Competitive Edge: Underestimating the cost of underenforcing U.S. antitrust laws

Antitrust and competition issues are receiving renewed interest, and for good reason. So far, the discussion has occurred at a high level of generality. To address important specific antitrust enforcement and competition issues, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth has launched this blog, which we call “Competitive Edge.” This series features leading experts in antitrust enforcement on a broad range of topics: potential areas for antitrust enforcement, concerns about existing doctrine, practical realities enforcers face, proposals for reform, and broader policies to promote competition. Michael Kades has authored this contribution.

The octopus image, above, updates an iconic editorial cartoon first published in 1904 in the magazine Puck to portray the Standard Oil monopoly. Please note the harpoon. Our goal for Competitive Edge is to promote the development of sharp and effective tools to increase competition in the United States economy.

For much of the past three-and-a-half decades, courts across the United States increasingly accepted that strict antitrust rules present far greater dangers than lenient rules. According to this theory, overly strict antitrust rules limit business conduct in two ways. Conduct that is beneficial is wrongly condemned (what is known as a false positive), and the rule deters companies from undertaking procompetitive actions. Further, once an overly strict legal rule is enshrined in precedent, it is difficult to change and has a long-lasting harmful event. In contrast, overly lenient antitrust rules allow anticompetitive conduct to go unpunished (what is known as a false negative), but market forces will correct those problems more quickly than it takes to overturn precedent.

Courts have relied on concern about false positives to limit rules regarding refusals to deal, predatory pricing, and proof of conspiracy, as well increasing the procedural requirements for plaintiffs. This policy, however, has no basis in theory and little empirical support. The evidence that does exist suggests underenforcement is costly. A fuller discussion on this issue (called error-cost analysis) occurs in section 2 of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth’s comments on the Federal Trade Commission’s Hearings Competition and Consumer Protection in the 21st Century.

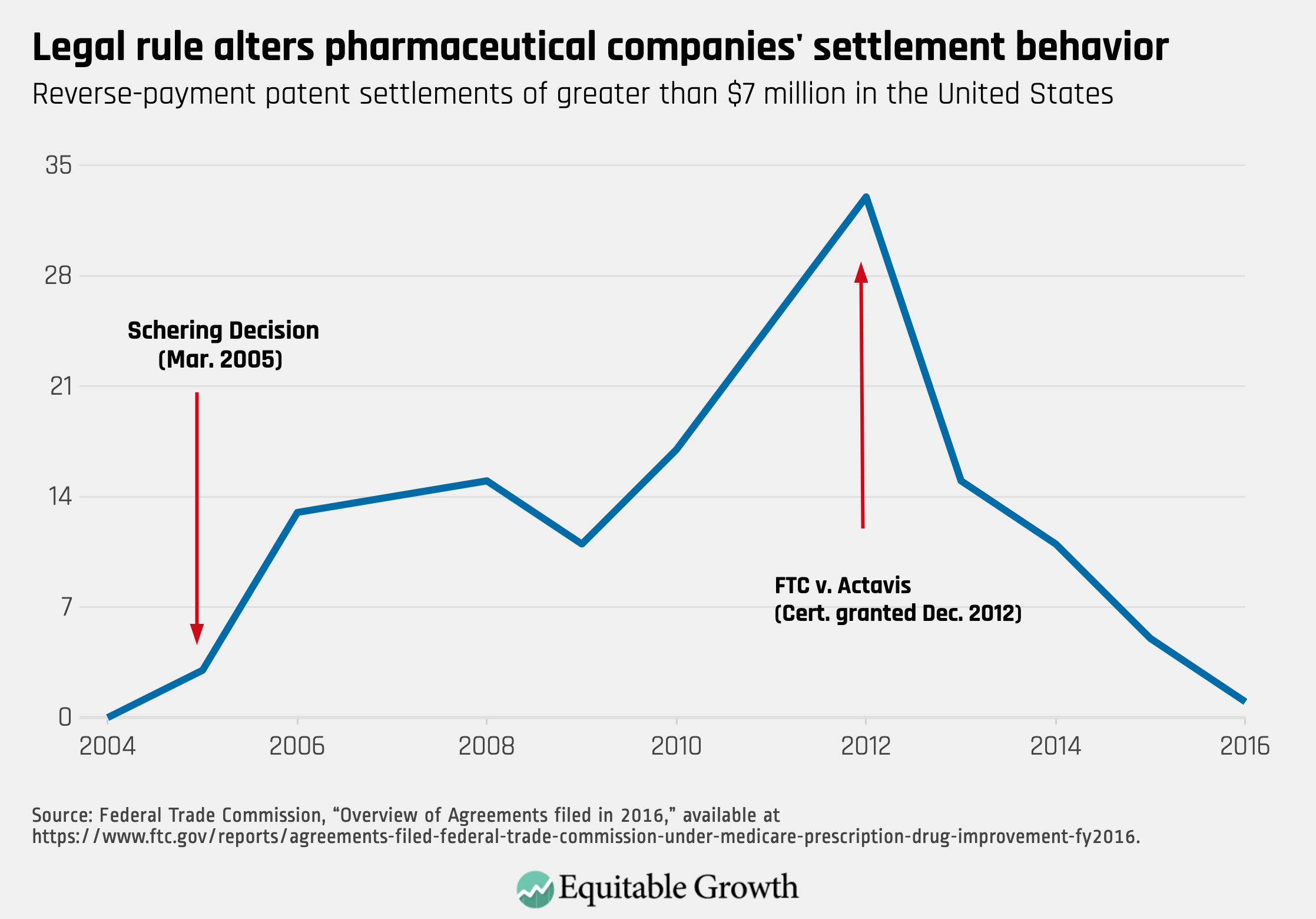

Recent experience with U.S. antitrust rules and pharmaceutical patent settlements provides further evidence that overly lenient rules are costly, and fears of overly stringent rules can be overstated. Between 2005 and 2013, federal courts adopted a lenient rule that allowed patent holders to pay alleged infringers to stay off the market until the patent expired, fearing the dangers of overenforcement and discounting the dangers of this type of settlement. In 2013, the Supreme Court rejected this approach and subjected settlements to antitrust scrutiny in its Federal Trade Commission v. Actavis Inc. decision. Post-Actavis, some scholars argue that the decision will lead to false negatives in some cases, but others conclude false negatives are very unlikely.

Based on the history of reverse-payment settlements, antitrust rules matter. After the courts adopted the lenient rule, the number of settlements with substantial payments increased dramatically, from zero in fiscal year 2004 to a high of 34 in FY2012. Those deals increased prescription drug costs by $63 billion. After 2013, the problematic deals virtually disappeared, and there is no evidence that this stricter rule prevented settlements, limited innovation, or suppressed patent challenges—the primary policy concerns of courts adopting the scope of the patent test relied upon.

Background on pharmaceutical patent settlements

Competition from low-cost generics is one of the few proven ways to control prescription drug prices. Often, that competition depends on the outcome of patent litigation between the firm that owns the branded drug and the one planning to sell a generic alternative over whether the branded firm’s patents are valid and whether the generic product infringes on those patents. Beginning in the 1990s, branded and generic companies found a new way to settle patent litigation. A branded company would allege that its potential generic competitor’s product infringed on the branded company’s patent, yet the branded company would pay the generic to stay off the market for a period of time, which is known as a pay-for-delay, or reverse-payment, patent settlement.

The anticompetitive threat is straightforward (a fuller discussion can be found here). The generic company is a potential competitor (whether the branded company’s patent blocks competition is uncertain) and receives payment to accept the branded company’s proposed entry date. The agreement eliminates potential competition and protects the branded company’s monopoly. In turn, the payment compensates the generic company for accepting a later entry date, which delays competition. Consumers are worse off because, in an expected sense, they wait longer for competition and pay higher costs for the product.

The combination of the payment and the restriction on the entry of a new generic drug into the market creates the competition concern. A procompetitive settlement reflects the strength of the patent and occurs when the generic company and the branded company settle a patent suit by splitting the remaining time on the patent. If the patent expires in 10 years, for example, then the generic company might receive a license to the patent in 6 years, guaranteeing 4 years of competition. Without a payment, the settlement simply reflects the parties’ estimates of the strength of the patent.

In contrast, a firm that owns the branded drug will pay the generic alternative to accept an entry date only if the settlement delays generic competition beyond what the patent strength warrants. The generic firm will accept a later entry date only if it is compensated. So, in the example above, a branded company would only pay the generic firm if the generic firm agreed to delay entry more than 6 years, and the generic firm would agree to delay entry more than 6 years only if it is paid.

The Federal Trade Commission, private plaintiffs, and state attorneys general brought a series of cases challenging reverse-payment settlements in the late 1990s. According to them, any payment that was more than de minimis raised significant antitrust concerns and was likely anticompetitive. In March 2005, however, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, in Schering Plough Corp. v. Federal Trade Commission, reached the opposite conclusion. It suggested that, with limited exceptions, reverse-payment settlements were legal unless the generic company agreed to stay off the market until after the patent expired, also known as the “scope-of-the-patent” rule. Two other circuits shortly thereafter adopted this position.

In adopting this lenient rule, courts expressed concerns about the costs of an overly strict rule. Specifically, the courts variously argued that:

- An overly strict rule would “discourage settlement of patent litigation” (see Federal Trade Commission v. Actavis, 570 US 136, 170 (Roberts C.J., dissenting)) because litigation can be costly and inefficient, and limiting settlements could, the courts reasoned, just increase costs to everyone.

- Limiting patent holders’ settlement options could “decrease product innovation by amplifying the period of uncertainty around the drug manufacturer’s ability to research, develop, and market the patented product” (see Schering Plough Corp. v. Federal Trade Commission, 402 F.3d 1056, 1075, 11th Cir. 2005) because if patent holders have fewer settlement options, then the uncertainty of litigation might deter them from investing in research and development.

- An overly strict rule would “reduce the incentive to challenge patents by reducing the challenger’s settlement options” (see Asahi Glass co. v. Pentech Pharms, Inc., 289 F. Supp. 2d 986, 994, ND Ill 2003) because if generic companies could not resolve patent litigation by getting paid, then they might not undertake their challenges in the first place.

At the same time, these courts were confident that even if settlements with payments were anticompetitive, the market would quickly remedy the situation. Once the branded company paid off one generic competitor, that payment would entice other generic companies to challenge the patent. As one court explained, “Although a patent holder may be able to escape the jaws of competition by sharing monopoly profits with the first one or two generic challengers, those profits will be eaten away as more and more generic companies enter the waters by filing their own paragraph IV certifications attacking the patent.”(See Federal Trade Commission v. Watson Pharms, Inc, 677 F.3d 1298, 11th Cir. 2012) In other words, if the branded company paid off one generic firm to avoid competition, then it would face a host of challengers, each demanding a payment to drop their challenges.

In 2013, however, the U.S. Supreme Court put an end to the scope-of-the-patent era and subjected these types of agreements to traditional antitrust analysis. According to the Supreme Court, an agreement in which the branded and generic companies eliminate potential competition and share the resulting monopoly profits likely violates the antitrust laws, absent some justification. (See FTC v. Actavis 570 US 136, 158) The result: The adoption of a very lenient rule, the scope-of-the-patent test, and the change to the stricter rule-of-reason approach provides insight into the costs and consequences of the two regimes.

The cost of the lenient scope-of-the-patent rule

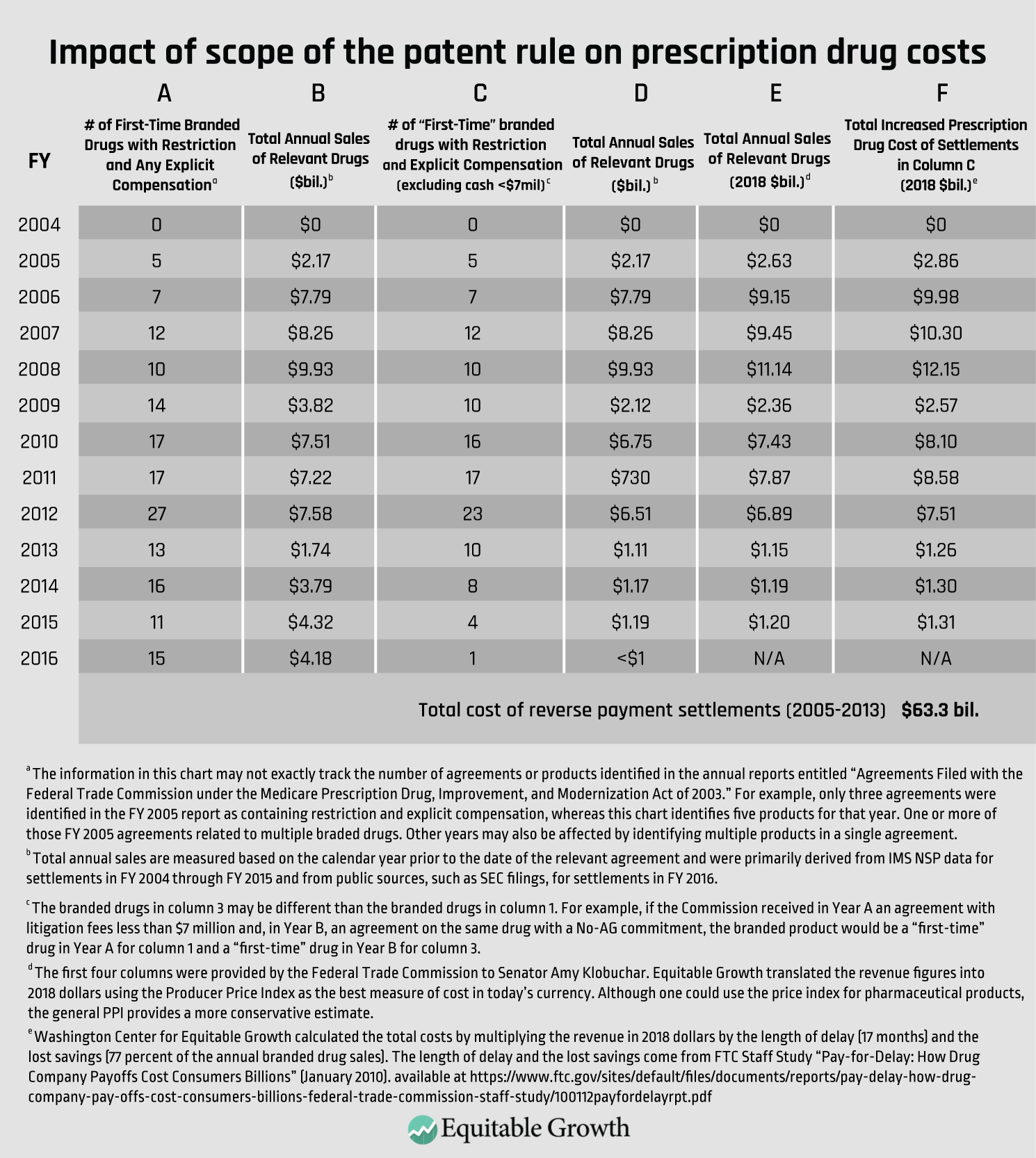

Information from the Federal Trade Commission allows an estimate of the cost to consumers of the scope-of-the-patent rule. The FTC reports the number of settlements with any compensation and the subset of those with compensation greater than $7 million. Adoption of the lenient scope led to a dramatic increase in settlements with substantial compensation (more than $7 million), which peaked in FY2012 at 33. The Supreme Court’s rejection of that rule virtually eliminated settlements with substantial payments. In fiscal year 2016, only a single agreement occurred. The cost of a lenient rule is not simply that anticompetitive conduct goes unpunished; lenient rules also will encourage more anticompetitive conduct. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

One can estimate the cost to consumers of allowing pay-for-delay settlements by multiplying the length of the delay, the lost consumer savings due to delayed generic entry, and the volume of commerce affected. In 2010, the FTC issued a report analyzing pharmaceutical patent settlements. It found that settlements with payments and restrictions on entry delayed generic competition by an average of 17 months relative to settlements without payments. On a yearly basis, consumer lost savings equals 77 percent of the branded drug’s total revenue.

Finally, in information recently provided to Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), the FTC provided statistics on the total revenue of branded drugs subject to patent settlements with restrictions on generic entry and compensation of more than $7 million. The total cost to consumers equals 1.42 years of delay, multiplied by 77 percent of brand product’s revenue, multiplied by the yearly revenue of the branded drugs covered by settlements with compensation above $7 million. As it turns out, the consumer loss is equal to roughly a year of brand sales, or $63.3 billion. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

This estimate may be conservative. The 2010 FTC report counted even de minimis payments as a form of compensation in measuring the average delay. Such deals likely had little or no delay. So, the average length of delay for deals with payments above $7 million is likely longer than 17 months. Of course, more detailed data would allow for a more precise estimate, but it is clear that reverse-payment settlements during the scope-of-the-patent era increased prescription drug costs substantially (in the order of tens of billions of dollars).

It appears the courts adopting the scope-of-the-patent rule underestimate its cost. As a practical matter, during the scope-of-the-patent period, the market response did not deter the practice. Reverse-payment settlements were profitable and successful either because the payments did not entice additional generic companies to challenge the patent or the branded company could pay off all potential competitors. The Supreme Court, in its Actavis decision, explained that for reasons based on the competitive dynamics in the industry, paying off the first generic challenger removed the most motivated challenger. (See FTC v. Actavis at 155.) And, as one article explained, the incentives for subsequent challenges to litigate were so small that they would settle for little or nothing.

The costs of the stricter rule

Many cases are ongoing, and determining whether a given case is a false positive or a false negative requires a case-specific analysis. But what about concerns that a stricter antitrust rule would prevent settlements, deter generic companies from challenging patents, and lower incentives to innovate? Academics have questioned the relevance of those arguments. Whether those concerns are relevant in a legal sense, there is no empirical evidence that they are occurring.

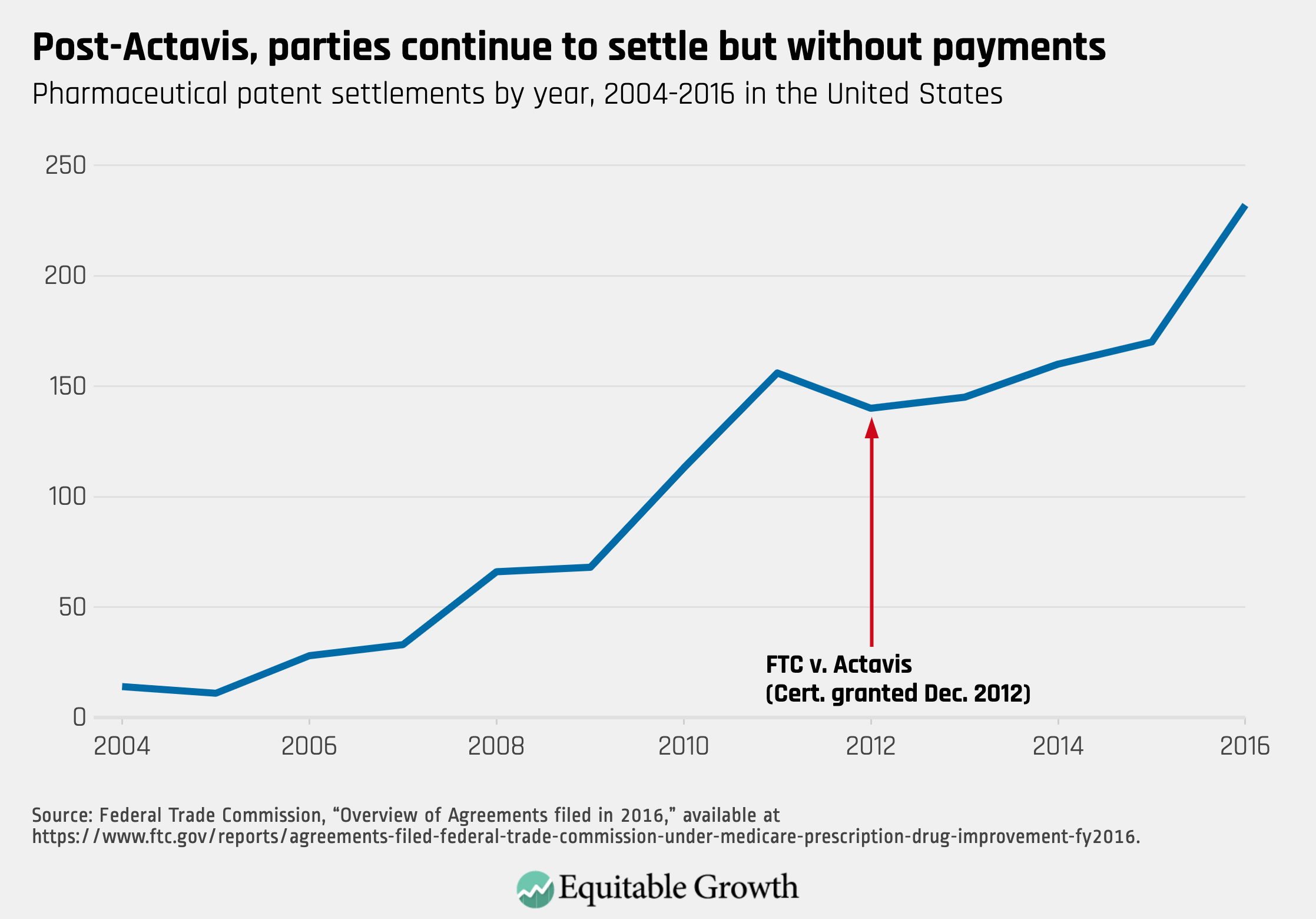

First, stricter antitrust enforcement did not end pharmaceutical patent settlements. Record numbers of settlements occurred in each of the first 3 years after Actavis (FY2014 to FY2016). Although the Actavis decision deterred the use of payments to resolve patent litigation, parties found other ways to settle their disputes that did not harm competition. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Second, there is no evidence that stricter antitrust enforcement deterred innovation. Although it is difficult to determine the impact on research and development, the pharmaceutical industry has not claimed that it is spending less on research and development because of the Actavis decision. To the contrary, PhRMA, the trade association for branded pharmaceuticals, highlights its increased research and development spending.

Third, the Supreme Court’s adoption of a stricter antitrust rule does not appear to have deterred generic companies from challenging patents, based on the 2016, 2017, and 2018 Lex Machina Anda Patent Litigation Reports. In the 4 years preceding the Actavis decision, under the scope-of-the-patent rule, new patent challenges averaged 271 a year, with a low of 236 cases and a high of 293 cases. In the 4 years after the Actavis decision, the average increased to a 413 new pharmaceutical patent challenges yearly, with a low of 326 cases and a high of 476 cases.

Proving a negative—that the Actavis rule did not deter procompetitive settlements—is challenging. The statistics, although they do not establish causation, suggests that the Actavis rule had little, if any, negative impact. Although one can hypothesize that there would be even more settlements, patent challenges, and innovation in the absence of Actavis, the theories are far less plausible, given the descriptive data offered here and lack of qualitative evidence to support them.

Conclusion

Adoption of the scope-of-the-patent test cost consumers more than an estimated $60 billion dollars, with little to no evidence of corresponding benefits. Going forward, courts should be more concerned about rules in this area that are overly lenient than rules that are overly strict. The drug-making industry responded both to the lenient scope-of-the-patent rule and then again to the stricter Actavis rule. Both of these points suggest that an even stronger rule—one that presumes such payments are anticompetitive—may be more effective. It would eliminate the risk of a bad court decision that would substantially increase prescription drug costs, and it would reduce the cost of enforcement.

More generally, contrary to accepted antitrust principles, underenforcement can cause substantial harm, and there should be no presumption that markets by themselves will limit the harm of anticompetitive activity. At the same time, claims that stricter antitrust enforcement will suppress beneficial conduct are overstated. The before and after lessons of pay-for-delay should be a cautionary tale for courts as they apply antitrust law.