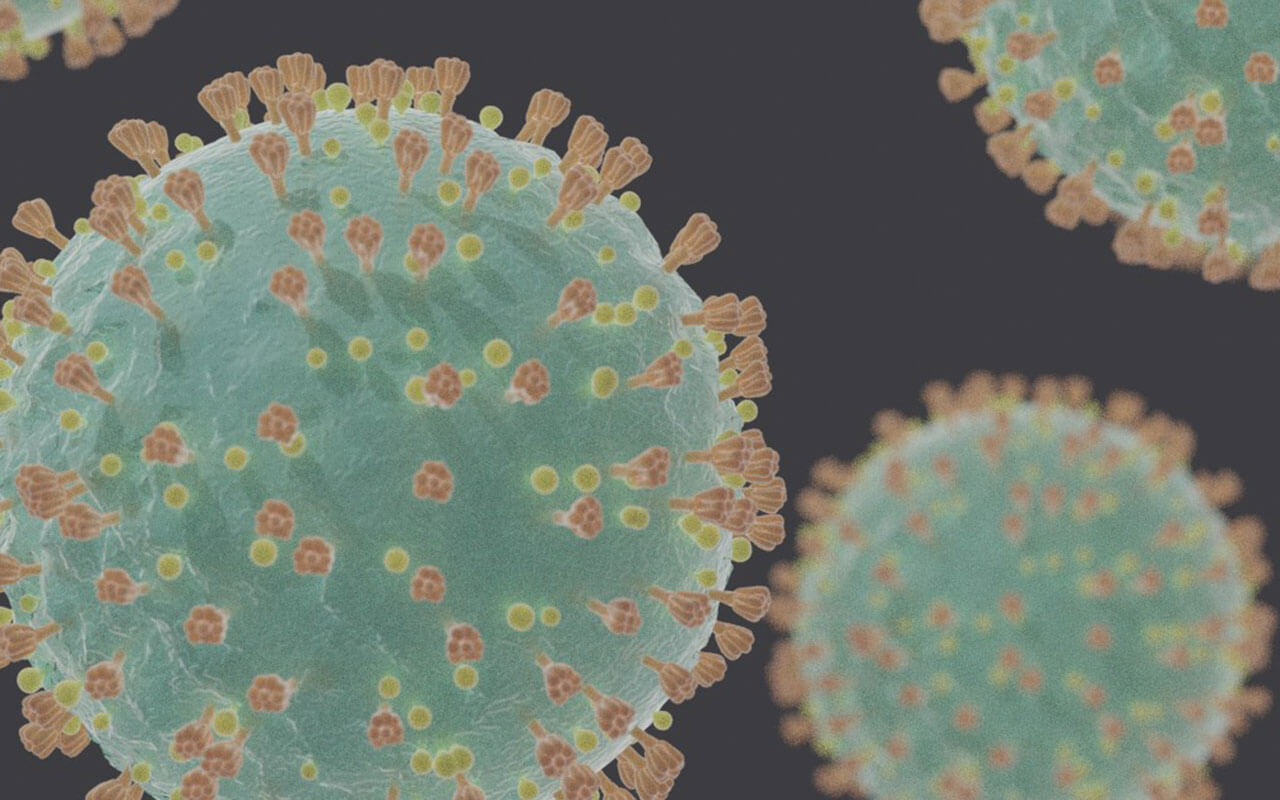

The only thing better than strengthening federal social supports now to prevent a coronavirus recession is strengthening them forever

(This piece has been updated to reflect the passage of revised legislation by the House of Representatives on March 14, 2020. The bill is now under consideration by the Senate.)

The new coronavirus, COVID-19, took the United State by surprise, and leaders across the country are now stepping in to respond. On Saturday, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act

(H.R. 6201)—legislation designed to protect the health, safety, and economic well-being of the populace and to prevent a coronavirus recession. The package includes several key components, including free testing for COVID-19, emergency Unemployment Insurance funding, provisions to make food assistance more accessible to U.S. workers, paid sick time for workers affected by COVID-19, and public health emergency leave so that workers can care for themselves and their families.

Making sure that people affected by the coronavirus outbreak can be tested at minimal cost clearly makes good public health and economic sense. So do the other steps now being proposed in the House legislation. The current crisis also serves as a wake-up call for U.S. policymakers. Boosting unemployment insurance, strengthening food assistance programs, rolling out national policies on paid sick leave, and administering paid leave are all crucial to shoring up our public health system and economic infrastructure for the long term. In addition to the imperative for immediate emergency assistance, making these fixes permanent (and, in many cases, more expansive) would help us be prepared for whatever calamity comes next for the country or for any one of us individually.

Let’s take each program in turn.

Unemployment Insurance

Unemployment Insurance is the major economic program designed to assist workers who lose jobs through no fault of their own and to stabilize the economy in times of macroeconomic downturns. In order to receive partial wage replacement through Unemployment Insurance, a person must have lost a job through no fault of their own and be able to work, available for work, and actively searching for new employment. Unemployment Insurance is a wonderful program, but due to underfinancing and increasing administrative barriers, it is hamstrung in its ability to reach eligible workers. In normal times, this limits Unemployment Insurance’s power to stabilize the U.S. macroeconomy and protect individual well-being. In the context of COVID-19, these problems are compounded by the need for unemployed workers to pound the pavement in search of work or to report to a new job, both of which can pose a public health risk if the job-seeker has symptoms of COVID-19 or is in a high-risk group.

Among other things, the House legislation calls for a needed infusion of resources into the administrative systems of agencies that run Unemployment Insurance programs and in the states that see a 10 percent spike in the unemployment rate. The legislation adapts program features (from work search requirements to experience rating) so that those affected by COVID-19 can access benefits. Getting Unemployment Insurance funds to people who would otherwise be disqualified due to being unavailable for work is key to ensuring that dollars flow into people’s pockets and then into the broader economy.

But unless we make these long-lasting, commonsense reforms to Unemployment Insurance that increase program funding, remove barriers to program access, and improve the already-existing disaster unemployment assistance program, the program will be less effective at helping you or me should we separate from work through no fault of our own or when our country faces the next crisis.

Food assistance

Government programs such as the National School Lunch Program and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, provide low-income children and adults with lunches at school and money they can use to spend on food for themselves and their families. In addition to keeping bellies full and people healthy, SNAP is one of our nation’s most important economic security programs and is crucial to macroeconomic stability. What’s more, undernutrition can harm our immune systems, which defend against COVID-19, along with other illnesses.

As is the case with Unemployment Insurance, recently introduced and strengthened administrative barriers harm people’s ability to access SNAP. In particular, work requirements are hurdles that prevent vulnerable people from accessing these programs: Many low-wage workers struggle to provide documentation of their frequently fluctuating work hours and changing employment status. This, in turn, depresses take-up rates, making the program less effective at buttressing the economy from economic shocks like the one that could be caused by COVID-19.

The House legislation clears a path for children who participate in the School Lunch Program to continue to receive food when schools are closed and allows states to request waivers that will allow them to provide emergency SNAP benefits. It also waives SNAP work requirements that create a barrier between people in economic need and the food assistance that would help them and the economy broadly. Waiving work requirements is smart policy for individuals in need of food and for us as a nation—injecting money into the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program is one of the best ways to ensure that dollars recirculate in the economy. A 2019 study by the U.S. Department of Agriculture examining the program during the Great Recession of 2007–2009 finds a large multiplier effect. Because people who need supplemental nutrition assistance spend that money quickly on the food they need, $1 billion spent on the program generates $1.5 billion of Gross Domestic Product and 13,560 new jobs.

To strengthen SNAP so that it will protect you and me should a personal economic shock hit and protect our country in the case of another crisis, these additional changes should not be a one-time fix. This is one of the best vehicles we have for supporting low-income families and stabilizing the macroeconomy.

Emergency paid sick days

The House legislation requires firms with fewer than 500 employees to provide their workers with 10 emergency paid sick days for health needs related to COVID-19. This policy follows a slew of states and municipalities who have implemented paid sick days and found positive results for workers and for public health. By allowing workers to earn time off to attend to their own medical needs or those of a family member for a small number of days, people can address short-term medical needs without jeopardizing their financial security. This is critical and commonsense policy, necessary to stop the spread of COVID-19 and allow sick individuals to care for themselves.

This policy is an important first step, but by limiting sick time to only needs related to COVID-19, it makes enforcing the policy even more challenging than non-emergency paid sick policies. A requirement that employers allow earned sick leave only works if employers follow it, and—out of ignorance or willful disregard—many employers do not comply with laws on the books. And in a context where diagnostic tests are hard to come by and in which employers can legally deny paid time off to sick workers who may not have COVID-19, it is likely to be difficult to ensure that infected workers receive the paid leave to which they are entitled. Enforceable laws and robust enforcement strategy are necessary to make sure that employer mandates for paid sick days reach all workers, including the most vulnerable, in all times and especially now.

Finally, there is the problem of who is covered by this legislation. The bill includes several “carve outs”—groups of workers who are not eligible for paid sick days. Workers at companies that employ more than 500 people are among the carved-out groups. Thus, many vulnerable workers at the frontlines of food and retail service will be unprotected by the law.

Indeed, Equitable Growth grantees Kristen Harknett at the University of California, San Francisco and Daniel Schneider at UC Berkeley estimate that 5 million workers across the 92 largest companies in retail and food service in the United States lack access to paid sick days, including 347,000 at Walmart Inc. alone. This is a public health hazard that should be addressed in future legislation.

Emergency paid leave

Paid sick days are designed to help workers cope with short-term illnesses, such as the common cold or flu. But for people in high-risk groups, COVID-19 can result in prolonged illness. While the words “paid family and medical leave” often conjure the image of leave to care for a new child, paid leave encompasses much more. The eight states and the District of Columbia that have passed paid leave laws cover leave for one’s own serious medical condition, as well as paid leave to care for an ill or injured family member. There is wide variation in leave length, but typical policies allow for 6 weeks to 26 weeks of leave with partial wage replacement to care for oneself or a family member. What’s more, these programs are funded through a social insurance model, which should make benefits more accessible than through an employer mandate.

The House legislation creates a new federal emergency paid leave benefit program for people affected by COVID-19 that provides partial wage replacement for up to three months. If complications for a COVID-19 patient stretch on beyond their allotted number of sick days, it is important for them to be able to access a system designed to support people with serious medical conditions with partial wage replacement and job protection. It is equally important for their caregivers to be able to access paid caregiving leave, so that they can care for their loved ones without spreading the virus. The rise of COVID-19 shines a light on the need for permanent paid caregiving and medical leave enacted at the federal level. People become seriously ill all the time, and they and their caretakers need paid leave. These policies should be expanded so that no worker in the United States is without them.

A note on program financing

In recognition of the unusual economic moment, the House legislation departs from state and local precedent in terms of funding mechanisms for paid sick days and paid medical and caregiving leave. In states and municipalities with paid sick days, employers build the cost into their business models, and states with paid medical and caregiving leave establish social insurance systems to cover the cost of partial wage replacement. The House legislation requires employers to front the cost for both paid sick days and paid leave, and provides quarterly reimbursement to employers for the compensation they provide employees. Even this may not be enough for businesses struggling to make payroll during economic downturn. To keep business doors open in a time of economic crisis, weekly reimbursement is called for.

It is a tragedy that for decades prior to this current COVID-19 crisis and looming coronavirus recession, Congress failed to give workers the right to earn paid sick days and failed to establish a social insurance program providing wage replacement during personal medical leave and caregiving leave. If these systems were already in place, employers would have paid sick days built into their business models and the government would have built the systems necessary to disburse funds to workers taking time off due to COVID-19.

In the absence of this foresight, we are left with a solution that is coming later than ideal and with a sloppy funding mechanism that employers need to administer at a time when their full attention is needed on the question of how to keep their doors open and their employees on payroll. When we return to normal economic times we should implement permanent, sustainable systems for guaranteed paid sick days and paid caregiving and medical leave so we do not find ourselves in this situation again.

Conclusion

The House legislation responding to the public health and economic threat of COVID-19 is a starting place, and a good one. But in order to prevent a coronavirus recession, we need much more. What comes next should be further permanent expansions of social supports so that we are all protected when the next crisis hits.