We can cut child poverty in the United States in half in 10 years

Over the past 50 years, the number of U.S. children living in poverty has been cut in half—a tremendous accomplishment. Yet nearly 10 million children, or 13 percent of children residing in the world’s richest country, still live in poverty. This includes more than 2 million kids living in deep poverty. High levels of child poverty are shameful and lead to bad outcomes for our country. The good news is that substantial further reductions in child poverty are within reach.

In 2015, the U.S. Congress asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to conduct a thorough study of child poverty in our nation and to focus on policies that had the potential to cut the number of children living in poverty in half within 10 years. The Academies put together a team of economists, policymakers, and experts on child welfare to tackle this bold mandate. I was honored to participate, and I am excited about the final product and the roadmap it can provide to policymakers interested in prioritizing child poverty.

To provide context, Congress asked that we first study the impacts of child poverty on children’s well-being and evidence about the effectiveness of current programs intended to support children and families. The committee was directed to use the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which is constructed by the U.S. Census Bureau and includes the effects of most anti-poverty programs. (The official poverty measure does not include the effects of most anti-poverty programs, and so it cannot be reduced by expanding anti-poverty programs.) In 2015, the poverty line for a two-parent, two-child family was $26,000 in annual income; the line for deep poverty was half that.

Beyond compassion for those experiencing difficult circumstances, why should those of us who do not live in poverty care about the children who do? Because child poverty affects all of us. Although there are always exceptions, on average, poor children develop weaker language, memory, and self-regulation skills. When they grow up, they have less income, on average, and therefore pay lower taxes. Poor children are also more likely to grow up to be more dependent on public assistance and have more health problems, and are more likely both to commit crimes and to be victims of crimes. And, as the National Academies report concludes, the weight of the evidence is that it is low income itself that causes these outcomes, especially when poverty occurs in early childhood or persists throughout a large portion of childhood.

There are real economic costs to this lost productivity. Estimates range from 4 percent to 5.4 percent of Gross Domestic Product, or approximately $1 trillion annually (based on the size of the U.S. economy in 2018). So, nonpoor Americans should think of child poverty not as a problem that happens only to other people but as a challenge facing all of us.

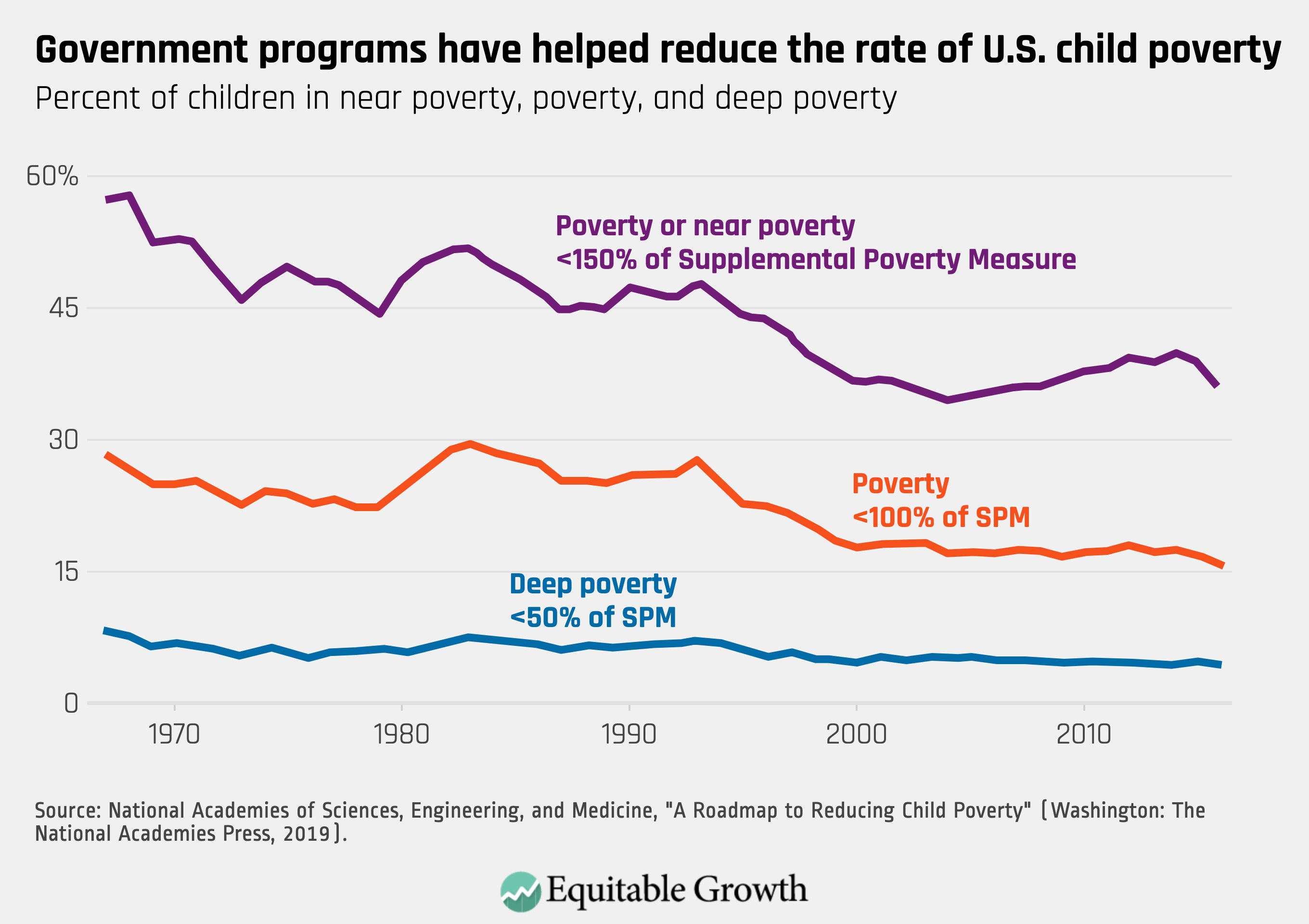

According to the Supplementary Poverty Measure, the child poverty rate in the United States fell from 28.4 percent to 15.6 percent between 1967 and 2016. The causes of these reductions are much debated, but it is clear that government tax and transfer programs—specifically, increases in government benefits intended to reward work or provide support to those in need—played a significant role not only for those classified as living in poverty or deep poverty, but also for those in near poverty, which is 150 percent of the poverty line. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The broad impact of some key programs has been clear. Periodic enhancements of the Earned Income Tax Credit—a refundable tax credit that rewards work by reducing taxes and providing payments for low-income working families—have improved child educational and health outcomes and increased maternal employment. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program has improved birth outcomes and improved children’s and adults’ health. And expansions of public health insurance for pregnant women, infants, and children have led to substantial improvements in child and adult health, educational attainment, employment, and earnings.

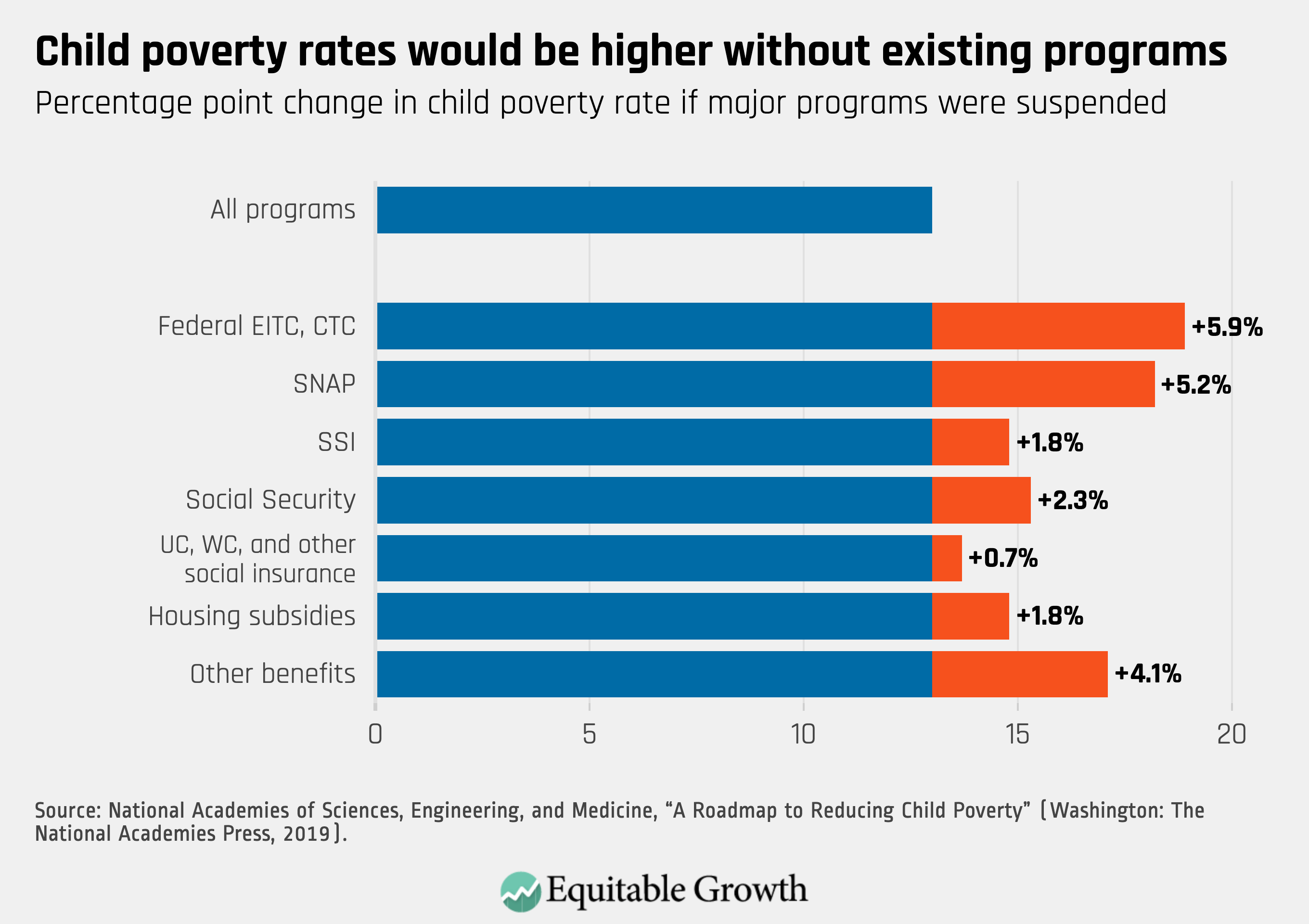

The success of these programs is undeniable. Eliminating the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit (a per-child, refundable tax credit for families), for example, would raise the current child poverty rate by almost half—5.9 percentage points—from 13 percent to nearly 19 percent. Eliminating Supplemental Nutrition Assistance would raise the rate by 5.2 percentage points. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

The evidence is clear: Governmental actions can and do reduce child poverty. There is, however, no one program—no silver bullet—that can accomplish the goal of cutting child poverty in half. But it is possible to assemble arrays of policies that can cut the rate of child poverty by half over the next decade.

The recommendations of the National Academies report

The report by the National Academies does not prescribe a particular path, but rather provides a menu of options for policymakers. We put together four illustrative packages of programs, with varying combinations of work incentives and family supports. One package would cut child poverty in half, one would cut both child poverty and deep child poverty in half, and two smaller packages would cut child poverty by a more modest amount. In addition to reducing poverty, all of these packages would incentivize work by raising take-home pay and reducing the costs associated with employment.

The first package, which would cut child poverty rates in half by relying on a combination of means-tested supports and work incentives, would:

- Increase payments for the Earned Income Tax Credit for the lowest-income and mid-range recipients of the credit

- Convert the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit to a fully refundable credit and concentrate its benefits on families with the lowest incomes and with children under the age of 5

- Increase Supplemental Nutrition Assistance benefits by 35 percent and increase benefits for older children

- Increase the number of housing vouchers for families with children to increase significantly the number of eligible families who would use them

The second package, which would provide more universal benefits, would cut both overall child poverty and deep child poverty rates by half with a combination of work incentives, economic security programs, and social inclusion initiatives. It includes two programs, which would be new to the United States. This package would:

- Increase payments for the Earned Income Tax Credit by 40 percent across the board, continuing to phase it out at the current income levels

- Convert the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit to a fully refundable credit and concentrate its benefits on the lowest-income families and families with children under age 5

- Raise the federal hourly minimum wage from the current $7.25 to $10.25 and index it to inflation

- Restore eligibility for legal immigrants for several means-tested economic security programs, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Medicaid, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

- Create a new child allowance of $225 per month per child for families of all children under age 17, including legal immigrants

- Institute a child support assurance policy to provide a backup source of income to custodial parents if the other parent does not pay child support, and set a guaranteed minimum child support amount of $100 per month per child

A third package would expand the Earned Income and Child and Dependent Care tax credits, while adding a $2,000 child allowance to replace the current Child Tax Credit. This package would reduce child poverty by an estimated 36 percent. A fourth package, which included only four “work-oriented” programs (the Earned Income and Child and Dependent Care tax credits, an increase in the minimum wage, and a nationwide roll-out of a promising demonstration program called “Work Advance”), was estimated to have the largest effects on the employment of low-income workers but the smallest effect on reducing poverty (a reduction of 18.8 percent). This simulation illustrates how hard it is to reduce child poverty only through encouraging parents to work. There are far too many full-time jobs that, without other assistance, leave parents and children in poverty.

These packages—which, again, are intended only to be illustrative—range in estimated cost from $8.7 billion to $108 billion, with the higher-cost programs having the greatest impact on child poverty. Specifically, the “means-tested” package would cost $90.7 billion annually. It would add an estimated 400,000 individuals to the job rolls, with earnings of $2.2 billion annually. The “universal” package would cost $108.8 billion and increase employment by more than 600,000 jobs and add $13.4 billion in earnings. The third package, which would only partially achieve the poverty reduction goal set by Congress, as discussed above, would cost $44 billion annually; it would increase the number of job-holders by 568,000. Finally, the “work-oriented” program would cost only $8.7 billion and would add more than 1 million jobs, but would lead to relatively modest reductions in child poverty.

The estimates are based on federal tax law in 2015, which was in effect for most of the preparation of the report, though additional simulations show that the new tax law did not radically alter the conclusions. The groupings of programs are intended to show how policymakers could “mix and match” policies. Other packages could be simulated by adjusting individual package elements to achieve specific cost levels, poverty reductions, and levels of new jobholders.

The report’s findings are evidence-based. We carefully reviewed existing research to estimate the effects of child poverty, how current programs are working, and what programs would work. The ideas are nonpartisan, and some programs that would be enhanced have historically enjoyed bipartisan support. We understand that many policymakers are disinclined to increase spending, but they ought to consider the economic and fiscal costs of child poverty, in addition to the personal and social costs—the estimated $1 trillion loss in GDP mentioned above suggests annual losses to the U.S. Treasury well in excess of the costs of these proposed initiatives. These measures truly would pay for themselves and more.

Areas for further research recommended in the National Academies report

Congress also asked us to suggest areas where additional research could advance the knowledge necessary to develop policies to reduce child poverty. One important area where more research is needed concerns the effectiveness of work requirements on participants in anti-poverty programs. The existing research on this question largely pertains to the 1996 welfare reform (the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, which created the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program). It is thus not only very dated but also muddied by the many other changes in welfare systems that were embedded in the new law or took place at around the same time.

One case in point: The passage of the 1996 welfare reform legislation was followed by large increases in the employment of single mothers, but the evidence suggests that expansions in the Earned Income Tax Credit and the booming economy—not the work requirements enacted as part of the 1996 welfare reform law—were largely responsible for these gains. The National Academies report thus calls for high-quality, methodologically rigorous research and experimentation on the effectiveness of work requirements today and more generally, on ways to boost the job skills and employment of parents in low-income families receiving public assistance.

A second research issue highlighted in the report is that we need better measures of poverty itself. One example is public health insurance. Although a great deal of the support offered to low-income children comes in the form of the health insurance offered through Medicaid and the Child Health Insurance Program, the effects of health insurance are not properly incorporated into poverty measures. Hence, by construction, even very large expenditures on Medicaid cannot have any impact on measured poverty.

A second example is the lack of a consensus on how best to measure consumption poverty. Despite the view of many observers that it would be more reasonable to assess poverty using measures of consumption rather than measures of income, there is currently no effective tool for doing so. This is an active area for research, including work by Equitable Growth grantee Tim Smeeding, the Lee Rainwater Distinguished Professor of Public Affairs and Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a member of our National Academies study.

A third example is the weak existing measurement of poverty in small ethnic, racial, and demographic groups. Although we know that some groups such as Native Americans are disproportionately likely to suffer poverty, current data sources yield only small samples of these groups, which makes it difficult to study determinants of poverty or the effects of anti-poverty programs among them.

Conclusion

While the National Academies report responds to the 2015 congressional mandate, which set the clear and specific goal of cutting child poverty in half in 10 years, one could also imagine other longer-term approaches to addressing the societal problems associated with child poverty. Investments in early childhood education, for example, would not reduce child poverty immediately but have been shown to make it less likely that children will grow up to be poor or that their children will be poor.

The model used to create these estimates in the report was developed by the respected Urban Institute, which would be fully capable of estimating other proposals and packages. Of course, Congress can also use the Congressional Budget Office to obtain its own estimates, and I hope this will indeed happen. That would mean that Congress is giving the report the serious consideration it deserves.