This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

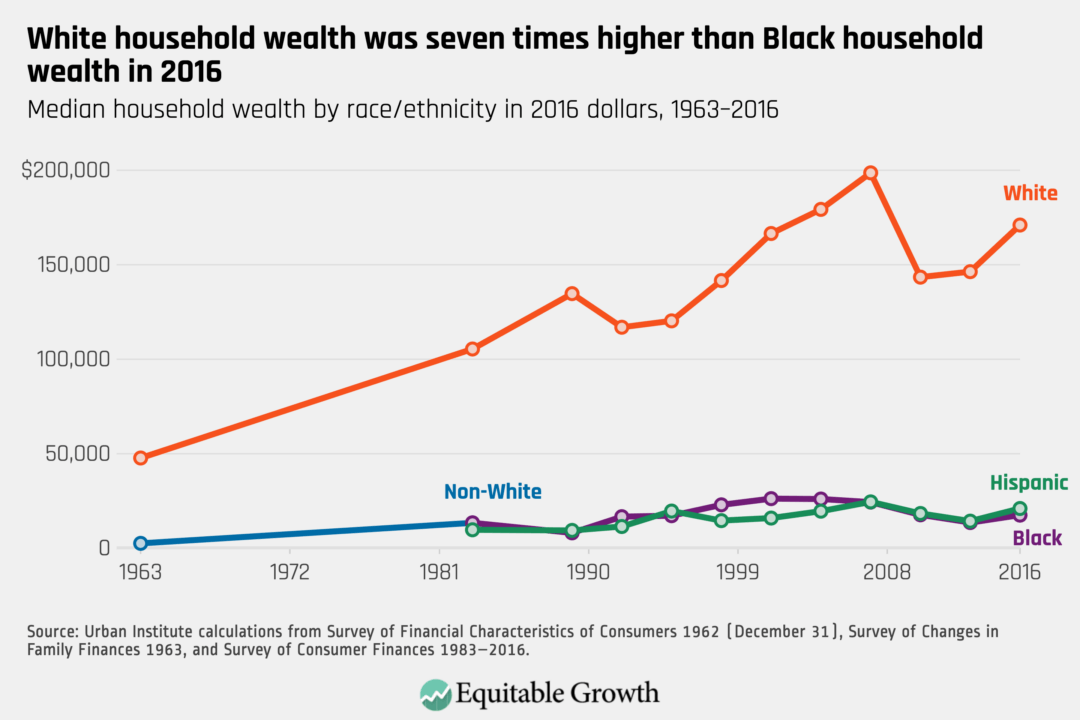

As David Mitchell writes, the American Jobs Plan and the American Families Plan, described this week by President Joe Biden in his address to Congress, would make large-scale, and in some cases permanent, investments in the nation’s physical and human infrastructure. These measures would combat racial, income, and wealth inequality, and they would restructure large parts of the U.S. economy to strengthen and broaden economic growth, combat climate change, and build a lasting and effective care infrastructure. Mitchell summarizes the research that has helped to lay the foundation for the size, the scope, and many of the specifics, of Biden’s policy and programmatic proposals. Our hope, he writes, “is that policymakers follow the compilation of academic evidence that Equitable Growth and others have assembled and capitalize on this opportunity to make structural economic change that spurs strong, stable, and broad-based growth.”

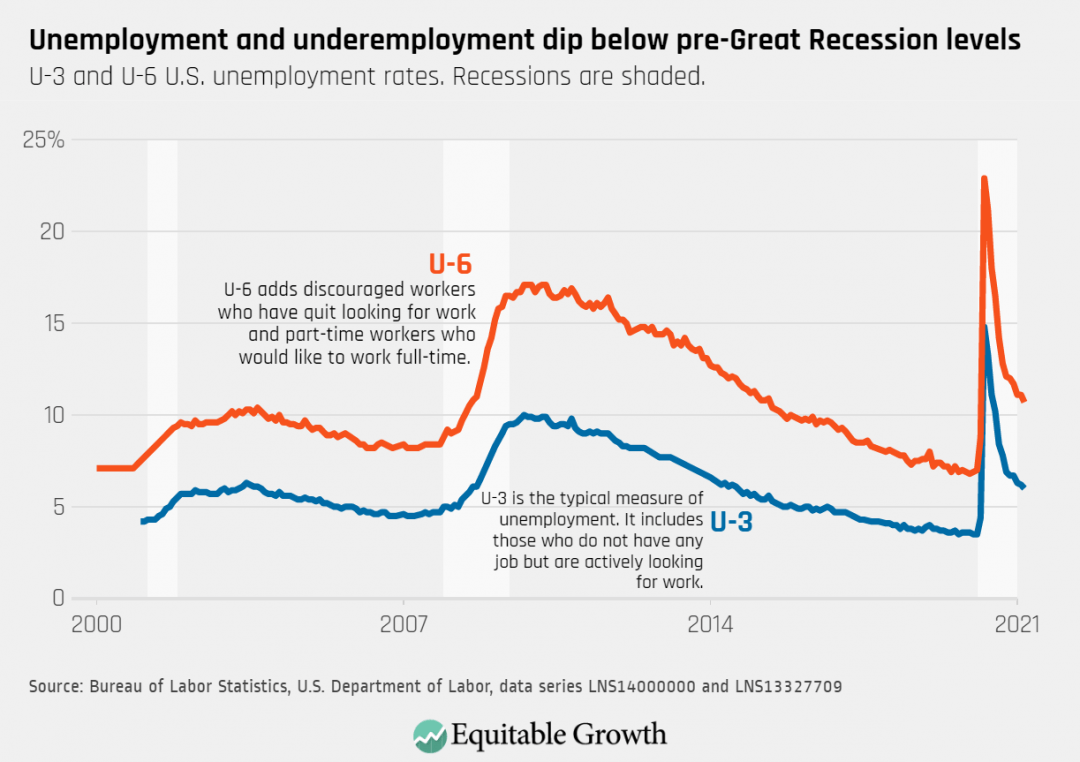

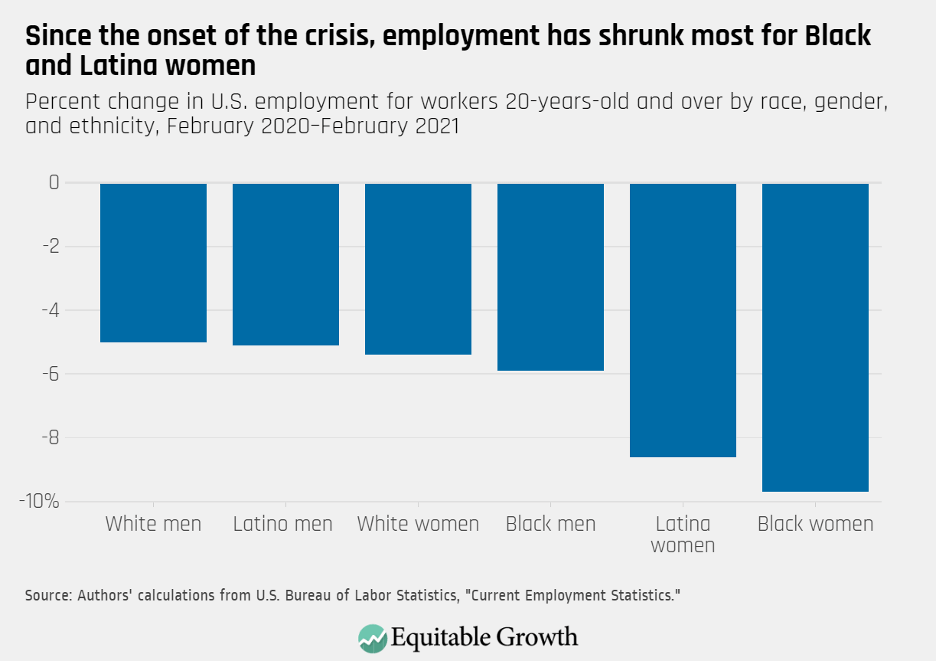

As Congress debates whether those plans, along with the major COVID-19 relief plan enacted in March, are too big, too small, or just right, a new Equitable Growth factsheet addresses an important question: Could these measures, designed to bring about a strong recovery now and lay a foundation for strong and broadly shared long-term growth, send the economy into overdrive, leading to destructive inflation and high interest rates? The title of the factsheet provides the answer: “Overheating is not a concern for the U.S. economy.” The most salient evidence, the factsheet points out, is that the U.S. economy still has 10 million fewer jobs today than it likely would absent the coronavirus pandemic and resulting recession. While it does not rule out the possibility of overheating at some point, the factsheet suggests that it is unlikely in the near term, and that overheating can be addressed if and when it occurs. It concludes that the “general macroeconomic benefits—such as long-term employment gains and fully recovered labor force participation among women and workers of color—significantly outweigh any concern for possible overheating.”

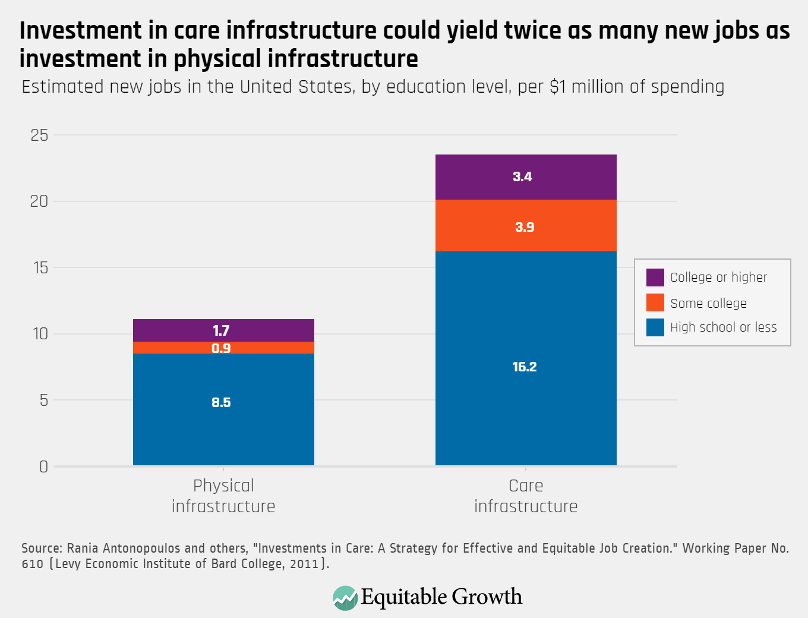

The United States is rare among developed countries in its lack of federally mandated access to child care and early childhood programs and paid family and medical leave, and its weaknesses in long-term and elder care are also well-known. For these reasons, our nation’s care infrastructure is central to the current debate over the size and role of the federal government. The U.S. care economy is the topic of April’s Expert Focus, a monthly feature in which Equitable Growth highlights scholars, both in and beyond our network, who are at the frontier of social science research. The researchers about whom Christian Edlagan, Maria Monroe, and Emilie Openchowski write this month are examining care infrastructure and policies and their impacts on workers, their families, and their communities. The evidence points to longstanding challenges and deficiencies that predate the coronavirus pandemic, which has, our authors write, “only served to deepen these cracks in care infrastructure, particularly along gender and racial lines.”

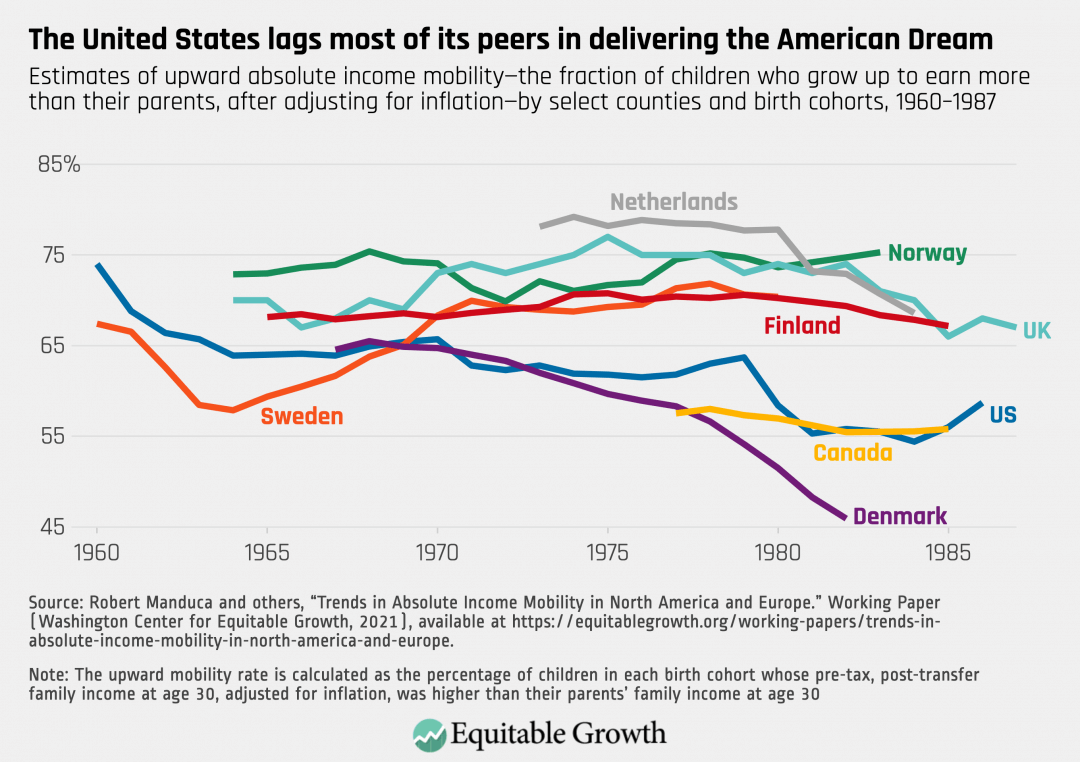

The American Dream of intergenerational mobility—the hope that one’s children will have a better life than one’s own—is more alive in many other countries than in the United States. More than 90 percent of U.S. children born in 1940 had higher real incomes at age 30 than their parents did, but only about 50 percent of children born in 1980 can say the same, writes Robert Manduca of the University of Michigan. Manduca describes a new working paper he wrote with 13 U.S. and European co-authors that examines the question: Was this decline in upward mobility part of a global trend or unique to the United States? The answer, clearly illustrated below in this week’s Friday figure, is that several of the European countries the group studied have maintained high levels of intergenerational mobility, while the United States, along with Canada and Denmark, has declined. He attributes this to the fact that incomes for young adults in these three countries have fallen behind overall economic growth and, in this country, “shifts in the U.S. labor market that advantage employers at the expense of workers are a fundamental cause.”

Equitable Growth’s academic program awards research grants to scholars, mainly at U.S. universities and colleges, seeking evidence on issues related to the intersections between economic inequality and economic growth and stability. Since the organization’s founding in 2013, it has invested more than $6 million in the work of more than 200 grantees. In its second annual comprehensive academic research report, Equitable Growth describes the impact of its funded research, updating what we’ve learned and the questions we seek to answer. It’s an indispensable tool for understanding the organization’s mission and the extraordinary research that has provided evidence that underlies many of the groundbreaking proposals that have become central to the national policy debate.

Links from around the web

Lower-skilled workers suffered the most in the coronavirus recession. And Heather Long reports in The Washington Post that they are the slowest to regain employment as the economy recovers. Hiring has rebounded quickly for those with college educations, including two-year degrees, she writes, but for those with high school degrees or less, jobs are hard to come by, even as the economy begins to reopen and some employers say they are unable to find workers. She said the current economy looks like a “two-track recovery,” with some similarities to the recovery from the Great Recession a decade ago, when workers without college degrees struggled to find employment.

The economic narrative—our common understanding about what makes the economy grow and what it means to be a thriving nation—is fundamentally changing. So writes Chris Hughes, co-chair of the Economic Security Project, in Time. The economic ideology that has underpinned much of the nation’s economic policy since the 1980’s, based on the “myth … that markets, unfettered and free, are the best way to create economic growth,” was discredited during the Great Recession over a decade ago and has “collapsed” in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic and recession. What is replacing that narrative for Americans across the political divide, Hughes writes, is a “managed market paradigm.” As he describes it, “There are three key pillars to a new, managed market approach: effective regulation, sizable public investment, and careful macroeconomic supervision. A managed market requires centralized, accountable institutions embracing their power to create stable and competitive markets where innovation can flourish and labor shares in the wealth.”

As the country begins to come to grips with the fact that communities of color are far more exposed to environmental threats than White communities, a new study, conducted at five universities, shows that even a significant U.S. policy success of recent decades has had considerably less positive impact on Black, Latinx, and Asian American communities. As Juliet Eilperin and Darryl Fears report in The Washington Post, while the country has made great progress in reducing air pollution from fine-particle matter, such as soot, that comes from cars, trucks, factories, and elsewhere, nearly every source of “the nation’s most pervasive and deadly air pollutant still disproportionately affects Americans of color, regardless of their state or income level … The analysis … shows how decisions made decades ago about where to build highways and industrial plants continue to harm the health of Black, Latino and Asian Americans today.”

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s The American Dream is less of a reality today in the United States, compared to other peer nations.