Brad DeLong: Worthy reads on equitable growth, September–29 October 5, 2020

Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

1. Excellent to see Michael Kades present his antirust point-of-view on video. Policymakers must pursue legislative reform, tougher enforcement, and new regulations—all three are required and are complementary. Watch him testify before Congress: “Proposals to Strengthen the Antitrust Laws and Restore Competition Online.”

2. The recovery trajectory from the Great Recession of 2007-2009 was bad. The recovery from this downturn may well be worse. I am scared, primarily of the coronavirus, but secondarily of a U.S. economy that has already within recent memory failed to achieve a rapid and healthy recovery. Read my “The Limits of American Recovery,” in which I write: “The recovery experienced so far may represent all that the U.S. economy will get for now. Just because the economy has recovered by 60 percent doesn’t mean that it will get all the way back to 100 percent. After all, the current recovery is unfolding in the shadow of the recovery from the 2008 financial crisis and Great Recession, which was also a period of zero-lower-bound interest rates. It is worth remembering that this previous recovery did not feature a recovery in production, which remained as far below its pre-crisis trend as it had been when the unemployment rate was at its peak. As employment recovered slowly after the Great Recession, productivity continued to lag ever-further behind. But, because there was a persistent lag in output, too, this lack of productivity growth allowed for employment eventually to recover.”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

1. Our financial markets are not doing a good job of pricing expected return properly adjusted for risk right now. Read Gerardo Ferrara, Maria Flora, and Roberto Renò, “Market fragility in the pandemic era,” in which they write: “Flash crashes or longer lasting V-shaped events could also affect markets other than Government bonds … [such as] secondary equity issuances, U.S. Treasury and corporate bond issuances … [and] mutual funds [that are] experiencing large redemptions. This post illustrates a new methodology to detect distressed markets.”

2. The externalities are such that I see little danger of unproductively incentivizing people not to return to work as long as the pandemic lasts. And the magnitude of the windfalls is such that it pushes up my view of the desired top rate. Read John Quiggin, “Inequality and the Pandemic, Part 1: Luck,” in which he writes: “At an individual level, lucky or unlucky breaks of various kinds are much more important than many of us like to believe … The pandemic has reinforced this lesson in the most brutal way possible. As is usual, the poorest members of society have been most exposed … But everyone is vulnerable, and it is a matter of chance whether any of us gets infected, and whether the consequences are harmless, severe or fatal. Similarly, exposure to economic damage is largely random … Concerns about the incentive effects of high taxes on those at the top of the income distribution are misplaced.”

New wealth data show that the economic expansion after the Great Recession was a wealthless recovery for many U.S. households

Overview

The Federal Reserve’s 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, or SCF, released last week, shows that the wealth of many U.S. households never recovered from the shock of the Great Recession more than a decade ago. Although mean (average) wealth of all households in 2019 exceeded mean wealth in 2007 by 9 percent, median (midpoint) wealth declined by 19 percent over the same time period. If housing wealth is excluded, the median wealth of all households in 2019 is about equal to median wealth in 2007.

These several data points show that U.S. households barely recovered their levels of nonhousing wealth over the more than 10 years of economic expansion since the Great Recession of 2007–2009, compared to pre-Great Recession levels. And the data show that households are now less likely to have a home to leverage as a financial asset.

Moreover, disaggregating the data by demographic characteristics shows that many of these households fared worse than the average. Whiter, wealthier, and more educated households fared better, although even these struggled to recover their pre-Great Recession levels of wealth, demonstrating just how broadly felt the slow recovery of wealth has been.

That so many of these households would soon enter the coronavirus recession, which began in February 2020, in worse condition than they entered the Great Recession is a dire warning. This current recession is already deeper and families have fewer resources to draw on to protect themselves from its effects. The upshot: Further aid from Congress is critical to avoid repeating the mistakes made as the United States recovered from the Great Recession.

Disaggregating the 2019 SCF data to discover what kinds of households entered the coronavirus recession with the resources to insulate themselves from job losses, furloughs, or ill health caused by COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, would help policymakers understand what kinds of households need help now to weather this economic and public health crisis. Notably, however, sample sizes in the Survey of Consumer Finances are not large enough for Hispanic and Black communities to support the fine levels of disaggregation necessary for policymakers to target aid effectively and efficiently.

Furthermore, sample sizes for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are so small that the Federal Reserve has to withhold these data from public disclosure entirely, grouping them into a catch-all “other” category to protect the privacy of these households. This is why the Fed should consider oversampling these communities.

The analyses below compare 2007 levels of wealth, from before the Great Recession, to 2019 levels of wealth, and represent peak-to-peak comparisons that tell us whether households with particular demographic characteristics are better- or worse-positioned for the current recession than they were in 2007 for the Great Recession. Most graphs in this column include shaded 95 percent confidence intervals to show levels of statistical uncertainty for these calculations.

White households had a stronger recovery of wealth

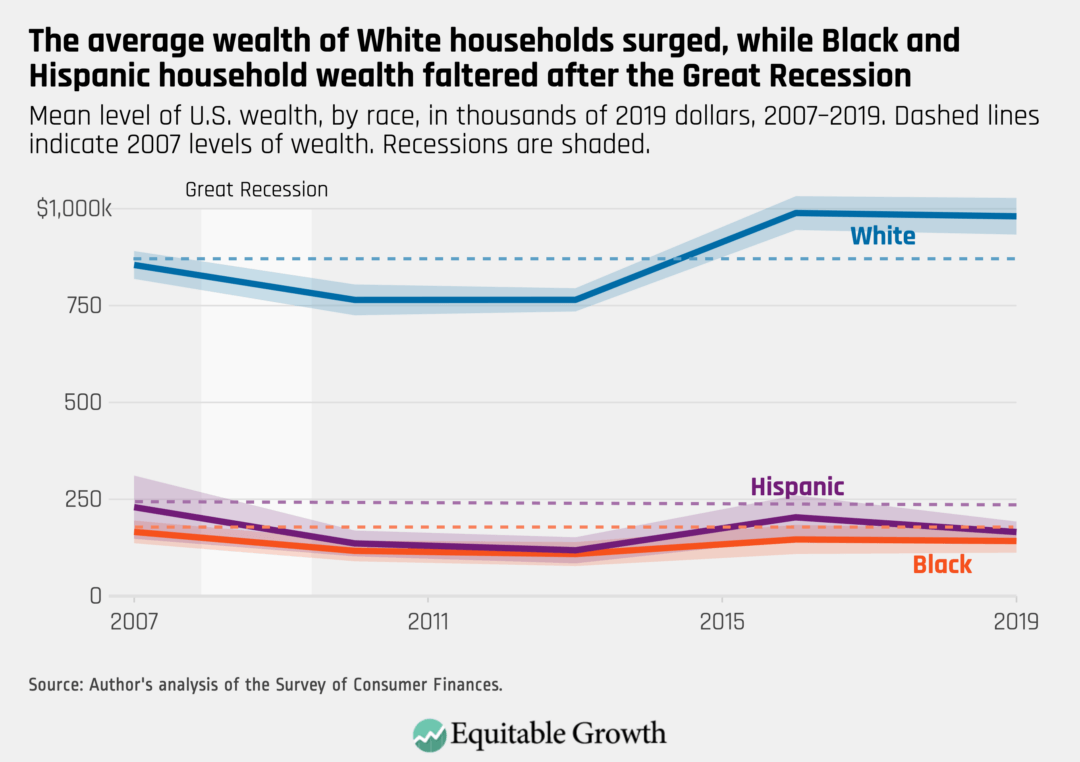

Households that fully recovered their pre-Great Recession levels of wealth are overwhelmingly White. While White households, on average, have 15 percent more wealth in 2019 than in 2007, Black households have 14 percent less wealth, and average wealth for Hispanic households declined by 28 percent. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

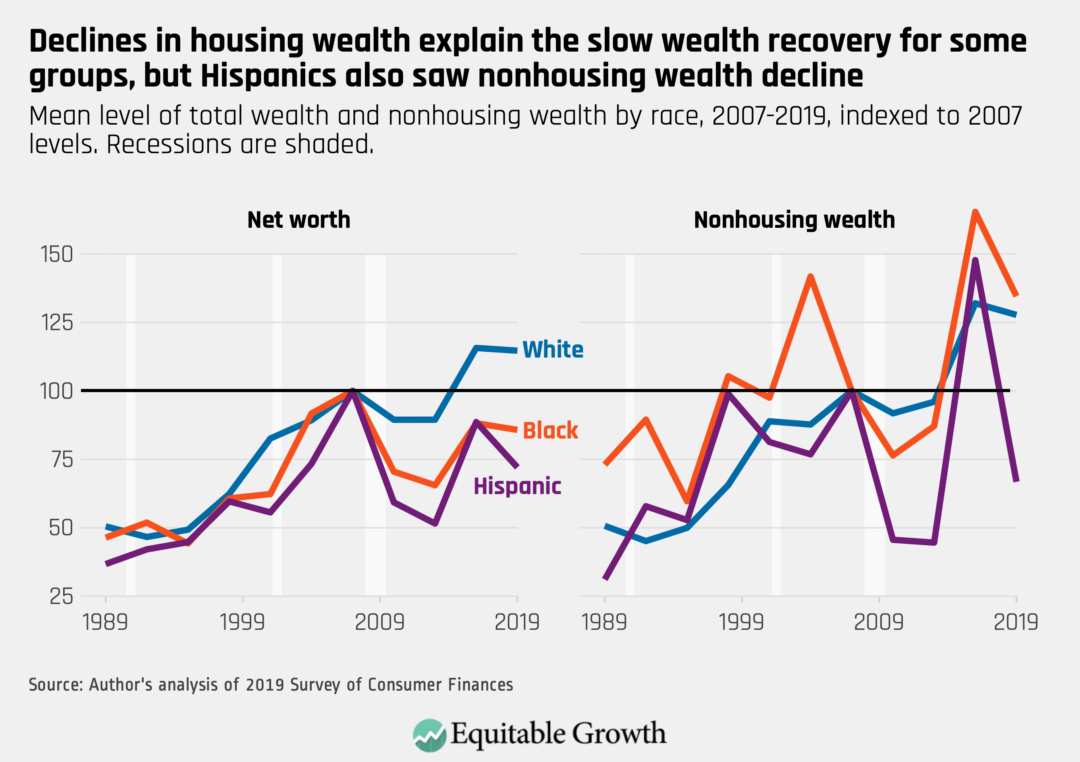

Declines in housing wealth in the United States are responsible for a significant portion of wealth declines since before the Great Recession, but they are not the whole story. The nonhousing wealth of White households between 2007 and 2019 increased by 28 percent after the Great Recession, while it surged 35 percent for Black households and dropped 33 percent for Hispanic households. That average Black wealth declined even though nonhousing wealth surged in the group indicates how important housing wealth is to Black households. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

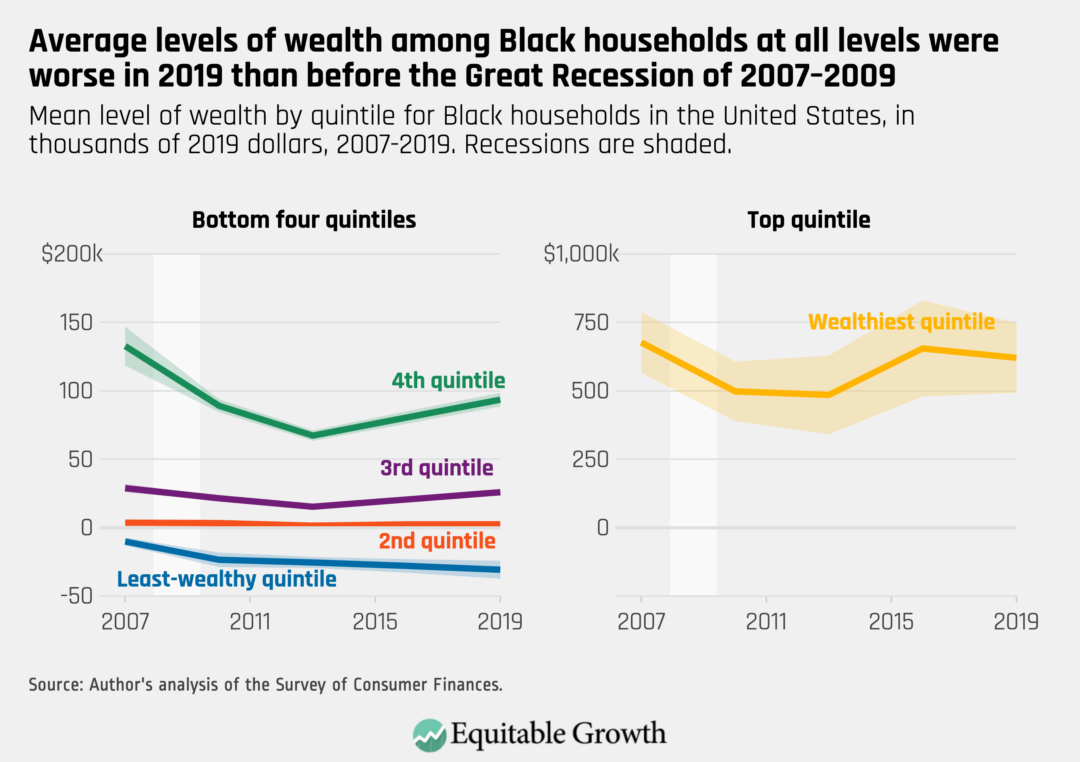

Even high-income Black households did not fully recover what they lost during the Great Recession. Classified by wealth, every quintile of Black households saw declines in their net worth. Middle-quintile Black households saw their net worth decline by 10 percent between 2007 and 2019, for example. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Wealthier households had the strongest recoveries of wealth

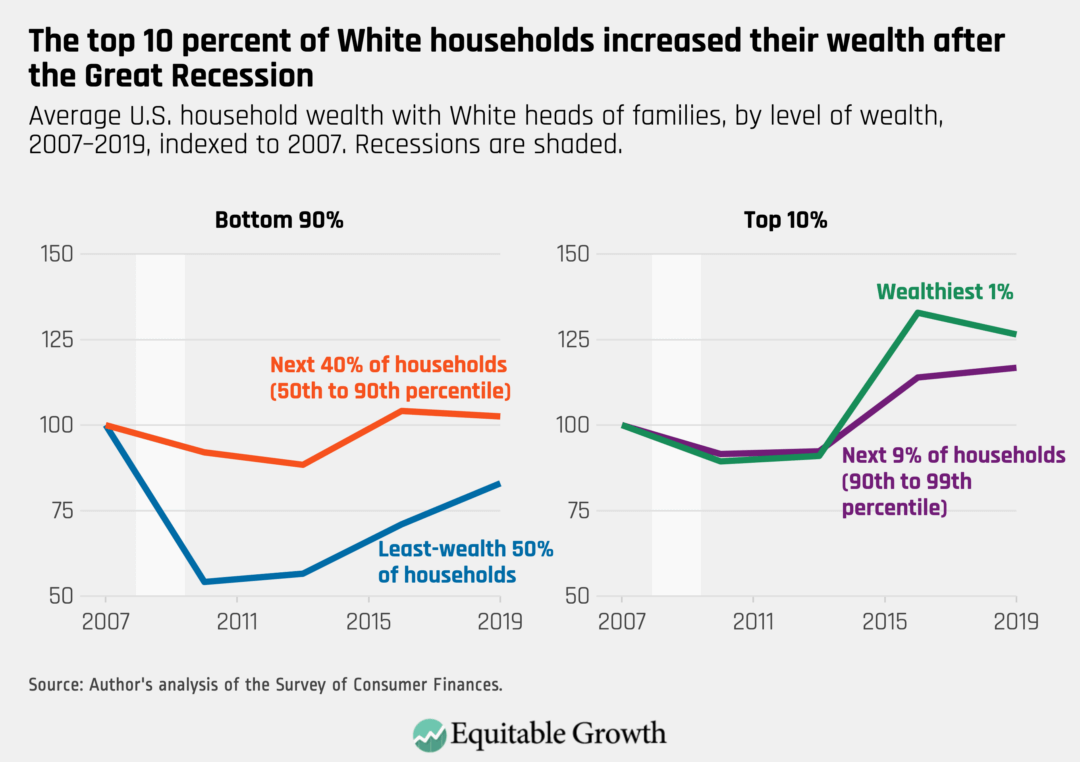

U.S. households headed by White people were more likely to recover or exceed their pre-Great Recession levels of wealth, with much of this growth happening at the top of the wealth distribution. In contrast, households outside the top 10 percent experienced relatively weak recoveries.

In fact, White households in the bottom half of the wealth distribution only recovered about 83 percent of their pre-Great Recession wealth peak. Those in the next 40 percent of the wealth distribution (from the 50th percentile to the 90th percentile) saw very modest gains of about 2.5 percent. Those at the top, however, built a significant amount of wealth. The top 1 percent increased their wealth by 26 percent during the post-Great Recession economic recovery. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

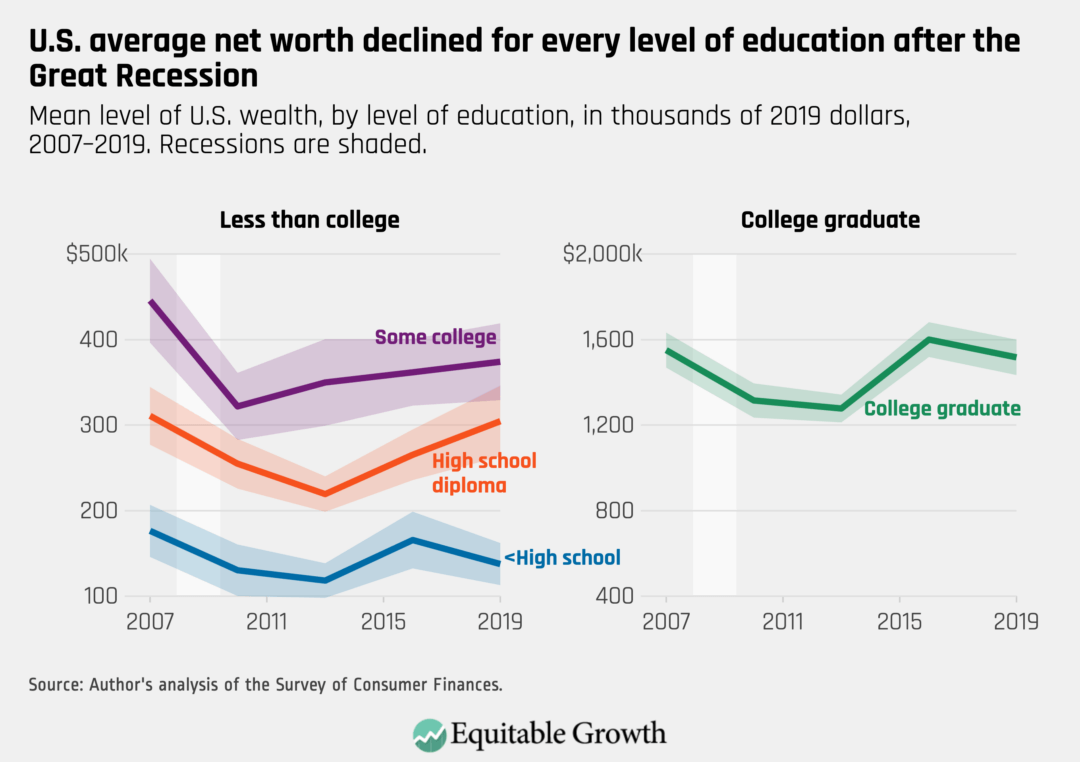

Less-educated households struggled to build wealth in the recovery

Americans grouped by education experienced a similar divide before and after the Great Recession. Those with a bachelor’s degree or more just barely recovered their pre-Great Recession levels of wealth. But Americans in every other educational group saw significant declines in their wealth, although Americans with high school diplomas came closest to recovering. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

This is true even for White households at lower levels of education. Those White households with a head of the family who had less than a high school diploma or with a GED or high school diploma only narrowly recovered their 2007 levels of wealth by 2019. Sample sizes for White households with a head of the family who had some college experience are relatively small, and it is difficult to draw inferences in this group.

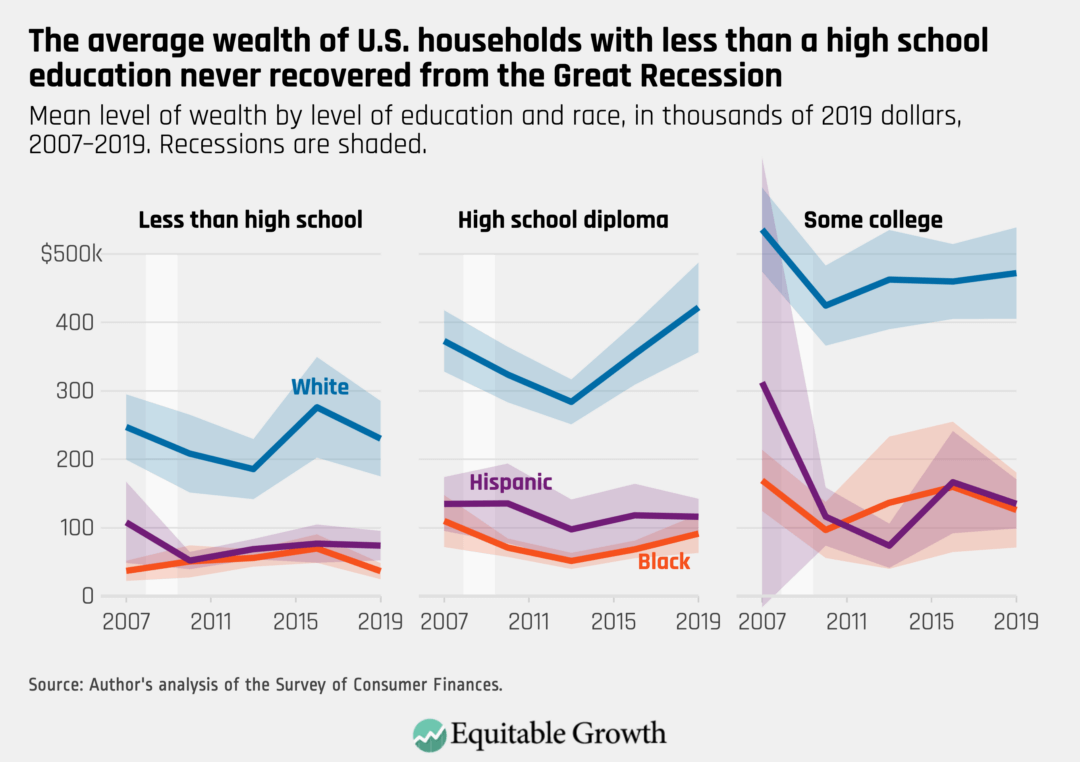

Again, the differences are more stark for households of color. White households with less than a college degree saw their wealth increase by 3 percent between 2007 and 2019. But Black households without a college degree entered 2020 and the coronavirus recession two months later with an average of 17 percent less wealth than what they had in 2007. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

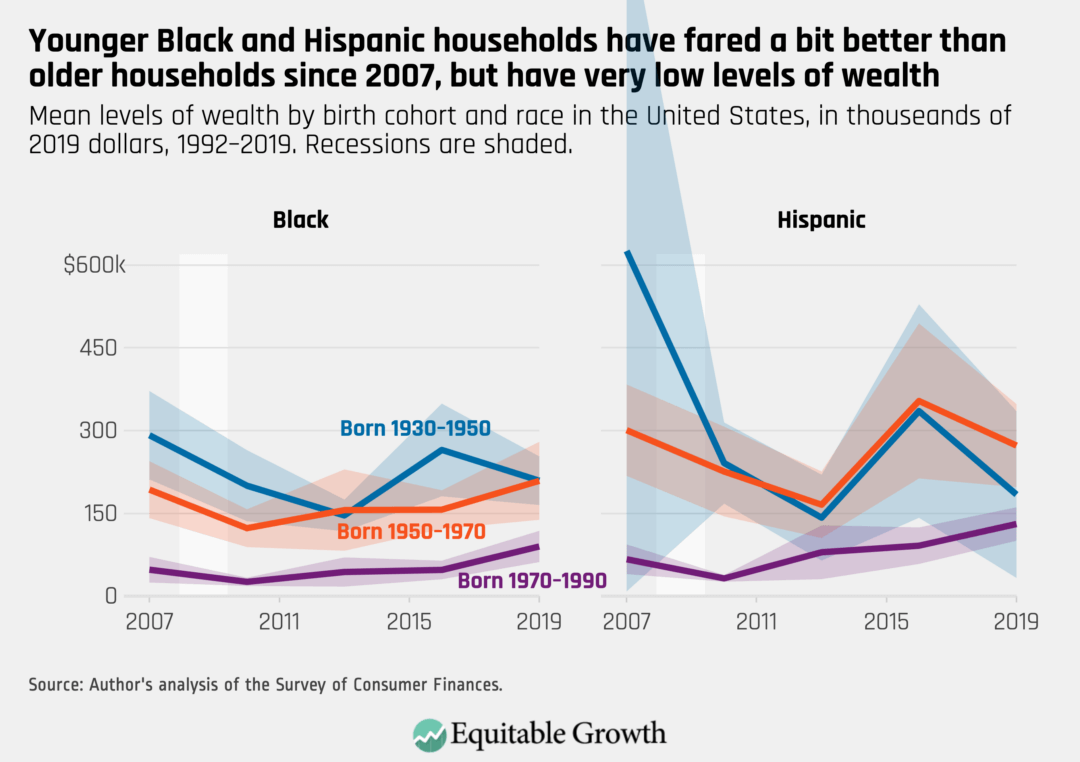

Younger Black households built wealth during the recovery but continue to have very low levels of wealth

From a generational perspective, Black households have levels of wealth far lower than even the youngest White households. A White household where the head of the family was born between 1970 and 1990 had average wealth of about $500,000 in 2019, whereas even the oldest Black households only had average wealth of around $200,000.

Black and Hispanic households of any age had very low levels of wealth entering the Great Recession. But younger generations of both Black and Hispanic households fared better over the course of the recovery after the Great Recession. Black households with heads of families born between 1970 and 1990 increased their wealth by 65 percent between 2007 and 2019, but nonetheless still have very low levels of wealth. (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7

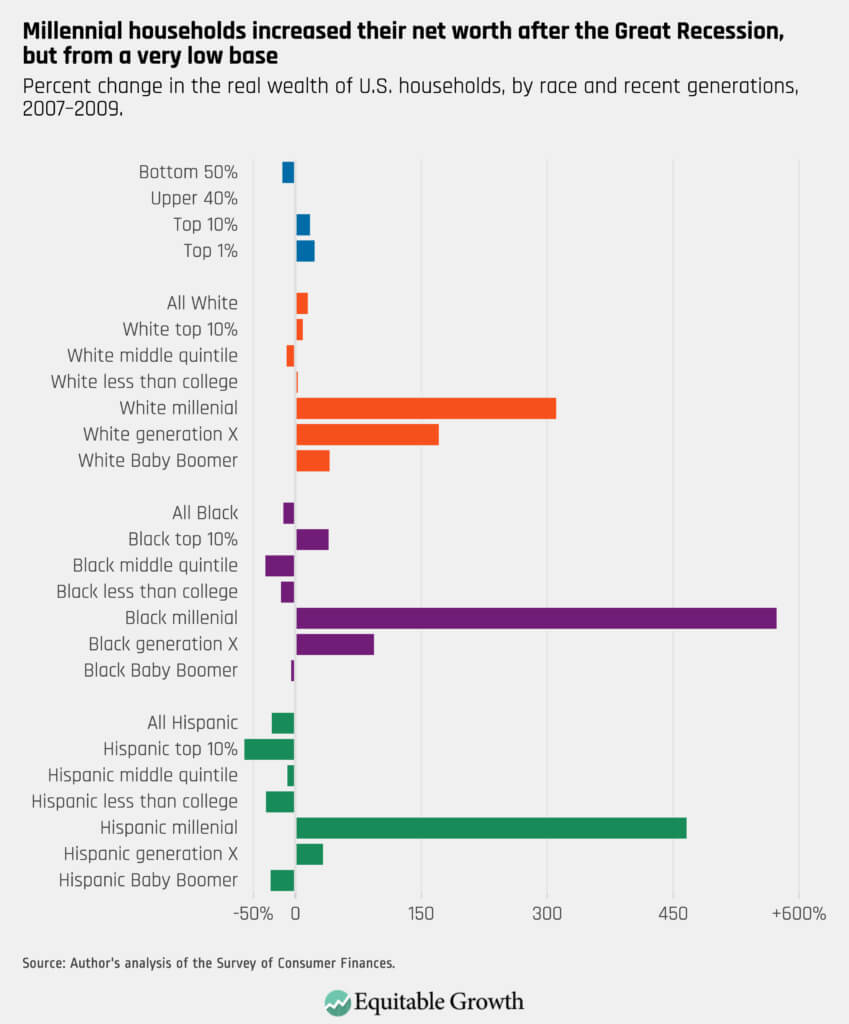

The wealth of many U.S. households is lower entering the coronavirus recession than right before the Great Recession of 2007–2009

Despite the record-long economic expansion of more than 10 years following the Great Recession, many households never fully recovered, pointing to weaknesses in wage growth and in the availability of high-quality jobs that dogged the recovery for nearly its entire length. Notably, millennial households built a considerable amount of wealth during that recovery, but only because they started with very low base levels of wealth, and they had less housing wealth to lose during the Great Recession. (See Figure 8.)

Figure 8

Conclusion

The lessons learned about U.S. household wealth across a variety of measures after the Great Recession demonstrate that the relative paucity of policymaker action after the economic gains from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 fed into the U.S. economy led to an overall weak recovery in U.S. household wealth. Today, that leaves many Americans struggling through the coronavirus recession. And that’s why Congress should not repeat the mistakes made by past Congresses, but rather continue to act forcefully to make sure there is a robust recovery.

Another important takeaway from the data in the Federal Reserve’s 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances is that the huge error bars around Hispanic and, to a lesser extent, Black household estimates of wealth in the graphs above demonstrate how uncertain these estimates become when analyzing the data at the intersection of race and education, age, gender, or other demographics. To support better decomposition of groups, the Federal Reserve should consider instituting oversamples of households of color.

Weekend reading: The most unequal recession in modern U.S. history edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Though recent unemployment data released by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics suggest that overall joblessness is going down, the coronavirus recession is exacerbating long-term trends of decreasing job quality and rising economic vulnerability. These trends are especially harmful to marginalized workers and their families. Unemployment rates for Black, Latinx, Asian American, women, and lower-educated workers are well above those of White men and highly educated peers, and the data indicate that the recovery is and will continue to be uneven among these groups. Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming analyze this month’s Jobs Report and show why the recent data signal an impending disaster for the public sector, particularly in local and state government jobs, which are disproportionately held by workers of color and women. Though job losses so far are not as severe in the public sector as in the private sector, Bahn and Sanchez Cumming explain that government employment was slower to recover in the previous recession and was marked by a shift from decent to low-quality jobs. Another sluggish recovery in the public sector would harm the economic security of these workers, deepen existing labor market disparities, and put a drag on the speedy and equitable recovery our economy desperately needs.

Early in 2018, after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was passed and signed into law by President Donald Trump, the administration began requiring cost-benefit analyses of tax regulations. More than 2 years later, Greg Leiserson writes, it is clear this experiment failed. In a new report and an accompanying blog post, Leiserson details the shortcomings of cost-benefit analyses for TCJA regulations and how the framework for cost-benefit analysis mandated by the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs within the Office of Management and Budget shaped these weaknesses. Namely, the current cost-benefit analysis framework hides revenue-losing, inequality-increasing giveaways by ignoring the revenue and distributional effects of tax regulations. Leiserson explains why a different approach is needed and then provides one, in which the Department of the Treasury leads the process and provides qualitative and, when possible, quantitative evaluations that look at the impacts of tax regulations on revenues, on the level and distribution of the tax burden, and on compliance costs.

Earlier this week, Michael Kades testified before the U.S. House Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law regarding competition in digital markets. His testimony explains the importance of the recent Judiciary Committee investigation into the state of competition in online markets and encourages the committee to continue acting to strengthen the antitrust laws, promote competition online, and protect consumers. Kades runs through various legislative reforms that are needed in addition to enforcement actions, explains why interoperability can work as a mechanism for addressing digital monopoly power, and details other laws and regulations Congress can enact to promote competition.

Catch up on Brad DeLong’s latest Worthy Reads, in which he provides summaries and his takes on recent must-read content from Equitable Growth and other sources. This week, he highlights Heather Boushey’s recent USA Today op-ed on the importance of equitable economic growth especially in the wake of the coronavirus recession, a recent working paper by Michael Kades and Fiona Scott Morton on competition in digital networks, and more.

Links from around the web

While recessions often hit poorer households harder than wealthier ones, the coronavirus recession is undoubtedly the most unequal recession in modern U.S. history. A recent Washington Post analysis from Heather Long, Andrew Van Dam, Alyssa Fowers, and Leslie Shapiro shows how job losses since March have disproportionately fallen on low-wage workers, women, and workers of color. In a series of interactive graphics, the co-authors display the stark disparities in both unemployment and re-employment among various groups within the U.S. labor market. In particular, they write, Black women, Black men, and mothers of school-age children are having the hardest time getting hired back. While those at the top of the income ladder have either faced mild setbacks or none at all, many of those workers lower down on the ladder face what the authors call “a depression-like blow.” The inequality of the economic downturn is a reflection of the outsize impact of the coronavirus public health crisis on communities of color and low-income households.

A recent survey also confirms that Black and Latinx parents are having the most financial difficulty during this recession. Eighty-six percent of Latinx households and 66 percent of Black households reported struggling to afford healthcare, running out of household savings, and having trouble paying bills, compared to 50 percent of White households. Now that many of the government supports enacted earlier this year have expired, writes Giulia McDonnell Nieto del Rio in The New York Times, experts are concerned that the racial divides will continue to grow and exacerbate existing inequalities faced by these communities. This is particularly concerning for households with children, del Rio continues, and indicates that many will experience added long-term financial harm from the pandemic.

Though much of the conversation around the coronavirus pandemic is centered on ending lockdowns and getting people back to work, the reality is that until the public feels safe venturing out of their homes, reopening the economy won’t save small businesses from shuttering. Vox’s Emily Stewart explains why the narrative around reopening only provides false hope for many small businesses around the country, many of which had to close permanently despite implementing additional safety measures. Many people not only are wary of going out in public during a deadly pandemic but also lost their jobs and are not eager to spend money on unnecessary expenses. Simply put, Stewart writes, “you can’t force business as usual when life is not.”

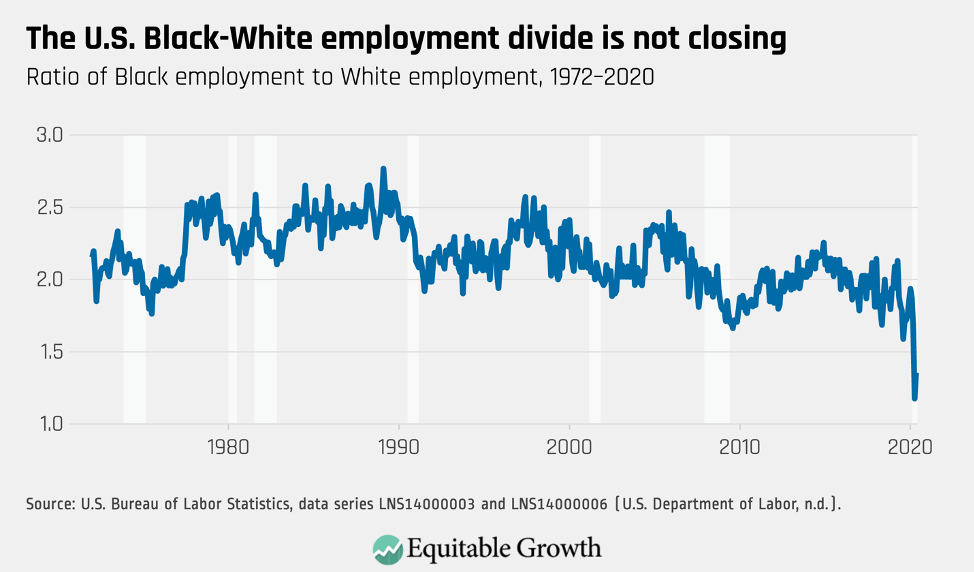

Friday figure

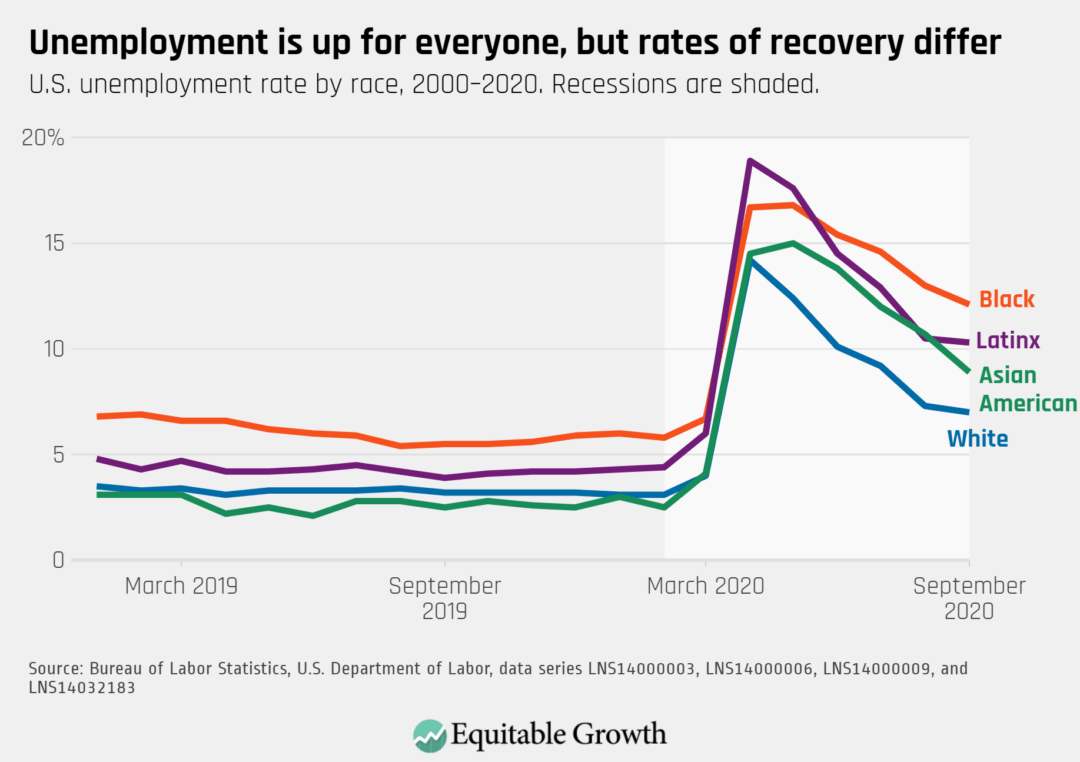

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Equitable Growth’s Jobs Day Graphs: September 2020 Report Edition” by Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming.

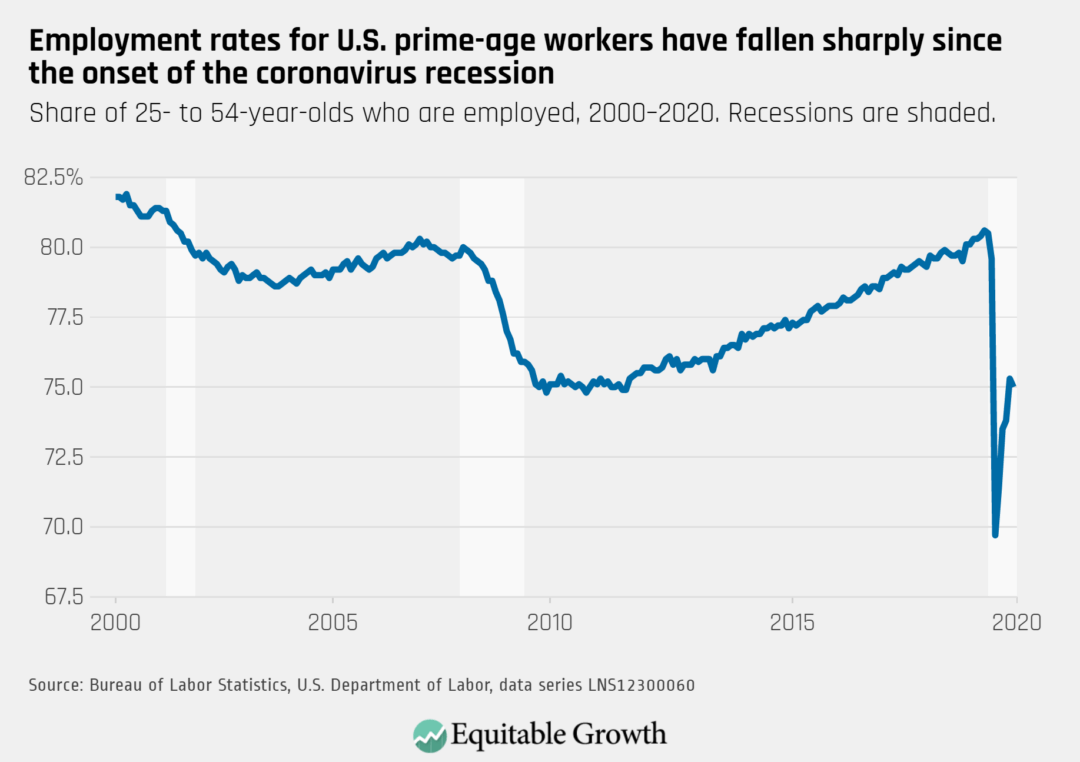

What the coronavirus recession means for U.S. public-sector employment

According to the latest Employment Situation report released by Bureau of Labor Statistics today, the U.S. economy in September added 661,000 nonfarm payroll jobs, reflecting an important slowdown in employment growth. Also known as the Jobs Report, the release shows that the share of 25- to 54-year-old prime-age workers who have a job fell from 75.3 percent in August to 75.0 percent, and the number of unemployed workers who report being on a permanent layoff increased by 345,000 for a total of 3.8 million workers out of 12.6 million unemployed workers in September.

This final Jobs Report before the 2020 presidential election calls into question what policies are needed to foster an equitable and sustained economic recovery in the midst of the coronavirus recession. The report also reflects U.S. labor market conditions more than a month after the expiration of the $600 “plus-up” in unemployment benefits funded through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act. The end of this plus-up is forcing workers to return to work during an uncontrolled pandemic with few other options to support themselves and their families.

As such, there continue to be important income, race, and gender disparities evident in the latest Jobs Report, as well as questions about the quality of jobs being added that underlie last month’s net job gains.

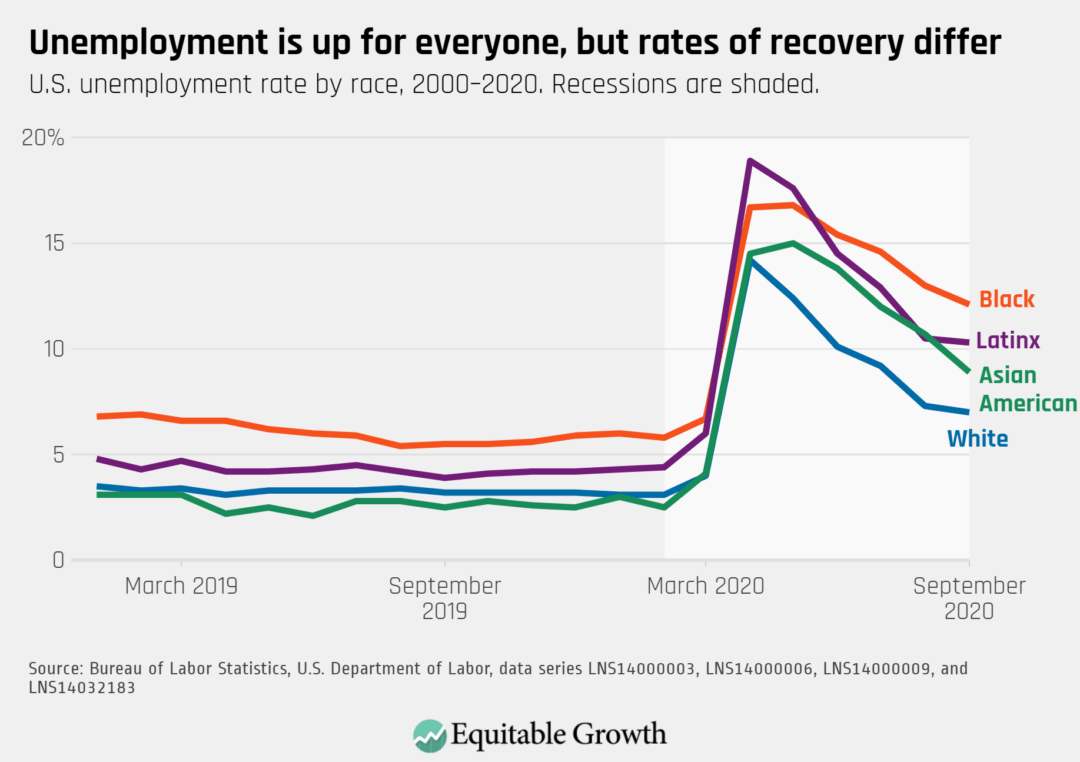

At 7 percent, White workers’ unemployment rate is well-below the 8.9 percent jobless rate for Asian American workers, the 10.3 percent jobless rate for Latinx workers, and the 12.1 percent jobless rate for Black workers. The unemployment rate for women, which was lower than the jobless rate for men just before the onset of the coronavirus recession, stands 0.3 percentage points above it, at 8 percent. Additionally, 865,000 women dropped out of the labor force in September, and therefore are no longer counted among the ranks of the unemployed. Longstanding disparities along the lines of race, ethnicity, and gender continue to be exacerbated amid the tenuous economic recovery.

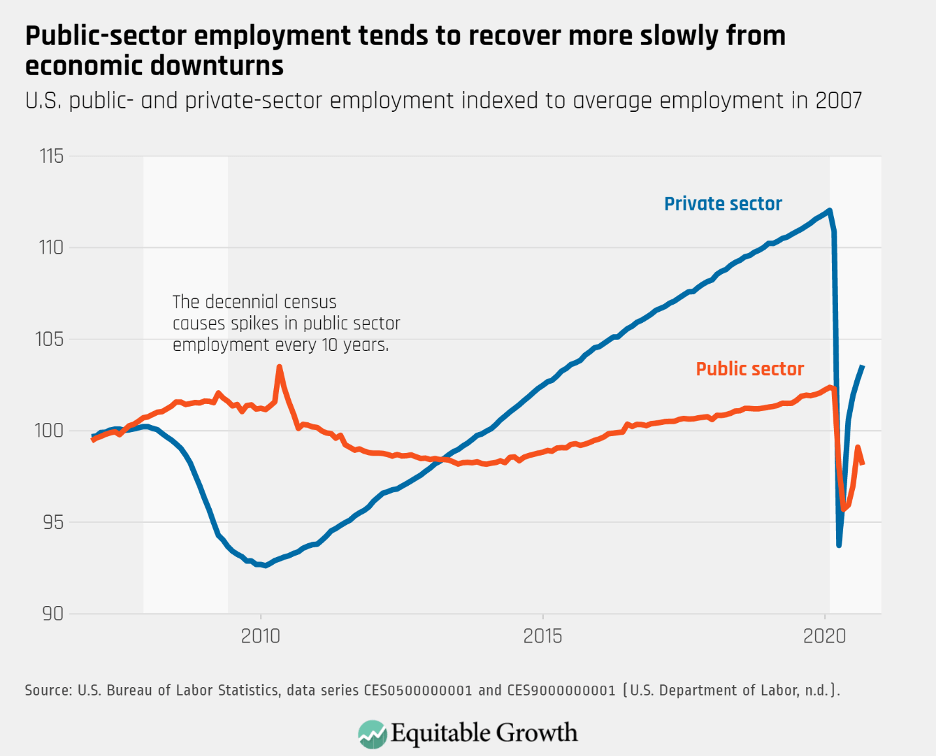

So far, employment losses in the public sector are not as deep as in the private sector, but they are worrying given that government is the only major sector to have experienced net losses last month, shedding 216,000 jobs in September. Additionally, the public sector was exceptionally slow to recover from the previous economic downturn. Even though the private sector also took a harder hit during and immediately after the Great Recession of 2007–2009, jobs were back to their pre-crisis level by March 2014. In contrast, government employment did not fully bounce back until late 2019, excluding a brief spike in 2010 due to hiring for the past decennial Census. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The crisis in the public sector also threatens many good jobs. Government workers tend to be less likely than their private-sector counterparts to experience either job losses or poverty, and have greater access to employee benefits such as healthcare. At 33.6 percent, the union membership rate of government workers is five times greater than for private-sector workers. Since the 1960s, effective enforcement of equal opportunity employment policies and greater political power led to a rise in the share of Black workers holding government jobs, making the public sector an important pathway to economic mobility and security for many marginalized workers.

Over the past few decades, however, public-sector jobs are becoming more insecure and less effective at promoting equitable labor market outcomes—a process that Great Recession of 2007–2009 seems to have accelerated.The past 40 years are marked by a shift from decent to lousy jobs, with both the decline in public-sector job quality and the loss of government jobs through recessions contributing to rising economic inequality. Research by Kimberly Christensen of Sarah Lawrence College, for example, shows that the fiscal crunch faced by state and local governments in the aftermath of the Great Recession was particularly damaging for women workers and workers of color because it shifted employment from good government jobs to much more precarious work in retail, leisure, and poorly paid medical care work.

Even though government jobs used to serve as a buffer against U.S. labor market inequality, their equalizing effect weakened over time. When analyzing racial disparities in the likelihood of being laid off, Elizabeth Wrigley-Field of the University of Minnesota and Nathan Seltzer from the University of Wisconsin-Madison find that Black workers are more likely to involuntarily lose their jobs than White workers, a disparity that has increased since the 1990s. The public sector used to reduce Black workers’ disproportionate exposure to layoffs, but it became less protective over the past three decades, the authors find.

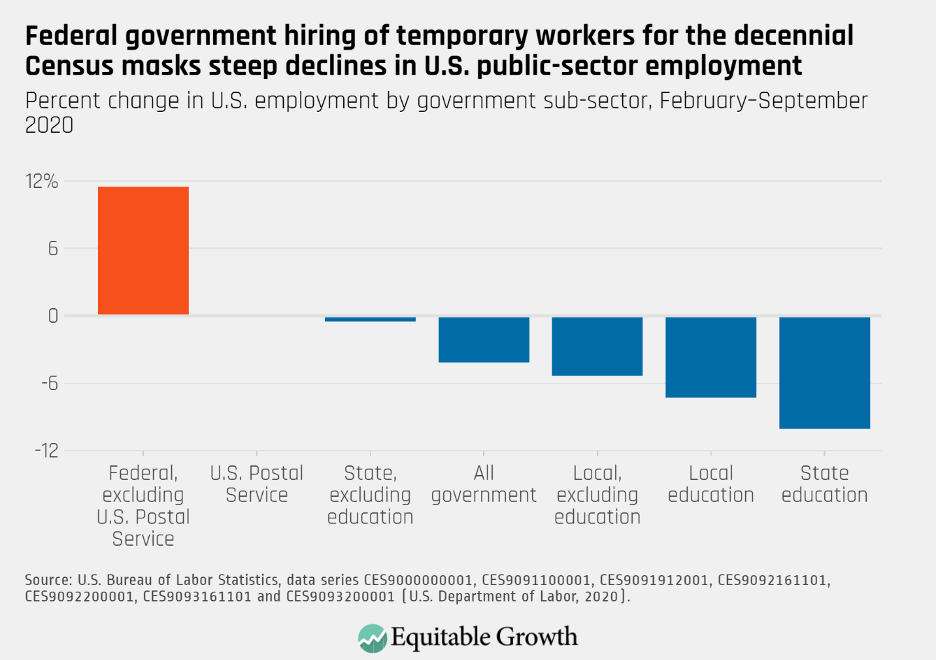

The great majority—63 percent—of public-sector workers are employed in local governments, compared to 23 percent in state governments and 14 percent in the federal government. This means local and state government workers—among whom women and Black workers make up a larger share of the labor force than in the federal government—are once again experiencing the deepest job losses because states are required to keep balanced budgets without debt financing.

In addition to the downward pressure on state and local employment in recessions, the increase in federal employment over the past 6 months is due to this year’s decennial Census staffing. This staffing is now beginning to wind down. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Another slow recovery in the public sector—a sector in which Black workers, women workers, and union members are overrepresented—would put the brakes on the economic security they and their families need to climb out of the coronavirus recession, deepen existing U.S. labor market disparities, and become a drag on the economic recovery, as consumer spending declines as more quality jobs disappear.As state and local governments struggle with deep revenue and budget shortfalls, greater fiscal support to state and local governments is essential.

In addition to the unique risks facing the public sector, the private sector faces challenges to continuing jobs growth as well. These challenges exist in the public sector, too, particularly jobs such as Kindergarten through 12th grade school teachers, but private-sector service jobs that require face-to-face interaction or require close proximity to one’s co-workers during an uncontrolled pandemic means that many of the recent jobs gains remain precarious.

Without sweeping and coordinated public health measures in place and effective treatments and vaccines for COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, the number of additional jobs gained amid this tenuous economic rebound is fragile, and these jobs remain hazardous. The upshot: This continuing recession is still exacerbating long-term trends of decreasing job quality and rising economic precarity, which are especially harmful to marginalized workers, including Black workers and women workers, and their families, particularly amid a still-lethal pandemic.

Equitable Growth’s Jobs Day Graphs: September 2020 Report Edition

On October 2nd, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released new data on the U.S. labor market during the month of September. Below are five graphs compiled by Equitable Growth staff highlighting important trends in the data.

The employment-to-population ratio for people in their prime working years fell slightly from 75.3 percent to 75.0 percent in September, signaling a stalling recovery for the labor market.

The unemployment rate for Black and Latinx workers remains in double digits at 12.1 percent and 10.3 percent, respectively, remaining significantly higher than White and Asian American workers. In May, Asian American workers saw an unprecedented increase in unemployment, which later fell but remains elevated above White workers.

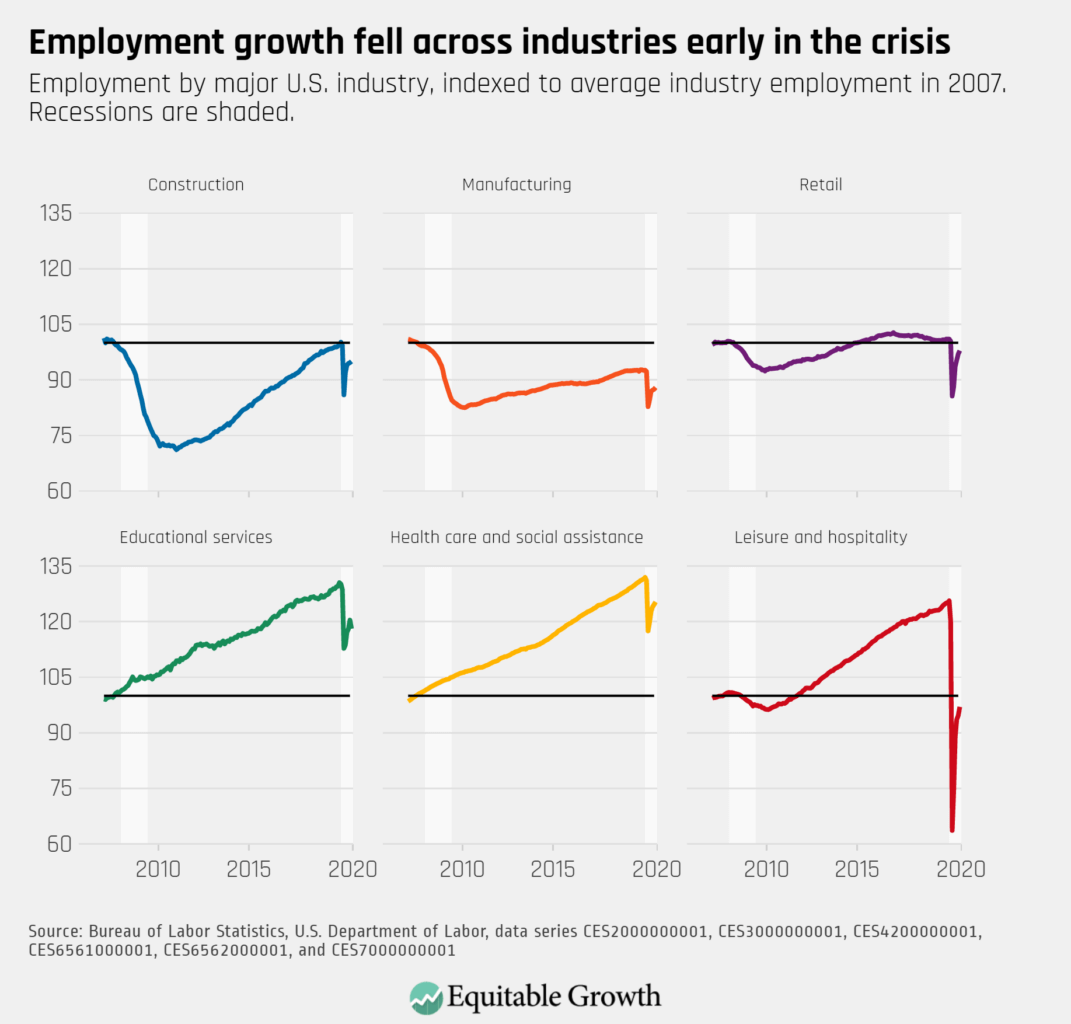

Employment growth slowed across all industries and fell in education services.

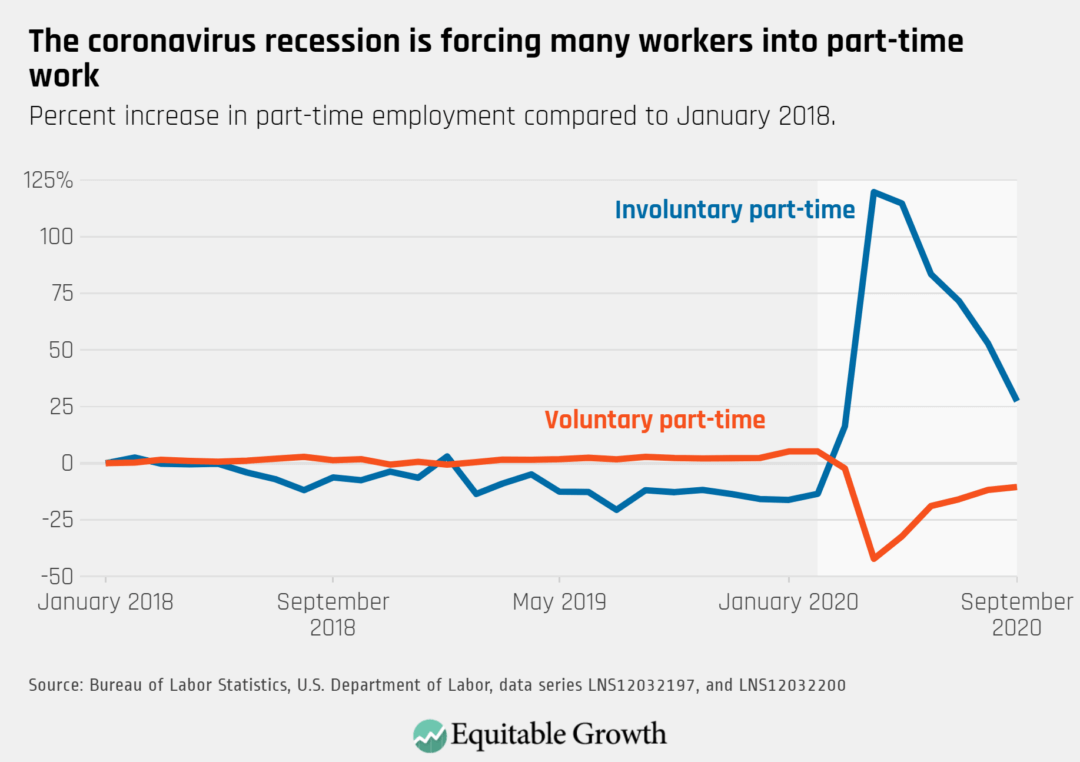

Involuntary part-time work fell by 1.3 million jobs, but still remains 2 million higher than in February before the crisis.

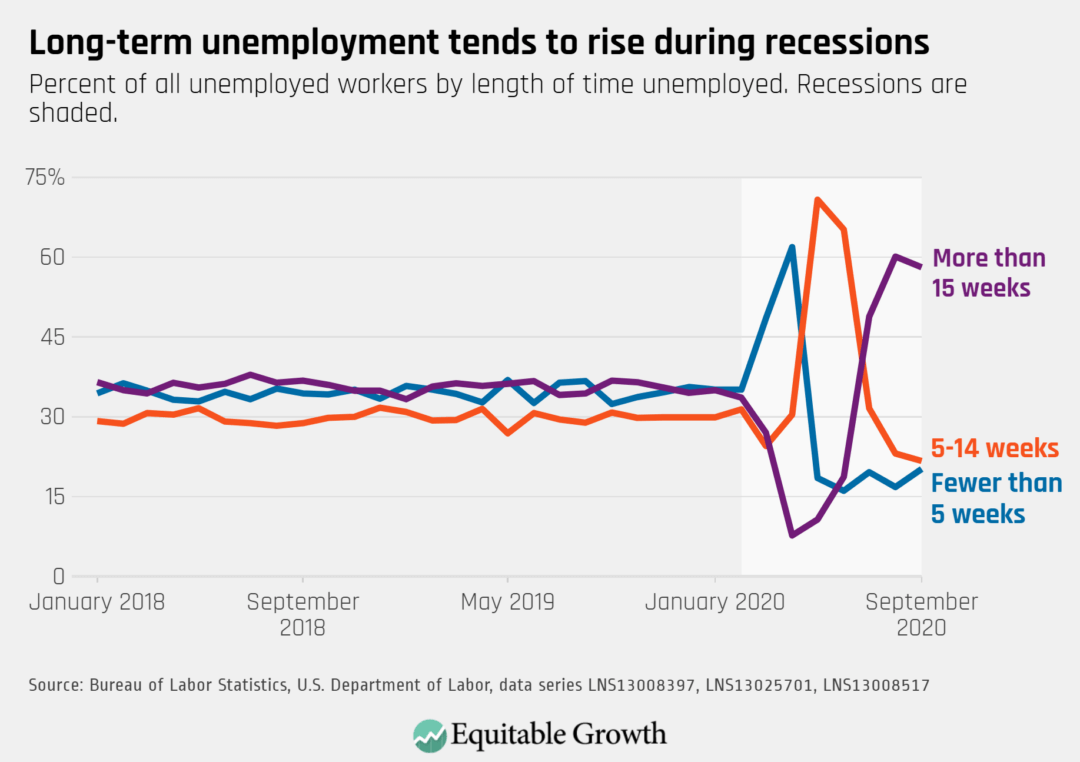

The proportion of those unemployed who have recently lost a job rose by 271,000 in September, reflecting new layoffs as the coronavirus recession continues.

Testimony by Michael Kades before the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law on digital markets

Michael Kades

Director, Markets and Competition Policy

Washington Center for Equitable Growth

“Proposals to Strengthen the Antitrust Laws and Restore Competition Online”

Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law

October 1, 2020

Thank you Chairman Cicilline and Ranking Member Sensenbrenner and full committee Chairman Nadler and full committee Ranking Member Jordan for the honor of testifying before this Subcommittee on competition and digital markets.

I am the Director of Markets and Competition Policy at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. We seek to advance evidence-backed ideas and policies that promote strong, stable, and broad-based economic growth. The exploitation of monopoly power across the U.S. economy threatens innovation, stifles growth, and exacerbates inequality.

Digital marketplaces play an increasingly important role in the economic life of every American. The novel coronavirus pandemic has only increased their significance. The Judiciary Committee should be commended for conducting a bipartisan investigation into the state of competition in online markets and issuing its report.

I encourage the Committee not to stop with the report. The challenges we face are not limited to one or two companies. The filing of one or two cases will not solve our problems. The committee has an important role to play in promoting competition in digital markets. There are three issues, I urge you to consider as you move forward.

Legislative Reforms

First, we need legislation, not just enforcement actions. This may sound obvious, but legal requirements should efficiently distinguish procompetitive conduct from anticompetitive conduct. Over the past 40 years, however, the federal courts, showing an almost neurotic fear of overenforcement, have increased burdens on plaintiffs in antitrust cases and narrowed the scope of antitrust law.

One example underscores this point. Arguably, the most significant monopolization case in U.S. history was the government’s successful break-up of the American Telegraph and Telephone Company in the 1980s. Under current case law, it is questionable that the government could pursue its claim under today’s standards. This development should shock every member of Congress. But it is of particular concern because the central issue in AT&T was its refusal to connect its long-distance competitor MCI to local phone exchanges—in other words, freezing out competitors—one of the major concerns raised in the course of the Committee’s investigation. My written testimony includes a letter I signed with 11 other economists and lawyers. (see Appendix A). All of them have served in the government. Many of them have defended companies in antitrust investigations. And all of them agree that

the antitrust laws, as interpreted and enforced today, are inadequate to confront and deter growing market power in the U.S. economy and unnecessarily limit the ability of antitrust enforcers to address anticompetitive conduct in the digital markets that the Committee is investigating.

That letter I signed provides a number of suggested reforms to restore the vitality of the antitrust laws, which

- Nullify existing precedent that limits antitrust actions,

- Clarify that the antitrust laws protect potential competition,

- Establish legal rules that, in appropriate cases, require defendants to prove their conduct does not harm competition, and

- Increase penalties and enforcement resources

The courts have made it abundantly clear that they believe the antitrust laws have little role to play in promoting competition because the market can fix itself. And, therefore, do no harm is the prevailing approach. Unless Congress takes a different view by passing legislation, dominant firms will have little concern about the antitrust laws limiting their conduct.

Remedies that address entry barriers: Interoperability

None of this is to suggest that the government should shy away from prosecuting antitrust violations against digital platforms. To the contrary, the antitrust enforcement agencies have a duty to attack monopoly power where they find it and to advocate for courts to update and modify their doctrines to conform to modern economic theory.

This leads me to my second point. Remedying antitrust violations in digital markets will be challenging. As this committee has heard consistently, whether it be a social network such as Facebook, an online marketplace such as Amazon, an App Store, or Google’s search product and online advertising eco-system, network effects are a fact of life. The more people using a digital platform, the more valuable it is. In turn, the markets tend to tip toward a single firm.

These dynamics make anticompetitive conduct more likely to be successful and it will often target small, nascent, or potential competitors. This makes it harder to challenge conduct and to develop remedies that will restore competition. Moreover, once an antitrust violation has occurred—once a company has obtained or maintained a dominant position through exclusionary conduct—restoring competition and preventing future violations requires a remedy that diminishes those entry barriers. As result, simply banning conduct, financially penalizing a company, or even breaking up a company may not be sufficient.

Interoperability, which broadly defined means requiring connections between platforms can be an effective tool to diminish entry barriers. (See Appendix B). For a social network, interoperability is likely a necessary, but not necessarily a sufficient, condition for an effective remedy to an antitrust violation. Users will not switch to a new social network until their friends and families have switched.

Interoperability causes network effects to occur at the market level – where they are available to nascent and potential competitors – instead of the firm level where they only advantage the incumbent. Interoperability allows someone who is not a member of the dominant social network to continue to communicate with friends or families on that platform. Just like a person with Verizon can text a person with T-Mobile, interoperability would allow a person on one social network to share posts and pictures) with a friend on another social network.

Without interoperability, it would be difficult to undo the damage done by excluding competition, and the dominant firm has the same incentives to find new way to prevent competition.

Regulations that Promote Competition

Third, the Committee should focus broadly on the goals of promoting competition and not narrowly on specific tools. Strong antitrust enforcement is an important tool, but it is not the only tool. Laws and regulations can also promote competition. Reports from the U. K.’s Competition and Markets Authority, the Stigler Center, the European Union, and the Shorenstein Center all conclude that the solutions are not a choice between antitrust enforcement and regulation but rather both. Regulations, broadly understood, can establish marketplace rules that promote competition and ensure that competition occurs on dimensions that consumers value, such as quality, rather than deceiving or steering consumers into making poor choices. Regulations can also limit the harms that fall outside of traditional competition concerns such as labor, the environment, and speech issues.

I do not mean old-fashioned, utility-style regulation but regulations that level the playing field, promote entry, and increase competition. The Carterfone rule created competition in the sale of phones, fax machines, and modems. The Hatch-Waxman Act created vibrant price competition in pharmaceutical markets that saves consumers tens of billions of dollars every year.

Focused regulation can often reach important issues, such as privacy and protecting consumers’ data, more efficiently and quickly than litigation-based antitrust enforcement. As the committee considers how to promote and protect competition in digital markets, it is good to remember that the greatest successes in competition policy have typically come when antitrust enforcement and regulation complement each other as they did in eliminating AT&T’s phone service monopoly. That approach is likely to apply with equal force to today’s challenges in digital markets.

Protecting competition in digital markets requires laws that efficiently distinguish pro and anticompetitive conduct, remedies that address the underlying network dynamics, and a combination of antitrust enforcement and regulation so that markets the deliver the results that benefit us all.

Thank You, and I look forward to answering your questions.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Interoperability as a competition remedy for digital networks

Why cost-benefit analysis of tax regulations has failed, and how to fix it

When President Donald Trump signed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act into law in December 2017, he kicked off an incredible period of regulatory activity at the U.S. Department of the Treasury and the IRS because the two agencies then had to clarify the meaning of the often-ambiguous new law. The regulations that the agencies subsequently issued define terms, detail calculations, and generally explain what the agencies understand the law to mean. In early 2018, while this process was going on, the Trump administration also expanded a requirement for cost-benefit analysis of tax regulations so that it applied to many more tax regulations than it had in the past.

More than 2 years later, it is clear this experiment in cost-benefit analysis of tax regulations has failed. In a new report released today, I document the shortcomings of the cost-benefit analyses issued for regulations implementing the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, explain why those weaknesses are rooted in the framework for cost-benefit analysis mandated by the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, which oversees such analyses, and recommend an alternative approach for the analysis of tax regulations led by the Treasury Department.

The cost-benefit analyses released alongside regulations implementing the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act provide little information relevant to assessing the merits of those regulations. Evaluating the merits of a tax regulation requires assessing the impacts of that regulation on revenues and burden. Do the revenue losses prevented justify the tax burden imposed by a more stringent interpretation of the law, taking into account who would bear that tax burden? Or does the burden reduction, taking into account who would benefit, justify the revenue loss? The cost-benefit analyses that the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs instructs agencies to produce cannot answer these questions.

Moreover, while tax experts criticize many TCJA regulations for providing unmerited windfalls to favored groups, the cost-benefit analyses for those regulations often fail to identify these windfalls or provide critical analysis of them. Regulatory giveaways in the interpretation of the new deduction for income from pass-through businesses, the tax on global intangible low-taxed income, and the base erosion and anti-abuse tax, for example, all were subject to little or no critical analysis.

If decision-makers within the Department of the Treasury and the IRS used these analyses to guide their regulatory choices, they would likely be making less informed choices than they would if they simply ignored the analyses.

The weaknesses of these analyses are rooted in the framework that the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs mandates for the cost-benefit analysis of federal regulations. This framework is fundamentally ill-suited to the evaluation of tax regulations for two main reasons.

First, the framework treats revenue impacts as neither a cost nor a benefit even though raising revenues is the primary purpose of taxation. Lax regulatory interpretations that generate windfall gains for recipients often have few or no costs. Indeed, a regulation that simply gives up on preventing some form of corporate tax avoidance could generate net benefits in this framework because corporations would face a reduced cost of avoiding taxes, and the revenue loss itself would not be treated as a cost. Regulatory giveaways in the implementation of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act probably avoided critical scrutiny in part because the analytic framework does not conceive of the revenue loss from those giveaways as a cost and thus does not focus attention on them.

Second, the framework relegates changes in the distribution of the tax burden to second-tier status. Though it may seem neutral to instruct the Treasury Department and the IRS to ignore changes in the distribution of the tax burden in assessing the costs and benefits of tax regulations, it is not. High-wealth taxpayers are generally better able to avoid paying taxes than low-wealth taxpayers. This framework thus puts a thumb on the scale for reallocating taxes from the wealthy to everybody else. The reduction in tax avoidance is deemed a benefit while changes in the distribution of the tax burden are deemed neither a cost nor a benefit. Indeed, though the framework for cost-benefit analysis is often described as disregarding redistributive impacts, it would be more accurate to say that it adopts a specific normative view on how to judge redistributive impacts.

By ignoring revenue and distributional impacts in assessing costs and benefits, this framework biases the analysis in favor of regulatory giveaways and against regulations that protect the tax base.

In light of this performance, the next administration should eliminate the requirement for cost-benefit analysis of tax regulations and the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs’ authority to review that analysis. Instead, the Treasury Department should provide a qualitative and, when feasible, quantitative evaluation of tax regulations grounded in the fundamental considerations of tax policy: impacts on revenues, on the level and distribution of the tax burden, and on compliance costs. These tools are the analog of the cost-benefit framework, taking into account the distinct purpose of tax regulations.

The Department of the Treasury’s analysis of the impacts on revenues, burden, and compliance costs should focus on the decision points where the department and the IRS have discretion to regulate differently, as this is the analysis that would most directly inform regulatory decision-making, and the analysis should be conducted only when the relative impacts of different interpretations of the law are substantial.

In the current framework, cost-benefit analysis hides revenue-losing, inequality-increasing regulatory giveaways behind a technocratic veil. The reformed approach would provide decision-makers with the analysis necessary to make informed choices in service of broadly shared growth.

For more, read the full report.

Brad DeLong: Worthy reads on equitable growth, September 22-28, 2020

Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

1. All issues of differential social power become issues of life and death amid a pandemic. And in our economy and society, possessing money is the road to possessing social power. The surprising thing I find about today is that anything Heather Boushey says in her op-ed in USA Today last week is at all non-consensus. Read her “To recover from COVID-19 Recession, Americans need equitable economic growth,” in which she writes: “Small businesses—the corner store, cafe and diner, alongside the dry cleaner and dog groomer and all the rest—are the backbone of our communities and yet so fragile in this crisis. Indeed, policies that promote equitable growth across the income spectrum are essential if we want an economic recovery that is broad-based and sustainable. The pandemic has also unmasked all the ways that health care is a core economic issue. It starts with the right for workers to have proper protective equipment and be able to stay home when they are sick. These workplace issues have become a matter of life or death.”

2. This is a very useful, near real-time take on what is going on right now, out there in the U.S. economy: Read Austin Clemen, Raksha Kopparam, and Carmen Sahchez Cumming, “Equitable Growth’s household pulse graphs: September 2–14 edition,” in which we document: “More than 50 percent of respondents in households making less than $50,000 reported having experienced loss of employment income since March 13 … The number of workers filing for Unemployment Insurance benefits remains staggeringly high. Out of the major racial or ethnic groups, Black applicants have been the least likely to receive benefits … Nearly a quarter of Latinx, Black, and Asian respondents are behind on rent payments. Additionally, Black respondents are struggling to keep up with mortgage payments … This recession is also hitting those with lower levels of education hardest. More than half of those without a high school degree report having a somewhat or very difficult time paying for usual household expenses.”

3. Carl Shapiro and Hal Varian have long had great success by saying that the information-age economy raises little in the way of questions about antitrust that the First Gilded Age of the late 1800s did not. But that is not quite true. Facebook Inc., for example, poses competition-policy problems more complex and subtle than anything we faced in the Progressive Era. Read the new working paper by Michael Kades and Fiona Scott Morton, “Interoperability as a competition remedy for digital networks,” in which they write: “Addressing entry barriers created by network effects is critical to remedying a monopolization violation in a social network market (e.g. Facebook) … Interoperability is likely a necessary, but not necessarily a sufficient, condition for an effective remedy … in addition to other relief such as a divestiture, and indeed could be complementary to it, or stand on its own. In today’s internet-based network markets, interoperability carries no incremental costs … Developing an effective interoperability scheme from scratch will be challenging in the context of adjudication. Remedy details will be technical, but important, and time will be short. Moreover, interoperability affects multiple parties, not simply the litigants, which the court will want to consider. The adversarial process is poorly suited to addressing these tasks … This working paper describes the general competitive concerns that arise in digital platform markets with strong network effects, explains how requiring interoperability can remedy illegal monopolization by creating the potential for disruptive competition to arise and thrive, addresses how to make an interoperability requirement effective, discusses the problems or dangers of relying solely on adjudication for developing remedies for complex monopolization violations, and explores how rulemaking could ameliorate this challenges, including a proposed draft rule.”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

1. A huge amount—an absolutely huge amount—was lost when Harry Dexter White overrode John Maynard Keynes at Bretton Woods and placed responsibility for closing “fundamental disequilibria” on deficit countries alone. This policy mistake still haunts us. And odds are that it is about to haunt us again. Jeremy Bulow, Carmen Reinhart, Kenneth Rogoff, and Christoph Trebesch sound the alarm. Read “The Debt Pandemic,” in which they write: “The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly lengthened the list of developing and emerging market economies in debt distress. For some, a crisis is imminent. For many more, only exceptionally low global interest rates may be delaying a reckoning. Default rates are rising, and the need for debt restructuring is growing. Yet new challenges may hamper debt workouts unless governments and multilateral lenders provide better tools to navigate a wave of restructuring … So far, the pandemic shock has been limited to the poorest countries and has not morphed into a full-blown middle-income emerging market debt crisis. Thanks in part to favorable global liquidity conditions conferred by massive central bank support in advanced economies, private capital outflows have moderated and many middle-income countries have been able to continue to borrow … Yet … the riskiest period may still lie ahead. The first wave of the pandemic is not over … On top of the dramatic retreat in private funding, remittances from emerging market citizens working in other countries are expected to drop by more than 20 percent this year. At the same time, borrowing needs have skyrocketed.”

2. Well, a decade late and many dollars short we seem to have become the conventional wisdom! Would only that The Economist had listened to our arguments, and been on our side a decade ago! Read, “Governments can borrow more than was once believed,” in which the magazine writes: “The global financial crisis pushed rates around the world to near zero … In 2012 Larry Summers, a former American treasury secretary, and Brad DeLong, an economist, suggested a large Keynesian stimulus based on borrowing. Thanks to low interest rates, the gains it would provide by boosting the growth rate of GDP might outstrip the cost of financing the debt taken on … As the years went by and interest rates remained stubbornly low, the notion of borrowing for fiscal stimulus started to seem more tenable, even attractive … Governments ideally ought to make sure that new borrowing is doing things that will provide a lasting good, greater than the final cost of the borrowing. If money is very cheap and likely to remain so, this will look like a fairly low bar.”

3. I do not think we understand who the median effective investors in financial markets are, and why they think what they do. Read John Auther, “It’s a Weird World Where FANGs Are a Haven Asset,” in which he writes: “FANG popularity in large part rests on the perception that they are defensive. Thanks to their entrenched competitive position, and relative immunity to the pandemic, they are thought to offer safety. Meanwhile, the banks are the polar opposite. Aided by a positive economic cycle, banks also benefit from higher bond yields, which are nowhere to be seen … [Since] March … the 10-year Treasury yield … has oscillated … around that 0.666% level. This is strange because the Federal Reserve isn’t yet formally attempting to control 10-year yields, despite widespread speculation that it will start to do so before long. And views on inflation, usually a key component of nominal 10-year yields, have gone through huge changes during the 0.666% era.”

Weekend reading: Measuring and achieving a U.S. economy that works for all edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

The disproportionate impact of the novel coronavirus and COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, on communities of color, particularly Black and Latinx communities, alongside the continuing police murders of unarmed Black people without consequences demonstrate more than ever that systemic racism is an ongoing problem in the United States. Equitable Growth has long argued for disaggregating economic data to see who prospers when the economy grows, but Austin Clemens and Michael Garvey explain why doing so would have an additional important result—putting on full display the profound effects of racism across our economy and society, from healthcare to wealth accumulation to the criminal justice system and more. Clemens and Garvey detail how Congress and the executive branch can improve our understanding of economic and social outcomes for communities of color, including improving data collection, performing deeper analyses of racial economic divides, and providing policymakers with a better idea of the needs of marginalized communities in the United States. Specifically, they push for oversampling of communities of color with regard to existing federal surveys and data collection efforts to ensure the data collected is as robust as possible.

Earlier this week, the U.S. Census Bureau released new data on the effects of the coronavirus pandemic on workers and households. Austin Clemens, Raksha Kopparam, and Carmen Sanchez Cumming put together four graphs highlighting important trends in the data—namely, that low-income workers, those with less education, and workers of color are struggling the most amid the coronavirus recession.

Prioritizing stock market growth and using it as the barometer of economic expansion provides an inaccurate look at how the U.S. economy is actually working for workers and their families, writes John Sabelhaus. He explains the hidden costs of only looking at the stock market’s performance but not examining why it has gone up and the policies that increase stock prices at the expense of other things, such as adequate wages or Medicare and Social Security funding. He dives into what moves the stock market up and down, and the government’s role in these booms and busts, to show why stock-market-first economists are wrong to focus on policies that generate stock-price growth rather than a stronger economy for all. Sabelhaus then turns to recommendations for how policymakers should act to spur broadly shared economic growth, including investing in our workforce, infrastructure, innovation, and technology, and, importantly, ignoring the oft-told idea that making wealthy people wealthier will produce trickle-down effects for the rest of us (it doesn’t). Stock-market-first approaches have deepened wealth inequality in the United States, he writes, and those who benefit from a booming stock market are not the same people who are sacrificing so much, particularly during the coronavirus recession.

Policy decisions made over the past half-century weakened the U.S. economy and restricted growth, making the nation more vulnerable to crises such as those we are currently experiencing. We need new policies that support equitable economic growth across the income spectrum in order to truly recover from the coronavirus recession, writes Heather Boushey in an op-ed for USA Today. Lawmakers must enact policies, including paid sick leave, affordable child care and universal pre-Kindergarten, a livable minimum wage, expanded Unemployment Insurance, and small business support systems, Boushey continues—and policymakers must ensure these benefits are triggered on and off automatically. Without automatic stabilizers, economic aid to hard-hit populations in future recessions could be hamstrung by politics, much like the next round of coronavirus relief aid, which is currently stalled in Congress.

Competition among big technology firms is a hot topic, with rumors that Facebook Inc. and Alphabet Inc.’s Google unit may soon face monopolization cases against them. The previous major monopolization case was filed in 1998, against Microsoft, but much has changed since then. Michael Kades and Fiona Scott Morton propose that instead of questioning whether monopolization is occurring, we look at remedies for such violations of antitrust laws. In a recent working paper and accompanying Competitive Edge post, they design a remedy for addressing monopolization by a social media network based on five principles: the network effects of social networks, the entry barriers these network effects create, interoperability, the legal and technical challenges of implementing interoperability, and the role of the Federal Trade Commission’s rulemaking authority in drafting interoperability orders. They then explain each of these five areas and their relevance to designing a remedy to address monopoly violations by social media networks.

Links from around the web

A new study by Citigroup Inc. shows that the U.S. economy lost $16 trillion as a result of discrimination against African Americans since 2000. This is a significant amount, writes Adedayo Akala for NPR, especially when you consider that U.S. Gross Domestic Product totaled $19.5 trillion in 2019. The study breaks down the $16 trillion figure in four key divides between Black and White Americans: lost business revenue from discriminatory lending practices for African American entrepreneurs ($13 trillion); lost income from wage discrimination ($2.7 trillion); lost wealth accumulation thanks to housing discrimination ($218 billion); and lifetime income lost from discrimination in access to higher education opportunities ($90 billion). And that’s not all, Akala reports. The study’s authors also estimate a $5 trillion price tag over the next 5 years for not acting immediately to eliminate racial discrimination, before providing several recommendations for how policymakers can reverse these racial divides.

At the start of the coronavirus recession, the Federal Reserve jumped into action to stabilize the U.S. financial system, which was going haywire as a result of the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic. With stock markets back to pre-pandemic levels, it appears the Fed’s quick action worked, writes Neil Irwin for The New York Times’ The Upshot—perhaps too well. The success of these efforts may have removed the urgency for lawmakers to pass legislation that would extend relief aid to average Americans. This mentality of Wall Street over Main Street means a difficult economic reality today for many workers—especially low-income, less-educated, Black, and Latinx workers, who, as the data show, are being hardest hit by the recession—and small businesses, which are struggling even as large corporations experience record profits. Similar actions focused on rescuing financial systems rather than individuals were taken during the Great Recession of 2007–2009, Irwin writes, which led to a recovery so sluggish that many families were only just beginning to get back on their feet when the virus took hold earlier this year.

The Unemployment Insurance system in the United States is broken, writes Vox’s Emily Stewart. But it doesn’t have to be. Telling the story of one working mother in California, Stewart looks at how workers have been harmed by the UI system’s shortcomings and complexities during the coronavirus recession as well as before the onset of the pandemic. Stewart then examines the ways policymakers can improve how unemployment benefits are delivered and actions they can take to ensure that those who need help are able to access it with ease. Reimagining the UI system “would treat the jobless like customers, not criminals, while helping them stay afloat as they find their next gig,” she writes, making it easier to navigate and ensuring more consistent pay regardless of where workers live.

We lost a key figure in the fight for gender equality last week. Over the course of her career, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg made it possible for women to gain access to credit and wealth building opportunities, to access the same jobs as men and get paid the same when they did, and generally making society, the labor market, and the economy more equitable. The Atlantic’s Joe Pinsker runs through Ginsberg’s legacy and how it brought about changes to areas of daily life that we take for granted nowadays, including gender roles in the household and the labor force. Though the United States has hardly achieved gender equality, Pinsker continues, without a doubt, Ginsberg pushed us closer.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Structural racism and the coronavirus recession highlight why more and better U.S. data need to be widely disaggregated by race and ethnicity” by Austin Clemens and Michael Garvey.