Jobs report: U.S. employment data shows continuing strong job gains, with employment in the warehousing and transportation industry well-above pre-pandemic levels

The U.S. economy experienced another month of strong employment gains between mid-February and mid-March, adding 431,000 new jobs. According to the most recent Employment Situation Summary released this morning by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the overall unemployment rate is now nearly at its pre-pandemic rate of 3.5 percent, falling from 3.8 percent in February to 3.6 percent in March. The share of 25- to 54-year-olds with a job—a statistic known as the “prime-age employment-to-population ratio”—climbed from 79.5 percent to 80 percent, and is now less than a percentage point below its February 2020 level.

These aggregate U.S. labor market statistics reveal that, by some measures, several groups of workers have now fully bounced back from the coronavirus recession in 2020 and are benefiting from a tight labor market. At 5.2 percent, the jobless rate for workers without a high school diploma is well-below its pre-pandemic rate. There also were more than 500,000 more men employed in March 2022 than in February 2020, at the start of the coronavirus-induced recession.

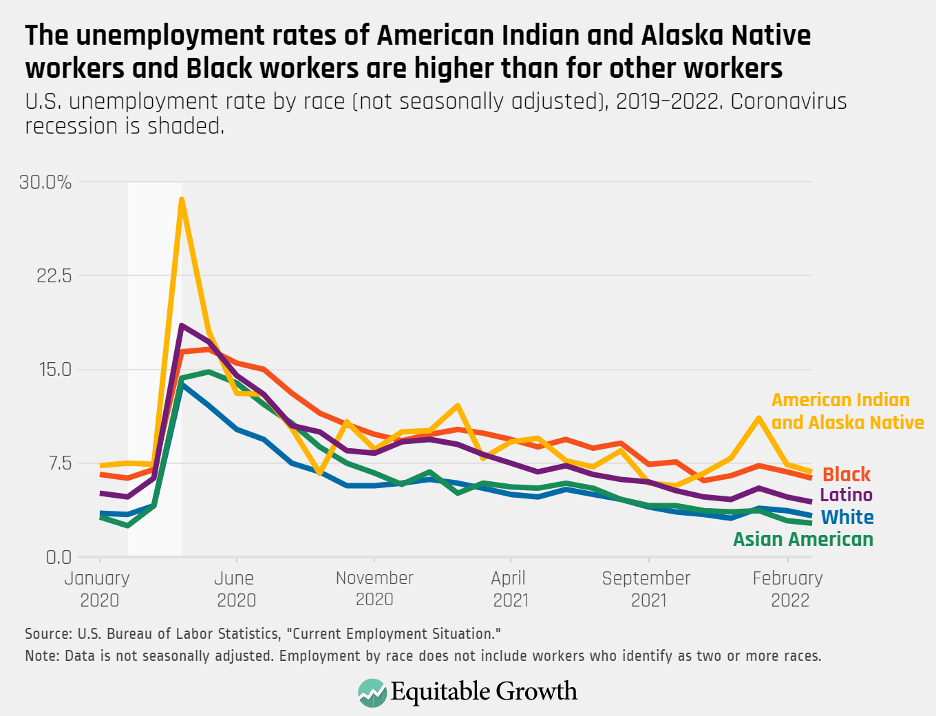

But other workers have yet to recover. With employment still below its pre-pandemic levels, the jobs recovery has been slower for women in general and for Black women in particular. The unadjusted unemployment rate for American Indian and Alaskan Native workers is at 6.8 percent—a statistic we use here because the BLS does not currently publish this group of workers’ jobless rate on a seasonally adjusted basis—while the adjusted rate for Black workers is at 6.3 percent, putting the jobless rates of these groups at about 3.5 percentage points and 3 percentage points above the jobless rate of White workers. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

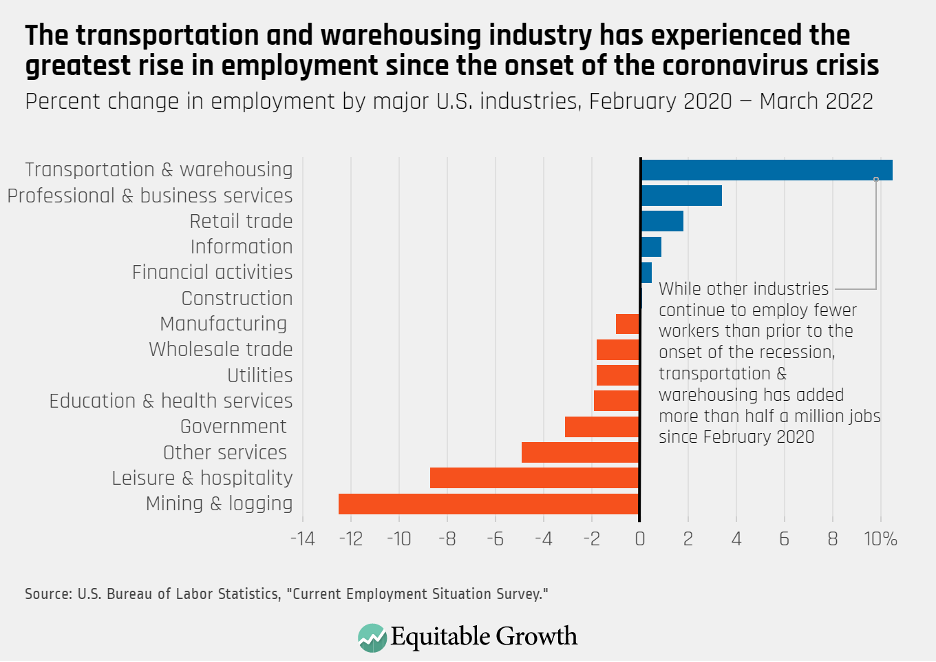

Transportation and warehousing is experiencing the biggest jump in employment

The latest month-over-month job gains were strongest in the leisure and hospitality industry, followed by professional and business services. Over the past two years, however, no sector registered a stronger percentage increase in employment than the transportation and warehousing industry.

While most other major industries continue to employ fewer workers than they did prior to the pandemic, on net the transportation and warehousing sector added more than 600,000 jobs between February 2020 and March 2022. Even though it was not immune to the coronavirus recession’s initial shock to employment, net losses in the sector were relatively small and the bounce-back relatively quick. Indeed, since February 2020 transportation and warehousing industry experienced a 10.5 percent increase in employment. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

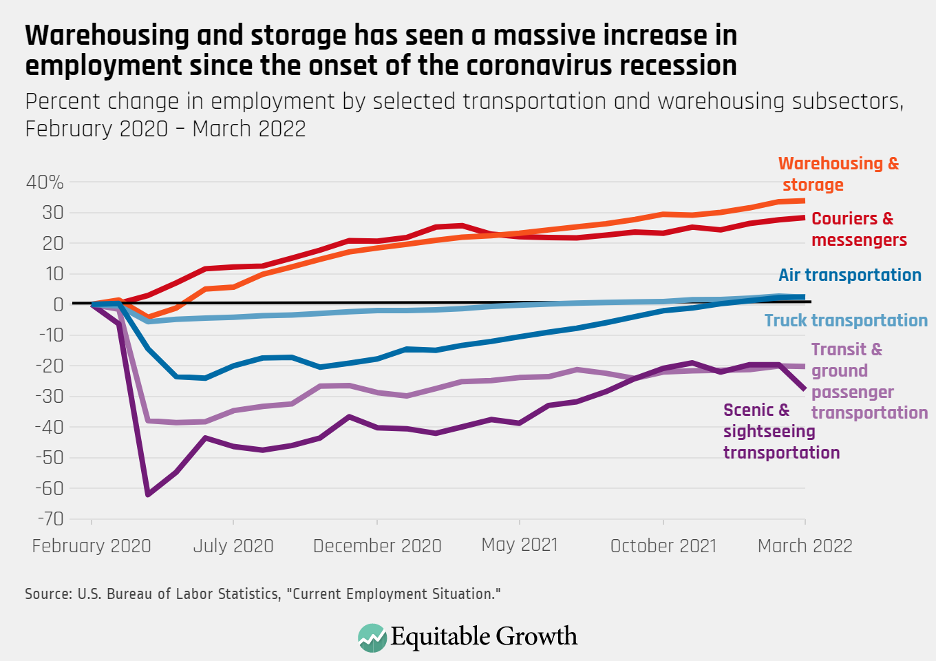

Within this industrial sector, big and somewhat persistent losses in subsectors such as sightseeing transportation and passenger transportation have been more than offset by massive gains for warehousing and storage as well as couriers and messengers. These two subsectors are now at record-high levels of employment. Overall, the transportation and warehousing industry has grown its share of employment over the past two years, going from representing 3.8 percent of the U.S. workforce in February 2020 to representing 4.2 percent in March 2022. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

At least in part, the surge in warehousing and transportation jobs reflects an important pandemic-driven shift in spending. Many consumers stayed home during and after the coronavirus recession and spent more dollars buying goods online. The jump in e-commerce sales for goods such as furniture, electronics, and building materials, in turn, made demand for the services that store, process, ship, and deliver those orders skyrocket.

As a result, throughout the pandemic big employers such as Amazon.com Inc. and Walmart Inc. have hired hundreds of thousands of workers to staff warehouses and distribution centers. And parts of the industry that experienced important disruptions over the past two years, such as commercial airlines, are now expecting this upcoming summer to be the busiest one yet.

Many transportation and warehousing jobs remain poorly paid, unsafe, and precarious

The number of jobs added in the transportation and warehousing sector is a bright spot in the U.S. job market’s recovery, but the industry continues to experience longstanding job-quality concerns that have only become more urgent as pressures on the sector rise. Average pay in the industry—an industry in which men, Black workers, and Latino workers make up a disproportionately high share of the workforce—is currently at $27.79 an hour, almost $4 below the national average.

A 2020 report by Sam Abbott and Alix Gould-Werth at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth shows that in the case of warehouses, pressure to reduce costs and speed-up delivery time led managers to put in place staffing practices that both put a great strain on workers and are built around a business model that relies on irregular work and low-quality schedules.

Domestic outsourcing—a process by which firms subcontract certain roles so that workers are not direct employees—also increased warehouses’ reliance on temporary workers and third-party logistics companies to manage their workforces, further hurting workers’ earnings and opportunities to move up the career ladder. And invasive surveillance and monitoring mechanisms, such as productivity trackers and automated production quotas, led to high rates of workplace injuries and stress, as well as being associated with high turnover rates.

The coronavirus pandemic exacerbated these tough working conditions. Many warehouse workers faced even more pressure to meet productivity quotas and gained little support from employers in terms of access to paid sick leave and Personal Protective Equipment.

Or take trucking. Drivers often receive low pay, have little access to employer-provided benefits, and work long hours—many of which they are not compensated for. The trucking industry relies heavily on independent contractors, meaning that workers are excluded from many income support programs such as Unemployment Insurance, do not receive employer-provided benefits, and are paid on a per-load basis.

In addition, these employment practices and bad working conditions have ripple effects that have contributed to recent supply chain woes. Steve Viscelli at the University of Pennsylvania argues, for instance, that independent contractor status for port drivers worsen supply-chain bottlenecks. Because drivers are paid by the load rather than by the hour, shipping companies bare no costs when using truckers’ time inefficiently, exacerbating delays when unloading cargo.

Job growth needs to be matched by better job quality for the economic recovery to be sustainable and equitable

As one of the fastest growing industries in the U.S. economy, ensuring economic security and good job-quality for warehousing and transportation workers is essential to achieve broad-based growth and supply-chain resilience. An important first step would be to rein back the misclassification of workers as independent contractors—a practice that is especially pervasive in parts of the industry such as trucking and ground delivery. This misclassification hurts the earnings and economic security of middle- and low-wage workers, and deprives workers of labor rights and protections they are entitled to by law.

Policymakers also need to update laws, regulations, and enforcement approaches to address the ways employers are using technology in these sectors, including workplace monitoring technologies and algorithmic management. One example is a new law that went into effect in California earlier this year requiring that employers’ warehouse production targets or quotas are transparent and don’t prevent workers from taking required breaks.

Yet without adequate enforcement resources, such laws rely on worker complaints for enforcement, which research shows may be least effective for most vulnerable workers. In building these resources, policymakers at both the federal level and in states and localities can support strategic and co-enforcement approaches to strengthen labor standards to protect low-wage workers in high-violation sectors such a transportation and warehousing.

Underlying all of these approaches to boost job quality is the necessity to both raise wage standards and provide institutional support for worker power. Many warehousing and transportation workers want to join or form a union because workers can improve their working conditions and have a say in practices that affect them and their families. This includes the types of policies that strengthen unions and workers’ ability to bargain as well as policies such as just cause job protections that help protect workers from being unfairly fired or retaliated against.