Weak income support infrastructure harms U.S. workers and their families and constrains economic growth

Overview

The coronavirus public health emergency and resulting economic recession brought into stark relief the engrained problems with the system of income support for U.S. workers and their families. People in the United States access income support from a wide range of programs, including Social Security, Unemployment Insurance, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families program, to name a few.

Despite the number of programs that make up our income support system, many people who need this support are blocked from accessing it. During the COVID-19 crisis, the existing income support infrastructure has been wholly insufficient for providing relief to those who needed it.1 And while the pandemic-specific income supports delivered through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act and related programs successfully blunted some of the worst pain of the pandemic, they also failed to deliver for all who needed income support due to sustained underinvestment in these key income support programs over the past half-century.2

The coronavirus health and economic crisis is being felt widely by millions of U.S. workers and their families, yet people across the country face crises of their own every day no matter the broader economic or public health outlook. Whether it’s a personal or national crisis, the inability to access income support programs to weather unexpected storms has serious consequences, especially for many workers of color, women, and their families. Indeed, the coronavirus recession exposed already deep inequalities in access to income supports along lines of race and gender.3

What is it, precisely, that stops people from accessing income supports? There are three main barriers:

- Eligibility rules are too strict.

- Benefits are too hard to access even when people are eligible.

- Benefits amounts are too low.

No matter one’s place in the income distribution at any given time, these weaknesses in our nation’s income support system prevent the U.S. economy from reaching its full potential through lowered labor force participation, a weakened macroeconomy during economic recessions, and underinvestment in the human capital of the next generation of workers. What’s more, all of us are likely to face a personal need for income support at some point over the course of our lives.

So, let’s examine the challenges confronting the United States’ system of income supports. Then, we will turn to examining why these are problems both for our economy at large and ourselves as individuals.

Problems with our current system of income support

We define income supports as those programs that transfer cash to households (including both social insurance programs that make transfers based on past earnings among other criteria, social welfare programs that make transfers based on current income and wealth levels among other criteria, as well as income transfers made through the tax system) and in-kind transfer programs that relieve pressure on household budgets and effectively provide income support (for example, when households receive food or housing support they no longer need to spend their limited income on food and housing and can instead use that cash to cover other needs). Together these distinct types of programs create our nation’s system of income supports. Let’s examine the challenges confronting our income support system across each of the three criteria mentioned before: eligibility, accessibility, and adequacy.

Eligibility rules are too strict

Despite fallacious stereotypes about profligacy in income support programs, it is actually intentionally quite hard to access them in the first place.4 Eligibility criteria typically screen out many people based on their family status, asset levels, age, or ability status. Simply by getting married, maintaining a modest “rainy day” fund, or keeping a reliable car, a person can lose eligibility for an income support program.5

Additionally, to access many income support programs, a person must be employed—despite the fact that lacking income may be the factor that is preventing a person from maintaining employment.6 If a person cannot afford transportation or child care, for example, it can be difficult to stay employed.

Since the 1990s, changes to our income support system have only further tied eligibility to work requirements, with the replacement of Aid to Families with Dependent Children with the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program and the creation of the Earned Income Tax Credit. Even the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, colloquially known as food stamps, has work requirements.7

While many people with inadequate incomes are indeed active participants in the labor force, others may have caretaking obligations, health challenges, or face discouragement in the search for employment situations that are safe.8 When workers hit a moment in their lives when they are unable to be in the labor force, this may actually be the time they need income support the most.

Benefits are too hard to access

But even among people who meet all the eligibility requirements for income support, the rate at which they access those benefits remains low.

The low proportion of eligible people accessing UI benefits provides a salient example of how systems and processes that are out of date or purposefully difficult to navigate keep people from accessing the income support they need and are eligible for.9 In the spring of 2020, an unprecedented number of workers were laid off as a result of the coronavirus recession and applied for Unemployment Insurance. More than 1 in 7 American workers applied for income support through the UI program.10

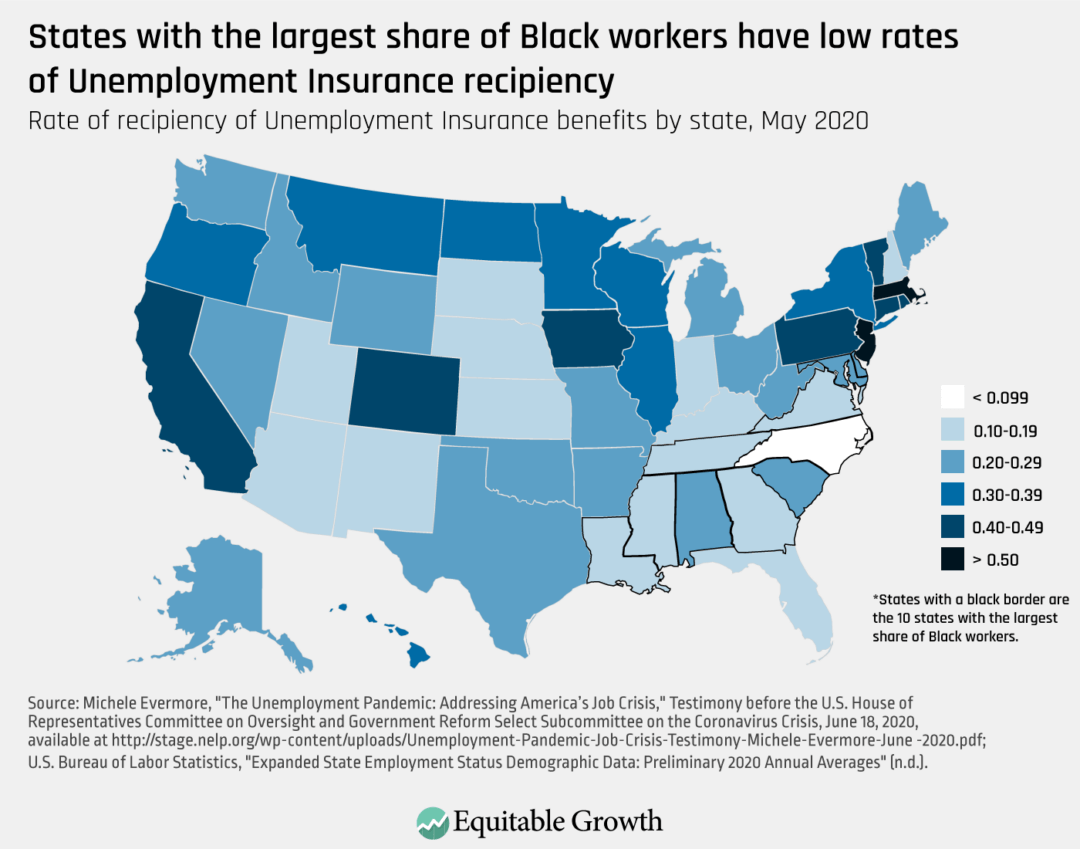

Yet poorly designed systems for applying for benefits, from understaffed phone lines to arcane websites, meant that millions of workers waited weeks to get the payments they were eligible for, if they got them at all. 11States make choices about whether to invest resources in improving system accessibility, and racism appears to shape these choices. Rates of UI access are low in states with a greater share of Black workers.12 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Many headlines highlighted the difficulty faced by workers who lost their jobs through no fault of their own in accessing Unemployment Insurance during the early days of the pandemic, but this is not the only example of the challenges of claiming income support for which one is eligible. In all public health and economic contexts, people struggle to travel to Social Security Administration field offices to complete disability applications, complete the paperwork necessary to recertify for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and correctly document their work participation to remain eligible for the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program.13

The many difficulties people eligible for income support face is a policy choice, not an inevitability of bureaucratic programs.14 There are examples of income support programs with high take-up rates, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and Social Security. The EITC has a nearly 80 percent take-up rate, and 97 percent of elderly Americans receive Social Security benefits.15

A key reason for the high take-up rates for these two income support programs is the lack of red tape. Filing one’s taxes once a year and submitting an initial application are all that is required to receive these sources of income support. In stark contrast to programs with lower take-up rates, such as Unemployment Insurance and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, there is no regular ongoing process that people have to go through to prove their eligibility. Indeed, the relative absence of bureaucratic hurdles associated with claiming tax credits is a factor that influenced Congress’ recent passage of legislation that provides income support to children delivered through through periodic payments of a fully refundable Child Tax Credit during 2021.16

Benefit amounts are too low

Even people who surmount the obstacles of meeting eligibility requirements and navigate the process required to gain access to income support find that the income is insufficient to help meet their basic needs. The maximum monthly amount that a family of four with no income receives from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program is $680, or $5.48 per person per day.17 Families with any income at all receive less than this.

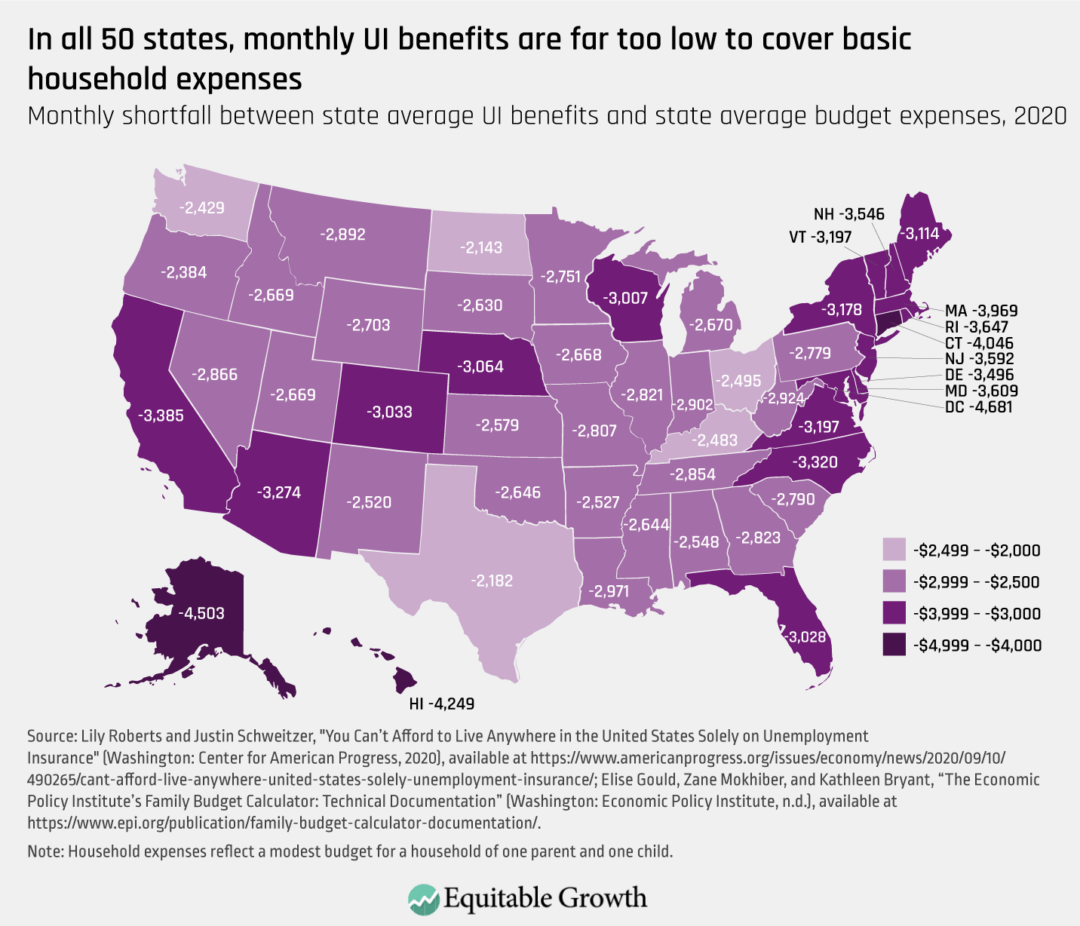

Despite being a social insurance program, Unemployment Insurance also doesn’t begin to provide enough income to make up for the wages lost when a job is lost.18 Indeed, in no state are regular UI benefits sufficient to cover a person’s basic needs of housing, food, child care, transportation, healthcare, taxes, and other necessities such as clothing and school supplies.19 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

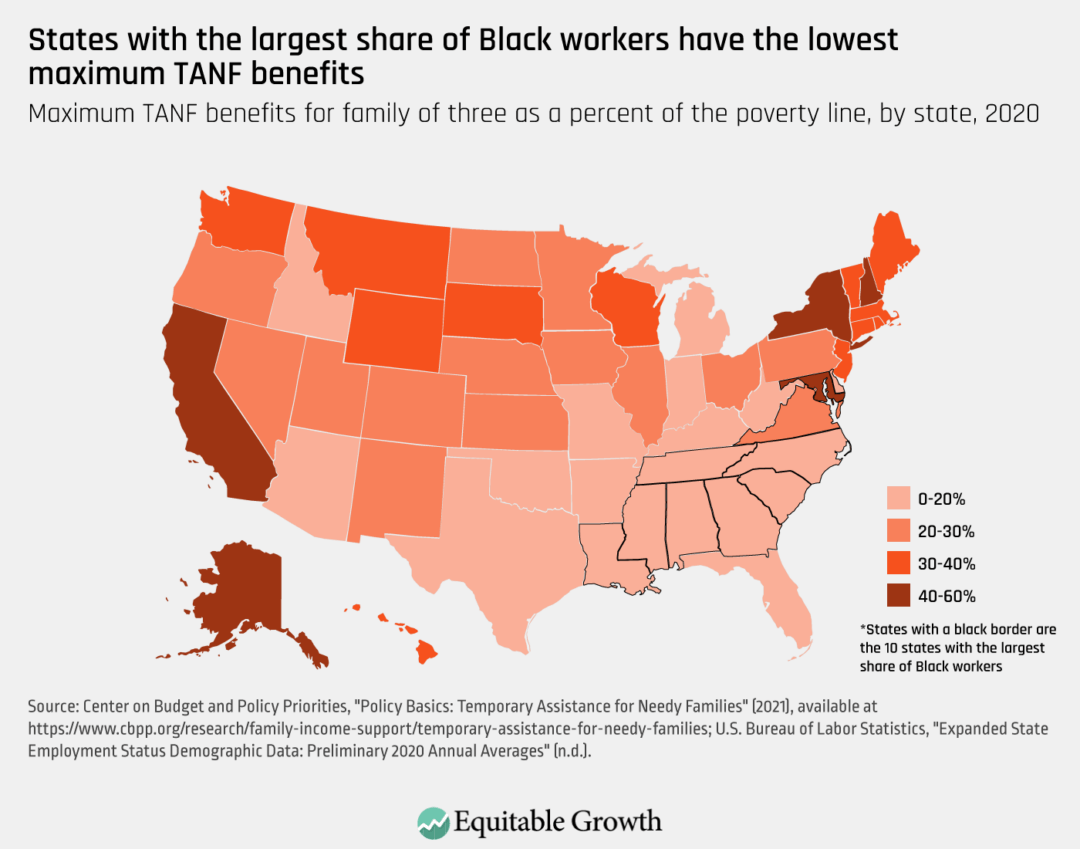

The income support provided by the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families program leaves a family of three below half of the poverty line in almost every state and is time-limited, as its name suggests.20 Racism also shapes the level of support this program provides: States with a greater share of Black residents provide lower levels of income support through the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families program than states with fewer Black residents.21

Figure 3

A weak system of income support harms the entire U.S. economy

A weak system of income support harms individual workers and their families, who, at some point in their lives, experience the vicissitudes of life without adequate income. This weak system also harms the overall strength and growth potential of the U.S. economy.

During recessions, for example, income support acts as an “automatic stabilizer.”22 This means the use of income support programs, such as Unemployment Insurance and SNAP, increases during recessions as workers are laid off and apply for them to help replace their lost incomes.

This kind of income support not only helps those individual workers and their families in need, but also ensures people are still able to purchase goods and services during an economic downturn, which softens the aggregate impact of recessions on the economy.23 Indeed, increased government spending on Unemployment Insurance during the Great Recession of 2007–2009 boosted overall Gross Domestic Product: For every $1 spent on extending UI benefits, we saw an additional $1.61 in economic activity.24

Other income support programs, including the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, could also play this important countercyclical role, but policymakers have so eroded the program’s effectiveness that TANF income support does not respond swiftly when a recession hits.25 When any of these programs are difficult to access or have low benefit amounts, their efficacy as automatic stabilizers is blunted.

Another way a strong income support system strengthens the economy is via its positive impacts on U.S. labor market outcomes. Research shows that access to paid leave, child care support, and EITC income support all increase women’s labor force participation rates.26

Another example comes from the UI system, which research shows improves workers’ “job matching.”27 This means that with more time, people are able to find jobs that are a better match for their skills. This doesn’t just benefit individual workers in terms of higher earnings. Better job matching also benefits the whole economy in the form of increased efficiency, productivity, and higher revenue on those higher earnings.

Weaknesses in our current system of income support also hurt the human capital development of workers, as well as the children of workers.28 This means the economic consequences of a weak system of income support aren’t just felt in the present but also extend into the future. An extensive body of research spanning decades shows the importance of childhood environments for human capital development.29

Human capital plays a crucial role in determining future education and earnings outcomes. Underinvesting in children’s human capital development today means less-educated and lower-earning workers in the future, which depresses the economy’s potential growth.

New research shows how widespread the economic benefits of just a single income support program—specifically, SNAP—can be.30 Hilary Hoynes, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley, and her co-authors find that children with early access to food assistance grew up to be better-educated and have healthier, longer, and more productive lives. This economically benefits all of us in the form of higher tax revenue, lower future expenditures on income support programs, and lower expenditure on the criminal justice system.

Our nation needs a strong system of income support because nearly everyone will need it at some point in their lives

The issues discussed above with eligibility requirements, access difficulty, and income adequacy are all examples of how our current system of income support is failing to meet the needs of so many people in the United States. Such inadequacies are not abstract issues. While a common perception is that only a small proportion of U.S. residents have unmet need for income support, evidence shows that the vast majority of people in the United States are at risk of a change in income that would lead them to experience poverty for 1 to 2 years.31

Nearly everyone at some point in their lives will experience an unmet need for income support. Contrary to racist portrayals of who actually uses and benefits from income support programs, the experience of poverty is actually something that the majority of people in the United States will face in their lifetimes.32

Research by Mark Rank at Washington University in St. Louis and Thomas Hirschl at Cornell University finds that between the ages of 25 and 60, 54 percent of U.S. residents will experience poverty or near poverty at least once.33 Further, 61.8 percent of U.S. residents will spend a year below the 20th percentile of the income distribution, and 42.1 percent will spend a year below the 10th percentile. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Another way to think about this is through the construct of risk. Americans have a 54 percent chance of experiencing poverty at least once during adulthood. This is more than the chance of having appendicitis or getting divorced over the course of a lifetime.34

As economists Jesse Rothstein at UC Berkeley and Sandra Black at Columbia University argue, it is inefficient to have families self-insure against unpredictable risks they cannot reasonably calculate for themselves, such as the chances of losing a job or sufficiently saving for retirement.35 Either way, many families are not in a position to set aside substantial savings in case they experience a dip in income that pushes them under the poverty line.36

Even if families were in such a position, Black and Rothstein explain, “The federal government can provide social insurance protections at a much lower overall cost, and by removing major risks from families’ own balance sheets, enable families to stretch their market earnings further.” This kind of social infrastructure also allows for increased consumption overall.

Because most people will need income support at some point in their lives, and despite all the barriers our current system of income support puts up to accessing support, nearly all people in the United States will access income support programs at some point over the course of their lives. Analysis by the Urban Institute finds that in any given month, nearly 1 in 5 people benefit from SNAP, Supplemental Security Income, TANF, public or subsidized housing, the Women, Infants, and Children, or WIC, program, or the Child Care and Development Fund.37

In addition, analysis by the White House Council of Economic Advisers found that over the 32-year period from 1978 to 2010, more than one-third of all people received support from one of just three of these income supports: the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families and its predecessor programs, or Supplemental Security Income.38 Taking into account additional income support and social infrastructure programs such as school lunches, WIC, or disability insurance, among others, the percentage rises to nearly half of all households. This doesn’t mean that support levels are adequate or that workers and their families will receive income support every time they need it. But it does illustrate the breadth of people that need income support at some point in their lives.

Indeed, the U.S. Treasury Department recently found that when you consider Medicare and Social Security, nearly every single U.S. household receives some form of income support.39 This is an especially important example to keep in mind because, unlike most income support programs, Medicare and Social Security are the two components of our social infrastructure that are easiest to access when needed. Eligibility for Medicare is automatic at age 65 and may not even require a separate enrollment process for people already receiving Social Security.40 Similarly, Social Security’s nearly universal design and eligibility requirements mean that almost every member of the U.S. population will receive its benefits at some point. This makes Social Security the largest anti-poverty program in the United States.41

As the Medicare and Social Security case studies show, it is possible to design an income support system that easily reaches broad swathes of the population. So why do some programs reach so few people? This is an intentional policy choice, informed by our racist history as well as our racist present.42 To prevent Black people in the United States, as well as other people of color, from accessing income support programs we restrict their availability.43 Policymakers make this choice despite the overwhelming evidence that nearly every person in the United States will at some point in time need a strong income support system, regardless of the racial group to which they claim membership.

Conclusion

The U.S. system of income support is inadequate to support U.S. workers and their families. This is an issue because it constrains and limits the overall strength of the U.S. economy, unnecessarily deepening recessions, depressing labor force participation, and harming future growth potential by underinvesting in the human capital of the next generation of workers. The problem is also personal: At some point, everyone will need some form of income support, whether it is to weather a job loss or illness or to be assured of a secure retirement.

By broadening eligibility, increasing the level of income support, and removing barriers to access, policymakers can strengthen these systems of income support in ways that will both help everyone weather the inevitable vicissitudes of life with less undue suffering, as well as strengthen the overall U.S. economy in ways that will pay dividends for all of us.

End Notes

1. Alix Gould-Werth, “The only thing better than strengthening federal social supports now to prevent a coronavirus recession is strengthening them forever” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/the-only-thing-better-than-strengthening-federal-social-supports-now-to-prevent-a-coronavirus-recession-is-strengthening-them-forever/.

2. Zachary Parolin and others, “Monthly Poverty Rates in the United States during the COVID-19 Pandemic” (New York: Center on Poverty & Social Policy, 2020), available at https://www.povertycenter.columbia.edu/news-internal/2020/covid-projecting-monthly-poverty; Amanda Fischer and Alix Gould-Werth, “Broken plumbing: How systems for delivering economic relief in response to the coronavirus recession failed the U.S. economy” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/broken-plumbing-how-systems-for-delivering-economic-relief-in-response-to-the-coronavirus-recession-failed-the-u-s-economy/; Shawn Donnan and Reade Pickert, “U.S. Unemployment Rescue Left at Least 9 Million Without Help,” Bloomberg Businessweek, June 25, 2021, available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2021-06-25/u-s-unemployment-at-least-9-million-americans-didn-t-receive-any-benefits.

3. Time’s Up Foundation, “Foundations for a Just and Inclusive Recovery” (n.d.), available at https://timesupfoundation.org/work/times-up-impact-lab/times-up-measure-up/foundations-for-a-just-and-inclusive-recovery/.

4. Pamela Heard and Donald P. Moynihan, Administrative Burden: Policymaking by Other Means (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2018), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610448789.

5. Richard Balkus and Susan Wilschke, “Treatment of Married Couples in the SSI Program” (Washington: Social Security Administration, 2003), available at https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/issuepapers/ip2003-01.html; Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “A Quick Guide to SNAP Eligibility and Benefits” (2020), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/a-quick-guide-to-snap-eligibility-and-benefits; Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “States’ Vehicle Asset Policies in the Food Stamp Program” (2008), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/states-vehicle-asset-policies-in-the-food-stamp-program.

6. Stacia West and others, “Preliminary Analysis: SEED’s First Year” (Stockton, CA: Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration, 2021), available at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/6039d612b17d055cac14070f/t/6050294a1212aa40fdaf773a/1615866187890/SEED_Preliminary+Analysis-SEEDs+First+Year_Final+Report_Individual+Pages+.pdf.

7. Theodore Figinski, “Issue Brief Four: The Distribution and Evolution of the Social Safety Net and Social Insurance Benefits: 1990 to 2014” (Washington: U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2017), available at https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/economic-policy/Documents/The%20Economic%20Security%20of%20American%20Households-%20the%20Safety%20Net.pdf; Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Policy Basics: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families” (2021), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/temporary-assistance-for-needy-families; U.S. Department of Agriculture, “SNAP Work Requirements” (2019), available at https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/work-requirements.

8. Brynne Keith-Jennings and Raheem Chaudry, “Most Working-Age SNAP Participants Work, But Often in Unstable Jobs” (Washington: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2018), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/most-working-age-snap-participants-work-but-often-in-unstable-jobs.

9. Michelle Evermore, “Are State Unemployment Systems Still Able to Counter Recessions?” (New York: National Employment Law Project, 2019), available at https://www.nelp.org/publication/state-unemployment-systems-still-able-counter-recessions/; Alix Gould-Werth, “Fool Me Once: Investing in Unemployment Insurance systems to avoid the mistakes of the Great Recession during COVID-19” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/fool-me-once-investing-in-unemployment-insurance-systems-to-avoid-the-mistakes-of-the-great-recession-during-covid-19/.

10. Heidi Shierholz, “In the last five weeks, more than 24 million workers applied for unemployment insurance benefits” (Washington: Economic Policy Institute, 2020), available at https://www.epi.org/blog/in-the-last-five-weeks-more-than-24-million-workers-applied-for-unemployment-insurance-benefits/.

11. Gould-Werth, “Fool Me Once: Investing in Unemployment Insurance systems to avoid the mistakes of the Great Recession during COVID-19”; Alyssa Flowers and Heather Long, “Months later, more than 1 million Americans are still waiting for unemployment aid,” The Washington Post, January 4, 2021, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/01/04/unemployment-never-recevied/.

12. Michelle Evermore, “Unemployment Insurance During COVID-19: The CARES Act and the Role of Unemployment Insurance During the Pandemic,” Hearing before the United States Senate Committee on Finance, June 9, 2020, available at https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/09JUN2020EVERMORESTMNT.pdf.

13. Hilary Hoynes and Nicole Maestas, “The Effect of Attorney and Non-Attorney Representation on the Initial Disability Determination Process.” Working Paper (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2016), available at https://www.nber.org/programs-projects/projects-and-centers/retirement-and-disability-research-center/center-papers/drc-nb16-15; Michelle K. Derr and Elizabeth Brown, “Improving Program Engagement of TANF Families: Understanding Participation and Those with Reported Zero Hours of Participation in Work Activities” (Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015), available at https://mathematica.org/publications/improving-program-engagement-of-tanf-families-understanding-participation-and-those-with-reported.

14. Heard and Moynihan, “Administrative Burden: Policymaking by Other Means.”

15. Tax Policy Center, “Tax Policy Center Briefing Book: Key Elements of the U.S. Tax System” (n.d.), available at https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/do-all-people-eligible-eitc-participate; Social Security Administration, “Population Profiles: Never Beneficiaries, Aged 60-89, 2020” (2021), available at https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/population-profiles/never-beneficiaries.html.

16. U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury and IRS Announce Families of Nearly 60 Million Children Receive $15 Billion in First Payments of Expanded and Newly Advanceable Child Tax Credit,” Press release, July 15, 2021, available at https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/Treasury-and-IRS-Announce-Families-of-Nearly-60-Million-Children-Receive-%2415-Billion-Dollars-in-First-Payments-of-Expanded-and-Newly-Advanceable-Child-Tax-Credit.

17. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “A Quick Guide to SNAP Eligibility and Benefits.”

18. Lily Roberts and Justin Schweitzer, “You Can’t Afford to Live Anywhere in the United States Solely on Unemployment Insurance” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2020), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/news/2020/09/10/490265/cant-afford-live-anywhere-united-states-solely-unemployment-insurance/.

19. Roberts and Schweitzer, “You Can’t Afford to Live Anywhere in the United States Solely on Unemployment Insurance.”

20. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Policy Basics: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families” (2021), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/temporary-assistance-for-needy-families.

21. Heather Hahn and others, “Why Does Cash Welfare Depend on Where You Live?” (Washington: Urban Institute, 2017), available at https://www.urban.org/research/publication/why-does-cash-welfare-depend-where-you-live.

22. Alyssa Fisher, “Planning for the next recession by reforming U.S. automatic stabilizers” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2019), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/planning-for-the-next-recession-by-reforming-u-s-macroeconomic-policy-automatic-stabilizers/.

23. Gabriel Chodorow-Reich and John Coglianese, “Unemployment insurance and macroeconomic stabilization” (Washington: The Brookings Institution, 2019), available at https://www.brookings.edu/research/unemployment-insurance-and-macroeconomic-stabilization/.

24. Alan S. Blinder and Mark Zandi, “The Financial Crisis: Lessons for the Next One” (Washington: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2015), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/the-financial-crisis-lessons-for-the-next-one.

25. Marianne Bitler and Hilary Hoynes, “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same? The Safety Net and Poverty in the Great Recession,” Journal of Labor Economics 34 (1) (2016): S403–S444, available at https://gspp.berkeley.edu/assets/uploads/research/pdf/Bitler-Hoynes-JOLE-2016.pdf; Marianne Bitler and Hilary Hoynes, “Strengthening Temporary Assistance for Needy Families” (Washington: The Hamilton Project, 2016), available at https://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/files/bitler_hoynes_strengthening_tanf.pdf.

26. Elisabeth Jacobs, “Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States: A Research Agenda” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2018), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/research-paper/paid-family-and-medical-leave-in-the-united-states/; Taryn W. Morrissey, “Child care and parent labor force participation: a review of the research literature,” Review of Economics of the Household 15 (2017): 1–24, available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11150-016-9331-3; Nada Eissa and Jeffery B. Liebman, “Labor Supply Response to the Earned Income Tax Credit,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 111 (2) (1996): 605–637, available at https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/111/2/605/1938452.

27. Alix Gould-Werth, “The long-run implications of extending unemployment benefits in the United States for workers, firms, and the economy” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/the-long-run-implications-of-extending-unemployment-benefits-in-the-united-states-for-workers-firms-and-the-economy/; Joanna Venator, “Dual-Earner Migration Decisions, Earnings, and Unemployment Insurance” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2021), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/working-papers/dual-earner-migration-decisions-earnings-and-unemployment-insurance/.

28. Naomi Sharp, “Opportunity Costs: Affording the True Costs of College in NYC” (New York: Center for an Urban Future, 2021), available at https://nycfuture.org/research/opportunity-costs-nontuition-barriers.

29. Elisabeth Jacobs and Liz Hipple, “Are today’s inequalities limiting tomorrow’s opportunities?” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2018), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/research-paper/are-todays-inequalities-limiting-tomorrows-opportunities/?longform=true#how_does_economic_inequality_limit_the_development_of_human_potential%3F.

30. Martha Bailey and others, “New working paper shows long-term U.S. economic and health benefits of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/new-working-paper-shows-long-term-u-s-economic-and-health-benefits-of-the-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program/.

31. Mark R. Rank and Thomas A. Hirschl, “Poverty across the Life Cycle: Evidence from the PSID,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 20 (4) (2001): 737–755, available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/pam.1026.

32. Josh Levin, The Queen: The Forgotten Life Behind an American Myth (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 2019), available at https://www.amazon.com/Queen-Forgotten-Life-Behind-American/dp/031651330X.

33. Mark A. Rank and Thomas Hirschl, “The Likelihood of Experiencing Relative Poverty over the Life Course,” PLoS One 10 (7) (2015): 1–11, available at https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0133513.

34. Jane E. Brody, “A Superfluous Organ Can Still Cause Trouble,” The New York Times, November 16, 2004, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2004/11/16/health/a-superfluous-organ-can-still-cause-trouble.html; Rose M. Kreider and Renee Ellis, “Number, Timing, and Duration of Marriages and Divorces: 2009” (Washington: U.S. Census Bureau, 2011), available at https://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/p70-125.pdf.

35. Sandra Black and Jesse Rothstein, “Public investments in social insurance, education, and child care can overcome market failures to promote family and economic well-being” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2021), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/public-investments-in-social-insurance-education-and-child-care-can-overcome-market-failures-to-promote-family-and-economic-well-being/.

36. Federal Reserve Board’s Division of Consumer and Community Affairs, “Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2019 – May 2020” (2020), available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2020-economic-well-being-of-us-households-in-2019-preface.htm.

37. Sarah Minton and Linda Giannarelli, “Five Things You May Not Know about the US Social Safety Net” (Washington: Urban Institute, 2019), available at https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/99674/five_things_you_may_not_know_about_the_us_social_safety_net_1.pdf.

38. Jason Furman, “Chapter 6: The War on Poverty 50 Years Later: A Progress Report” (Washington: White House Council of Economic Advisors, 2014), available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/erp_2014_chapter_6.pdf.

39. Figinski, “Issue Brief Four: The Distribution and Evolution of the Social Safety Net and Social Insurance Benefits: 1990 to 2014.”

40. Social Security Administration, “Medicare Benefits” (n.d.), available at https://www.ssa.gov/benefits/medicare/.

41. Kathleen Romig, “Social Security Lifts More Americans Above Poverty Than Any Other Program” (Washington: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2020), available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/social-security/social-security-lifts-more-americans-above-poverty-than-any-other-program.

42. Ira Katznelson, When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2006), available at https://wwnorton.com/books/9780393328516/about-the-book/product-details; Thomas B. Edsall, “Why Don’t We Always Vote in Our Own Self-Interest?” The New York Times, July 19, 2018, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/19/opinion/voting-welfare-racism-republicans.html; Emily Badger, “The Outsize Hold of the Word ‘Welfare’ on the Public Imagination,” The New York Times, August 6, 2018, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/06/upshot/welfare-and-the-public-imagination.html.

43. Bryce Covert, “The Not-So-Subtle Racism of Trump-Era ‘Welfare Reform’,” The New York Times, May 23, 2018, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/23/opinion/trump-welfare-reform-racism.html.