Better data collection can help lift the LGBTQ+ community out of economic hardship in the United States

Over the past 2-plus years amid the COVID-19 pandemic, widespread evidence has underscored the reality that various communities and demographic groups in the United States experience socioeconomic hardships differently. Numerous studies have explained how communities of color have experienced greater rates of job loss, financial instability, and negative health outcomes than their White counterparts.

This information is known largely because of disaggregated data collection that asks respondents specific questions about their race and ethnicity. Federal surveys, for instance, that ask such questions provide insight into the economic well-being of different demographic groups and how they are treated by society with respect to their identities.

Yet one group is often overlooked in federal data collection: the LGBTQ+ community. Currently, only the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey—just one of the dozens of federal economic surveys—asks demographic questions explicitly related to the respondents’ sexual orientation or gender identity, or SOGI. (While the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey does not ask people to self-report their sexual orientation or gender identity, some research has nonetheless leveraged this survey using self-reported data on partners of the same sex who live in the same household, but this represents a small fraction of all LGBTQ+ households.) This lack of data limits our understanding of the LGBTQ+ community’s economic experiences, which, in turn, limits policymaking that could provide essential support targeting the specific needs of LGBTQ+ workers and families in the United States.

The need for more federally collected data on the LGBTQ+ community was the focus of an event that the Washington Center for Equitable Growth hosted on July 12. This latest installment of Equitable Growth Presents, titled “LGBTQ+ Economic Data and Disparities: What We Still Need to Know,” was a virtual convening featuring Lee Badgett, professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and Sharita Gruberg, vice president of economic justice at the National Partnership for Women and Families, and was moderated by Equitable Growth’s Director of Economic Measurement Policy Austin Clemens.

Badgett kicked off the event, summarizing her research on the economic experiences of the LGBTQ+ community, which focuses on how sexual orientation and gender identity shape economic outcomes. While labor economists often discuss gender or racial wage divides, Badgett’s research looks at the wage disparities between gay and lesbian or bisexual men and women and their heterosexual peers—for example, emerging literature finds that gay and bisexual men earn 7 percent to 11 percent less than their heterosexual counterparts. There is suggestive evidence that this pay divide is the result of discrimination, as it tends to widen in regions where there are fewer legal protections against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity and shrinks where more protections are in place.

Badgett explained her findings that lesbian women earn 7 percent to 9 percent more than heterosexual women, while bisexual women earn 10 percent less than heterosexual women. She attributes this inverted gap to the labor experiences of lesbian workers in the United States. Data show, for example, that lesbian women work more hours and weeks in a year, compared to heterosexual women. At the same time, Badgett reiterated that all women, regardless of sexual orientation, earn less than gay, bisexual, and heterosexual men.

Badgett also discussed her work examining how earnings vary before and after an individual’s gender transition. She finds that trans women face an earnings drop, while trans men face little to no changes in earnings post-transition. These findings indicate that both stigma against transgender individuals and wage gaps between cisgender males and females play a role in how an individual is compensated after their gender transition.

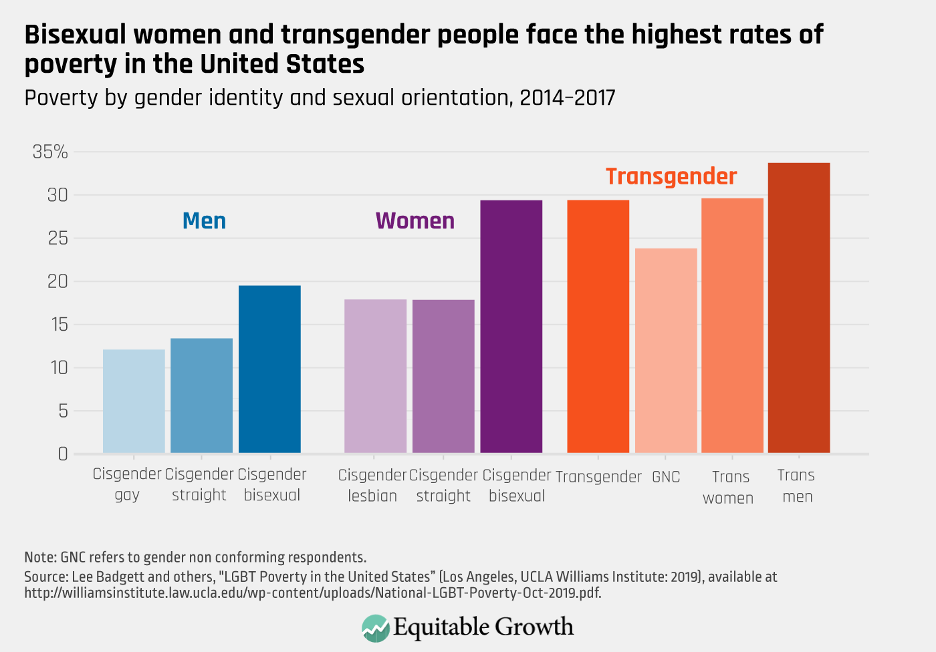

At a time when transgender and gay rights are threatened in states across the country, understanding the socioeconomic challenges faced by this community is vital. Badgett’s research finds, for example, that LGBTQ+ people face higher rates of poverty than cisgender and heterosexual people. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The main contributor to these high poverty rates is discrimination. Experimental studies on hiring processes, for example, find that resumes with LGBTQ+-coded language—such as including gender non conforming pronouns—were 35 percent less likely to get called for an interview than resumes without such language. In an economy where most people rely on employment to receive health insurance, discrimination that makes it difficult to obtain or keep employment can create healthcare access inequities. This system can further trap an already-vulnerable population into greater poverty.

After Badgett presented her research, NPWF’s Gruberg explained that the first step to tackling this issue is to collect more data on the economic and lived experiences of LGBTQ+ Americans. Gruberg praised the Census Household Pulse Survey, which began asking SOGI questions in 2021, as a tool allowing researchers to better understand the disparities LGBTQ+ people have faced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet as valuable as the Household Pulse Survey is in breaking down the effects of the pandemic, Badgett and Gruberg pointed out that it is still very limited in what it tells us.

Gruberg also highlighted two major successes in the campaign to collect more disaggregated data for the LGBTQ+ population: the LGBTQI+ Data Inclusion Act and the Biden administration’s executive order on Advancing Equality for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Intersex Individuals.

The LGBTQI+ Data Inclusion Act, which passed in the House and has been introduced in the Senate, would require federal agencies that administer surveys to individuals to ask for voluntary self-identification of sexual orientation and gender identity on those surveys. As mentioned above, this data collection is essentially limited to the Household Pulse Survey, which is the first—and currently only—economic survey to explicitly feature such questions. Private institutions have tried to fill the gaps in the data by conducting their own surveys of the LGBTQ+ community. But to capture accurate and nationally representative statistics, the federal government needs to take on the responsibility of collecting thorough data on LGBTQ+ Americans.

Meanwhile, President Joe Biden’s executive order addresses the discriminations LGBTQ+ people face in schools, housing, healthcare, the judicial system, and employment, as well as in accessing federal programs. It also “establishes a new federal coordinating committee on SOGI data, which will lead efforts across agencies to identify opportunities to strengthen SOGI data collection.”

The combined efforts of the executive order and the LGBTQI+ Data Inclusion Act indicate that a “whole of government” approach to collecting meaningful data on the LGBTQ+ population, while also protecting their privacy, can provide clarity on the unique economic metrics and outcomes of LGBTQ+ individuals. These actions will greatly expand our understanding of the economic and lived experiences of LGBTQ+ people in the United States and thus guide policymakers in crafting legislation that responds to the specific economic hardships of—and that builds equity for—this often-overlooked community.