Latino workers represent a large and growing share of the U.S. workforce. But even with the highest employment rates in the United States, Latinos face a number of barriers to accessing good jobs and economic security. Their median earnings are lower than those of their Black, White, and Asian American counterparts. And along with Black workers, Latino workers tend to be especially vulnerable to losing their jobs amid economic contractions.

What’s more, insufficient bargaining power, gaps in legal protections, discrimination, and social norms all can cluster Latino workers into jobs that pay low wages, offer little in terms of employer-sponsored benefits, and rank high in labor law violations. Unions and labor organizers, however, have long pushed back against these obstacles, delivering important gains for both Latino and non-Latino workers.

In the mid-20th century, for example, the late union activist Emma Tenayuca fought for fair wages, advocated for workers’ right to unionize, and led what continues to be one of the largest strikes in U.S. history. In the early 1960s, civil rights activists and organizers Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez co-founded what is now the United Farm Workers. As one of the first and longest-lasting farmworkers unions in the country, the UFW played an important role in securing better working conditions in the agricultural sector—in which Latinos disproportionately are employed—including regulations that protect workers against the harms of heat and pesticides.

Then, between the late 1980s and early 2000s, the Justice for Janitors movement achieved better pay, greater access to benefits, and union contracts for many of these workers at a time when domestic outsourcing began to greatly deteriorate job quality in janitorial services. Janitorial services is an occupation in which Latinos represent almost a third of the overall workforce.

More recently, through both worker organizing and policymaking efforts, Chief Officer of the California Labor Federation Lorena Gonzalez Fletcher helped secure overtime protections for farmworkers and improve labor standards for fast-food workers in California. And in the past few years, unions maintained wages and protected workers against job loss as the COVID-19 crisis launched the economy U.S. economy into a recession.

Indeed, a report by the Latino Policy and Politics Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles finds that workers covered by unions were less likely to experience unemployment during the height of the pandemic. This protective effect, the report finds, was particularly strong for unionized Latinos.

This column examines some of the employment characteristics that determine whether a job is high or low quality, how occupational segregation can sort Latino men and Latina women into jobs with poor working conditions, and how greater worker bargaining power and effective public policy can boost job quality for all workers. While there are many components that go into determining whether a job is good, the focus of this column is on predictable schedules, workplace safety, and minimum wage standards—job characteristics that are not as frequently discussed as pay and access to employer-sponsored benefits but that affect working conditions in many occupations, including those in which Latino workers represent a disproportionately high share of the workforce. Addressing these disparities through greater worker power would go a long way toward narrowing economic inequality in the United States and boosting overall U.S. economic growth.

Right now, Latino workers face several barriers to accessing good jobs

Latino men and Latina women are more occupationally segregated than men and women of any other major ethnic group. In other words, Asian American, Black, and White men are all more likely to work in the same occupation as the women workers of their same racial or ethnic group than Latino men are to work in the same occupation as Latina women.

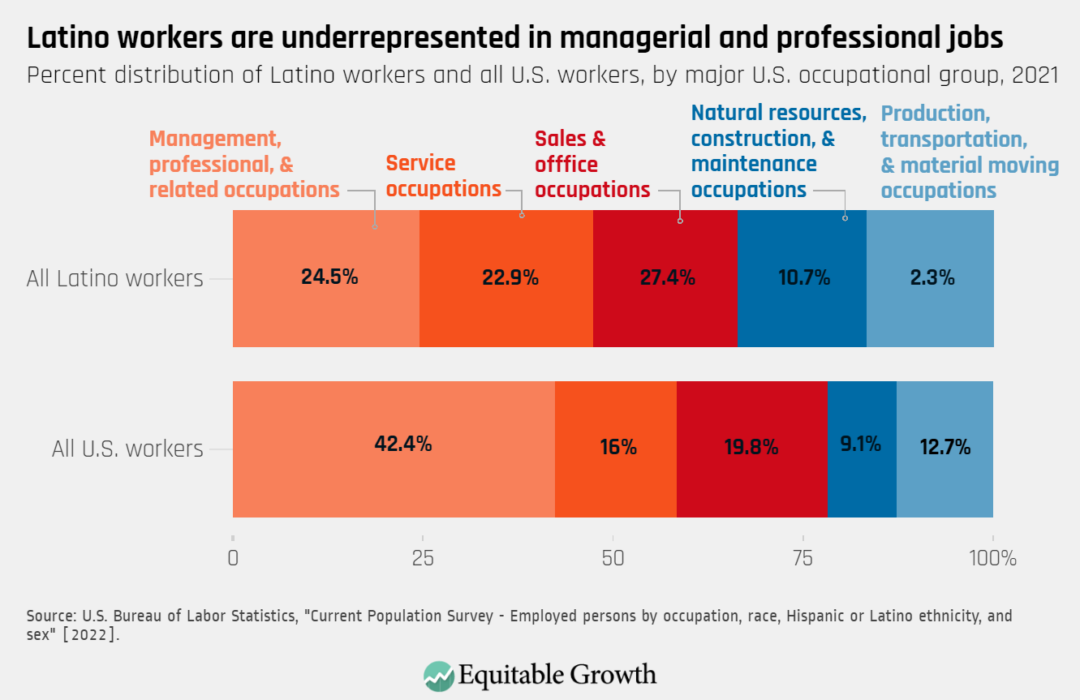

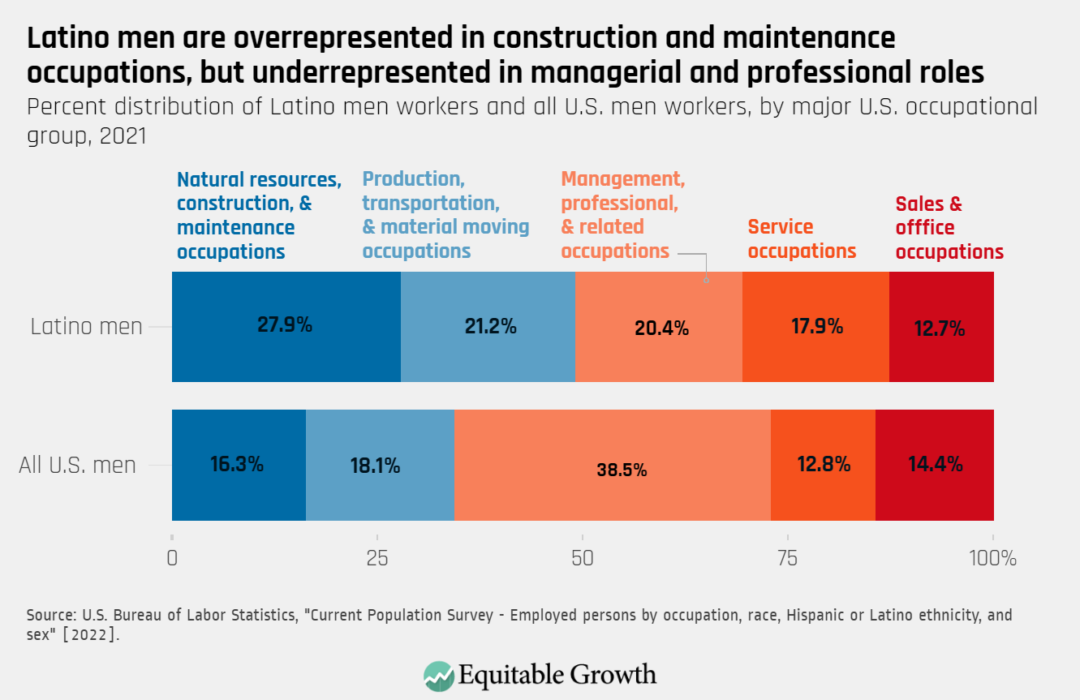

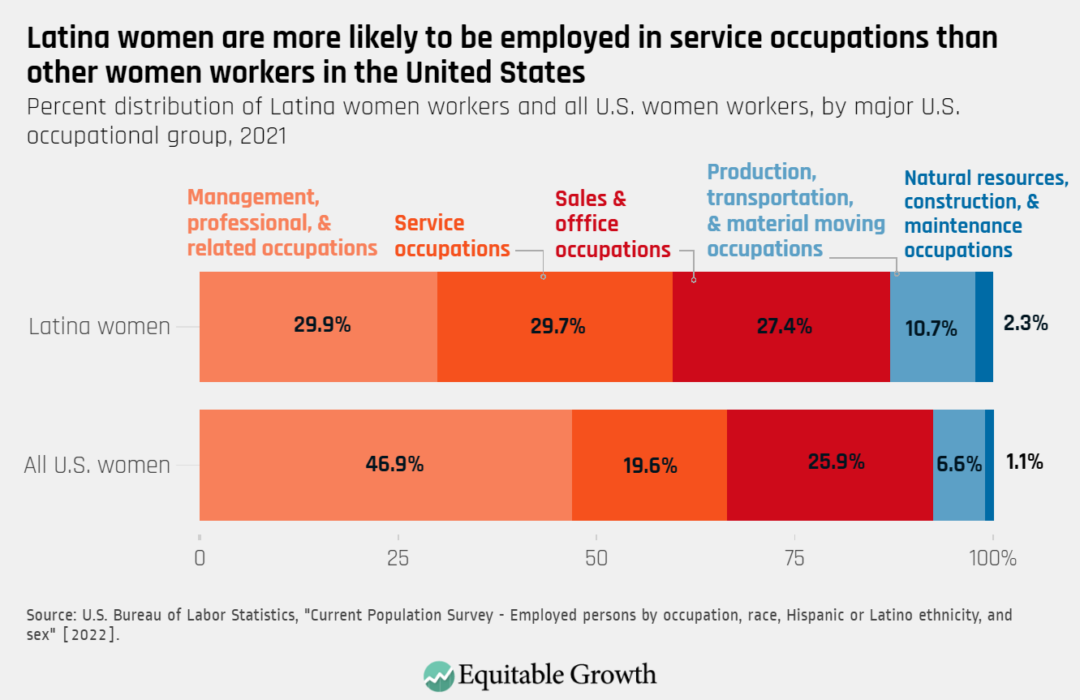

Specifically, occupational segregation results in an overrepresentation of Latino men in natural resources, construction, and maintenance jobs. In contrast, Latina women are overrepresented in service occupations. And both Latino men and Latina women are underrepresented in the highest-paying jobs in management and professional occupations. (See Figures 1, 2 and 3.)

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

But even though Latino men and Latina women are overrepresented in different types of jobs, occupational sorting hurts them in the U.S. labor market. In general, structural and interpersonal discrimination, unequal access to education and training opportunities, cultural norms and expectations, social networks, and hostile working environments all can make some jobs more or less accessible to different groups of workers, resulting in an uneven occupational distribution that exacerbates economic disparities and holds back U.S. economic growth.

For instance, occupational sorting by gender, race, and ethnicity can result in a misallocation of talent by keeping workers from holding jobs that are a good fit for their interests and skills. A team of researchers finds, for example, that as women and Black workers faced fewer barriers to accessing higher-paying jobs after the 1960s, more workers could pursue their competitive advantage, thus boosting aggregate U.S. productivity. They estimate that greater occupational integration thus accounts for about two-fifths of the growth in the country’s Gross Domestic Product per person between 1960 and 2010.

Similarly, there is evidence that women workers’ underrepresentation in engineering, development, and design positions creates a gender innovation gap that, if narrowed, would likely boost U.S. economic growth.

For marginalized groups, occupational segregation does not only mean that already-vulnerable workers are more likely to be clustered into lower-paying jobs. Occupational stratification also leaves some workers especially exposed to economic contractions, explains an important chunk of the stubbornly persistent gender, racial, and ethnic wage divides that exist in the U.S. economy, and entrenches wealth inequality. Occupational segregation also means that some workers are more likely to be exposed to low-quality job traits, such as poor scheduling practices, unsafe working conditions, and labor law violations.

Fair scheduling

Take poor scheduling practices first. When U.S. employers do not provide information about schedules ahead of time, workers have little or no say about when and how long they work, and work hours vary substantially from week to week, making it much more difficult for workers to organize their lives and achieve economic security. Research finds that people working precarious schedules are more likely to experience hunger, struggle to find child care, and experience material hardship. Because low-wage workers, particularly low-wage workers of color, are more likely to experience last-minute shift changes and other bad scheduling practices, low-quality schedules also perpetuate existing economic disparities.

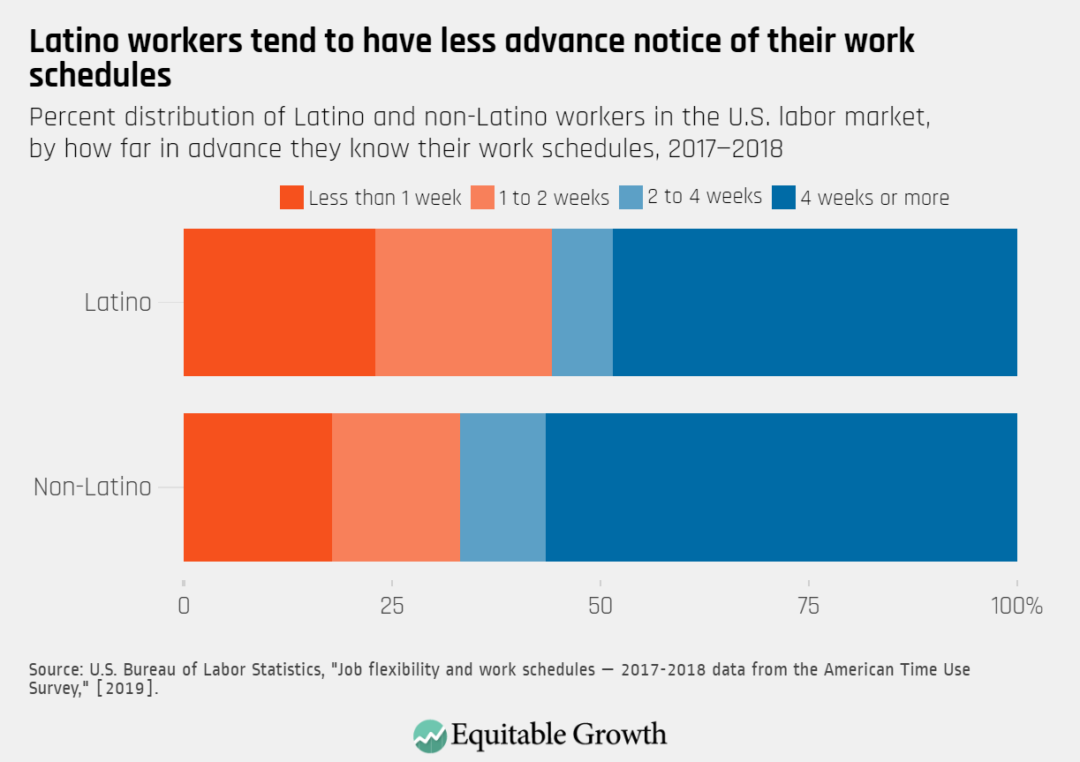

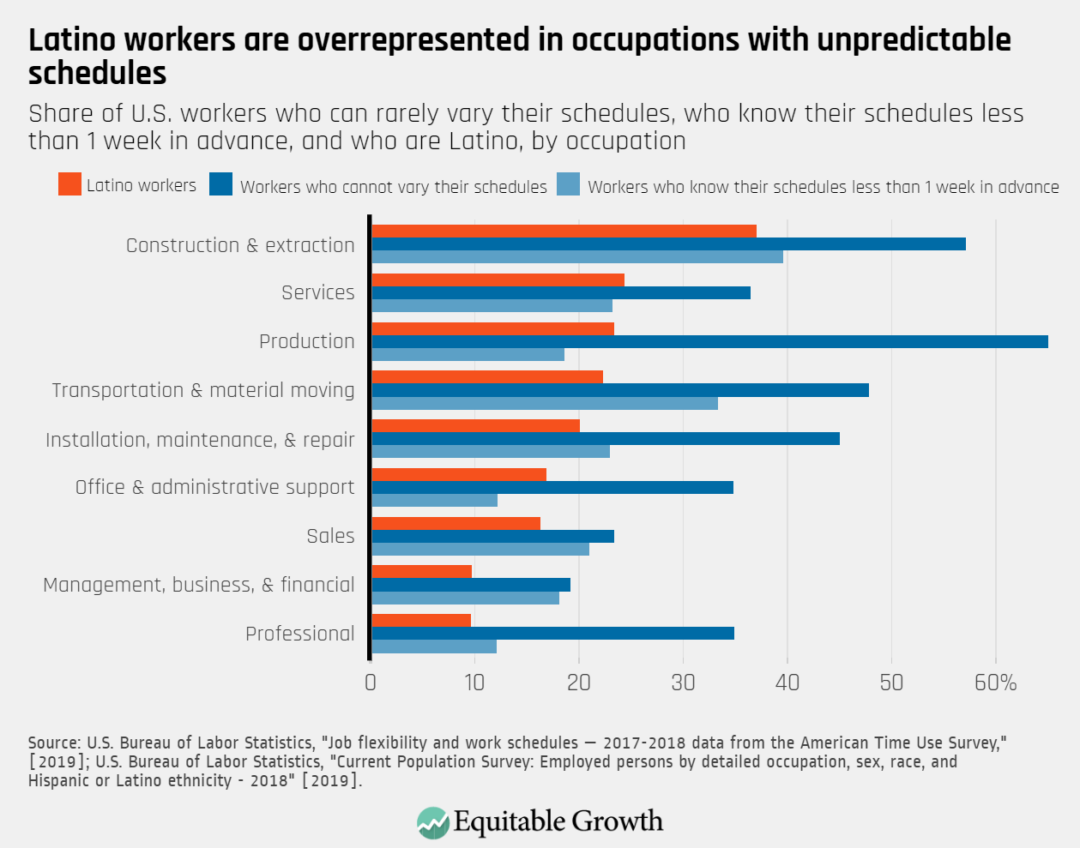

Many Latino workers are exposed to bad schedules. According to data collected between 2017 and 2018 by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Latino workers are much less likely than their non-Latino counterparts to be able to shift their schedules according to their preferences. Further, the same data show that a relatively small share of Latino workers receives information about their schedules ahead of time. The data show that 57 percent of non-Hispanic workers know their work schedules at least 4 weeks in advance, but for Latino workers, that number shrinks to 49 percent. Indeed, almost a quarter of all Latino workers have less than 1 week’s notice about their schedules. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

An important reason why Latino workers are less likely to have good schedules than their non-Latino counterparts is that they are overrepresented in jobs and industries in which problematic scheduling practices are more prevalent. Latinos represent about 18 percent of all workers in the United States. In construction and extraction occupations—jobs in which Latinos represent 39 percent of the overall workforce—almost 40 percent of workers know their schedules with less than 1 week’s notice.

Latino workers also make up a disproportionately high share of workers in some of the occupations that have the most rigid schedules. For instance, Latino workers represent almost 25 percent of all workers in production occupations—jobs in which 65 percent of workers are not able to vary the times they begin or end their workday. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

But research by Adam Storer at the University of California, Berkeley, Daniel Schneider at Harvard University, and Kristen Harknett at the University of California, San Francisco also shows that occupational segregation alone cannot fully explain why Latino workers are more likely to have precarious schedules. In other words, even when employed in the same type of job, Latinos seem to have worse schedules than their White counterparts.

Indeed, using survey data from workers employed in the largest retail or food-service firms in the United States, the team of researchers finds that having a manager of a different race or ethnicity, overrepresentation in firms with poorer scheduling practices, and discrimination also help explain why both Black and Latino workers are especially likely to work unstable and unpredictable hours.

Workplace safety

Workplace safety is one of the most basic components of a good job, yet many workers in the U.S. are exposed to dangerous working conditions. Even before the onset of the COVID-19 crisis in 2020, private-sector employers in 2019 reported 2.8 million injuries and illnesses at work. That same year, there were more than 5,000 fatal work injuries. In 2020, illnesses at work skyrocketed at the same time that injuries dropped, leading to a total of 2.7 million employer-reported nonfatal injuries and illnesses that year.

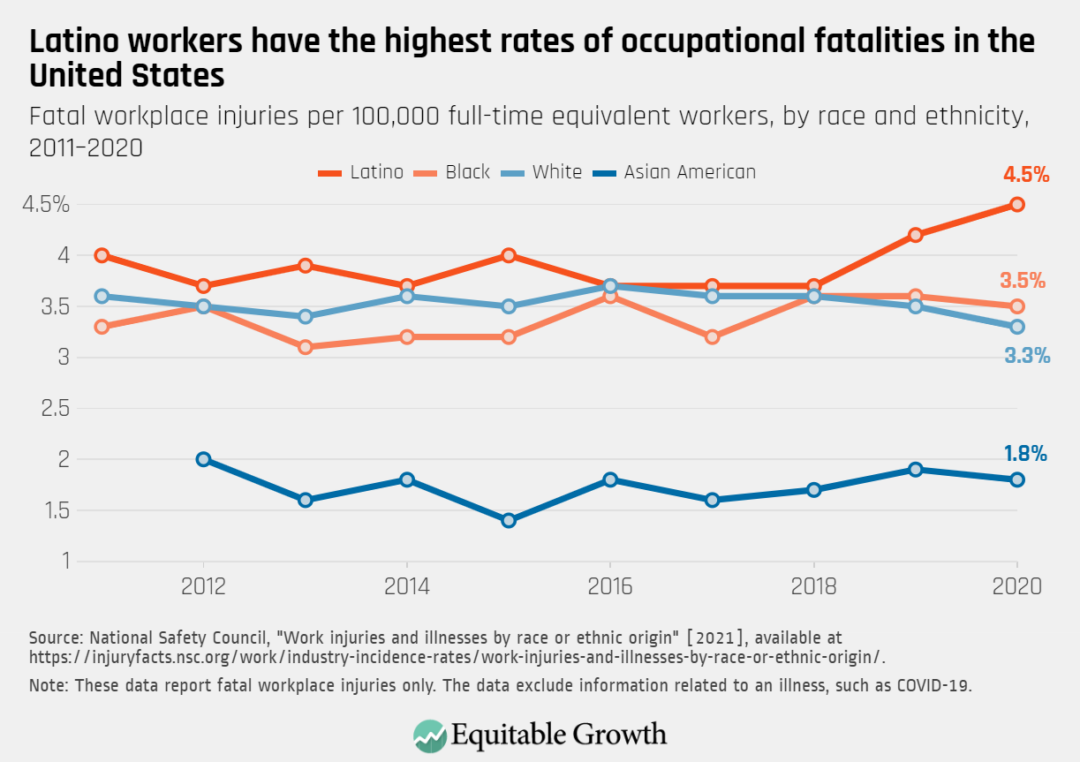

The total number of fatal work injuries did decline during the first year of the pandemic, but for Latinos, the occupational fatality rate actually climbed from 4.2 per 100,000 workers in 2019 to 4.5 per 100,000 workers in 2020. Latino workers thus face the greatest rates of fatal injuries at work, followed by Black workers, White workers, and Asian American workers. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

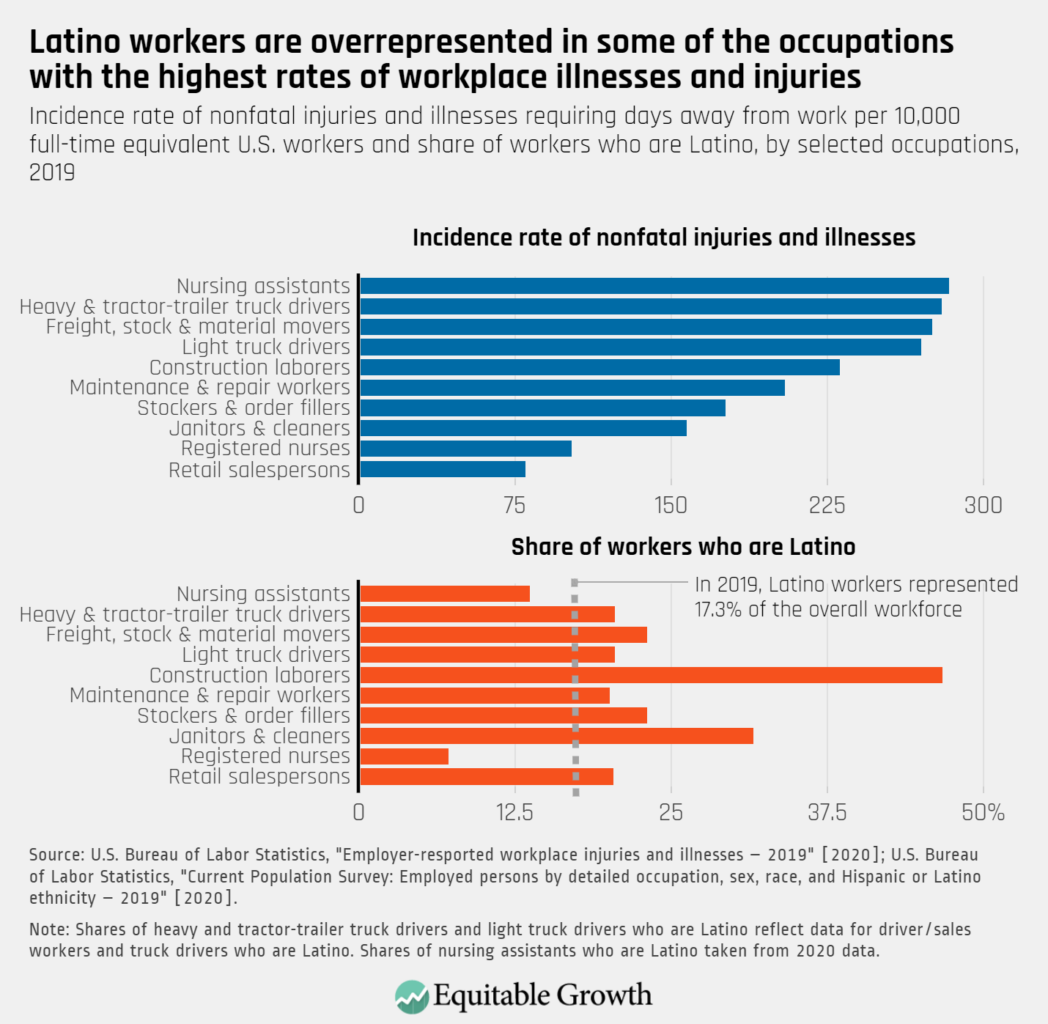

As with poor-quality schedules, overrepresentation in certain types of jobs is an important reason why Latino workers are disproportionately likely to experience dangerous working conditions. Indeed, Latinos make up a large share of workers in some of the occupations in which incidences of both fatal injuries and nonfatal injuries and illnesses in 2019 were highest, representing about 21 percent of all truck drivers, 23 percent of all freight, stock, and material movers, and 47 percent of all construction laborers.

Overall, evidence suggests that even when accounting for level of formal education, Latino men who are not U.S. citizens are more likely to work in risky occupations than any other group of workers. (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7

In 2020, the COVD-19 pandemic triggered an explosion of work-related illnesses. The onset of the health crisis shifted the brunt of risky conditions at work toward nursing jobs—positions in which women in general, and Black women in particular, are greatly overrepresented.

For Latino workers, available evidence shows that overrepresentation in essential occupations and industries, such as agriculture (where crop and farmworkers often live in crowded housing), food processing and meatpacking plants (the sites of some of the worst COVID-19 outbreaks), food preparation and serving (where in-person interactions expose workers to infections), and construction (an industry in which very few workers have access to paid leave) play a large role explaining their higher-than-average COVID-19 infection rates.

Overall, Latino workers’ overrepresentation in dangerous jobs is compounded by language barriers that can keep many of these workers from receiving adequate safety trainings, create obstacles to access health insurance, foster greater dependence on labor income, and instill a fear of retaliation that can prevent workers from reporting unsafe working conditions. Fear of deportation also creates a chilling effect that keeps many Latino workers from raising concerns about hazards at work. This chilling effect extends to workers who are U.S. citizens or documented immigrants because Latinos are especially likely to live with or know someone who is undocumented.

Minimum wage standards

Gaps in legal protections leave millions of workers in the United States exposed to abuses and poor working conditions. For instance, many farmworkers and domestic workers are excluded from important provisions in the Fair Labor Standards Act, which establishes a federal minimum wage floor, child labor laws, and the right to overtime pay. Similarly, agricultural workers, domestic workers, and independent contractors are not covered by the National Labor Relations Act, which guarantees workers’ right to organize, form and join unions, and bargain collectively. And workers in private households are also excluded from standards and retaliation protections included in the Occupational Safety and Health Act.

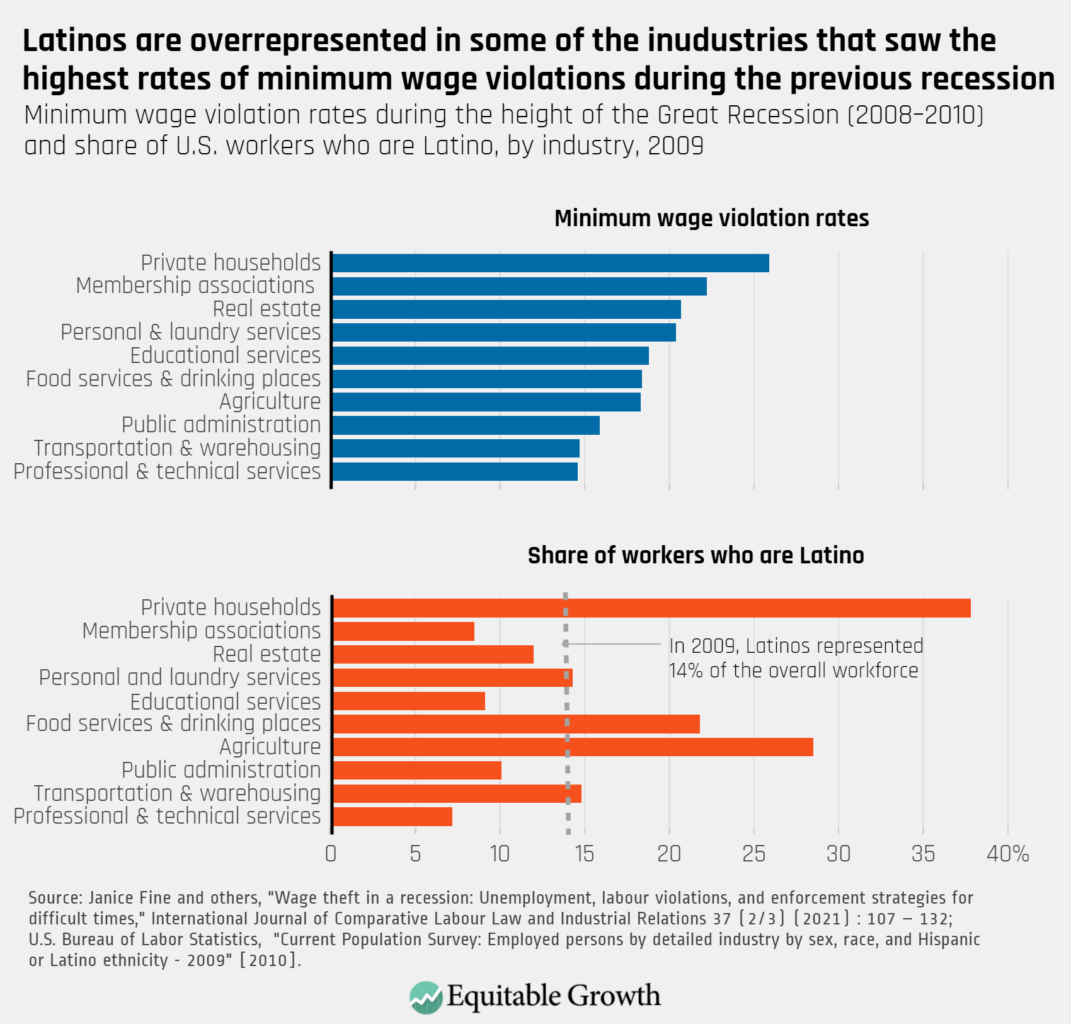

Latino workers are not only disproportionately likely to work in the domestic and agricultural jobs that are not covered by some of the country’s key labor protections, but also are overrepresented in occupations and industries in which outright violations to labor law are high. Research by Janice Fine, Jenn Round, and Hana Shepherd of Rutgers University and Daniel Galvin of Northwestern University shows, for example, that as wage theft rose in tandem with the unemployment rate during the Great Recession of 2007–2009, minimum wage violation rates were highest for workers in private households, membership associations, real estate, food services, and agriculture. (See Figure 8.)

Figure 8

Overall, violations of labor standards, such as wage theft, are regressive and exacerbate disparities in working conditions since they are much more likely to affect low-wage workers, particularly low-wage workers of color, and workers who are not U.S. citizens. For both Latino and non-Latino workers, then, shortcomings in the enforcement of minimum wage protections represent important threats to job quality and economic security. The same study by Fine, Galvin, Round, and Shepherd finds that the average amount workers lost to minimum wage violations during the Great Recession represented 20 percent of their hourly wage.

Labor unions and worker power help increase job quality

While many U.S. workers are exposed to poor scheduling practices, unsafe working conditions, and labor law violations, research finds that unions can push back against these bad-job traits in a number of ways. For instance, research shows that greater union coverage is associated with a decline in violations to labor regulations, including those enforced by the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the U.S. Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division, and the National Labor Relations Board.

Research also shows that unions boost support for measures that protect workers against illegal employment practices, with one study finding that states with higher union density are more likely to pass anti-wage-theft legislation. And because unions help workplaces meet U.S. labor laws and regulations, both academics and advocates have called for “co-enforcement,” in which government agencies partner with labor and community-based organizations to encourage, help, and generate support for workers filing complaints of violations by their employers.

In addition, there is strong evidence that unions help make workplaces safer. Research on the manufacturing sector by David Weil at Brandeis University finds, for instance, that union establishments are substantially more likely to enforce health and safety regulations than nonunion establishments. Similarly, in a recent study, Adam Dean at George Washington University, Jamie McCallum at Middlebury College, Simeon Kimmel at Boston University, and Atheendar Venkataramani at the University of Pennsylvania find that the presence of a labor union in nursing homes is associated with lower COVID-19 infection rates. Indeed, the team of researchers shows that in unionized nursing homes, resident COVID-19 mortality rates and staff COVID-19 infection rates were 11 percent and 7 percent lower, respectively, than in nonunion nursing homes.

There many other ways in which unions improve job quality. Union workers are much more likely to successfully apply for Unemployment Insurance benefits after involuntarily losing a job, and union members are more likely to have access to employer-sponsored benefits, such as health insurance, paid sick leave, and retirement plans, than their nonunion counterparts.

Workers belonging to unions also have what researchers call a union wage premium—earnings that are higher than for otherwise-similar nonunion workers. While union members in general benefit, the boost in pay that Black and Latino workers get by belonging to a union is especially large. For Latino workers and workers in the United States overall, labor unions and the ability to bargain collectively offer recourses against employer retaliation, mechanisms to better enforce labor laws and regulations, greater equity in pay, and job security.

Conclusion

A good job is one of the most important paths to economic security. That’s why addressing occupational segregation, enacting Fair Workweek laws, ensuring workplace safety, enforcing labor standards, and making it easier for workers to join or form a union are all essential for Latino workers—and U.S. workers overall—to access high-quality employment opportunities and for the U.S. economy to deliver broad-based, and thus more sustainable, growth.

Indeed, measures such as extending collective bargaining protections under the National Labor Relations Act to independent contractors, domestic workers, and agricultural workers would be an important step toward creating higher-quality jobs in sectors of the U.S. economy that too often have poor working conditions.