out of a patient’s room over the course of hospital stays. As a result, families have found it necessary—and are often encouraged by physicians—to be present at all times in order to monitor medications, to insure that tests are carried out and results are received, to alert the rapid-response team if need arises, and, in general, to serve as a patient advocate in the context of a health care system that makes this all the more necessary. 74 The hypothetical connection between paid caregiving leave and patient outcomes is straightforward: If paid leave increases the prevalence of family caregiving, and family care improves patient outcomes, then paid caregiving leave is likely to have a direct impact on patient health. Yet, to date, research has not yet unpacked this story.

What do we know about the effects of paid family and medical leave on firm-level business and employee outcomes?

The growing number of companies offering paid family and medical leave as a benefit for employees suggests that firms understand the demand for paid time off for caregiving. At the same time, the well-publicized expansion of paid family and medical leave benefits is concentrated in high-growth industries and offered nearly exclusively to highly paid, highly educated professionals. Here’s just one of many cases in point: Netflix, Inc. announced a generous new paid parental leave policy for employees, but benefits were limited to only the salaried workers on the digital side of the business, excluding the thousands of hourly workers who do line work such as stuffing DVDs into envelopes. 75 The national statistics bear out this trend. In 2016, nearly one in four management and professional workers had access to paid family leave, compared to just 7 percent of service workers. 76

The Netflix example is emblematic of the persistent inequalities in working conditions in an increasingly polarized workforce and suggests that coverage for the workers who are least able to afford unpaid leave is unlikely to come from employers. It also raises questions regarding the consequences for firms of paid family and medical leave for their employees. In the case of Netflix, the extension of paid parental leave to digital employees was widely interpreted as a response to the low numbers of women in technology—by offering unlimited paid maternity leave to its highly compensated tech workforce, Netflix used the paid leave benefit as a recruitment and retention incentive for female employees. Does the research suggest that this is indeed the case—does paid leave help with recruitment and retention? Myriad other employer-side questions persist regarding paid family and medical leave as well. How does paid leave impact turnover costs, if at all? How does paid leave impact productivity, if at all? How do employers handle worker absences? And how do the answers to each of these questions vary depending on employers’ size, industry, occupational mix, and/or location?

Turnover and retention

The early survey-based research on the firm-level effects of paid family and medical leave from the states suggest that businesses generally view the policies favorably. 77 The existing state programs are funded by a small employee 78 payroll tax—generally between half a percent and 1.5 percent—and in return, workers taking leave have a share of their wages replaced by the state programs. Across the four states with existing paid family and medical leave policies (California, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island), employers report significant benefits and minimal costs.

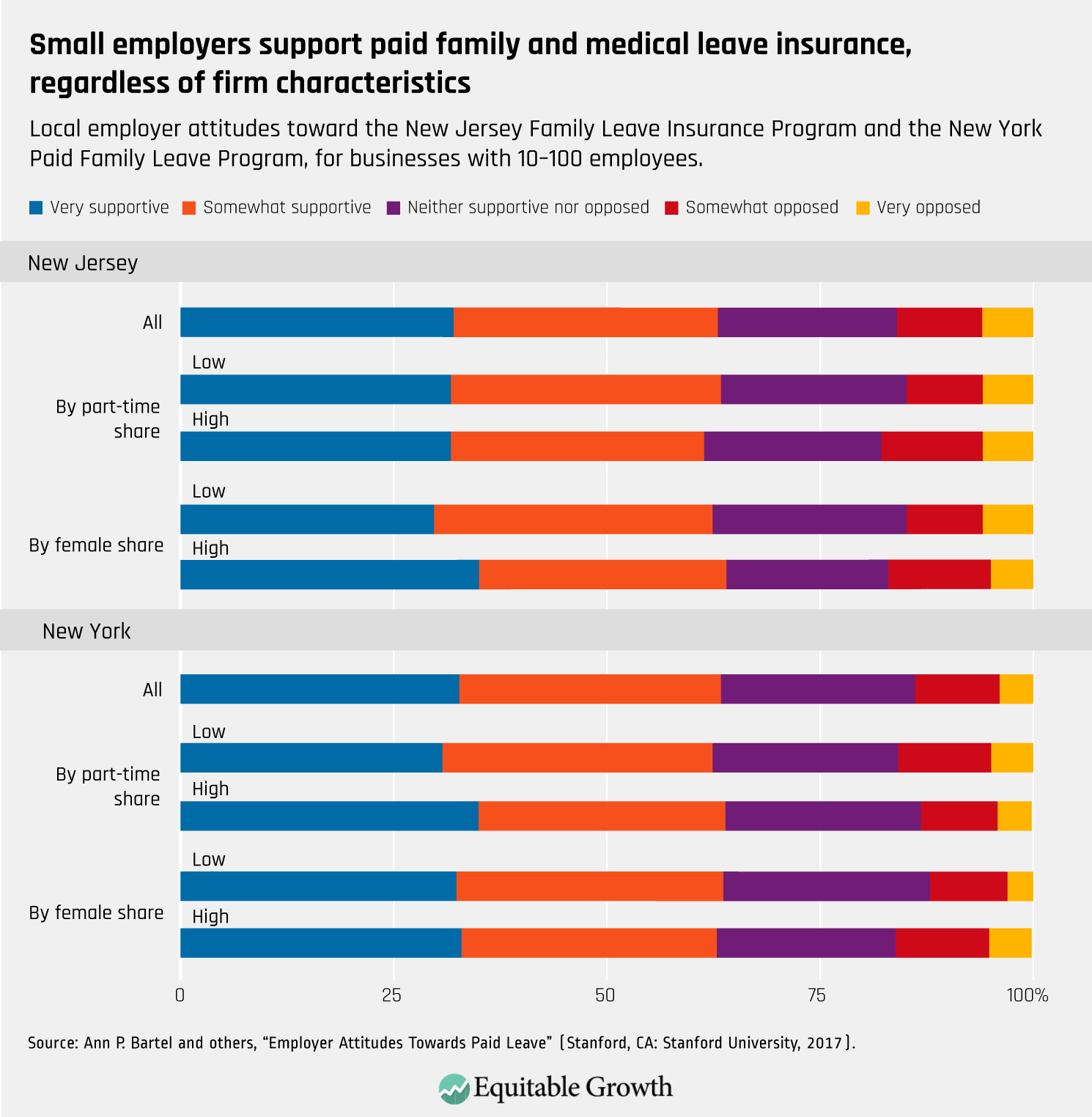

Survey-based research on California employers finds that the majority (86.9 percent) report no additional costs due to the state’s paid family and medical leave policy. 79 Research on Rhode Island employers similarly finds limited effects of the state paid leave policy on business, with employers noting few significant effects on business productivity and related metrics. 80 A recent study supported by a research grant from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth finds that 63 percent of small- to medium-sized employers in New Jersey and New York both reported that they supported or strongly supported paid family and medical leave programs. 81

More recent studies using administrative data from California bolster the results from the earlier wave of survey research in the state. Analysis of paid family and medical leave policy in California finds no evidence of higher turnover or a higher wage bill for employers over the decade-long period that the state policy has been in place. In fact, the opposite is true: The average California firm has a lower per-worker wage bill and a lower turnover rate now than it did before the paid leave policy was introduced. 82 Other research using both administrative and survey data from the states illustrates the efficacy of paid family and medical leave as a worker retention policy. 83 For instance, in a study utilizing California’s administrative data, the authors find that men and women who take leave and remain employed four quarters after the claim are more likely to have returned to their preclaim firm than to have moved to a new firm, regardless of the duration of their leave. 84

Turnover is expensive for businesses. If paid leave plays a role in reducing turnover, then the small short-term cost of covering an employee’s leave may result in substantial medium- and long-term rewards. Hiring and training a new employee is costly for managers, who spend less time on other productive activities as a result. And new workers require time to get fully up to speed in their new positions. Prior research on the cost of turnover suggests that replacing an employee costs about one-fifth of that worker’s salary, based on a combination of the cost of recruitment, selection, and training. 85 Early research from the states with paid leave programs suggests that paid leave can reduce worker turnover, which, in turn, means lower costs and higher productivity for business. Yet more research along these lines is crucial for better understanding the cost and benefits of paid leave for firms. How does the cost of turnover vary across industries and occupations? Does the cost of turnover vary across local labor markets? And is the cost of turnover higher in tight labor markets, thus meaning the retention benefits of paid leave are higher?

Covering for workers on leave

Employers need to cover for an employee who is out on leave, and early research suggests this is the most significant challenge faced by firms covered by state paid leave policies. The minority of California employers (13 percent) with additional costs reported that those costs came from the need for increased hiring and training expenses to cover for the employee out on leave. 86 Most employers covered for the employee on leave by temporarily reassigning the work of the absent employee to other employees, a finding echoed in research on the programs in Rhode Island and New Jersey. 87 While many Rhode Island employees report that a co-worker’s leave required them to take on additional job responsibilities, only 12 percent of those surveyed indicated that their co-worker’s leave had a negative effect on them. 88

A firm’s ability to cope with a temporarily absent employee is likely to vary based on firm size, as well as (potentially) industry, occupation, and the state of the local labor market. For instance, small firms are likely to have a more difficult time smoothing productivity when a worker is on leave because fewer employees means fewer remaining workers to spread around responsibilities in the absence of a colleague who is on leave. Research from Rhode Island suggests that small businesses require more from co-workers when an employee takes leave. 89 Employees at small businesses are more likely to report being asked to take on additional hours and/or to take on additional work duties. 90 Small businesses in Rhode Island also are more likely to hire a temporary employee to cover the leave-taker’s workload during his or her absence, as compared to large businesses. 91 At the same time, only a small minority (12 percent) of Rhode Island employees reported that a co-worker’s leave had a negative impact on their own work lives, suggesting that the policy did not create unmanageable challenges. 92

The impact of paid leave may also vary by industry and occupation. To date, we are not aware of any research answering this question utilizing U.S. data. A study utilizing Danish data suggests that large take-up rates of paid family leave among nurses led to higher hospital readmission rates and higher mortality rates for the elderly, presumably because hospitals were unable to replace the nurses on leave. 93 Additional research using data from the United States is needed to clarify the ways that employers cope with leave-based worker absences and how the impact of those absences varies across business size, industry, occupation, and other critical firm characteristics.

Distinguishing between parental, medical, and caregiving leave from the firm perspective

A third critical area in need of further research is the variation in the ways that different types of paid leave may impact firms. As discussed throughout this paper, parental, medical, and caregiving leave are distinct from each other in a variety of ways. Parental leave is relatively predictable, and the typical optimal duration of leave is relatively well-understood based on the physical and emotional health needs of both new babies and new parents. 94 Medical and caregiving leave are far less well-understood in terms of their predictability, duration, and intermittency. So, the nature of the work interruption stemming from a medical or caregiving leave is far less easily modelled than parental leave, which creates a challenge not only for firms but also for researchers seeking to understand the consequences of such leaves.

Moreover, different types of workers are in need of different types of leave at different points in time. For instance, young women of childbearing age are most likely to be in need of parental leave, second only to their partners. Men currently make up the majority of medical leave-takers in the state programs, as well as the majority of the population receiving long-term Social Security Disability Insurance benefits. 95 Prime-working-age women and older women are potentially more likely to need caregiving leave, given women’s persistent role as caregivers for both young and old family members. 96

Finally, other demographic characteristics may result in differing levels of demand for leave, with varying consequences for firms. For instance, the duration of leaves may vary by the earnings level of the worker. On the one hand, perhaps lower-earning workers are more likely to take longer leave because their social networks consist of few others who are able to go without pay to care for a loved one, and the cost of childcare and/or eldercare remains prohibitively high. On the other hand, perhaps lower earners are likely to take short leaves because a wage replacement rate of less than 100 percent means that even paid leave comes with meaningful consequences for family economic security. Low-earning workers and their families may also be in poorer health than higher-earning individuals, creating disparities in the demand for leave. Similar differences may play out across industries and occupations based on the mix of employees.

The high levels of variation in how leave may play out across employers—by type of leave, by employee characteristics, and by firm characteristics—is a compelling argument for a public universal program. Small employers, employers with high concentrations of low-skill, low-wage workers, and others are least likely to offer firm-provided benefits to employees because the cost of doing so would be quite high. In the absence of a public paid leave program, the cost of wage replacement for absent workers falls entirely on the firm. Yet diverse effects across types of firms persist even in the presence of a universal public paid leave program—the costs, consequences, and benefits may vary substantially across different types of firms. Further study utilizing the data from the states and other U.S.-based policy experiments would be immensely useful.

What do we know about the effects of paid family and medical leave on the economy as a whole?

The health of the U.S. economy depends on both households and firms. In other words, both household and firm dynamics affect supply and demand in important and often underappreciated ways, and the combined effects are what determine whether the economy is growing, who is benefiting from that growth, and the stability and durability of that growth. This basic point often gets lost in the day-to-day conversation about economic growth and stability, which too often focuses on short-term business performance and market fluctuations. Caregiving responsibilities impact economic growth and stability in important ways that are often relegated to a side-show conversation about “women’s issues”—if they are included in economic policy discussions at all. While this pattern has begun to change in recent years, more work remains to be done in order to make caregiving responsibilities a front-and-center economic policy issue.

Caregiving responsibilities play an important role in shaping labor supply through their impact on individual workers and families, as detailed in the above sections. The way that our society supports (or fails to support) the balance between work and care plays a powerful role in shaping who is able to contribute to the labor market, as well as what and when they are able to contribute. Caregiving responsibilities for workers also shape the labor demand side of the equation, as firms’ demand for labor is affected by factors such as productivity, turnover, and absenteeism.

Paid leave also may have important spillover effects on other policies, including existing public and private programs with important macroeconomic effects. These pieces come together to suggest that paid leave may impact not only individual health and labor outcomes and individual firm outcomes, but also boast the potential to shape economic growth and stability in important and understudied ways. A key takeaway worth highlighting up front is the need for more research on how all of these pieces of the puzzle fit together. The experimentation at the state level creates opportunity for more rigorous research clarifying how paid family and medical leave policies may be impacting broader economic growth and stability.

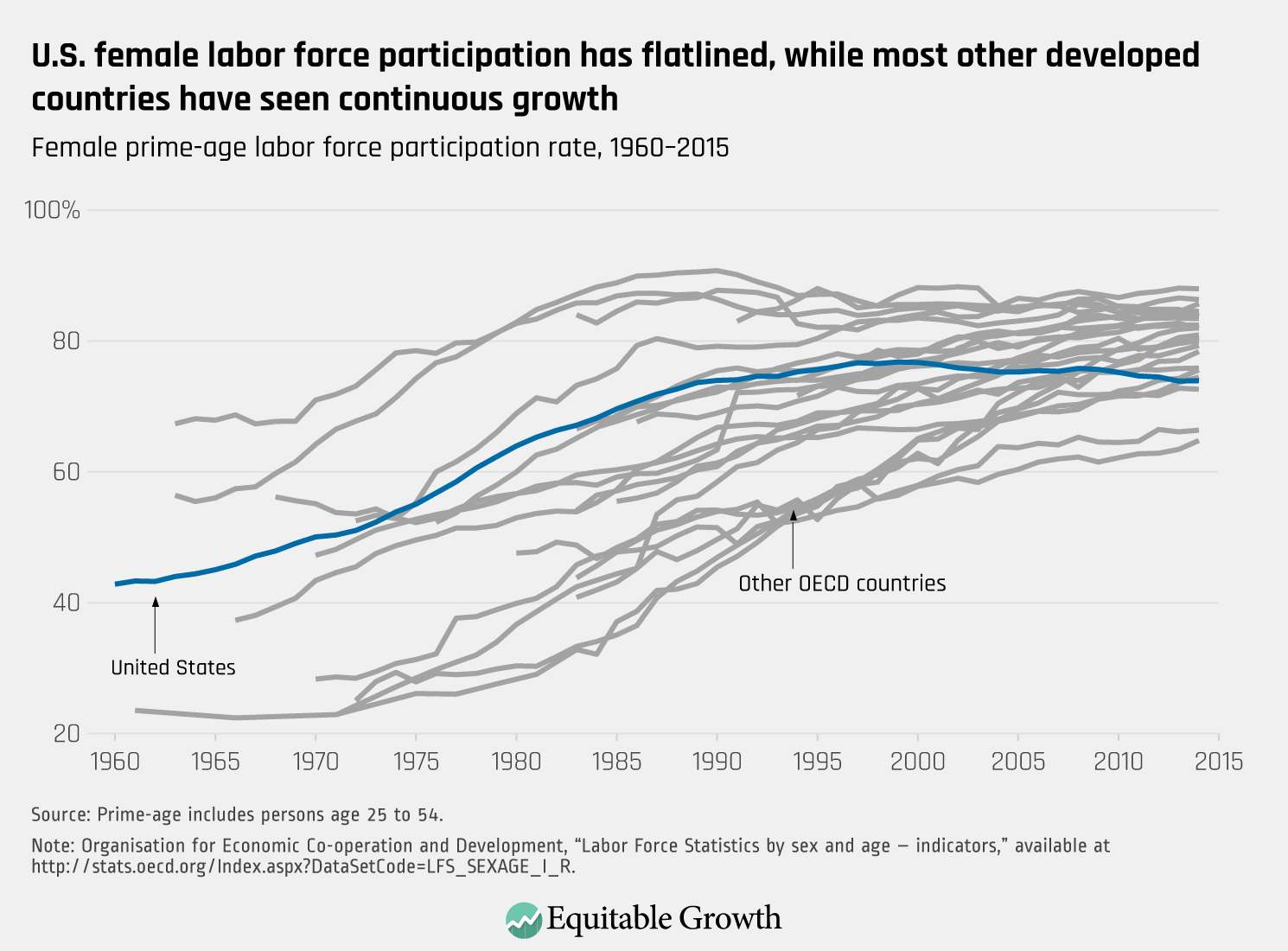

Labor supply

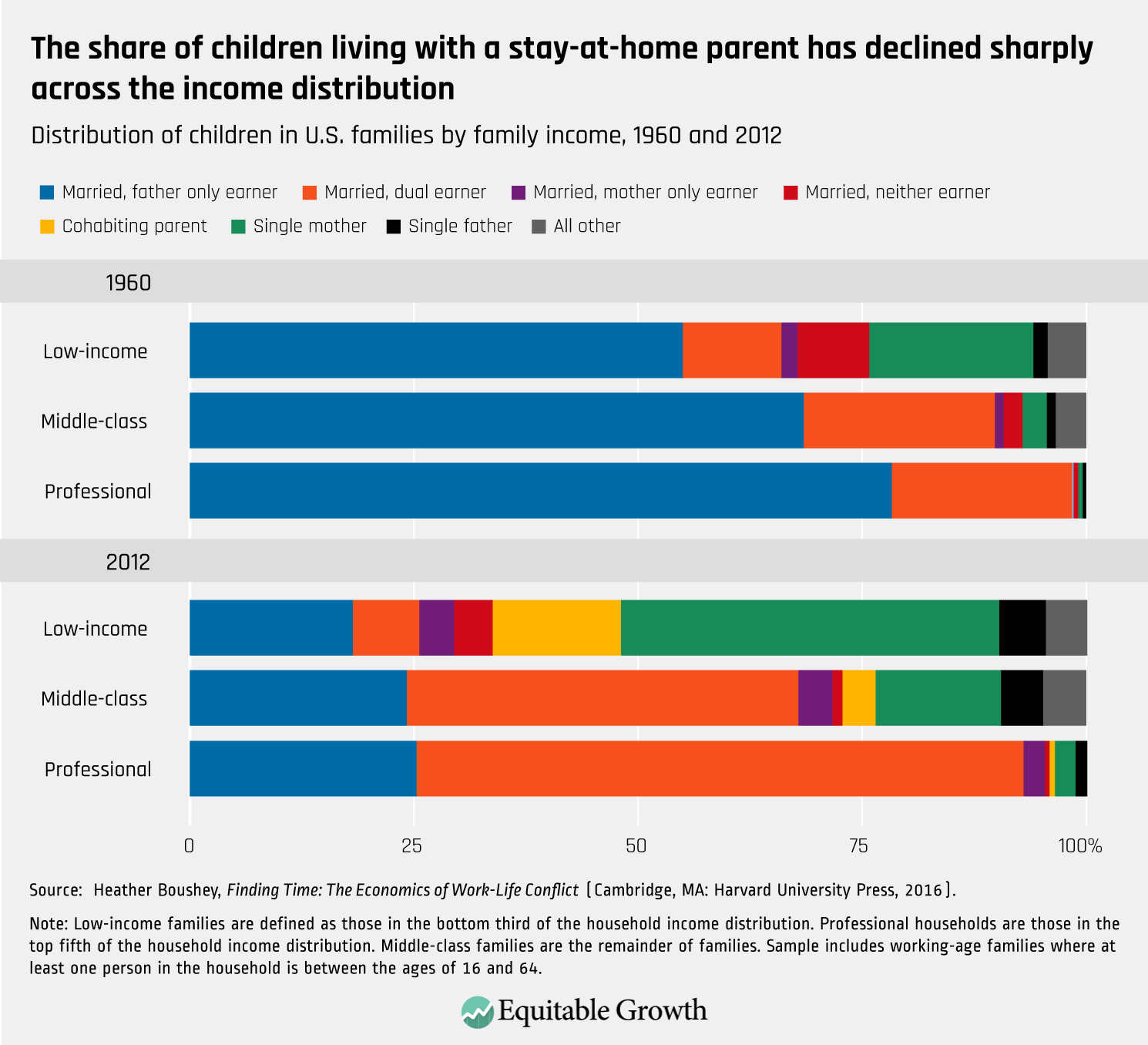

As noted in the earlier section on individual-level labor market outcomes for parental, medical, and caregiving leave, the research to date demonstrates compelling positive impacts of paid leave on labor supply, especially the benefits of paid parental leave for mothers’ labor supply. Labor force participation is a key ingredient for healthy economic growth. Decades of economic research demonstrates that per capita incomes increase as labor force participation increases, and until recently, the increase in women’s labor force participation has been the main engine for this growth. 97 After several decades of increases in women’s labor force participation, especially among mothers of young children, labor force participation rates for women ages 30 to 40 have decreased somewhat. 98 Research suggests that at least some of this plateau in women’s labor force participation rates is due to the failure of the United States to implement work-life polices—not only paid leave, but also childcare, flexible schedules, and other policies designed to help families better balance the demands of life at home and at work. 99 While early education and childcare stand out as policy arenas where improvements in the U.S. context would have a dramatic impact on women’s labor supply, paid family and medical leave also have an important role to play. 100

Early evidence from the states suggests that paid leave policies positively impact women’s labor supply in important ways, particularly for new mothers. Research using administrative data in California and New Jersey finds that paid parental leave in both of these states was associated with increased labor force participation for women around the time of birth, and this finding was driven nearly exclusively by the increased labor force attachment of less-educated women. 101 Other research relying on survey data finds that paid family leave in California was associated with a 5 percentage point to 6 percentage point increase in the probability that a mother is employed at 9 months postbirth, a finding that persists through at least the end of the child’s first year. 102

But one recent paper using survey data to examine the effects of California’s paid parental leave program finds that the increase in young women’s labor force participation was accompanied by an elevated unemployment rate and longer durations of unemployment for young women. 103 While this finding could be interpreted in various ways, one parsimonious possible explanation for the increased unemployment rate and duration is that the increased labor supply generated by the paid leave policy was not met with a sufficient immediate increase in labor demand to accommodate the additional workers who entered the labor market as a result. Future research ought to study the dynamics of labor supply and potential unintended consequences as a result of paid leave policies, with special care to take into account local labor market conditions over an appropriate time horizon to allow for equilibrium.

The current scholarly literature tells us virtually nothing about the impact of paid family and medical leave on men’s labor supply. Research on mother’s labor force attachment has not been accompanied by work on father’s labor force attachment, perhaps because the number of men taking parental leave remains relatively low even after the implementation of paid leave policies (one study of California’s parental leave policy finds that the policy significantly increased rates of father’s leave-taking from about 2 percent to about 3 percent). 104 Nonetheless, better understanding the impact of paid leave policies on men’s labor supply is a critical question. Paid parental leave may encourage men to take additional time to bond with their children, and fathers’ demand for leave may continue to grow: Fathers today spend dramatically more time caregiving than was the case in the previous generation. 105

In addition, and perhaps most importantly, the existing research tells us virtually nothing about the effects of medical or caregiving leave on labor supply. The existence of Temporary Disability Insurance programs providing short-term wage replacement for individuals in need of medical leave in the four states that have now built on those programs to create a more expansive paid family and medical leave policy creates the opportunity to study the impact of medical leave on labor force attachment over the course of several decades (or more, in the states where temporary disability insurance has existed for nearly a century). 106 The layering of caregiving leave on top of existing TDI programs in the states creates the opportunity for research exploring the impact of caregiving leave on labor force attachment. 107 Survey research on the effects of caregiving demands on workers suggests that the absence of paid caregiving leave means that workers are retiring earlier than anticipated, and, as a result, are sacrificing Social Security and private retirement savings. For instance, one recent survey finds that 22 percent of retirees left the workforce earlier than planned because a family member needed care. 108

In general, more research is needed about how paid leave for both one’s own illness and for caregiving is affecting labor supply, with a particular focus on whether it is concentrated at the low or high end of the wage spectrum and how the consequences are distributed across the age profile of workers.

Fiscal savings

The absence of a widely available, national, public paid family and medical leave policy also has potential implications for the nation’s fiscal picture. Caregiving comes with costs that may be shifted onto other public programs. The costs of delayed medical intervention, for example, may result in more expensive health care costs in the long term, with implications for public programs such as Medicare and Medicaid. Early retirements by caregivers unable to balance work and family may result in stress to the Social Security retirement system. Labor force exits due to disability may result in elevated Social Security Disability Insurance applications and elevate costs to taxpayers, with long-term consequences for both SSDI costs and for labor force participation among individuals on the margins of the labor market.

A small but growing literature focuses on questions relevant to this line of inquiry. For instance, one study finds that paid family leave reduces applications to other social safety net programs, with women returning to work following a paid maternity leave having a 39 percent lower probability of receiving public assistance and a 40 percent lower chance of receiving Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits (commonly known as food stamps) in the year following a child’s birth, compared to those who took no leave at all. 109 But more rigorous research investigating the links between family’s unmet caregiving needs and existing social programs is critical for understanding the full economic impact of paid family and medical leave policies. Examples of important future lines of inquiry include program interactions with public disability policies, health care policies, and long-term care policies.

Social Security Disability Insurance

The link between paid medical leave and the Social Security Disability Insurance program is perhaps the first and most obvious connection that demands further exploration. If workers had access to temporary disability benefits that allowed them to continue to receive a substantial share of their wages while they recuperate from a serious medical condition, then would those facing such conditions stay in the labor force rather enrolling in SSDI? Could the introduction of temporary disability benefits help reduce the duration of SSDI benefits among those who do ultimately enroll?

An extensive body of research documents the ways that SSDI may discourage the return to work among individuals with work interruptions due to disabilities, and the program is “sticky,” meaning that most eligible enrolled recipients do not return to the labor force once qualifying for benefits, regardless of age. 110 In particular, SSDI requires that applicants reduce labor force participation to keep their earnings under a certain threshold for a 5 month period in order to qualify for SSDI benefits. Following qualification, beneficiaries begin a 9 month trial period that allows them to exceed the earnings threshold in order to test whether they can return to work, after which a short grace period ensues and individuals with wages above the threshold are cut off of SSDI benefits. The result is a system with rigorous requirements for enrollment in SSDI, but also one that potentially discourages work among those who have no choice but to reduce labor force participation while waiting for an eligibility decision.

Disability rates in the United States are remarkably high. By age 50, the average working male American has a 36 percent chance of having experienced disability at least temporarily during his working years. Chronic and/or severe disability comes with serious economic consequences, including a 79 percent decline in earnings, a 35 percent decline in after-tax income, and a 24 percent decline in food and housing consumption. Research consistently finds that individual savings, family support, and existing social insurance programs play a “partial and incomplete” role in reducing the consumption drop that follows disability. 111 Thus, efforts to support workers in their efforts to both care for their own major medical needs, while simultaneously maintaining their economic well-being and potential participation in the labor market going forward is an issue likely to touch a remarkably high share of the labor market. This is only likely to grow as the workforce ages.

Recent studies exploiting variations in SSDI program examiners (the judges who determine whether an individual qualifies for SSDI based on the severity of his or her health condition) suggests that marginal individuals’ labor supply decisions are strongly influenced by the availability of SSDI benefits. Specifically, one study finds that 23 percent of SSDI applicants are on the margin of program eligibility, meaning their receipt of SSDI was conditional on their program examiner. 112 Of that group, employment would have been 28 percent higher in the absence of SSDI receipt 2 years after the initial eligibility determination, and average individual earnings for this group would have been about $3,800 to $4,600 higher per year. Compared to the nonmarginal SSDI recipient, marginal recipients were likely to be younger, more likely to have a mental disorder, more likely to have earnings in the bottom of the earnings distribution, and more likely to have higher medical costs and longer program enrollment duration.

Prior research suggests that access to other social safety net and social insurance programs affects SSDI application rates. For instance, unemployment insurance recipients are less likely to apply for SSDI than similarly situated individuals who are not eligible for unemployment benefits. 113 If access to paid medical leave could play a role in supporting labor force attachment for these marginal SSDI applicants, then the lifetime earnings and employment outcomes for individuals and their families could be improved. Moreover, the additional labor force attachment fostered by a paid medical leave program could significantly relieve fiscal pressures on SSDI, which faces serious funding challenges due to higher-than-anticipated enrollment and continued program costs.

The existence of Temporary Disability Insurance Programs in the handful of states that have built their paid family and medical leave programs on this system’s foundation provide a helpful starting place for researchers interested in exploring the potential relationship between paid temporary medical leave, earnings and employment, and SSDI. One promising research project from a team of researchers at the University of Massachusetts Boston is exploring this relationship in a new project supported by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, but additional creative work is necessary to build out the knowledge base on how temporary medical leave programs might interact with the SSDI program. 114 Given the role that SSDI’s fiscal challenges play in debates over the financial stability of the Social Security system as a whole, this research is particularly important and likely to have an audience that reaches beyond those interested in caregiving to include scholars and policymakers more interested in questions of fiscal responsibility and budget.

Health care

Paid leave also may have important effects on the use of preventative care, as well as on the provision of timely medical care with better health outcomes, with implications for health care costs across a variety of programs and policies. Early research suggests that access to paid sick leave—distinct from paid medical leave, which provides leave for serious medical illnesses, as opposed to sick days for episodic minor illnesses such as the flu—results in patients seeking and receiving more effective preventative treatments (including flu shots and pap smears) and fewer patients visiting emergency rooms for medical care. 115 One study suggests a connection between an individual’s access to paid family and medical leave and the likelihood of receiving a flu shot. 116

While these early studies provide good reason to hypothesize positive outcomes for paid family and medical leave on broader health systems outcomes more generally, more research is needed to connect the dots between the individual- and family-level health outcomes, including those detailed at length above, and the overall systemwide consequences of improved health on both economic performance and on health care systems savings. 117 Moreover, the public health crisis of opioid addiction is one that may overlap substantially with the need for both paid medical leave and paid leave for family caregivers.

Taken together, the impact of paid family and medical leave may have meaningful consequences on health care, including health care costs, delivery, and efficacy, with macroeconomic results as well. For instance, researchers focused on the value of reducing infant mortality rates in the United States calculate a back-of-the-envelope figure suggesting that reducing infant mortality to the rate of Scandinavian countries would be worth approximately $84 billion annually. 118 Given the emerging literature suggesting the role that paid parental leave can play in reducing infant mortality, the economic “cost” of paid family and medical leave deserves to be reconsidered in terms of potential benefits using these new tools and techniques.

Long-term care

Finally, paid caregiving leave may have important interactions with long-term care needs—an issue of growing importance as the U.S. population ages. Of course, paid leave will not solve the larger issue of long-term care needs in the United States—the challenges of long-term care in the context of an aging population and a broken health care system are well beyond the reach of any temporary paid family and medical leave policy. Yet providing caregivers with leave that allows for the coordination of an ill loved-one’s care may be an important piece of that puzzle, with ripple effects that touch not only the recipient of care and the caregiver but also the broader economy.

Recent research on the impact of California’s paid leave policy on nursing home utilization finds that paid leave led to an 11 percent reduction in the share of the elderly residing in nursing homes. 119 While the study does not allow for a test of a specific mechanism connecting paid leave to nursing home utilization, the authors hypothesize that paid caregiving leave allows family members to provide timely care to aging relatives, which, in turn, reduces the need for long-term institutionalization. Specifically, access to temporary paid leave for caregiving may allow for timely, engaged responses to assist with rehabilitation from acute incidents (postsurgical rehabilitation and early interventions for dementia and Alzheimer’s), which, in turn, eliminates or delays the need for long-term institutional care.

The results of this research suggest that paid caregiving leave may not only provide valuable resources for families but also improve the broader fiscal picture—and thus the economy as a whole. Nursing home care accounts for the largest share of long-term care costs in the United States, which strains both family budgets and public finances. Medicaid—a joint state-federal program financed largely by the states—is the primary payer for 62 percent of nursing home residents, some of whom deplete their assets in order to become eligible for the program. Medicare, which is fully federally financed and mainly covers the cost of hospitalization following an acute incident, covers about 15 percent of nursing home utilization overall. In addition to the serious strain long-term care places on state and federal budgets, it is not especially popular. The majority of seniors prefer to receive family- or community-based care and to remain at home (or in a family member’s home). 120

While the California study is a start, more research is needed on the connection between paid family and medical leave and the challenges that long-term care presents for both families and the nation’s fiscal outlook. The California study also highlights the need for access to meaningful data on a host of related issues underlying the questions involved. Connecting the dots between Medicaid usage and paid family leave was a substantial challenge for the authors and one that requires administrative data linking multiple program usage, medical outcomes, labor market outcomes, and demographics over a substantial period of time. This kind of longitudinal administrative data is far too rare, yet it is a prerequisite for developing the empirical knowledge base for understanding the complex relationships between public programs, family economic well-being, and broader economic outcomes.

Adding up the pieces: Paid leave and economic growth

Labor supply plays a key role in spurring economic growth. Healthy, growing economies are typically characterized by high (and/or growing) rates of labor force participation. While no direct evidence links paid family and medical leave to increases in Gross Domestic Product in the United States, the research on the labor supply effects indirectly translates into a story about GDP worthy of mention here. Women’s increased labor force attachment and educational attainment accounts for nearly all of the growth in middle-class incomes since 1970. 121 The compelling evidence to date on the impact of paid leave on women’s labor supply suggests good reason to believe that paid leave will translate into salutary GDP outcomes as well. 122

Data from the states suggest that the main source of demand for paid leave is not for parental leave but rather for medical leave to tend to one’s own serious illness. 123 If paid medical leave has similar labor supply effects as does parental leave for workers with health conditions across the life cycle, then the potential for large economic benefits through the labor supply channel is high. Looking ahead, researchers ought to focus on the long-term labor supply effects of paid medical leave in order to broaden the empirical evidence on whether and how paid leave to care for one’s own illness shapes labor force attachment and long-term earnings outcomes.

In addition, the current number of claims for caregiving leave are relatively low and the research on the labor supply effects of paid caregiving leave on caregivers (as well as care recipients) is scant, yet it is entirely possible that caregiving leave could have substantial labor supply effects as well, especially on a national scale. While there were an estimated 4.45 million caregivers in California in 2013, in the 2013–2014 fiscal year, only 27,306 caregiving leave claims were filed, which indicates that the program is underused. 124 If take-up rates for caregiving leave were to increase, then there could be substantial effects on labor force attachment or other long-term labor supply outcomes. To date, research has not systematically investigated how caregiving leave affects the labor supply. 125

The wide variety of types of conditions for which an individual worker might take a medical or caregiving leave means that researchers ought to pay particular attention to differing medical conditions, differing caregiving relationships, and the potential for demographic characteristics such as earnings, occupation, industry, geography, race, and age to shape outcomes. While this complex constellation of issues makes modelling the effects of medical or caregiving leave on growth a challenging exercise, continued attention to such issues is paramount.

Finally, it is worth noting that GDP is only one way to study the growth of the economy as a whole. Researchers ought to give serious thought to other metrics that might meaningfully capture the macroeconomic effects of paid family and medical leave policies. For instance, the Disaggregating Growth project at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth supports the development of growth statistics that demonstrate how gains in GDP are distributed across the income distribution. 126

Conclusion

The tension between work responsibilities and caregiving responsibilities is not going away anytime soon in our country. Babies will continue to be born, workers will continue to become ill, and the aging population will continue to grow the demand for eldercare. The majority of families will not be able to count on a stay-at-home caregiver in the future. Many American women have been working and caring for families simultaneously for decades. Men are taking on a somewhat greater share of caregiving (and policy design may encourage that trend), but policymakers certainly shouldn’t expect men to fill the role that women once played as caregivers for both the young and old. Caregiving needs in the United States are shining a bright light on the threadbare parts of our existing safety net, and we are seeing the economic consequences of this daily.

Existing academic literature already tells us a great deal about how paid leave for the full scope of caregiving needs can shape individuals, families, firms, and broader economic outcomes. Indeed, the knowledge base on parental leave is sufficient to have brought about a bipartisan, cross-ideological consensus on both the scope of the problem and the basic contours of a proposed federal policy solution for paid parental leave. 127 The same cannot be said for paid medical and caregiving leave, which highlights the need for additional research on these elements of the caregiving puzzle. 128 Despite that absence of consensus, a host of research suggests that the demand for both medical and caregiving leave is real. Moreover, multiple states have implemented successful policies to date, all utilizing the same social insurance-based model covering not only parental but also medical and caregiving leave.

While the foundational research is strong, we have a great deal left to learn. Currently, the economics of paid leave are generally discussed in terms of costs, with the benefits of leave narrowly construed in individual or family outcomes. Yet these individual and family outcomes add up to a broader economic narrative—a host of promising research remains to be done in order to broaden the conversation, beginning with how paid leave could be defined as a public good, rather than a cost.