Can policymakers reverse the unequal decline in middle-age U.S. homeownership rates?

Overview

Homeownership in the United States has long functioned as a wealth equalizer, allowing middle-class families to build wealth while they pay for their housing costs. Because houses have generally appreciated at rates that exceed inflation, housing is often an important source of wealth accumulation for low- and middle-income families, which are generally not invested in stocks or other financial investments. In fact, for the middle class (defined here as the middle quintile by income), home equity represents an average of 42 percent of all wealth held by the average family.

The ability of middle-class families to build equity through homeownership historically allowed these families to somewhat keep pace with the growing value of financial investments held by those at the top of the income distribution. Middle-class families generally enter homeownership following key lifecycle events such as getting married and having children. And as they pay off their mortgages and their houses appreciate in value, they steadily accumulate the housing wealth they will need to help support themselves in retirement.

But this pillar of middle-class wealth creation is under threat. The Great Recession of 2007–2009 and the long, tepid recovery that followed it interrupted the standard lifecycle progression of rising homeownership by age for younger generations. The result is that current rates of homeownership are now lower than they were for older generations at comparable ages.

In addition, total housing wealth in the United States continues to be depressed relative to the period prior to the Great Recession. Last week’s release of the Federal Reserve’s 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances shows that inflation-adjusted housing wealth declined 13 percent between 2007 and 2019.

In this issue brief, we focus on families with middle-aged heads of households. These families have suffered a persistent decline in homeownership just as they are preparing for retirement, when owning a house provides an important source of financial security. These families are at risk, and policymakers should act to make homeownership more accessible to them and all Americans. Restructuring mortgages to take account of macroeconomic shocks and changing tax incentives for homeownership are two ways we can tackle the problem.

Why focus on families with middle-aged heads of households?

Economic narratives often focus on declining homeownership for the youngest generations entering the workforce. This is because buying a house is seen as a foundational step toward financial security. The drop in homeownership at young ages is concerning, and economic forces such as reduced earnings prospects and higher student debt burdens may be limiting homeownership for millennials.

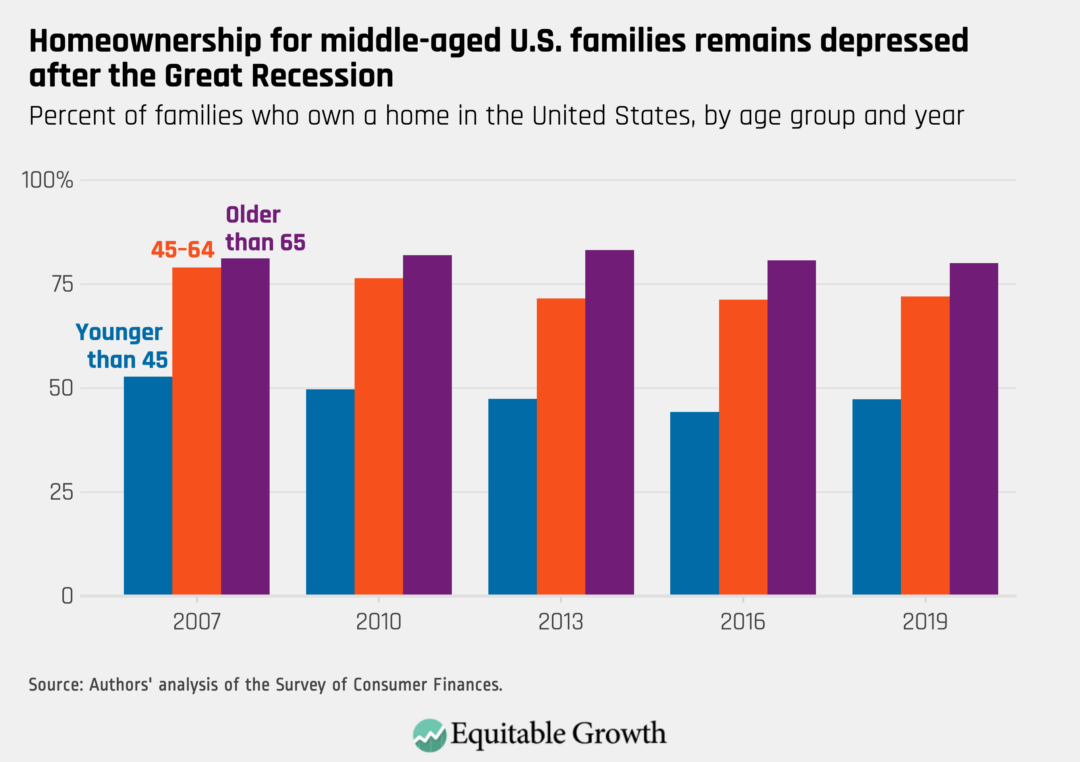

Yet some of the long-run decline in homeownership among the youngest families is the result of delayed entry into homeownership because of demographic factors such as declining marriage rates and fewer children. Indeed, 2019 SCF data show a small uptick in homeownership among young families between 2016 and 2019—defined here to include those younger than 45—that would be consistent with delaying rather than completely foregoing homeownership. Still, homeownership rates for the young remain below 2007 levels.

The slight improvement in homeownership for the young between 2016 and 2019 does not extend to the middle-age group. The decline in homeownership among middle-aged (ages 45 to 64) families since the Great Recession has been relatively larger and more persistent. In 2007, 79 percent of U.S. families in the middle-age group owned their homes, and in 2019, that fraction was only 72 percent. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The consequences of this dramatic shift in homeownership for middle-aged families are serious. Just as these families are nearing retirement and should be actively preparing for it, many have lost their most important financial asset or find themselves unable to invest in a house for the first time. The upshot: Typical lifecycle wealth accumulation patterns are no longer working in their favor.

The overall decline in homeownership among the middle-age group is 7 percentage points since prior to the Great Recession, meaning nearly 1 in 10 families who would have owned their home going into retirement prior to the Great Recession are now likely to enter retirement as renters. These families will now have to worry about rental-housing costs in addition to the other costs of supporting themselves when they retire and their income declines—and without any home equity to fall back on.

Inequities in middle-aged homeownership

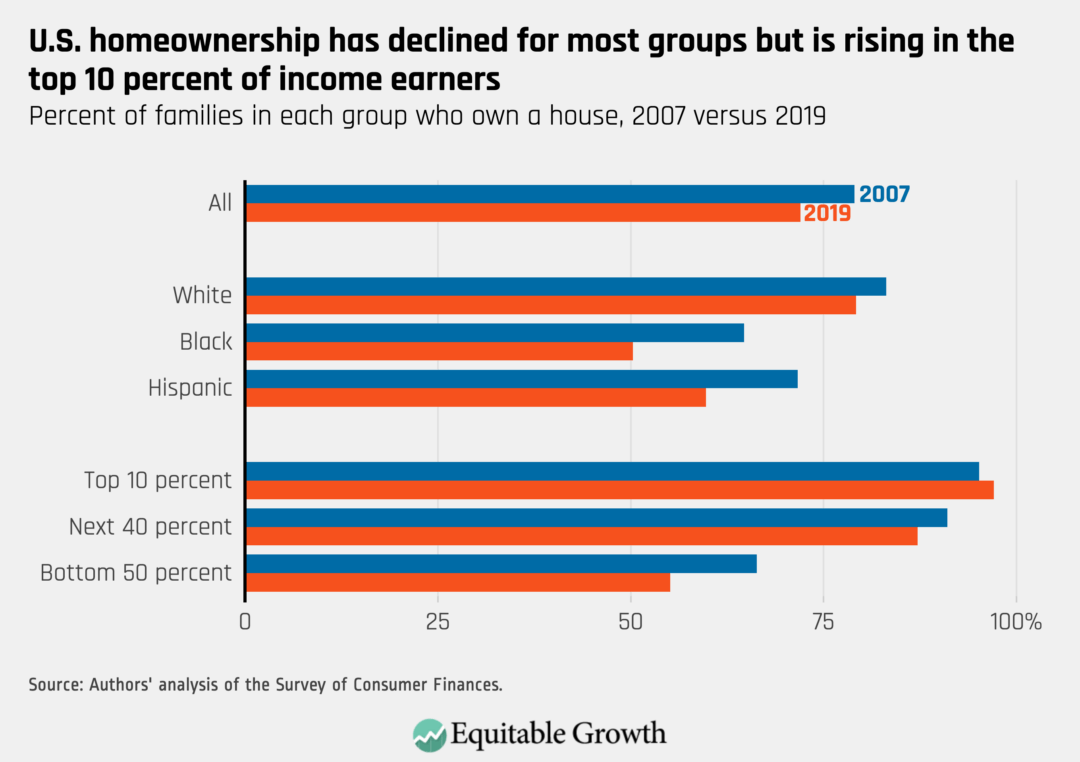

The Fed’s 2019 SCF data release also makes it possible to better understand which families within the middle-age group have experienced declining homeownership since the Great Recession. Unsurprisingly, the decline is greatest for Black and Hispanic families and for those in lower income brackets. In contrast, the top 10 percent of middle-aged families, ranked by income, saw an increase in homeownership between 2007 and 2019. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Homeownership among Black middle-aged families declined a staggering 14 percentage points between 2007 and 2019, while Hispanic middle-aged families experienced an alarming 12 percentage point drop. There was a decline among White non-Hispanic middle-aged families as well, but it was a much more modest 4 percentage point decline and relative to a much larger 2007 base. In 2019, nearly 80 percent of middle-aged White non-Hispanic families owned their homes, while the corresponding values for Black and Hispanic middle-aged families were only 50 percent and 60 percent, respectively.

Differences by income also paint a picture of stark and unequal homeownership rates. The bottom 50 percent of families by income saw an 11 percentage point decline in homeownership between 2007 and 2019, while those in the next 40 percent by income saw a more modest 4 percentage point drop. The top 10 percent of families by income saw an increase in homeownership of 2 percentage points between 2007 and 2019.

On net, the homeownership gap between the top 10 percent and bottom 50 percent of families by income jumped from 29 percentage points in 2007 to 42 percentage points in 2019. Fully 97 percent of middle-aged families in the top 10 percent by income owned their home in 2019, while only 55 percent of middle-aged families in the bottom half of the income distribution were homeowners.

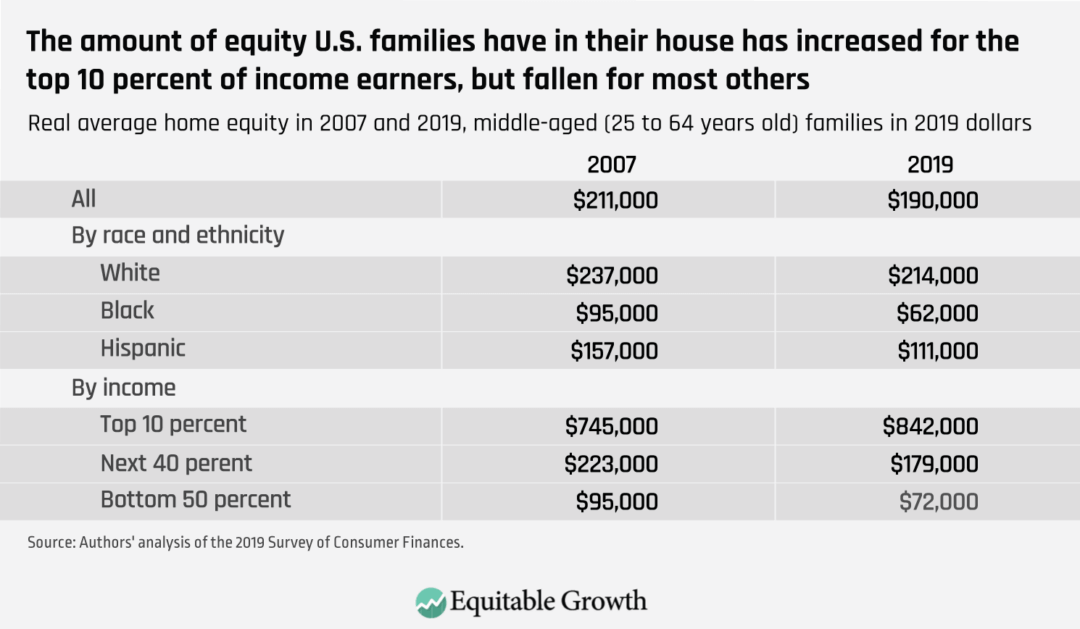

The widening homeownership gap understates the severity of the problem. This is because the amount of equity that families have in their homes also declined. Overall, home equity is down 11 percent, and this decline is inequitably distributed, just as the decline in homeownership is. White families experienced declines in their home equity of about 10 percent, while Black families suffered a staggering 35 percent drop and Hispanic families a 29 percent decline, compared to before the housing crisis in 2007.

As with homeownership, the only place on the income ladder where families are building up their home equity is in the top 10 percent of families by income, where equity is up 13 percent. In the bottom 50 percent of families by income, equity is down 24 percent. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

These drops mean that vulnerable families are less able to take equity out of their homes as a guard against hard times. Given the parlous state of retirement savings in the United States among low- and middle-income families, declining home equity is another kick in the teeth for many families.

Policy prescriptions

These dire trends in homeownership for middle-aged families are both stark and foreboding. Accumulating wealth through homeownership does not happen overnight. Housing appreciation and mortgage repayment is a slow and steady process, and there are generally ups and downs in the housing market along the way. As we contemplate the prospects for changes in U.S. homeownership policy, it is important to delve into the systematic problems that bring us to this point and address those problems directly.

Historically, the focus of U.S. policy toward homeownership allowed tax deductions for mortgage interest. The benefits of those policies are very skewed toward higher-income families, and it’s not clear they even really impact homeownership rates more broadly.

Despite recent legislative changes in the deduction for mortgage interest, the tax benefit of mortgage interest deductibility still cost U.S taxpayers $36.9 billion in Fiscal Year 2020 ending September 30, 2020. That number is just $10 billion less than what the administration requested to fund all of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development for fiscal year 2021.

How might government resources be better-allocated to address inequities in homeownership? One possibility is to directly expand the supply of affordable housing and assist those currently shut out from access to homeownership so they can start investing their rental payments in their own wealth accumulation. Such a policy might be accompanied by redirecting other forms of housing assistance into owning homes rather than renting them. One way could be through repurposing Department of Housing and Urban Development Section 8 vouchers, which provide rent support to low-income households.

Taking an even broader perspective, however, it may be time to recognize that the mortgages predominantly used in U.S. housing finance—and explicitly promoted by the federal government—place an undue amount of risk on families who own their homes. The question is not whether lower-income and disadvantaged families have the resources during normal times to pay monthly housing costs—most of those families do pay those costs, just in the form of rent. The question is what happens to their ability to pay for housing when they experience a large macroeconomic shock.

It is well-known that macroeconomic shocks such as the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and the current coronavirus recession cause disproportionate job and income losses among lower-income and non-White families. The higher income volatility these families face makes it more difficult for them to qualify for a mortgage, especially under the tighter standards in place since the Great Recession. And even if a family manages to enter homeownership prior to the next macroeconomic shock, they are more likely to fall behind on payments and lose their home when the next shock occurs.

This reinforcing dynamic of higher vulnerability to macroeconomic shocks leading to lower homeownership and wealth accumulation should be the starting point for new policies to address rising inequities in homeownership among middle-aged families. The existing U.S. regulatory environment focuses on whether a family can be expected to have the steady income stream needed to keep up with mortgage payments should another macroeconomic shock occur. But that approach is backwards.

Instead, policymakers should develop new approaches to managing employment and income risk so that prospective homeowners among families who currently face barriers to homeownership can safely buy homes. Policymakers should enable the most vulnerable to become homeowners rather than simply accepting unequal employment and income risk and using that to justify stringent mortgage requirements.

Recognizing that macroeconomic shocks are more likely to harm families financially—particularly those historically excluded from homeownership—should be the basis for new policies that directly address the dynamic of steady employment and wealth accumulation. Policies can and should tie mortgage payment obligations to macroeconomic shocks, so that banks and prospective homeowners can enter mortgage contracts with confidence, knowing that the terms of those contracts are explicitly tied to economic realities.

The CARES Act passed in March 2020 provided the option of forebearance to homeowners experiencing pandemic-related economic hardship, but many families are still needlessly delinquent. This underscores the need to automatically connect government policy to macroeconomic reality, and homeowner relief is an important addition to the list of automatic stabilizers that should be in place to help prevent economic shocks from becoming worse.

Although the overall financial situation of homeowners is less perilous than before the financial crisis, some of that improvement is because the families facing the most uncertain finances have been excluded from homeownership. Even so, many families continue to face the risk of losing their homes, and there is still more to be done, for example, by streamlining refinancing and providing immediate payment relief.

But even more important is implementing policy changes focused on the group of middle-aged, would-be homeowners—the additional 7 percent of middle-aged families who would have owned homes in 2007 but are renting in 2019. Tying effective homeowner relief policies to macroeconomic reality means that potential buyers and lenders can enter into mortgage contracts with confidence, and policymakers can focus on raising rates of homeownership without creating unmanageable risk.

Failure to improve homeownership policy means accepting that many middle-aged families will continue to be shut out of the housing market as they draw closer and closer to retirement. Unless policymakers act soon, the U.S. economy can expect many more struggling retirees in the years and decades ahead.