Research consistently demonstrates that unions across the United States promote the enforcement of labor protections, increase pay for both union and nonunion members, and reduce income inequality. Importantly, labor organizations also help to institutionalize norms of fairness and equity and narrow pay divides along the lines of race and gender.

Amid this year’s Labor Day celebrations, a closer look is warranted at how unions can promote interracial solidarity. One telling outcome is that unionization also reduces racial animus among union members and highlights why increasing the bargaining power of all U.S. workers is key to creating a more equitable economy and a society better equipped to deal with institutional racism at work and in our communities.

In a 2021 paper, Paul Frymer at Princeton University and Jacob Grumbach at the University of Washington propose that in addition to upholding labor standards, boosting wages, and putting the brakes on economic inequality, unions temper racial resentment and foster support for public policies that benefit Black workers, families, and communities.

In their study, Frymer and Grumbach examine the relationship between falling union membership and rising White identity politics. The two political scientists develop a theory in which unions promote support for racial inclusion and equality by influencing the attitudes of their White members.

Indeed, the authors find that union membership not only reduces racial resentment but also results in White unionized workers becoming more likely to support affirmative action and government efforts to improve the social and economic standing of the Black community, compared to their nonunionized counterparts. As such, the steady decline in union membership rates since the late 1950s reflects the weakening of an institution that improves workers’ labor market outcomes and fosters support for civil rights and a stable democracy through its effect on White workers’ attitudes toward race.

An array of complementary research supports their conclusions.

How unions influence political views and attitudes toward race

The power of unions has declined since the height of the labor movement in the mid-20th century, yet unions continue to play an important role both in promoting redistributive policies and in influencing the political views of their members. For one, labor unions are some of the largest civic organizations in the United States and currently represent 14.3 million workers—almost 11 percent of all U.S. wage and salary workers.

Moreover, as sites of democratic deliberation, political mobilization, and information sharing, unions can influence the policy landscape. Research finds, for example, that states with stronger unions tend to have more progressive tax codes and to spend more on public education and on their income support infrastructure.

In the case of attitudes toward race, over the past few decades, unions have had increasing ideological and strategic interests in fostering interracial solidarity. Bruce Western at Columbia University and Jake Rosenfeld at Washington University in Saint Louis call unions “pillars of the moral economy in modern labor markets.” As such, organized labor can be an important advocate for racial egalitarianism by promoting norms of equity, social solidarity, and advancing the interests of low-wage workers both inside and outside the workplace.

In addition, the U.S. labor movement has become more diverse in terms of its racial, ethnic, and gender composition at least since the early 1980s. This means union leaders have incentives to be inclusive of—and responsive to—the interests of workers of color in order to grow their organizations, secure union election victories, and successfully negotiate collective bargaining agreements.

Frymer and Grumbach primarily use two strategies to examine the relationship between union membership and racial resentment. Using data from the Cooperative Congressional Election Study’s Common Content—which is conducted twice a year during election years and contains a sample of about 30,000 respondents—they analyze differences in attitudes toward race. They find that among otherwise-similar White workers—that is, accounting for factors such as age, level of educational attainment, income, and gender—those who are unionized are less racially resentful and report greater support for affirmative action than those who are not.

To further tease out whether unions have an effect on racial attitudes or whether White workers who are more likely to value racial equity self-select into unions, the authors use data from the Voter Study Group—which surveyed the same 8,000 respondents during the 2012 election cycle and then again during the 2016 election cycle—to follow the evolution of their racial attitudes over time. Consistent with the former findings, the authors find that becoming a union member substantially reduced racial animus among White workers.

In addition, they find that union membership is also associated with greater support for government action that advances the social and economic position of the Black community and promotes fair treatment when it comes to hiring.

Labor unions have a complicated history of both racism and racial solidarity

The history of the labor movement is certainly not without instances of systemic racism. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Frymer and Grumbach note, unions regularly engaged in discriminatory practices, pushed back against integration, and even mobilized in support of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882—a restrictive and racist policy which suspended the immigration of Chinese workers and was the first law in U.S. history to ban a group of people on the basis of their race or nationality. Even when not outright segregationist, unions—and craft unions in particular—could be hostile to the enforcement of anti-discrimination measures.

Union leaders have made alliances with civil rights organizations since the advent of the New Deal in the 1930s, and many labor organizations have been proactive in fostering racial equity and advancing the economic standing of Black workers during the Civil Rights era and since then. But others continued to engage in discriminatory practices, were reluctant to integrate, crowded Black workers into lower-paying jobs, and pushed back against affirmative action policies even in the post-Civil Rights era of the late 1960s and 1970s up to today.

As such, Frymer and Grumbach point out that their “theory is contextually and institutionally bounded.” In other words, the observed negative relationship between union membership and racial resentment needs to be understood as specific to the current context—one in which labor unions have egalitarian convictions and strategic incentives to foster interracial solidarity. Likewise, the implications of these findings are especially important in the context of the rising nationalism and racism many nations are facing today.

A strong labor movement today can promote social well-being and broadly shared economic growth

Unions not only play an important role in improving the labor market outcomes of their members and serve as a mechanism to help achieve a more dynamic and inclusive economy, but also act as a buffer against White identity politics. A strong labor movement today can therefore push back against racism and longstanding trends of rising income inequality—both of which can be deeply destabilizing for an interracial democracy. While the authors do not test this hypothesis empirically, they argue that the same mechanisms that temper racial resentment toward the Black community are also likely to reduce White union members’ resentment against immigrants and other marginalized groups.

In finding that union membership reduces racial resentment, Frymer and Grumbach’s research highlights one of the most compelling benefits of promoting workers’ bargaining power, as well as the importance of making it easier for more workers to join and form unions through policies such as the Protecting Right to Organize, or PRO, Act. Research demonstrates that bargaining power is a critical component of reducing income inequality and ensuring that U.S. workers receive income equal to the value they create. In this way, worker power actually helps achieve efficient outcomes like those that would exist in a dynamic and competitive economy.

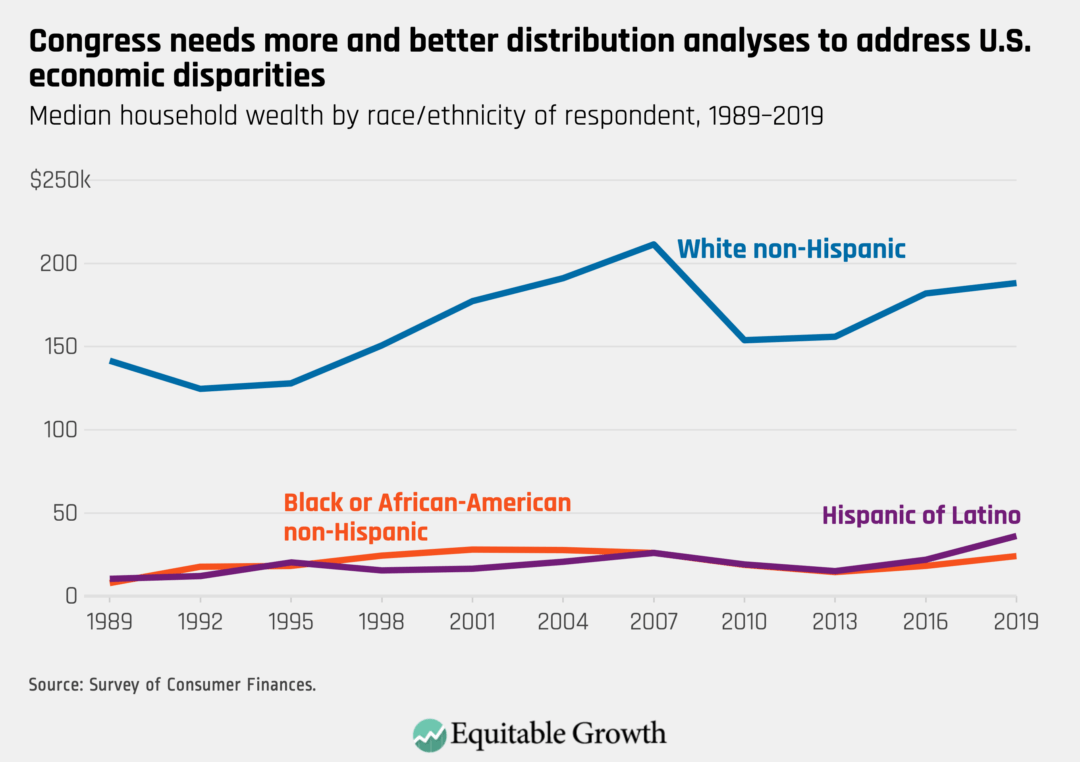

Black workers tend to face persistent wage disparities, and those lower earnings reflect centuries of structural racism. That’s why exercising power at work is core to being paid fairly. Giving workers more tools to exercise their voice at work, promoting policies and political attitudes that advance racial equality, and balancing power in the U.S. labor market would ensure that the economic growth is more broadly shared.