Overview

Six months into a pandemic that is keeping many businesses closed across the United States, and with close to 1 million new unemployment claims continuing to be added each week, there should be widespread agreement that unemployed workers are blameless for their condition. Yet stereotypes that find fault with jobless workers are already appearing amid the coronavirus recession and are an obstacle to economic recovery that threatens to leave lasting scars on unemployed individuals.

The stigma of unemployment is an unfounded bias that views the unemployed as lazy, less-productive workers who are personally defective, worthy of contempt, and to blame for being unemployed. Prejudice against the unemployed hampers the effective delivery of benefits to millions of workers out of a job, leads to hiring discrimination against the unemployed, and can cause long-term damage to workers and the economy.

I and my co-authors Geoff Ho at Rogers Communications Inc., Margaret Shih at the University of California, Los Angeles, Daniel Walters at INSEAD, and Todd Pittinsky at Stonybrook University examined the psychological roots of employer discrimination against the unemployed in the aftermath of the Great Recession of 2007–2009.1 We find that the stigma against unemployed workers operates like other psychological prejudices and biases, is unjustifiable on productivity grounds, and occurs nearly instantaneously to workers losing their jobs.

This issue brief examines these findings in light of the importance of preventing unemployment and mitigating the downside impacts of unemployment, as policymakers address the continuing damage in the U.S. labor market caused by the current coronavirus recession. I will first examine current U.S. unemployment trends and then document how unemployed workers are discriminated against in the job market due to the stigma of being unemployed. This issue brief then details how this discrimination scars unemployed workers for the rest of their careers while sapping U.S. economic growth.

I close with some policy recommendations to address the stigma of unemployment, among them:

- Reforms to the Unemployment Insurance system

- Automatic stabilizers for unemployment benefits that match the distribution of benefits to the state of the economy

- Work-share employment policies

- Direct government jobs programs

In these ways, the stigma of unemployment is overcome by policies that help unemployed workers exit their joblessness as quickly and efficiently as possible to help them and the broader U.S. economy.

U.S. unemployment trends in the coronavirus recession

In July 2020, an unemployed Florida worker who had not received any benefits after 5 months without work said, “Gov. DeSantis, if you hear this, please, please help me get my unemployment. I’m not asking for anything that’s not mine. I’m not a lazy bum. I’ve worked my whole life.”2

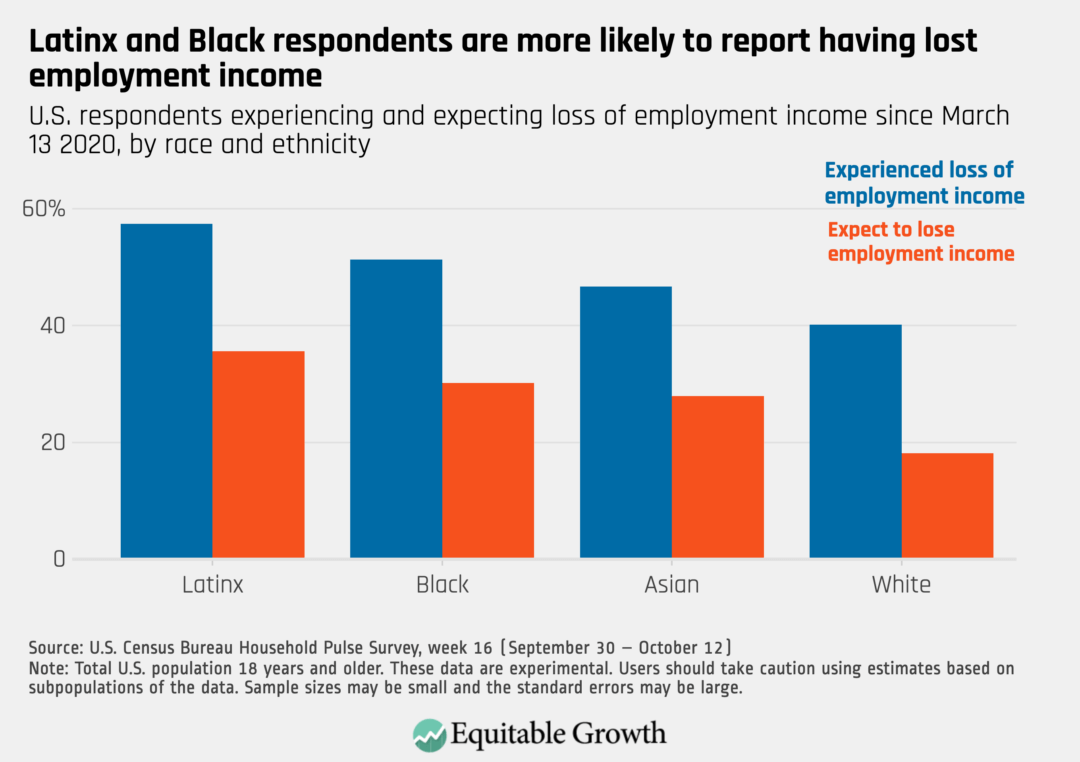

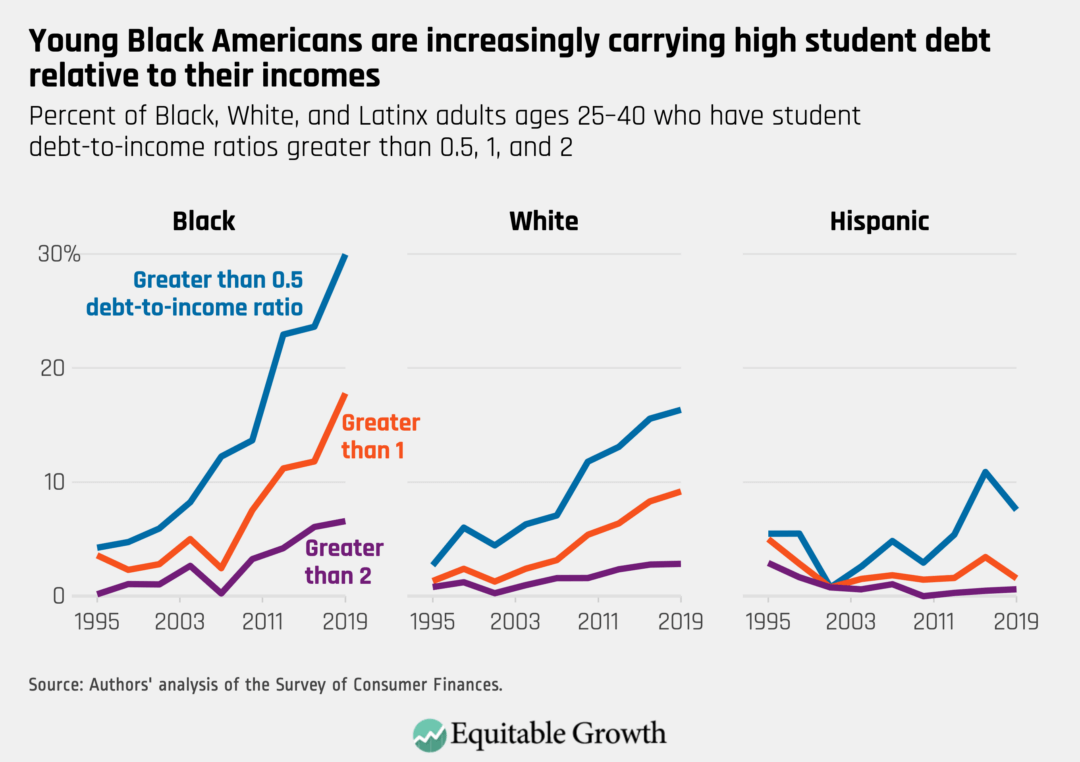

This unemployed worker’s plea is emblematic of the stigma associated with being unemployed and the challenges facing a growing number of unemployed workers. Unemployment trends suggest that a lack of work is particularly likely to affect Black workers and women workers. Evidence suggests that rates of job displacement in economic downturns are discriminatory, meaning that Black workers are more likely to be laid off, all else equal, greater than what can be explained by differences in the types of sectors and jobs where Black workers are overrepresented or years of work experience.3 This contributes to the persistent 2-to-1 Black-White unemployment ratio.4

Workers’ time out of work is not only lost income during that time period, but also leads to diminished future earnings. This dynamic is especially evident among women workers who need to take time off for family caretaking.5 The disadvantage is now exacerbated in this recession alongside the public health crisis that has increased family care needs. Research on differences in outcomes by generations of Americans amid the Great Recession shows that often, the groups hit the hardest by unemployment in a downturn will take the longest to recover jobs and their earnings—even once the economy is technically in an expansion.6

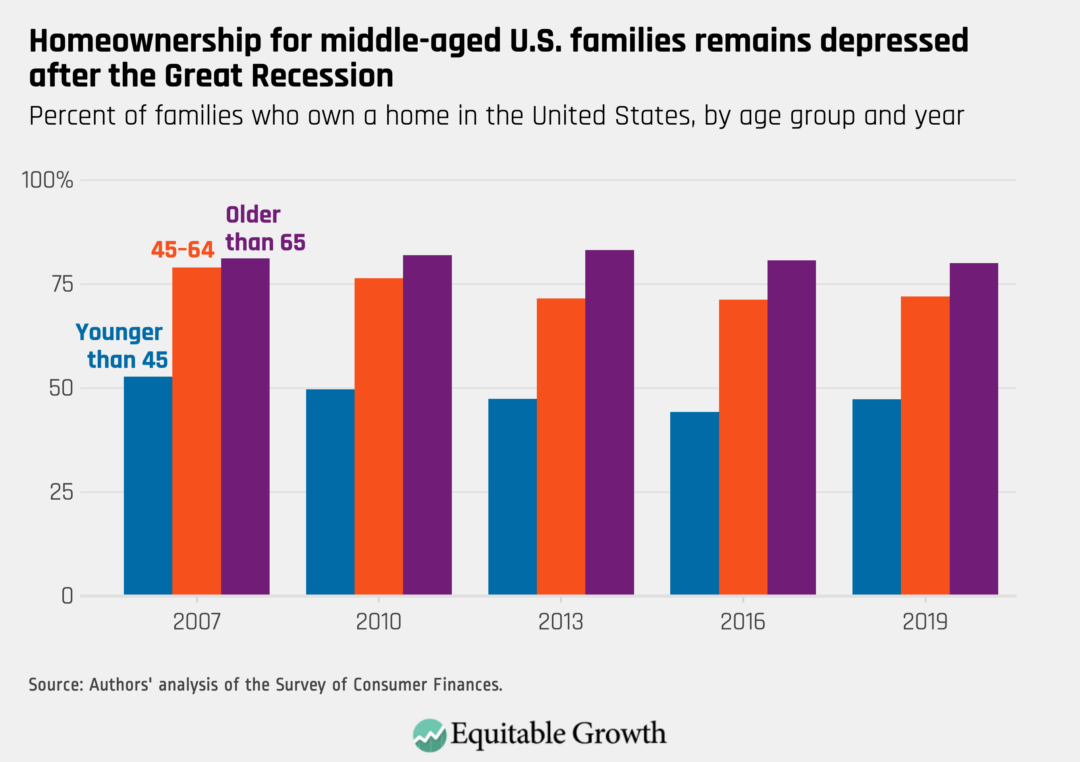

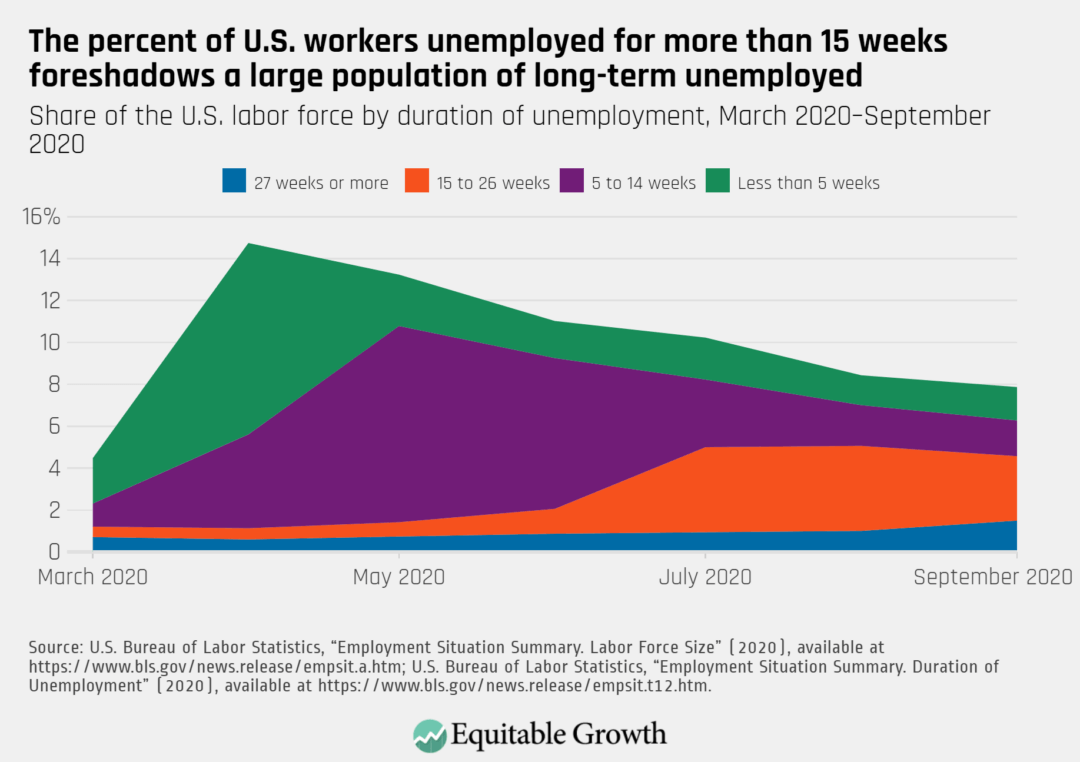

Today, the first waves of those unemployed due to the coronavirus recession are about to enter long-term unemployment, defined as being unemployed for more than 26 weeks. Almost 800,000 workers first laid off in March entered long-term unemployment in the month of September. As of September, 4.6 percent of the U.S. labor force, or 58 percent of the unemployed—7.3 million workers—are now unemployed for more than 15 weeks. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

For the 2.4 million long-term unemployed workers in September, and for the overall health of the U.S. economy, addressing the stigmatization of unemployment is a major challenge now and will remain so in the years ahead.

The stigma of unemployment

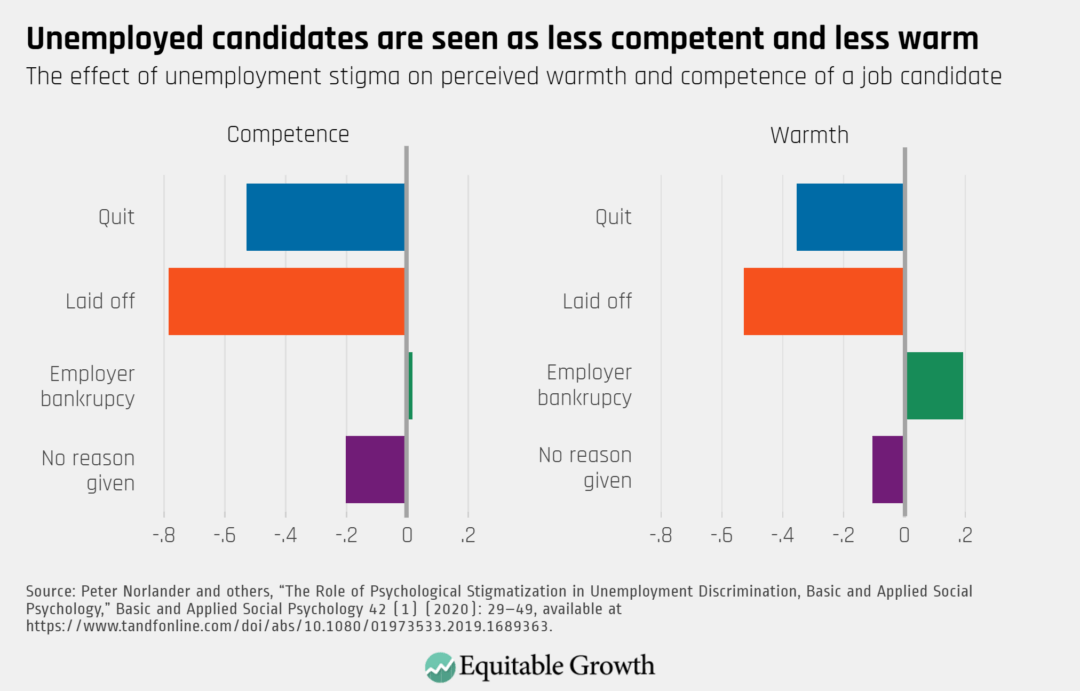

My and my co-authors’ research finds that hiring managers and HR departments often blame unemployed workers for losing their jobs, even when laid off in a severe recession. We presented online and student respondents, as well as real hiring managers and HR professionals, with different reasons for why a fictional job candidate became unemployed, including:

- Lay offs

- Quitting

- Employer bankruptcy

- No reason given

We find that an unemployed job seeker was a target of discrimination, compared to an employed job candidate. Specifically, we conducted five studies that asked participants to evaluate an otherwise-identical resume of a worker who is either unemployed or employed at the time of applying for a job. The results show that the unemployed are evaluated harshly, and not just in terms of their abilities.

Only by emphasizing in the clearest way that the unemployed person was not at fault for being unemployed—by specifying that the unemployed person was out of job because their former employer went out of business—could we reverse the stigma of unemployment that blames the victim. In addition to being seen as less competent, an unemployed job candidate is seen as less warm, less trustworthy, less well-intentioned, less friendly, and less sincere, compared to employed job candidates. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

In the aftermath of the Great Recession of 2007–2009, long-term unemployment persisted at high levels for more than 5 years. It’s obviously too early to tell whether this same trend will play out after the end of this recession, but stigma against the unemployed can harm job candidates even if they are out of work for a short period of time. In a field study that involved sending real resumes to real job advertisements, our study finds that discrimination occurs even when a resume shows that the unemployed person was employed until the prior month. This suggests that the stigma and discrimination against the unemployed is not justified by the theory that firms discriminate against unemployed workers because of skills lost during long durations of unemployment.

Unemployment is one channel through which an individual can be marked by stigma. Research by sociologist David Pedulla at Harvard University shows that members of disadvantaged demographic groups carry stigma even before the experience of unemployment begins and thus face discrimination in the labor market regardless of an employer’s perceptions of their employment status and reason for job separation. Because Black, Latinx, and women workers already have higher unemployment rates than White males and are already subject to high levels of discrimination, there may not be much room for the level of discrimination they face to increase. Indeed, Pedulla finds that the level of stigma increases most for White males, who do not face prejudice based on their demographic group.78

The consequences of stigma

When workers are unemployed for a long period of time, this can lead to long-lasting damage to the psychological well-being and economic future of individuals.9 Joblessness decreases self-esteem, a sense of being in control of one’s destiny, and confidence. At the same time, it increases alienation, anxiety, and depression.10 Some research shows that joblessness may impact Black workers to a greater extent, due to fewer resources available to recover from the downside effects described here.11 As described above, Black workers are laid off more frequently, have higher unemployment rates, and face greater disparities in the coronavirus recession.

In addition, research demonstrates that long-term unemployment leads to:

- Lifetime lower wages12

- A worse quality of life and diminished lifespan13

- Lower odds of being re-hired14

- Increased risk of suicide15

Targeting the unemployed for relief is an essential first step to prevent suffering and speed up an economic recovery. Unemployment Insurance benefits help mitigate the damage of unemployment by lessening wage scars, among other benefits.16 But in addition to this program, and precisely because unemployment is so stigmatized and has such long-lasting damage on individuals and the economy, efforts focused on preventing further unemployment and mitigating long-term unemployment should be at the center of recovery plans.

Policies that would prevent more workers from being stigmatized by more swiftly re-employing the unemployed are described in the following section.

Don’t let unemployment stigma get in the way of economic recovery

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act provided $600 in supplemental weekly jobless benefits, which expired at the end of July. The law also extended unemployment benefits from the usual 26 weeks to 39 weeks, with that extension set to expire on December 31, 2020.17 These benefits are expiring far too soon. Economists estimate that the peak of long-term unemployment in the coronavirus recession will involve 2 million workers who will be unemployed for more than 46 weeks by early 2022.18

Already, conservatives opposed to extending these benefits seek to shift the blame to unemployed workers. Conservative commentators Stephen Moore, Art Laffer, and Steve Forbes argue that benefits for the unemployed discourage work. And Republican Sen. Lindsay Graham (SC), summing up the views of many of his conservative colleagues on Capitol Hill, termed expanded unemployment benefits a “perverse incentive.”19 This argument is based on a stigmatized view of unemployment because it assumes that workers prefer leisure to work (are lazy) and blames the victim (believing that a motivated unemployed person could find a job at any time).

Unfortunately, many unemployed U.S. workers are blocked from accessing any of these unemployment benefits due to a stigmatized Unemployment Insurance system that attempts to screen the worthy from the unworthy and is now failing these workers in their moment of crisis. Barriers to accessing unemployment, including confusing eligibility criteria, lack of awareness, and antiquated information technology systems are characteristics of a stigmatized benefits system. Meanwhile, many unemployed workers are waiting weeks to receive benefits for which they were eligible, and many never received any at all.20

The ineffective administration of unemployment benefits also likely is hampering an economic recovery because jobless workers are unable to spend at a critical moment when spending would speed a recovery. Expanding benefits by resuming the $600 weekly supplemental payment and extending benefits for as long as necessary would help. Reforms to the Unemployment Insurance system to hasten the return to full employment could include:

- Increasing the federal taxable wage base and indexing it to inflation to ensure adequate funding

- Designing automatic benefits extensions so that the program can respond quickly to rapid downturns, such as the current recession

- Implementing a minimum benefit level that would incentivize eligible workers to apply to the program21

To counteract unemployment stigma, counteract unemployment

The best step to prevent the harm of unemployment is to prevent people from becoming unemployed. One way to do so is through direct government hiring and incentives for firms to keep people employed and hire the unemployed. Direct payroll subsidies, as in the Paycheck Protection Program, saved jobs but were too short-lived and not generous enough.

Employers in states with work-sharing programs could reduce hours without laying off workers or reducing incomes if these short-time compensation programs run through state Unemployment Insurance systems had wider participation. But short-time compensation is not adopted by enough states and has not been well-targeted toward low-wage workers in particular, despite benefits associated with maintaining a workforce during downturns. In addition, any federal aid for municipalities and states could prioritize maintaining employment levels to prevent further rounds of mass layoffs.

In future stimulus proposals, direct payroll subsidies or job creation tax credits for hiring long-term unemployed workers could be considered as well.22 Such programs would offer incentives to firms that hire unemployed workers, essentially by offering wage subsidies.

By preventing workers from becoming unemployed and hastening the return of the unemployed to work, the above policies can shorten the time to economic recovery. Such actions can also be far cheaper in the long run than having the unemployed remain idle and can prevent the damaging consequences of unemployment stigma.

— Peter Norlander is an assistant professor of management at Loyola University Chicago.