On July 11, the National Bureau of Economic Research kicked off its summer institute, an annual 3-week conference featuring discussions and paper presentations on various topics in economics, including disaggregating income growth, labor market outcomes of technological innovations, and welfare implications of regulating tech companies. This year’s NBER event is virtual and is being livestreamed on YouTube.

We’re excited to see Equitable Growth’s grantee network, our Steering Committee, and our Research Advisory Board and their research well-represented throughout the program. Below are abstracts (in no particular order) of some of the papers that caught the attention of Equitable Growth staff during the second week of the conference.

Check out the round-up from week 1, and come back next week for the round-up from the third and final week.

“Real-Time Inequality”

Thomas Blanchet, University of California, Berkeley

Emmanuel Saez, University of California, Berkeley and NBER, former Steering Committee member

Gabriel Zucman, University of California, Berkeley and NBER, Equitable Growth grantee

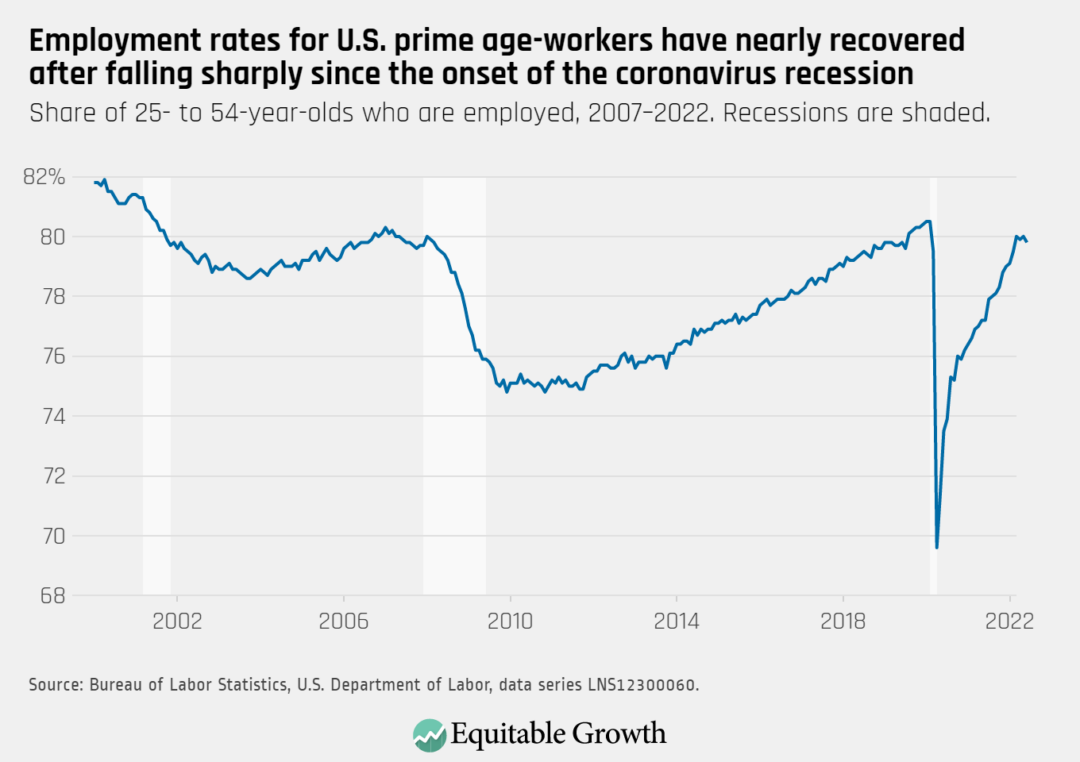

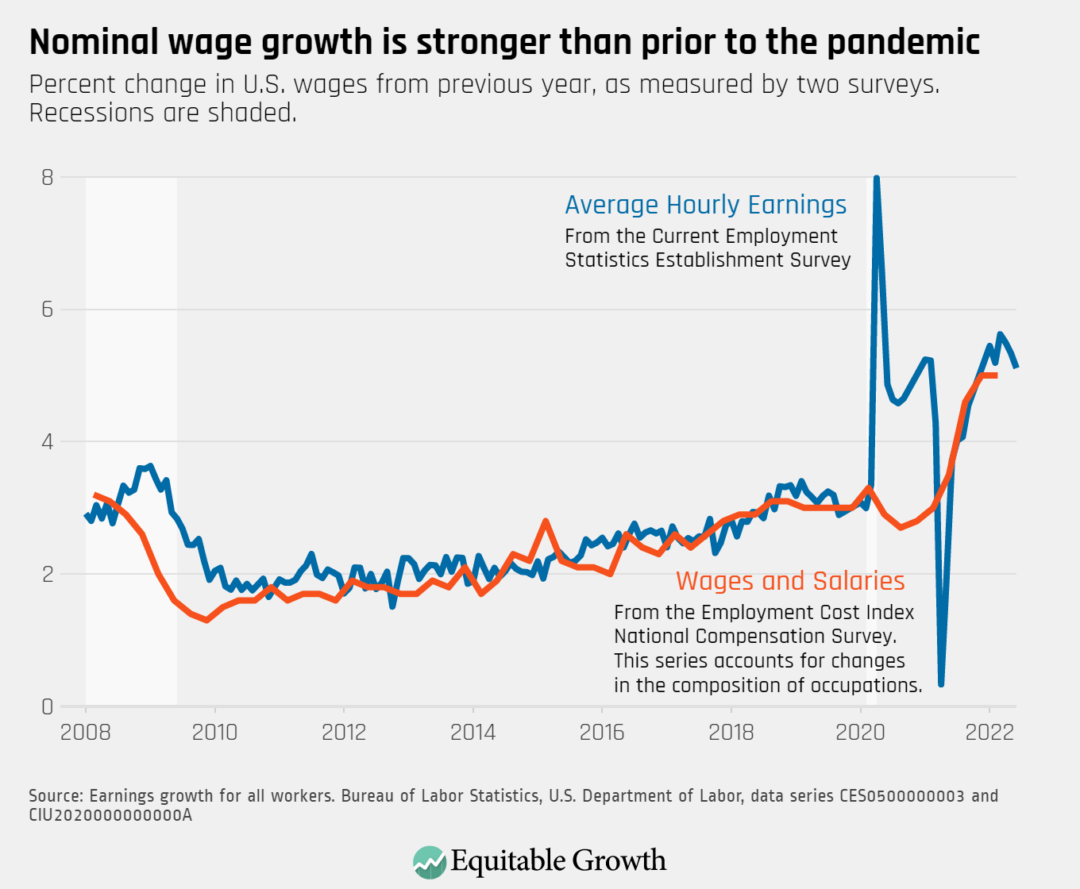

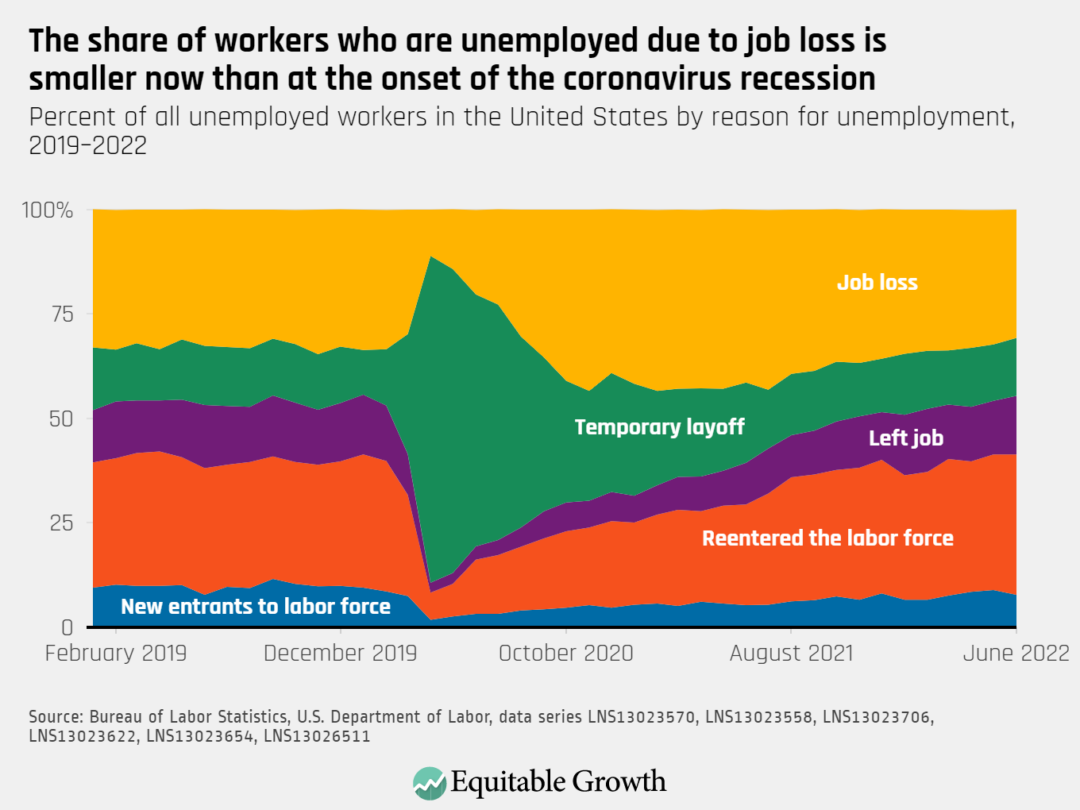

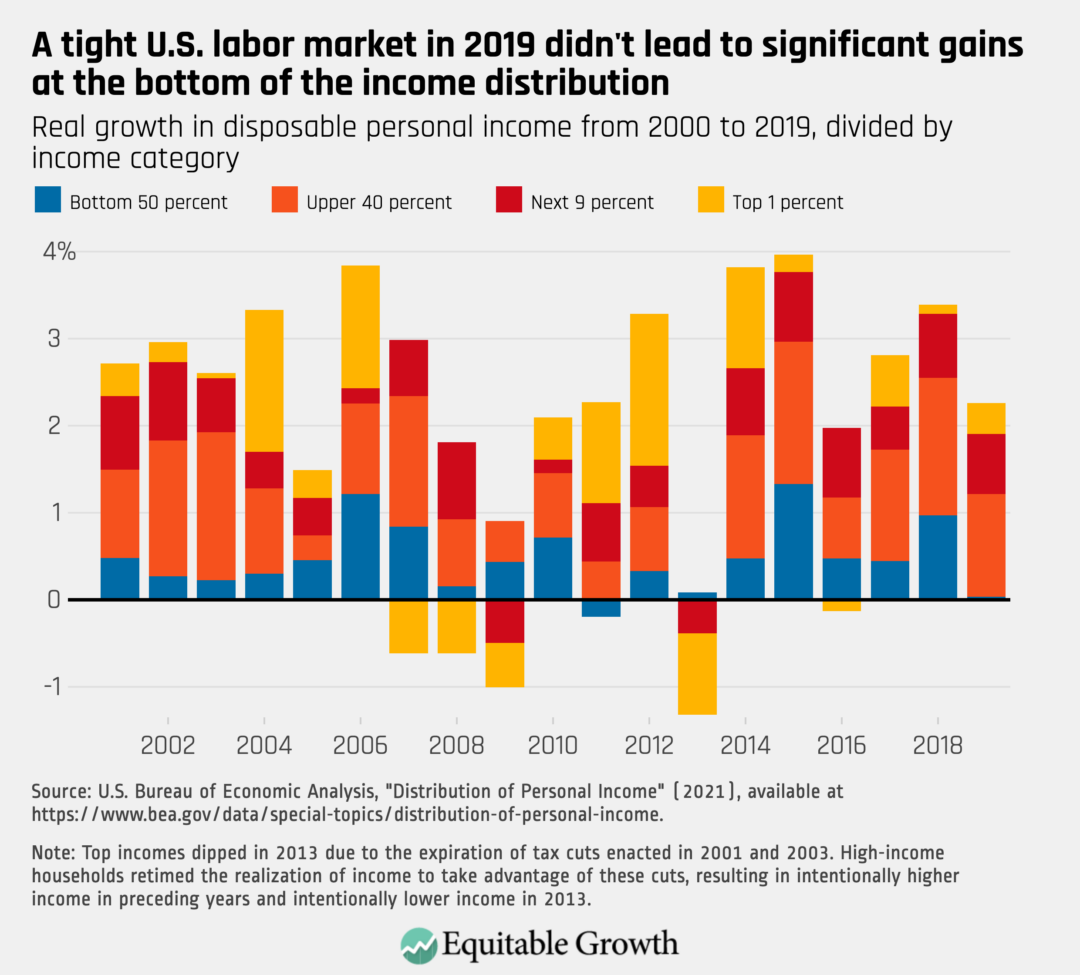

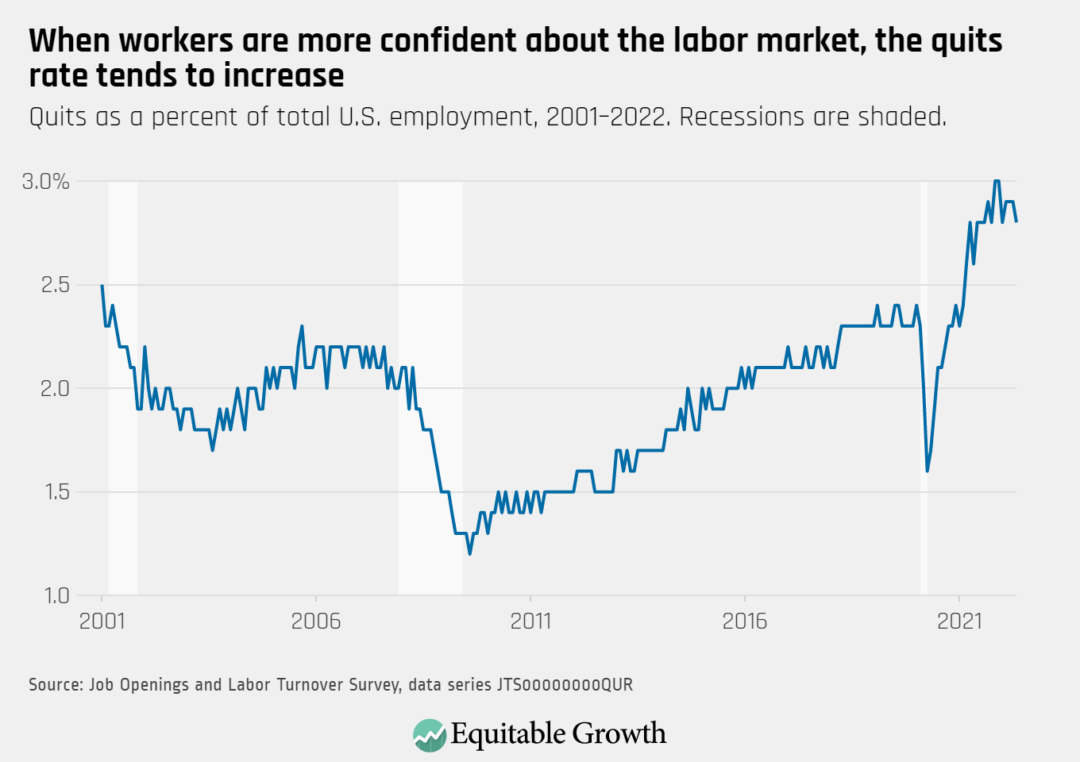

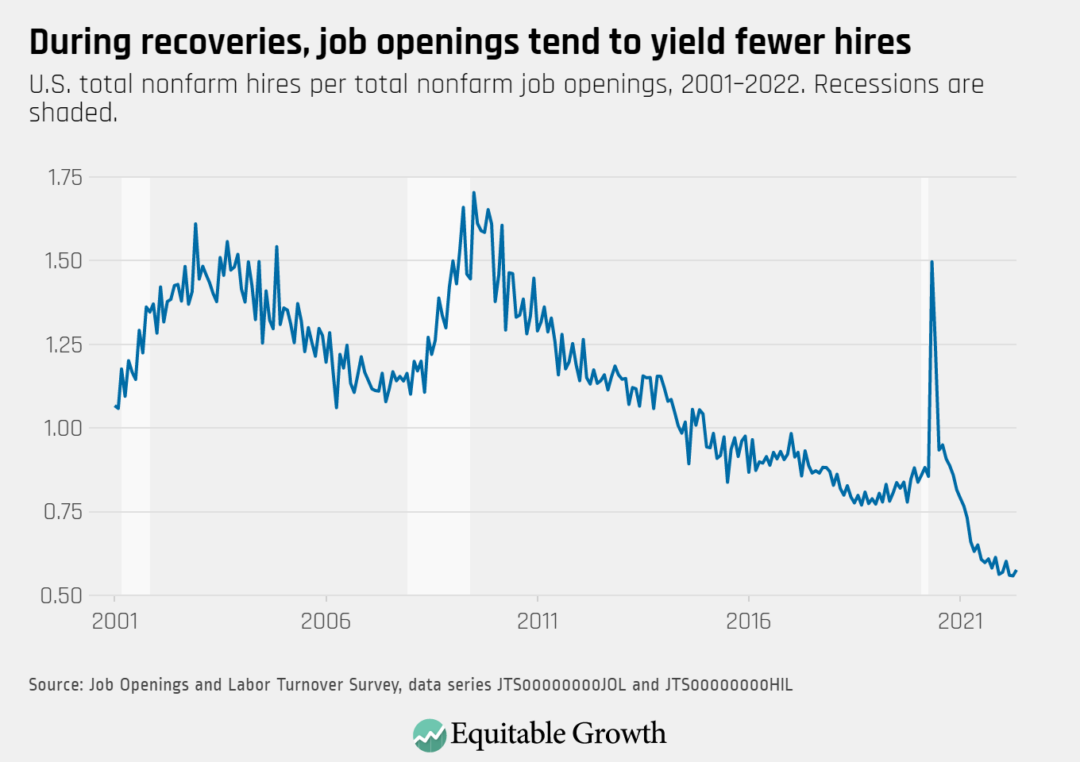

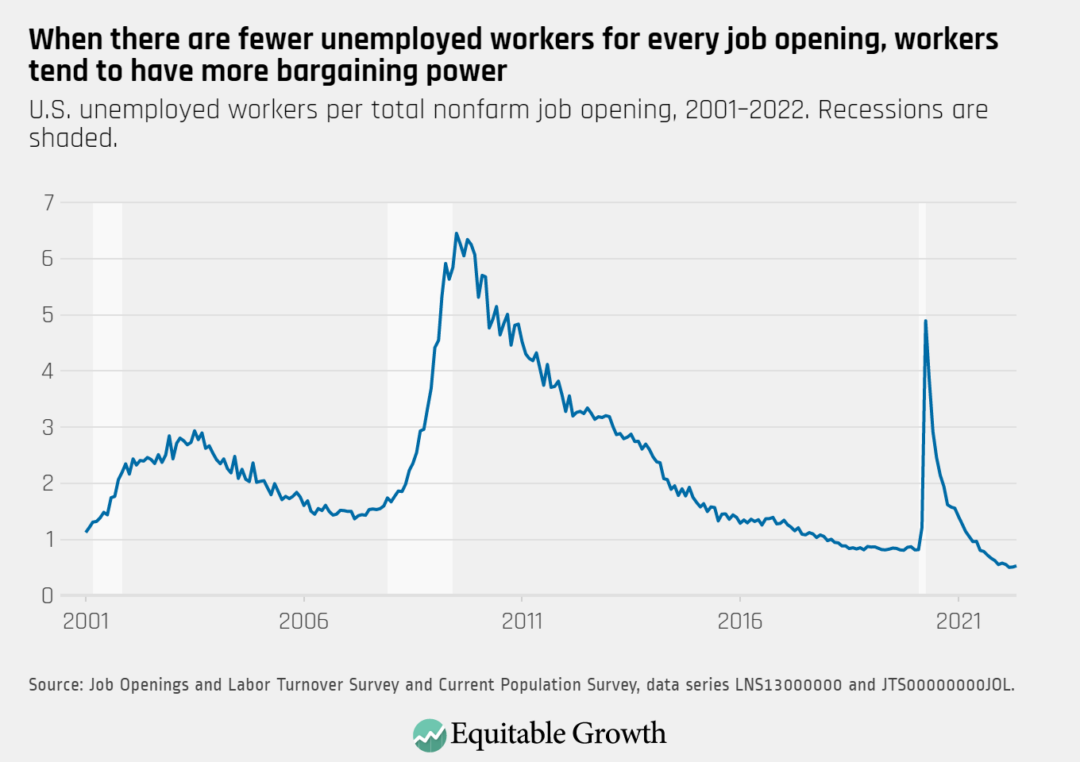

Abstract. This paper constructs high-frequency and timely income distributions for the United States. We develop a methodology to combine the information contained in high-frequency public data sources—including monthly household and employment surveys, quarterly censuses of employment and wages, and monthly and quarterly national accounts statistics—in a unified framework. This allows us to estimate economic growth by income groups, race, and gender consistent with quarterly releases of macroeconomic growth, and to track the distributional impacts of government policies during and in the aftermath of recessions in real time. We test and successfully validate our methodology by implementing it retrospectively back to 1976. Analyzing the COVID-19 pandemic, we find that all income groups recovered their pre-crisis pretax income level within 20 months of the beginning of the recession. Although the recovery was primarily driven by jobs rather than wage growth, wages experienced significant gains at the bottom of the distribution, highlighting the equalizing effects of tight labor markets. After accounting for taxes and cash transfers, real disposable income for the bottom 50 percent of the income distribution was 20 percent higher in 2021 than in 2019 but fell in the first half of 2022, as the expansion of the welfare state during the pandemic was rolled back. All estimates are updated with each quarterly release of the national accounts, within a few hours.

Note: This research was funded in part by Equitable Growth.

“The Welfare Consequences of Regulating Amazon”

Germán Gutiérrez, New York University, Equitable Growth grantee

Abstract. Amazon.com Inc. acts as both a platform operator and seller on its platform, designing rich fee policies and offering some products direct to consumers. This flexibility may improve welfare by increasing fee discrimination and reducing double marginalization but may decrease welfare due to incentives to foreclose rivals and raise their costs. This paper develops and estimates an equilibrium model of Amazon’s retail platform to study these offsetting effects and their implications for regulation. The analysis yields four main results. First, optimal regulation is product- and platform-specific. Interventions that increase welfare in some categories decrease welfare in others. Second, fee instruments are substitutes from the perspective of the platform. Interventions that ban individual instruments may be offset by the endogenous response of existing and potentially new instruments. Third, regulatory interventions have important distributional effects across platform participants. And fourth, consumers value both the Amazon Prime program and product variety. Interventions that eliminate either of the two decrease consumer, as well as total, welfare. By contrast, interventions that preserve Prime and product variety but increase competition—such as increasing competition in fulfillment services—may increase welfare.

Note: This research was funded in part by Equitable Growth.

“‘Compensate the Losers?’ Economy-Policy Preferences and Partisan Realignment in the U.S.”

Ilyana Kuziemko, Princeton University and NBER

Nicolas Longuet Marx, Columbia University

Suresh Naidu, Columbia University and NBER, Equitable Growth grantee

Abstract. Why have less-educated voters abandoned center-left parties in rich democracies in recent decades? While much recent literature highlights the role of cultural issues, we argue that, at least in the United States, the Democratic Party’s evolution on economic issues has played an important role. We show that lower levels of education predict strong support for “predistribution” policies (e.g., guaranteed jobs, public works, a higher minimum wage, protectionism, and support for union organizing) much more than for redistribution policies (taxes and transfers). This robust support for predistribution among the less-educated is mostly unchanged since the 1940s. We then move to the “supply side” of economic policies: Congressional roll-call votes exhibit a decline in predistribution legislation while Democrats are in power, whereas redistribution-related legislation has remained steady. We also document changes in the supply of Democratic politicians. Today, Democratic politicians are far more likely to come from elite educational backgrounds than Republicans, whereas the reverse was true before the 1990s, which might help explain why they no longer propose the predistribution policies favored by the less-educated. We then examine the intersection of the demand and supply sides of economic policy by showing that today, the less-educated are more likely than others to say that Republicans are the party that will keep the country prosperous, whereas from 1948 until the 1990s, the reverse pattern held.

“Monetary Policy and the Labor Market: A Quasi-Experiment in Sweden”

John Coglianese, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Equitable Growth grantee

Maria Olsson, BI Norwegian Business School

Christina Patterson, University of Chicago and NBER, Equitable Growth grantee and former Dissertation Scholar

Abstract. We analyze a quasi-experiment of monetary policy and the labor market in Sweden during 2010–2011, where the central bank raised the interest rate substantially while the economy was still recovering from the Great Recession. We argue that this tightening was a large, credible, and unexpected deviation from the central bank’s historical policy rule. Using this shock and administrative unemployment and earnings records, we quantify the overall effect on the labor market, examine which workers and firms are most affected, and explore what these patterns imply for how monetary policy affects the labor market. We show that this shock increased unemployment broadly, but the increase in unemployment varied somewhat across different types of workers, with low-tenure workers in particular being highly affected, and less across different types of firms. Moreover, we find that the structure of the labor market amplified the effects of monetary policy, as workers in sectors with more rigid wage contracts saw larger increases in unemployment. These patterns support models in which monetary policy leads to general equilibrium changes in labor income, mediated through the institutions of the labor market.

“An Equilibrium Analysis of the Effects of Neighborhood-based Interventions on Children”

Diego Daruich, University of Southern California

Eric Chyn, Dartmouth College and NBER, Equitable Growth grantee

Abstract. To study the effects of neighborhood and place-based interventions, this paper incorporates neighborhood effects into a general equilibrium, or GE, heterogeneous-agent overlapping-generations model with endogenous location choice and child skill development. Importantly, housing costs, as well as neighborhood effects, are endogenously determined in equilibrium. Having calibrated the model based on U.S. data, we use simulations to show that predictions from the model match reduced form evidence from experimental and quasi-experimental studies of housing mobility and urban development programs. After this validation exercise, we study the long-run and large-scale impacts of vouchers and place-based subsidies. Both policies result in welfare gains by reducing inequality and generating improvements in average skills and productivity, all of which offset higher levels of taxes and other GE effects. We find that a voucher program generates larger long-run welfare gains relative to place-based policies. Our analysis of transition dynamics, however, suggests there may be more political support for place-based policies.

“Technology-Skill Complementarity and Labor Displacement: Evidence from Linking Two Centuries of Patents with Occupations”

Leonid Kogan, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and NBER

Dimitris Papanikolaou, Northwestern University and NBER

Lawrence Schmidt, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Bryan Seegmiller, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Equitable Growth grantee

Abstract. We construct new technology indicators using textual analysis of patent documents and occupation task descriptions that span almost two centuries (1850–2010). At the industry level, improvements in technology are associated with higher labor productivity but a decline in the labor share. Exploiting variation in the extent to which certain technologies are related to specific occupations, we show that technological innovation has been largely associated with worse labor market outcomes—wages and employment—for incumbent workers in related occupations using a combination of public-use and confidential administrative data. Panel data on individual worker earnings reveal that less educated, older, and higher-paid workers experience significantly greater declines in average earnings and earnings risk following related technological advances. We reconcile these facts with the standard view of technology-skill complementarity using a model that allows for skill displacement.

“Did Racist Labor Policies Reverse Equality Gains for Everyone?”

Erin L. Wolcott, Middlebury College

Abstract. Labor protection policies in the 1950s and 1960s helped many low- and middle-wage White workers in the United States achieve the American Dream. This coincided with historically low levels of inequality across income deciles. After the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was enacted, many of the policies that had previously helped build the White middle class reversed, especially in states with a larger Black population. Calibrating a labor search model to match unemployment benefits, bargaining power, and minimum wages before and after the Civil Rights Act, I find changing labor policies explain most of the rise in income inequality since the 1960s.

“Oligopsony Power and Factor-Biased Technology Adoption”

Michael Rubens, University of California, Los Angeles

Abstract. I show that buyer power of firms could either increase or decrease their technology adoption, depending on the direction of technical change and on which inputs firms have buyer power over. I illustrate this in an empirical application featuring imperfectly competitive labor markets and a large technology shock: the introduction of mechanical coal cutters in the 19th century Illinois coal mining industry. By estimating an oligopsony model of production and labor supply using rich mine-level data, I find that the returns to cutting machine adoption would have increased by 28 percent when moving from one firm to 10 firms per labor market.

“Industries, Mega Firms, and Increasing Inequality”

John C. Haltiwanger, University of Maryland and NBER

Henry R. Hyatt, U.S. Census Bureau

James Spletzer, U.S. Census Bureau

Abstract. Most of the rise in overall earnings inequality is accounted for by rising between-industry dispersion from about 10 percent of four-digit North American Industry Classification System, or NAICS, industries. These 30 industries are in the tails of the earnings distribution and are clustered especially in high-paying high-tech and low-paying retail sectors. The remaining 90 percent of industries contribute little to between-industry earnings inequality. The rise of employment in mega firms is concentrated in the 30 industries that dominate rising earnings inequality. Among these industries, earnings differentials for the mega firms relative to small firms decline in the low-paying industries but increase in the high-paying industries. We also find that increased sorting and segregation of workers across firms mainly occurs between industries rather than within industries.