Advancing research and evidence on child care and U.S. economic growth

Research shows that accessible and affordable child care is both a lifeline for working families and a driver of growth across the entire U.S. economy. A functioning child care market has the potential to grow the economy through several distinct channels: assisting parents who choose to pursue work, helping children grow and develop their human capital, and providing high-quality jobs for caretakers.

These mechanisms of growth have been discussed by scholars for decades, but further research would help policymakers establish and fine-tune a functioning child care system in the United States that maximizes the potential for economic growth. With that in mind, Equitable Growth recently convened more than 30 economists, social scientists, policymakers, and advocates to discuss research questions and needs that could further shed light on the important role that child care plays in propping up the overall economy, as well as policy strategies that could help shore up the U.S. child care industry.

This meeting was part of Equitable Growth’s Child Care Research Accelerator initiative, which furthers our commitment to advancing research and evidence that supports broad-based and sustainable economic growth. In addition to serving as an important discussion forum, the convening uncovered new opportunities for research, which has helped to inform the funding strategy for Equitable Growth’s 2023 Request for Proposals.

This column summarizes some of the research questions and themes discussed at this convening, and then outlines Equitable Growth’s research priorities around child care and early education going into our 2023 grantmaking cycle.

The gaps in research on child care and U.S. economic growth

Researchers at Equitable Growth’s recent child care convening raised several different areas where further research on child care and early education would be valuable. These research questions focus on the foundational relationship between early care and education and the economy, sectors of the child care market that have been underinvestigated in prior research, and new research opportunities offered by policy change. Below, we look at these topics in more detail.

Updating estimates of the labor market impacts of child care price changes

One underling theme of recent research on the potential impact of increasing public investments in child care on economic activity are estimates of parents’ elasticity to employment to child care prices. In other words, how much more or less will parents work if child care prices increase or decrease?

In her review of the literature, Taryn Morrissey of American University reports that a 10 percent reduction in child care prices increases parental employment approximately 0.5 percent to 2.5 percent, indicating an elasticity of 0.05–0.25. Importantly, Morrissey notes, these estimates are smaller when using more recent data and data from international sources, suggesting that parents’ elasticity to employment is neither static nor homogenous.

A theme that emerged at the convening was that precise and current elasticity estimates are crucial to ensuring that policymakers have an accurate understanding of the economic impact of various early care and early education proposals. Economic models that rely on inaccurate or outdated elastic estimates have the potential to dramatically underestimate or overestimate changes in labor force participation resulting from child care investments.

Updating these price elasticity estimates should be a priority among researchers studying child care and early education in the U.S. economy. In addition, as parents tend to make employment decisions based on their preferences for child care type, quality, and geographic location, among other factors, as well as pure prices, future research also should aim to shed light on how these other factors impact employment decisions in relation to price elasticity.

Exploring the practices and experiences of home-based, underground, or less-identifiable care arrangements

A functioning child care market is one that offers a diverse range of care options to best meet the range of needs that arises in a given community. Research on families’ child care decisions reinforces the importance of care received outside of traditional child care centers. Yet researchers and policymakers alike have directed more of their focus toward these larger centers, while less is known about the size and economic impact of the home- and family-care markets.

Convening participants suggested this is largely an issue of identifiability and data access, rather than a failure to recognize the importance of noncenter providers. Many home- and family-based providers exist outside of the formal child care market, and public data on these provider types are limited. Future child care research should work to fill some of these gaps in the data on nontraditional child care options.

Several participants also advocated for research on U.S. military child care options. The U.S. military operates and funds a large and dispersed child care market for military families. While these facilities have generally been considered high quality, long waitlists have prompted recent efforts to expand the military’s child care infrastructure and community-based options. This unique child care market may be ripe for future research on government-provided child care.

Evaluating how the U.S. child care market responds to economic and policy change

Similar to nearly all sectors of the U.S. economy, child care does not exist in a vacuum immune from economic and policy change. Indeed, prior research from Chris M. Herbst at Arizona State University and Jessica H. Brown at the University of South Carolina describes child care’s asymmetrical exposure to macroeconomic trends. In other words, they find that in economic downturns, employment in the child care sector declines slightly faster than employment across the broader U.S. labor force, while child care job growth is significantly slower than other sectors in periods of recovery.

Further research from Brown also explores the possibility of unintended consequences in the child care market from early care and education policy changes. Due to necessary staff-student ratios, caring for infants and toddlers is more costly to providers than caring for preschool-age children, so older children’s care—bringing in tuition dollars while costing providers less—is often a vital source of profits keeping providers’ doors open. Brown finds that pre-Kindergarten expansion without accompanying public investment in infant and toddler care can negatively impact the child care market’s fragile economic stability by transferring this source of profit away from child care and toward early education.

Research has helped shed light on child care’s relationship with macroeconomic and policy trends, but further examination is needed to help policymakers understand how the child care market may respond to shifting economic conditions and investment options. Some potential research questions include:

- How is child care responding to interest rate increases and tightening or loosening labor market conditions?

- Do minimum wage increases meaningfully impact child care labor supply and the price of care?

- How will changes in the size of child care subsidies and access to child care spill over to nonsubsidized populations?

- To what degree does public investment stabilize the child care market from macroeconomic shocks?

New funding models and program types stemming from the American Rescue Plan may offer researchers important state-level policy variation for studying these and other policy-relevant questions.

Investigating child care’s role in children’s human capital development relative to early education

A growing body of literature suggests early education programs, such as Head Start and universal pre-K, have the potential to meaningfully support young children’s human capital development, leading to short-term academic advantages and long-term socioeconomic benefits. Convening participants were largely confident this research shows early education’s effects on human capital, even if the literature has yet to firmly define the “secret ingredients” that lead to these outcomes.

The plausible mechanisms for early education’s boon for long-term human capital development—including the formation of self-regulation and attention skills and the opportunities to develop and test social skills—may also be present in some child care settings. Practitioners and advocates have suggested that the distinction between child care and early education may not be as rigid as early childhood policy often suggests.

Researchers should further investigate the potential mechanisms for long-term human capital development in child care settings and if or how they differ based on provider type and care practices. Such research may assist practitioners and policymakers in supporting a holistic early care and education system that maximizes positive socioeconomic outcomes in the long term.

Equitable Growth’s 2023 child care and early education funding priorities

Equitable Growth uses conversations such as those had at our recent child care convening and at our 2020 research roundtable of child care scholars to identify new research questions and priorities for our 2023 grantmaking cycle. This year, Equitable Growth is prioritizing research questions and projects that probe child care’s symbiotic relationship with the broader economy in which we all work and live.

Examples of research topics that are in line with this year’s funding priorities are:

- Updating estimates on parents’ elasticity to employment to child care prices, as well as evidence on the mediating effects of child care quality, accessibility, and program type on employment

- Building evidence on child care and early education’s role as a barrier or facilitator to macroeconomic growth and stability, including how access to early care and education accelerates or moderates the ebbs and flows of the business cycle

- Investigating child care and early education’s impact on firm-related outcomes, including workers’ productivity, absenteeism, presenteeism, and employer-employee matching

- Determining child care’s role, relative to early education programs, in children’s human capital development and the long-term productivity impact of that development, and redefining short term indicators for human capital development to extend beyond test scores and education-related outcomes alone

- Clarifying the effects of local economic conditions, including the housing and labor markets and minimum wage laws, on the child care labor force and the accessibility and cost of care

- Examining the use of policy variation stemming from the American Rescue Plan or state-level policy changes, such as subsidy expansions, workforce development initiatives, or other programs, to shed light on the questions above

This list is illustrative rather than comprehensive—Equitable Growth will consider all research projects that build evidence on child care’s role in the U.S. economy, including those not listed. (Note, however, that in prior years, Equitable Growth has invested in mixed-methods projects that study the experiences and practices of home-based providers, and as a result, we are not prioritizing similar projects or research questions in 2023.)

Conclusion

Equitable Growth’s recent convening of scholars and policy experts fostered a range of discussions on important research questions, ideas, and opportunities on child care’s role in establishing broad-based and sustainable economic growth. This convening, in turn, shaped what the Washington Center Equitable Growth seeks to fund through our 2023 grantmaking cycle—in particular, academic research projects that can answer these and other policy-relevant questions that will inform early care and education policy.

Child care researchers interested in applying for funding support—or learning more about Equitable Growth’s other funding priorities—are encouraged to review the 2023 Request for Proposals for more information. Scholars can also contact grants@equitablegrowth.org to learn more.

Including immigrants in the U.S. tax system is fiscally responsible and can boost economic growth by lifting the well-being of their families

The recently enacted Inflation Reduction Act boasts the potential for more noncitizen immigrant workers and entrepreneurs to pay into the U.S. tax system, improving the federal government’s tax collection. What’s more, the way the IRS can go about bringing these workers and entrepreneurs into the U.S. tax system would facilitate the better delivery of targeted, anti-poverty benefits to already-eligible households to boost U.S. economic growth and productivity.

But there’s a catch. Some of the $80 billion in new funding for the IRS in the new law, which is expected to improve tax collection by auditing high-income earners, needs to be deployed toward enabling noncitizen workers and entrepreneurs to fulfill their lawful taxpayer obligations. Specifically, the U.S. Congress’ allocations can serve immigrants if the IRS prioritizes the administration of Individual Tax Identification Numbers, or ITINs—a nine-digit number that allows certain noncitizens to comply with their taxpaying obligations.

These ITINs not only allow entrepreneurs and workers to contribute billions of dollars to public coffers but also will facilitate targeted tax credits to economically vulnerable households and children, thus advancing more immigrant-inclusive policies through U.S. tax system, including for the citizen children of immigrants. But this will require the IRS to use some of its expanded funding from the Inflation Reduction Act to help noncitizen workers and entrepreneurs file their lawful federal taxes.

In short, by decreasing the barriers to the use of ITINs in tax filings, the IRS can advance economic prosperity for and by immigrants and in the U.S. economy more broadly.

In this column, I briefly examine how the budget reconciliation process that led to the enactment of the Inflation Reduction Act initially included proposed new pathways to lawful permanent residency and citizenship for undocumented immigrant workers that were ultimately considered inappropriate to be included in the budget reconciliation process. I then explore in detail the recent history of ITINs and noncitizen immigrant taxpayers to show how some of the $80 billion in new funding for the IRS can boost federal tax revenue substantially. I then examine how ITINs can improve long-term U.S. economic growth and productivity by channeling key tax credits, particularly to families with citizen children—boosting the human capital of the nation’s future generations of workers.

For this to happen, the IRS should provide new funding to make ITINs more accessible to noncitizen immigrants.

The Inflation Reduction Act’s initial immigration proposals

During the congressional debate over provisions to be included in the Inflation Reduction Act, immigration advocates tried and failed to use the reconciliation process to improve access to immigrant visas, green cards, and permanent residency, as well as provide temporary protection from deportation for long-time residents with work authorizations. These provisions could have contributed to strong, stable, and broadly shared economic growth by bringing more noncitizen immigrant workers and entrepreneurs into the federal tax system in the United States.

These provisions ultimately didn’t pass because they were deemed inappropriate for the budget reconciliation process, which typically only includes provisions that will affect the federal government’s bottom line. Yet the Inflation Reduction Act still offers an exciting opportunity for the IRS to use its resources to efficiently provide immigrants with ITINs.

But first, a brief primer on the history of ITINs.

The history of ITINs and immigrants

U.S. citizens accustomed to filing their own taxes with Social Security Numbers may be unaware of their noncitizen peers’ taxpaying experiences. Federal income tax obligations stem from residency, based on one’s length of stay, regardless of immigration status. As such, the IRS created the ITIN in 1996 so that noncitizens who may be ineligible for Social Security Numbers can comply with their tax obligations.

According to IRS estimates, millions of returns are filed by primary taxpayers with ITINs, reflecting billions of dollars of revenue added to federal coffers, even after accounting for the tax credits that many immigrant families use to reduce their federal tax liabilities. Unlike Social Security Numbers, ITINs may expire due to nonuse—if a migrant leaves the United States for a number of years, during which they have nonresident status and no legal obligation to file, they must apply for a new ITIN. In recent years, the IRS has received millions of applications for new ITINs.

The delays and difficulties faced by ITIN applicants have, for decades, attracted the scrutiny of the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of the Taxpayer Advocate, located within the IRS and led by the National Taxpayer Advocate. In 2003, for example, the National Taxpayer Advocate’s annual report to Congress highlighted the increasing demand for ITINs among immigrants in the United States, including for the purposes of demonstrating good moral character. Indeed, tax compliance, which may require an ITIN for those without Social Security Numbers, helps immigrants seeking pathways to lawful permanent residency and U.S. citizenship.

Yet despite attempts by migrants to comply with tax laws, securing and using ITINs raises challenges on many fronts. These include requiring ITIN applicants to file tax returns along with the ITIN application, as well as the IRS lacking sufficient staff to expeditiously process these ITIN applications and tax returns. Accordingly, the National Taxpayer Advocate wrote in its 2003 report that the “difficulty in obtaining assistance and the processing delays involved in receiving ITINs place a significant burden on individuals who are attempting to participate in the tax system and comply with the law.”

Two decades later, the onslaught of COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated the problems for immigrants seeking ITINs, with the National Taxpayer Advocate raising alarms anew and recommending reforms. These paper-processing delays already affected a broad universe of paper filers, but new ITIN applicants found pandemic-induced delays uniquely unavoidable. That’s because noncitizens are unable to e-file when seeking an ITIN number assignment and instead must attach their ITIN application to a paper tax return. Accordingly, the National Taxpayer Advocate encouraged the IRS to be more accommodating of ITIN applicants.

Better access to ITINs facilitates easier voluntary tax compliance, contributing to the billions of dollars of ITIN-filer tax collections. More specifically, the revenue benefits come not only from noncitizen taxpayers employed by U.S. firms but also from noncitizens who may be employers themselves. Despite prohibitions on employing undocumented immigrants, undocumented employers can and do hire documented workers. The use of ITINs can boost fiscal contributions from undocumented immigrant entrepreneurs and their workers.

The U.S. Congress in 1996 also barred ITIN-holding immigrants from receiving certain public benefits by requiring Social Security Numbers to access those benefits. More recently, because of Congress’ definition of a “valid identification number,” the initial rounds of direct pandemic relief payments in 2020 from the IRS penalized even Social Security Number-carrying people because they either were married to noncitizens or were the children of noncitizen parents—even when those same adults had ITINs and perfect tax compliance. Aggrieved U.S. citizens filed lawsuits claiming that their ineligibility for the IRS payments based on their personal relationships violated their constitutional rights, and in subsequent rounds of relief, Congress narrowed some, but not all, exclusions.

This brings us to the taxpayer benefits and refundable tax credits facilitated by ITINs, including the refundable federal Child Tax Credit, as well as potential state benefits. The U.S. Congress has long allowed ITIN-holding noncitizen parents to claim the Child Tax Credit for children who are U.S. citizens. And even as ITIN-holders are excluded from the federal Earned Income Tax Credit, many states may allow ITIN holders to claim parallel state-level Earned Income Tax Credits, including in my home state of California.

As such, an ITIN is not only in itself a taxpayer service, but also a conduit for other social infrastructure services and benefits. By facilitating targeted tax credits back to vulnerable households and children, ITINs expand the reach of these economic relief programs, thereby advancing the goals of federal and state legislators to create more equitable and stronger economic growth in the future.

How the Inflation Reduction Act can broaden access to ITINs

While the more-explicit immigration provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act may have failed, prioritizing immigrant access to ITINs is something for which the IRS has both the power and financial resources. The IRS, for example, could work toward allowing for the electronic processing of ITIN applications, even without a completed tax return. And a group of organizations working with immigrant taxpayers recently recommended that the IRS improve its Certified Acceptance Agents network, which provides in-person verification of identity documents.

Beyond expanding the number of CAAs, the IRS should also consider how to locate them in places that are accessible for immigrant taxpayers. (To that end, the IRS currently has a moratorium on new CAA applications until 2023 as it pursues modernization and efficiency updates.) If the electronic processing of ITINs is enabled, it will allow immigrants’ economic contributions to enrich the public fisc because of currently uncollected tax revenue flowing into the IRS and improve the lives of the vulnerable households and children that inspired legislators to design various anti-poverty tax credits in the first place.

In sum, the IRS’s new funding can strengthen ITIN administration. The IRS can and should use its resources to efficiently provide immigrants with ITINs, which would provide greater federal tax revenue and facilitate targeted, anti-poverty benefits to already-eligible households. In expanding ITIN access, the IRS would support U.S. economic growth and productivity now and in the future, including for the U.S. citizen children of noncitizen immigrant taxpayers who would benefit today from greater investments in their future human capital.

Green jobs are good for U.S. workers and the U.S. economy

Earlier this year, the U.S. Congress passed and President Joe Biden signed into law one of the most consequential climate bills in U.S. history. The Inflation Reduction Act allocates $369 billion to clean energy and electric vehicle tax breaks, domestic manufacturing of batteries and solar panels, and pollution-reduction efforts.

In addition to mitigating the effects of climate change and driving consumption of renewable energy, these investments will add jobs in the clean energy sector—some estimates say as many as 912,000 per year over the next decade. As employment in the fossil fuel industry dwindles amid changes in U.S. energy markets, new research suggests that the growth in renewable energy benefits U.S. workers and is particularly good for workers who live in areas with high rates of employment in fossil-fuel extraction industries.

The paper, co-authored by E. Mark Curtis of Wake Forest University and Ioana Marinescu of the University of Pennsylvania, develops a measure of green jobs—specifically, occupations in the solar and wind energy fields. Using data from Burning Glass Technologies, a labor market analytics firm, on job postings in the United States, the authors find that green jobs saw incredibly strong growth in recent years—a trend that they find is, overall, quite beneficial for workers.

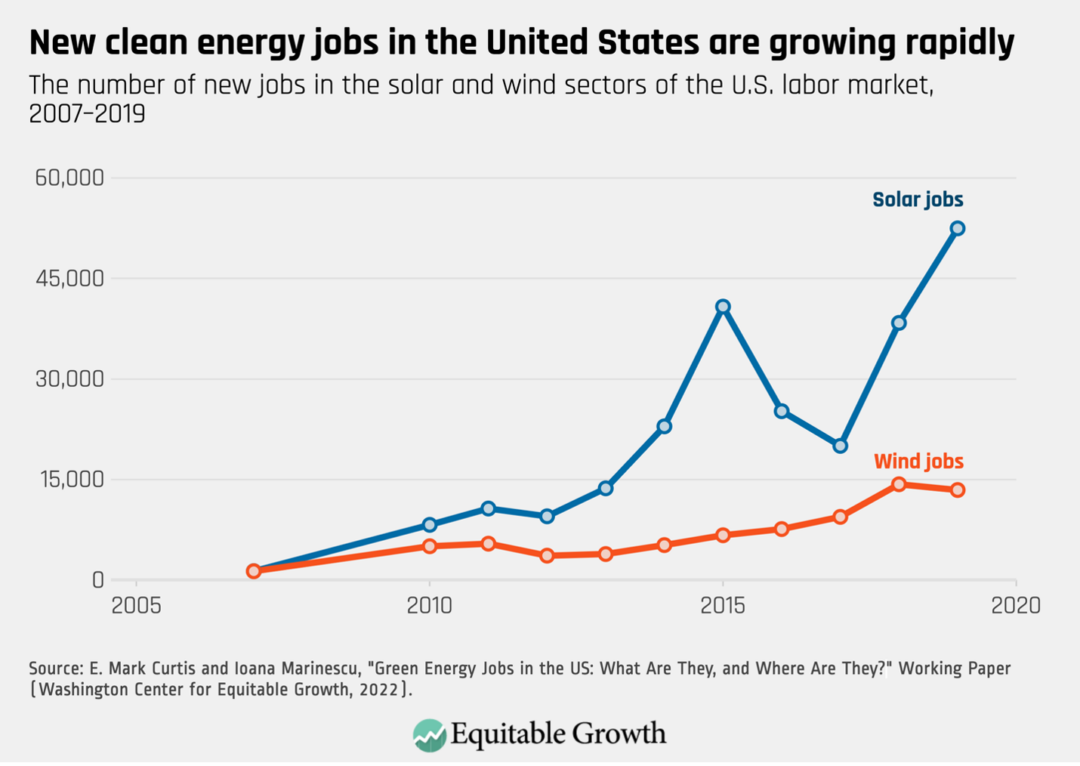

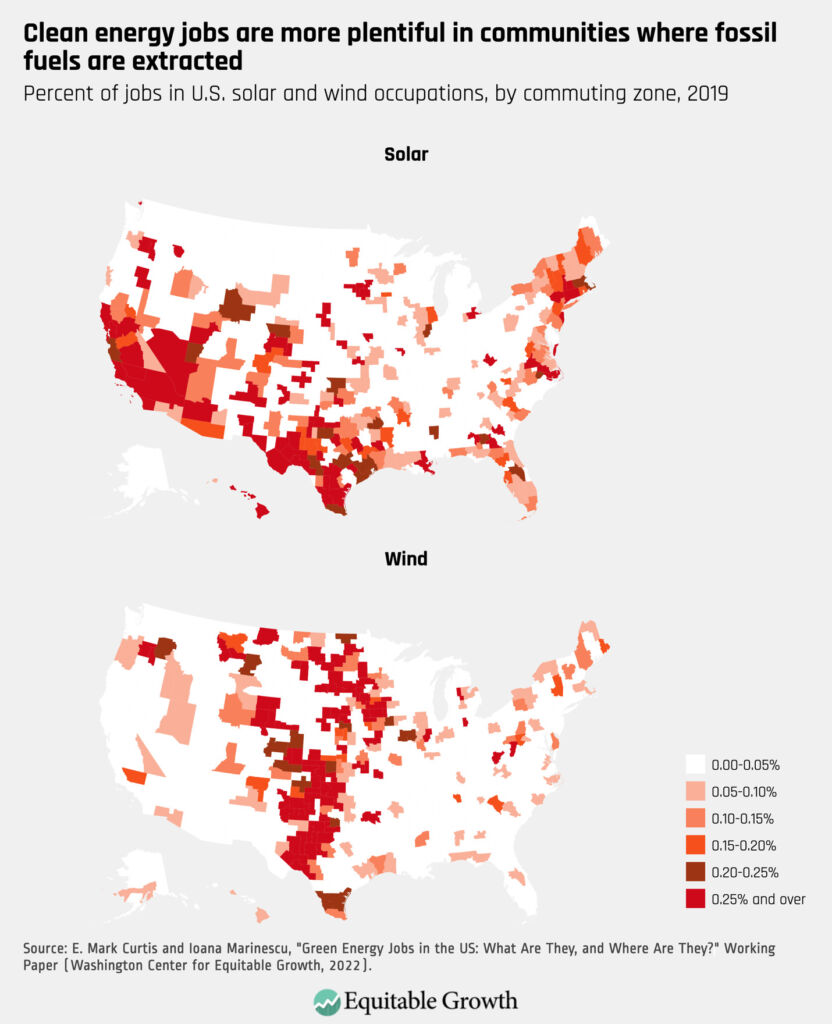

Indeed, jobs in the solar energy industry increased approximately five-fold since 2013, with more than 52,000 postings in 2019 alone. That same year, there were about 13,500 wind job openings—triple the number before 2013. By way of comparison, the number of new fossil-fuel jobs in 2019 was around 44,000. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

To be sure, these findings are based on job postings for open positions and do not necessarily reflect filled positions or work actually being done. Nevertheless, this trajectory closely follows the growth in solar and wind electricity production in the United States in the same time period, thougH interestingly wind electricity makes up a larger share of energy production than solar—despite there being more solar jobs than wind jobs. The authors posit that this discrepancy may be a result of different technologies in the two sectors, including the larger number of workers needed in the solar industry than the wind industry to produce the same amount of electricity.

Curtis and Marinescu also find that green jobs tend to be in occupations that are about 21 percent higher-paying than the average in other industries—including fossil-fuel extraction—with the pay premium being even greater for green jobs with low educational requirements. They also find that green jobs in general have the same educational requirements as other jobs, with about 40 percent requiring only a high school degree.

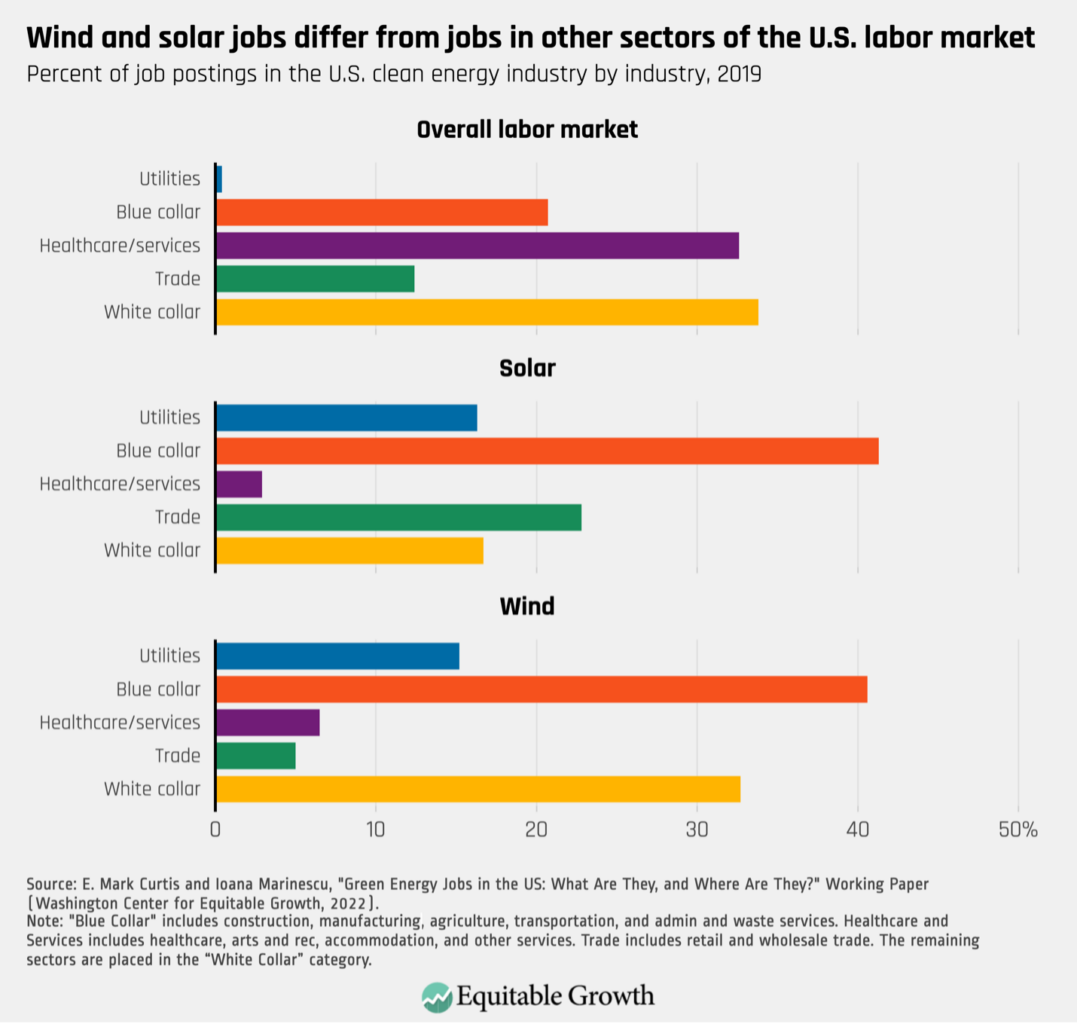

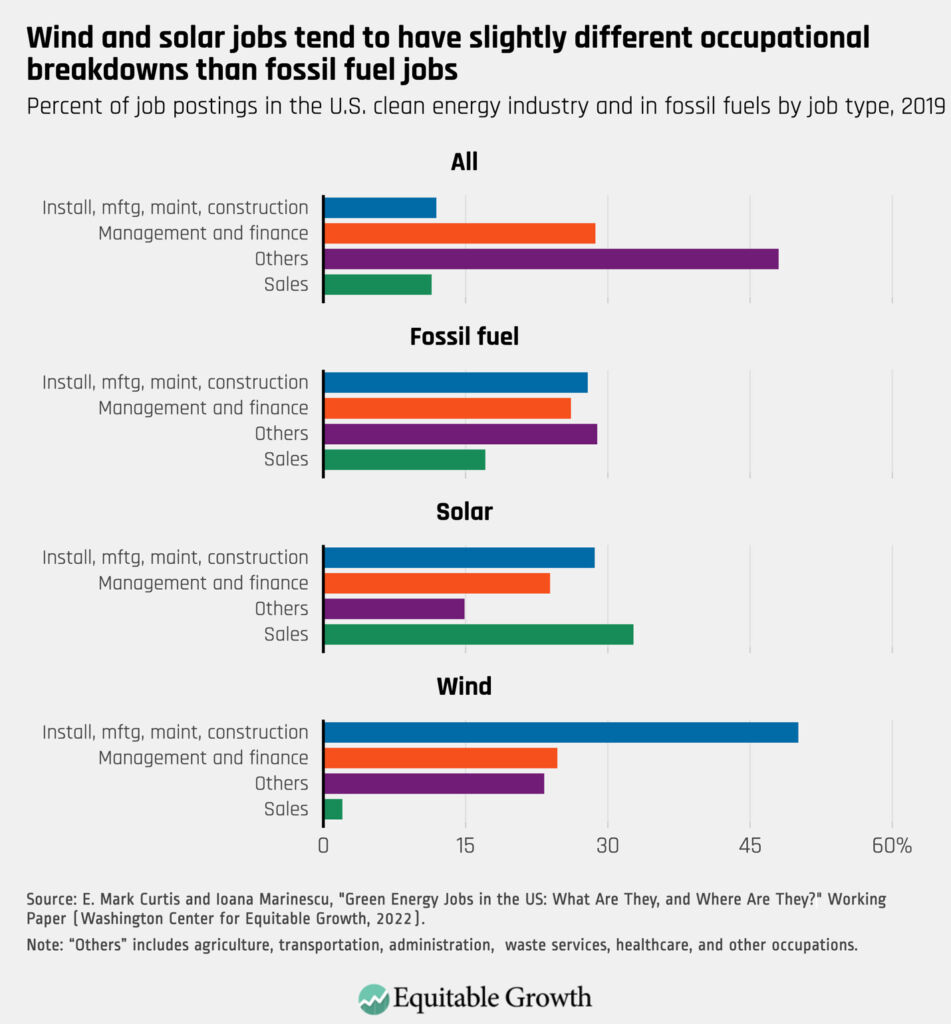

About one-third of solar jobs are in sales occupations, while about 37 percent of wind jobs entail installation, manufacturing, maintenance, and construction. Around a quarter of all jobs in both wind and solar are in management and finance occupations, while close to 30 percent of fossil fuel jobs are listed as “other,” which includes anything from agriculture, waste services, transportation, administration, and other services. (See Figures 2 and 3.)

Figure 2

Figure 3

In general, in terms of occupational classification, green jobs are more similar to fossil-fuel jobs than to all other jobs in the U.S. labor market—yet, as the authors find, green jobs tend to be specifically in occupations that pay more. This suggests that the coming renewable energy boom will create high-paying job opportunities for many U.S. workers, and especially for low-skilled workers.

Curtis and Marinescu also find that green jobs, while unevenly distributed across the country, tend to be located in communities with a high share of employment in the oil and gas industry, such as Texas and across the Midwest. They propose that this correlation could be due to geographic conditions that favor both renewables and fossil fuels—for instance, they write, more wind in the mountains where coal is extracted. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

The co-authors also find that solar jobs tend to be located in commuting zones with higher non-White populations, while the opposite is true for wind jobs. They hypothesize this could have to do with where solar and wind jobs are mostly located and the demographic makeups of these areas. In other words, as Figure 4 displays, many solar jobs are in the southern half of the United States, from California through Florida, where there is a bigger non-White population, whereas wind jobs are largely in the Midwest, where fewer non-White people tend to live.

The fact that green jobs and fossil-fuel jobs tend to be located in the same areas, along with the occupational similarities and job requirements in the two industries, suggest that many job losses in oil and gas that result from a renewable energy boom may be offset by an influx of clean energy jobs. The transition from a carbon-intensive economy to a green economy therefore may be smoother than previously predicted.

Indeed, this study presents a new angle to the debate over the move to a low-carbon economy. While most previous work has focused on jobs and wages lost from moving away from fossil fuels, Curtis and Marinescu instead highlight the benefits of this new, cleaner economy. It is likely that these results, as well as those from similar research on green jobs, will be helpful in guiding policymakers as they work to allocate funding from the Inflation Reduction Act and spur a renewable energy labor boom.

Enacting a minimum wage for tipped workers is on the ballot in two U.S. cities. Here’s what the research says

In most cities and states across the United States, servers and other so-called front-of-house staff in the restaurant industry earn a subminimum wage for tipped workers. Whether and how this long-established and historically racist and gender discriminatory two-tiered compensation system harms these restaurant workers to the benefit of restaurant firms is the subject of increased debate across the country. The reason: there are ballot initiatives this month to enact fixed minimum wages for tipped workers in Washington, DC and Portland, Maine, and the idea is highly debated in other cities and states across the nation.

So, what do the economic data tell policymakers—and the general public weighing the merits of these ballot initiatives—about the impact of the subminimum tipped wage on servers in the restaurant industry and about the efficacy of enacting a standard minimum wage for these workers? There are a number of research papers that examine the practice of tipping in worker outcomes, as well as the broader impact of a subminimum wage for tipped workers on the U.S. labor market. As cities and states across the country navigate debates on subminimum wages and whether to abolish their existence in favor of one fair wage, this column elevates the scholarly research to help inform this debate.

But first, it’s important to provide some context and some history about the tipped subminimum wage. The subminimum wage for tipped workers at the federal level stands at $2.13 per hour—far below the federal minimal wage of $7.25 per hour—but varies by state and city across the country. In some locations, the subminimum wage is higher than the federal level of $2.13 but still below the federal minimum of $7.25. In West Virginia, for example, the subminimum wage is $2.63, 50 cents more than the federal subminimum. And in seven states, as well as the territory of Guam, there is no subminimum wage for tipped workers, meaning all workers in these states earn the statutory minimum even in industries where tipping is common, including in the large state economy of California.

These state- and municipal-level reforms to the tipped minimum wage reflect efforts to address widespread wage theft and income volatility among tipped workers. The history of tipping’s roots in the larger structural racism of the U.S. labor market is an important consideration, too. Tipping was a practice that justified meager wages for Black workers in service occupations, such as railroad porters and bellmen in the 19th century, which spread quickly to the then-growing hospitality industry to include waiters and waitresses, resulting in rising gender wage discrimination, too, in restaurants.

While there was movement in the early 1900s to end the practice of tipping, business opposition to banning tipping in favor of a fixed wage resulted in tipped occupations being excluded from the introduction of the federal statutory minimum wage in the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. Even though federal law today stipulates that workers need to be paid the difference between the subminimum and the minimum wage if a worker’s tips are insufficient to match the difference, workers in many states and cities rarely receive this additional payment from their employers. As a result, de facto wage theft is rampant in the restaurant industry to this day.

So, what does the economic research tell us today about the consequences of the subminimum tipped wage for servers in the restaurant industry? Do reforms to the tipped minimum wage increase the wages of these workers overall? Or do reforms actually lead to decreased earnings for servers, as is believed by many in the restaurant industry? And does raising the tipped minimum wage have any discernible impact on employment outcomes for servers overall in the restaurant industry?

The economics research on the impact of the subminimum wage on these workers is somewhat ambiguous, finding some or no improvement in wages and unclear impacts for employment levels. But against the backdrop of low earnings for many workers in food and beverage serving occupations, efforts to stabilize wages by abolishing the subminimum wage for tipped workers may reduce the likelihood of wage theft and ensure that marginalized groups are not further disadvantaged. Additionally, abolishing the subminimum wage can reduce earnings volatility, which can have subsequent impacts on workers and their families.

Let’s now briefly examine some of this research.

Economists Sylvia Allegretto and Carl Nadler at the University of California, Berkeley find in their 2015 report, “Tipped Wage Effects on Earnings and Employment in Full-Service Restaurants,” that a 10 percent increase in wages for tipped workers in full-service restaurants increases earnings by 0.4 percent, with no discernible impact on employment levels. In contrast, economists William E. Evan at Miami University in Ohio and David A. MacPherson at Trinity University find in their 2013 paper, “The Effect of the Tipped Minimum Wage on Employees in the U.S. Restaurant Industry,” that earnings do go up, but employment goes down.

The ambiguity of these findings between marginally higher earnings but possible downside effects on employment levels could be troublesome for policymakers, but the earnings stability for these workers found by both pairs of researchers is certainly a worthwhile economic policy objective. What’s more, those restaurant workers most in need of earnings stability—young, low-income workers with families to care for—are particularly vulnerable to the clear downsides of subminimum tipped wages. Sociologists Michelle Maroto at the University of Alberta and David Pettinicchio at the University of Toronto find in their 2022 paper, “Worth Less? Exploring the Effects of the Subminimum Wage on Poverty Among U.S. Hourly Workers,” that subminimum wages were associated with increases in family poverty by 1.4 percentage points.

Maroto and Pettinicchio, however, do find that in some instances, having youth and students working for a subminimum tipped wage was associated with a decrease in family poverty, but also that subminimum wage work “compounded already high poverty rates for hourly workers with disabilities.” Further research that disaggregates the data in the subminimum tipped wage by age, gender, race, and household income would certainly be welcome, not least because the restaurant industry often showcases a carefully selected group of tipped employees who are garnering high levels of tips, as if the size of these tips is uniform across the industry when aggregated together. Advocates for tipped minimum wages find that is not the case.

Other research examining how restaurant servers in particular benefit in terms of total wages in states and cities with a fixed minimum wage, compared to those with subminimum tipped wages still in place, finds that minimum wage policy reforms are not worthwhile. Economists John E. Anderson at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln and Őrn B. Bodvarsson Westminister College in Salt Lake City find in a 2005 paper, “Do higher tipped minimum wages boost server pay?” that “1999 data on waitpersons and bartenders” show little evidence that there is a wage premium for these workers “in states with more generous minimum wages.”

It is important to emphasize, however, that similar outcomes across states refute outsized claims that getting rid of the subminimum wage will be disastrous for workers who would be subject to fair wage laws and the industries in which they work. Research in 2016 by economist T. William Lester at San José State University, for example, captures some important other factors related to higher labor standards in full-service restaurants in San Francisco, where fair wage standards were enacted several years ago, compared to the Research Triangle Park in North Carolina, where subminimum tipped wages remain the standard. He finds a number of important effects from the introduction of fair wage laws in the former market and the continuation of monopsonistic labor practices in the latter. Yet Lester also finds that neither the servers nor the restaurants in either place registered demonstrably terrible results from reform on the one hand and no reform on the other.

And then, there’s the broader question of family well-being—specifically, the quality of the future human capital of the children of restaurant workers in the United States. Epidemiologists Sarah Andrea at the University of Washington School of Public Health and her four co-authors at the Oregon Health and Science University’s School of Public Health conducted a nationwide investigation of the impact of the tipped worker subminimum wages on the gestational period of infants born to restaurant workers. They find that infants born to mothers working for subminimum wages have lower birth weights—one key negative factor in the subsequent physical and mental development of those infants. The five researchers conclude that “increasing the subminimum wage may be one strategy to promote healthier birthweight in infants,” which, in turn, would improve the future economic well-being of those children.

Clearly, economic debates about whether a subminimum wage for tipped workers increases wages on the margin or reduces employment on the margin is not the whole story when it comes to restaurant workers and their families. Earnings stability and the consequences for family economic well-being need to be considered in the mix, too.

Equitable Growth’s Jobs Day Graphs: October 2022 Report Edition

On November 4, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released new data on the U.S. labor market during the month of October. Below are five graphs compiled by Equitable Growth staff highlighting important trends in the data.

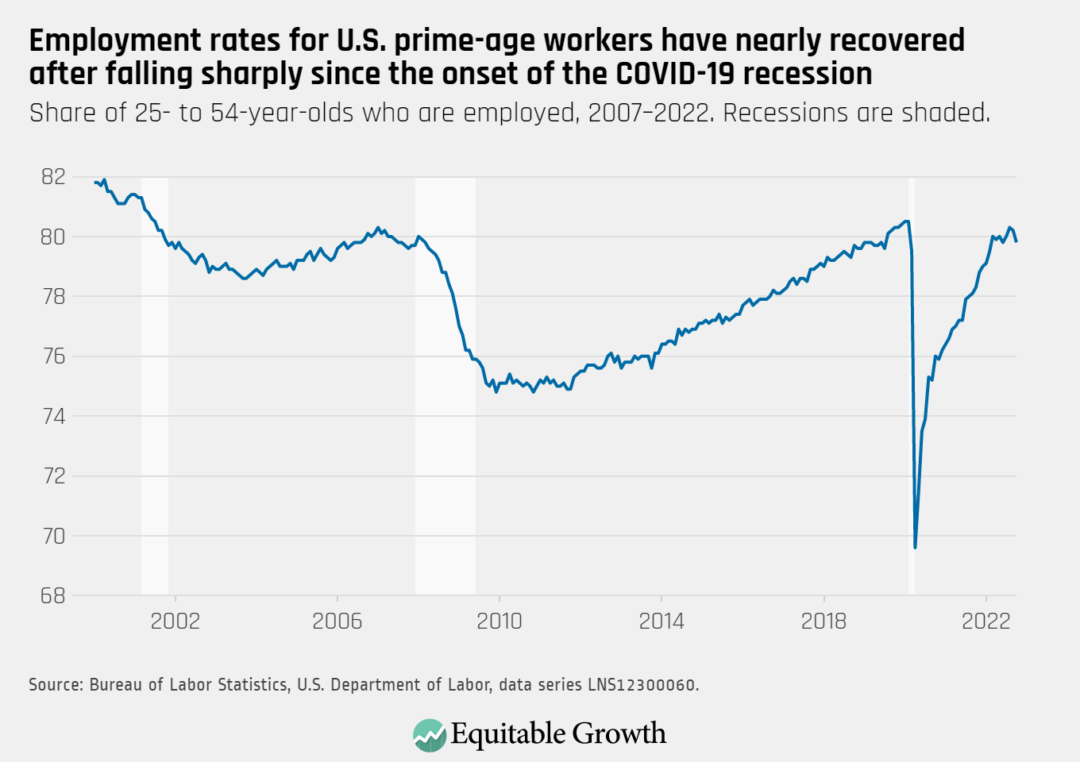

Job growth declined in October, with the prime-age employment rate falling to 79.8 percent and below 80 percent for the first time since June.

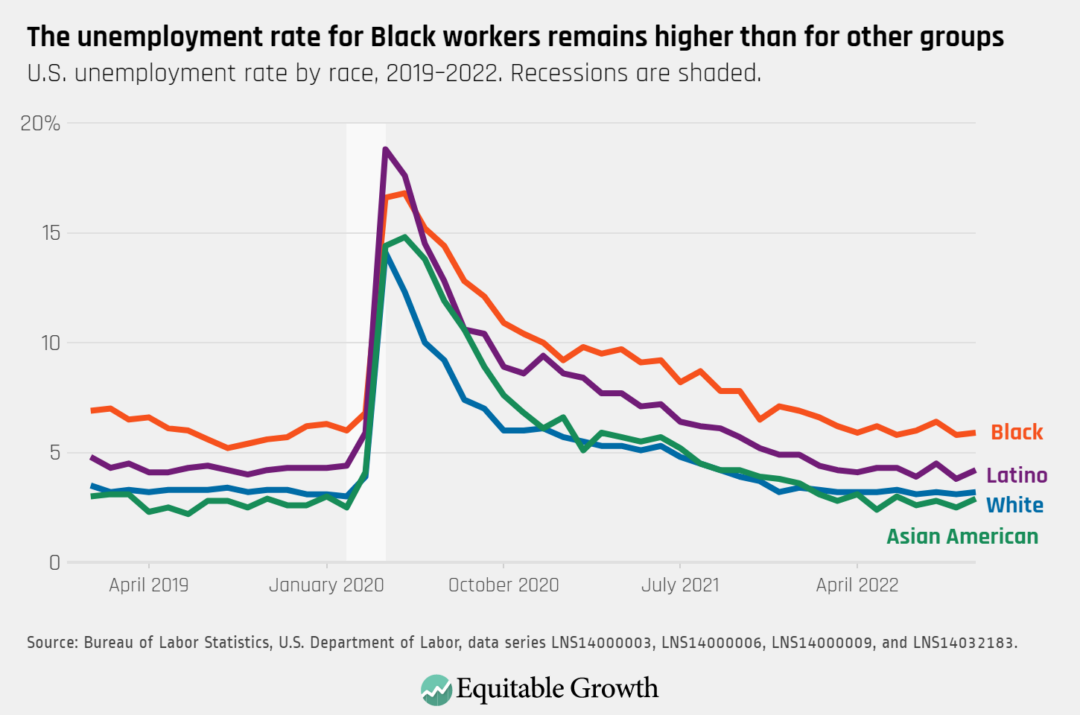

The unemployment rate increased for almost all major demographic groups, with the biggest increases for women and Hispanic workers.

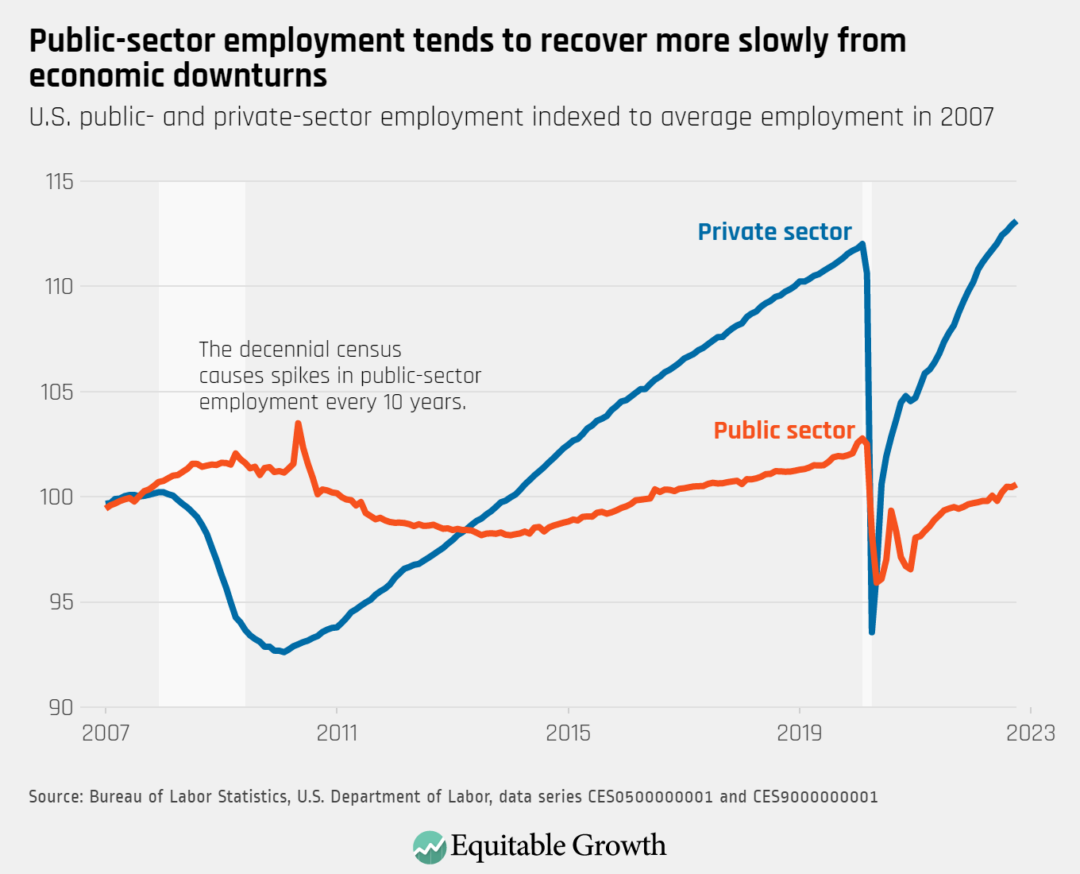

Public sector employment still lags in the recovery, with private sector employment above its pre-pandemic levels.

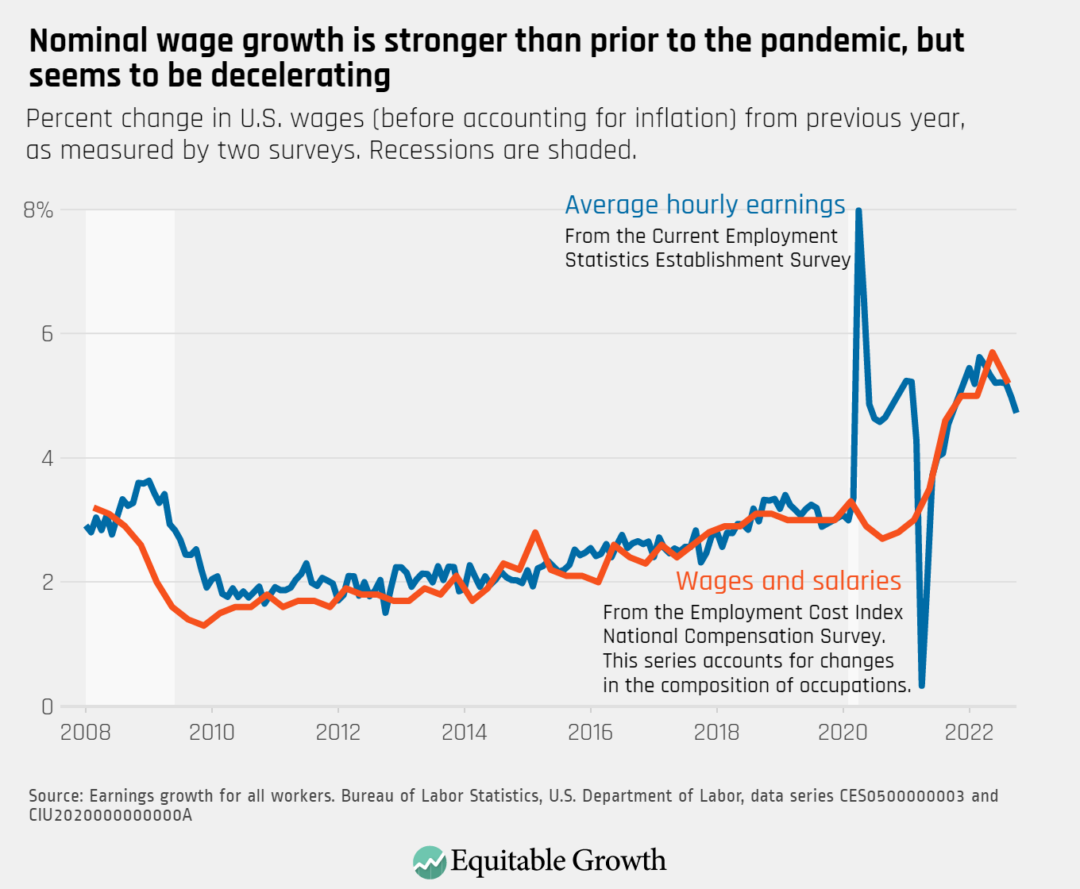

Wage growth decelerated in October, further demonstrating a lack of evidence that wage pressure is a primary cause of continuing inflation

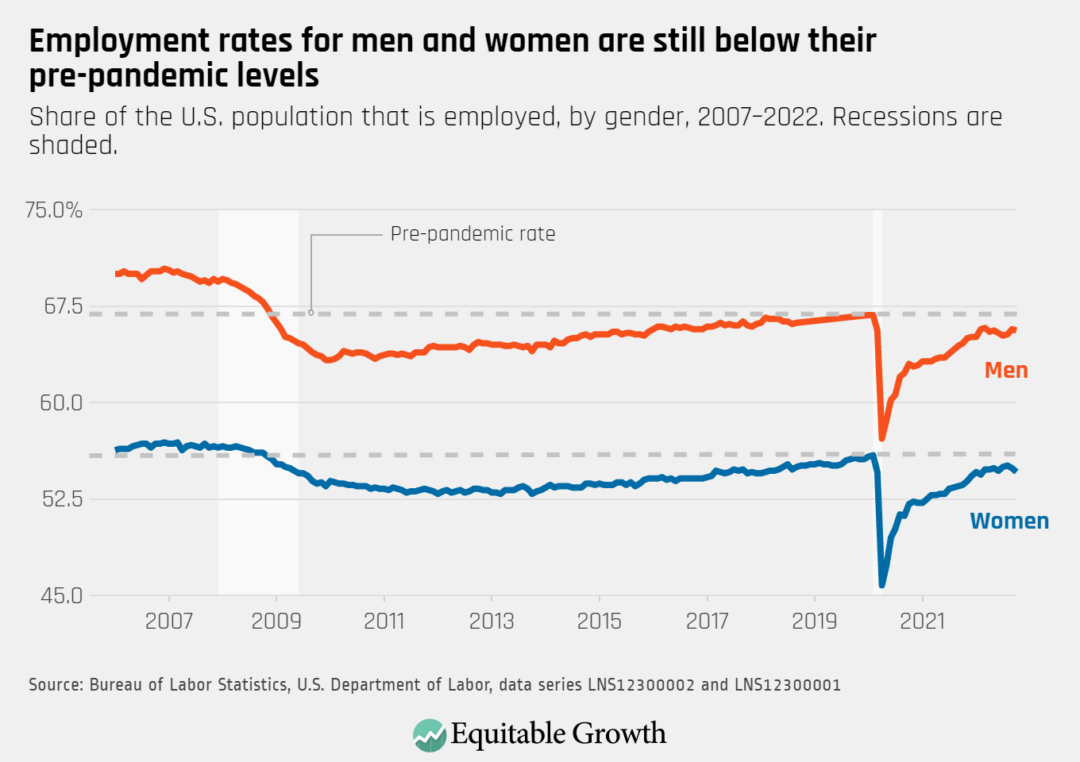

Employment rates decreased for women and men in October, but slightly more so for women as unemployment levels increased and almost 200,000 dropped out of the labor force.

The Fed is aggressively but perhaps deliberately playing catch-up on inflation

While there are legitimate fears that these rate hikes are coming too fast, even risking a recession, a recovery with higher inflation should not be surprising in the context of the full response to the COVID-19 recession of 2020. A key question going forward is whether the Fed could be playing catch up on inflation now as a necessary consequence of using a well-studied monetary policy response to recessions that occur when inflation and interest rates are very low.

Importantly, key research on monetary policy discussed in this column contextualizes current above-target inflation. This research suggests that the Fed was neither unable nor late to react to inflation, but was constrained by policy compromises required when inflation and interest rates are too low entering a crisis.

The Fed reacted slowly to the inflation reversal that began in October 2021, but its policy has followed a thin playbook for setting rates amid economic uncertainty and the legacy of very low interest rates over the past decade. The combination of low real interest rates (after accounting for inflation) amid the low inflationary environment that persisted for the decade prior to 2021 gave the Fed few options to respond to the negative shock of the COVID-19 pandemic beginning in 2020 and the subsequent short but extremely sharp recession that year.

After all, cutting rates by 5 percentage points or more, as in previous recessions, would have required strongly negative interest rates. The Fed’s monetary policy response to the COVID-19 recession of 2020 instead was to cut policy interest rates to zero, commit to holding rates low in the future (forward guidance, in central bank jargon), and keep a host of financial markets from seizing up. But 2022 has underscored the more subtle challenge that using the stimulus tools of a low real interest rate environment dictated that the Fed had fewer options to respond if inflation suddenly took off.

The Fed’s policy choices going forward will hinge on both how quickly inflation and so-called neutral real interest rates—rates that neither depress job growth nor stimulate inflation—fall and how quickly the new normal for each can be spotted. If the Fed can successfully communicate that it is following the research, there is little reason that interest rates need to keep increasing quickly, especially if inflation begins to peak in the coming year or so.

This column briefly examines recent U.S. monetary policy history, offers up some research that has been little-discussed that may already be very influential to the Federal Open Market Committee, and offers some lessons perhaps to be learned in the process by monetary policy researchers and policymakers alike.

Was the Fed slow to respond or practicing deliberate monetary policy?

As recently as the third quarter of 2021, U.S. COVID-19 cases and inflation were in steady decline, with the Fed’s preferred core Personal Consumption Expenditure measure of inflation nearing the central bank’s 2 percent target. More importantly, little evidence of a long-term shift in inflation was apparent. What followed was 12 months of high and volatile inflation readings that were not predicted by markets or the Fed. So, after months of waiting, the Fed acted aggressively in May 2022.

This slow-then-aggressive path of rate hikes drew outsized attention to arguments that the Fed was “behind the curve.” Yet this pattern of rate hikes follows directly from well-established monetary policy scholarship. Two key insights from this literature that are often missing from the discussion are:

- Monetary policy should rely on simpler rules and focus more on inflation than unemployment when monetary policy uncertainty is high.

- Monetary policy should respond more slowly and with more inertia when nominal interest rates start from low levels and monetary policy uncertainty is high.

Restraining from hiking rates in the early phases of inflation and reacting more aggressively once the emergence of inflation is more clear can be a prudent strategy when interest rates are close to zero. That is exactly where the Fed found itself over the past 18 months, but it can be difficult to identify this pattern looking backward.

The logic behind this policy is relatively straightforward. Because cash and other financial instruments blunt negative interest rates’ effectiveness, central banks face asymmetric risks when nominal interest rates are near zero.

Additionally, standard monetary policy rules, which the Fed uses as a guide to set interest rates, are defined assuming an inflation target and knowledge of steady-state unemployment and interest rates. When the steady states of unemployment and interest are ambiguous, the Fed can do better by instead moving interest rates in response to changes in inflation—a measure it can observe directly—rather than focusing on gaps between equilibrium interest rates and employment rates that depend on these estimated parameters.

In this framework, the past decade of nominal interest rates at or barely above zero makes the case for a slower-then-faster reaction to inflation—slowing the economy in 2021 risked recession and deflation. But, following the same literature, the Fed’s aggressive moves in the second half of 2022 are a consequence of the need to respond slowly to ambiguous signs of inflation in late 2021 and stronger signals of inflation in 2022.

Importantly, this response is not solely the result of low nominal interest rates, but the result of factors beyond the Fed’s control—low natural interest rates, which are essentially where the Fed is forced to set interest rates by long-run economic forces—and factors the Fed does control, namely its inflation target.

The monetary policy research upon which policymakers may well be relying

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, monetary policy research focused on sustained low inflation for the first time in generations and focused extensively on how the Fed should conduct monetary policy with low interest rates and amid uncertainty—precisely the state of the U.S. economy the Fed has faced since the pandemic. Among those researchers was John C. Williams, now head of the New York Fed and a vice chair of the Federal Open Market Committee, and not the only FOMC member to publish in this area.

Unfortunately, even as steadily declining U.S. unemployment and volatile inflation has validated the Fed’s use of tools from a relatively thin applicable playbook, some commentary questions the Fed’s credibility. Faced with pressure to retain credibility, the Fed has been hawkish in action and in communications for the past 6 months, and market measures suggest this has kept medium-term expectations closely in line with its 2 percent target rate of inflation.

The Fed may be strategically loathe to show too many cards, but Fed communications could have better foreshadowed its rate-hike path. Yet the good news is that as the need for catch-up rate hikes declines, so too does the downside to communicating this approach. Recent comments from FOMC members on possible pauses in rate hikes suggest the rate-hike path is following the catch-up trajectory prescribed by the near-zero and uncertain rates literature.

The value of racial and gender diversity at the Federal Reserve

September 16, 2021

In Conversation with Atif Mian

January 14, 2019

Lessons for setting future monetary policy

This spurt of inflation is not over, but even as it shows signs of easing in the coming year, the past 2 years present a challenge for the Fed’s policy framework and longer-term inflation targets. The political costs of high inflation to the Fed have been significant, suggesting that low inflation not only raises risks of deflation in the event of negative shocks, but also makes defeating inflationary episodes more politically costly for monetary policymakers than previously appreciated.

There are Fed credibility issues with moving to a higher inflation target without first reaching the 2 percent goal. Nonetheless, the inflation required to deal with the pandemic shock from a low interest rate baseline has left the case for moving beyond the 2 percent inflation target framework stronger now than it was before the COVID-19 pandemic and recession.

It’s too early for the Fed to discuss long-term strategy, but it’s not too soon for researchers and policymakers alike to begin improving on a framework that was delivering weak economic growth and rising inequality for a decade before the latest crisis.

JOLTS Day Graphs: September 2022 Edition

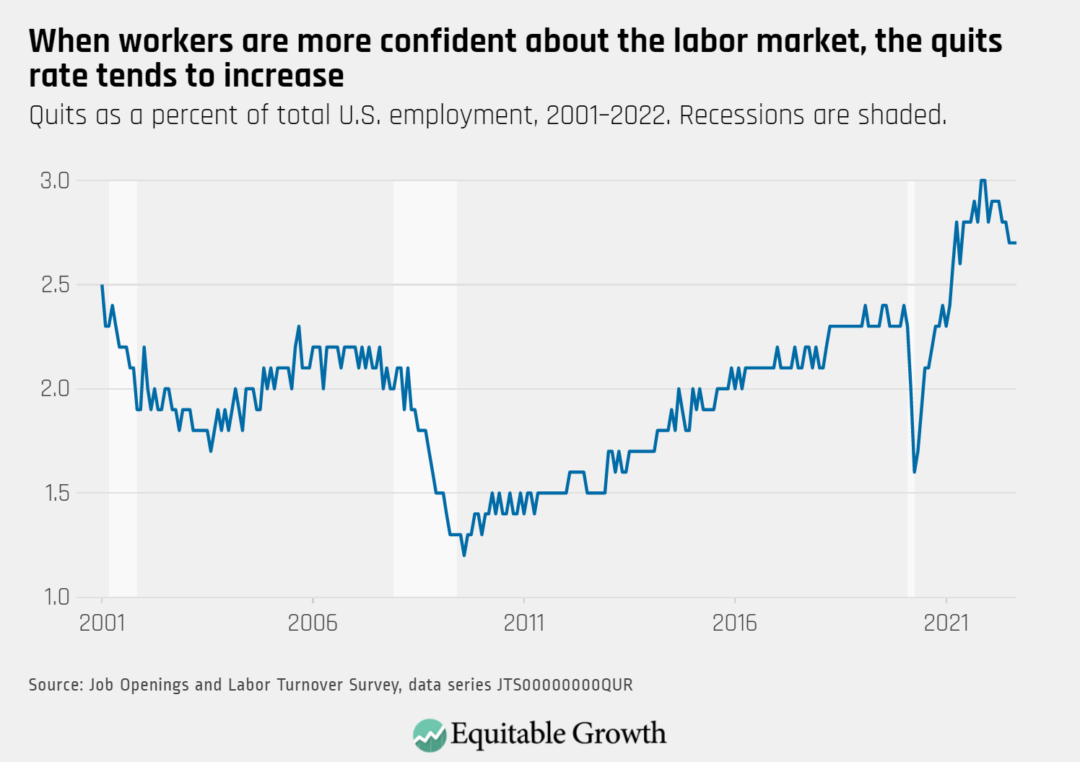

The quits rate remained steady at 2.7 percent as 4.1 million workers quit their jobs in September 2022.

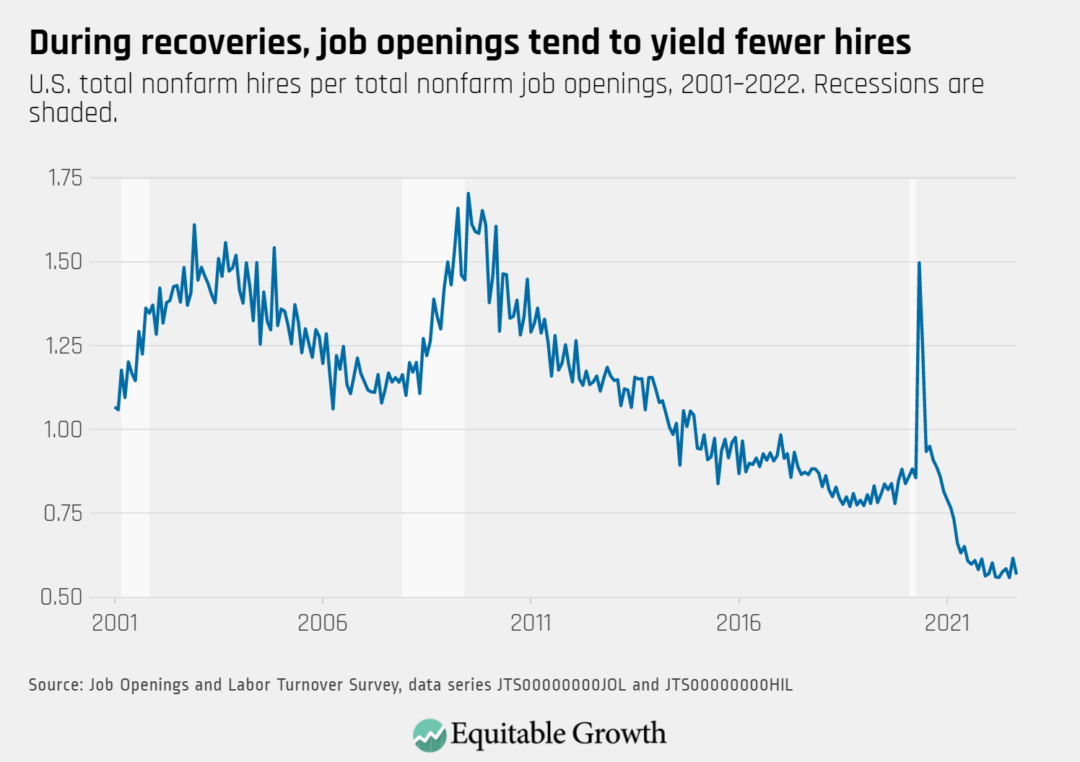

The vacancy yield declined to 0.57 in September from almost 0.62 in August, as job openings rose to 10.7 million and hires decreased to 6.1 million.

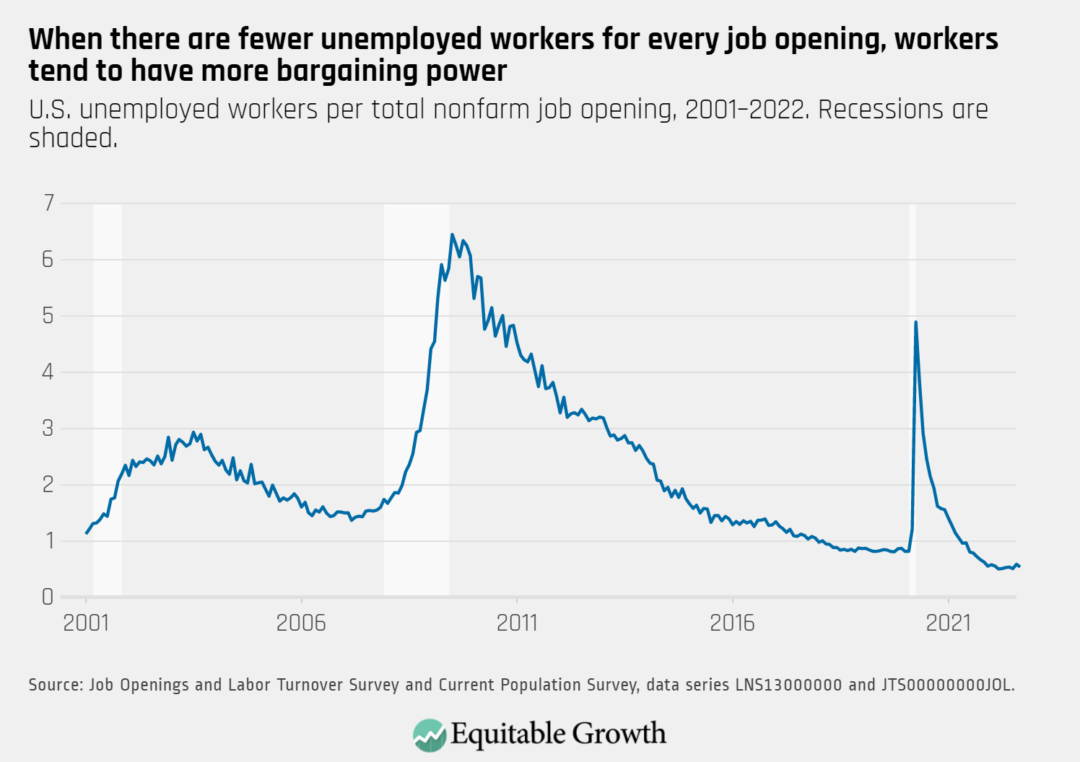

The ratio of unemployed workers to job openings decreased to almost 0.54 in September from just less than 0.59 in August.

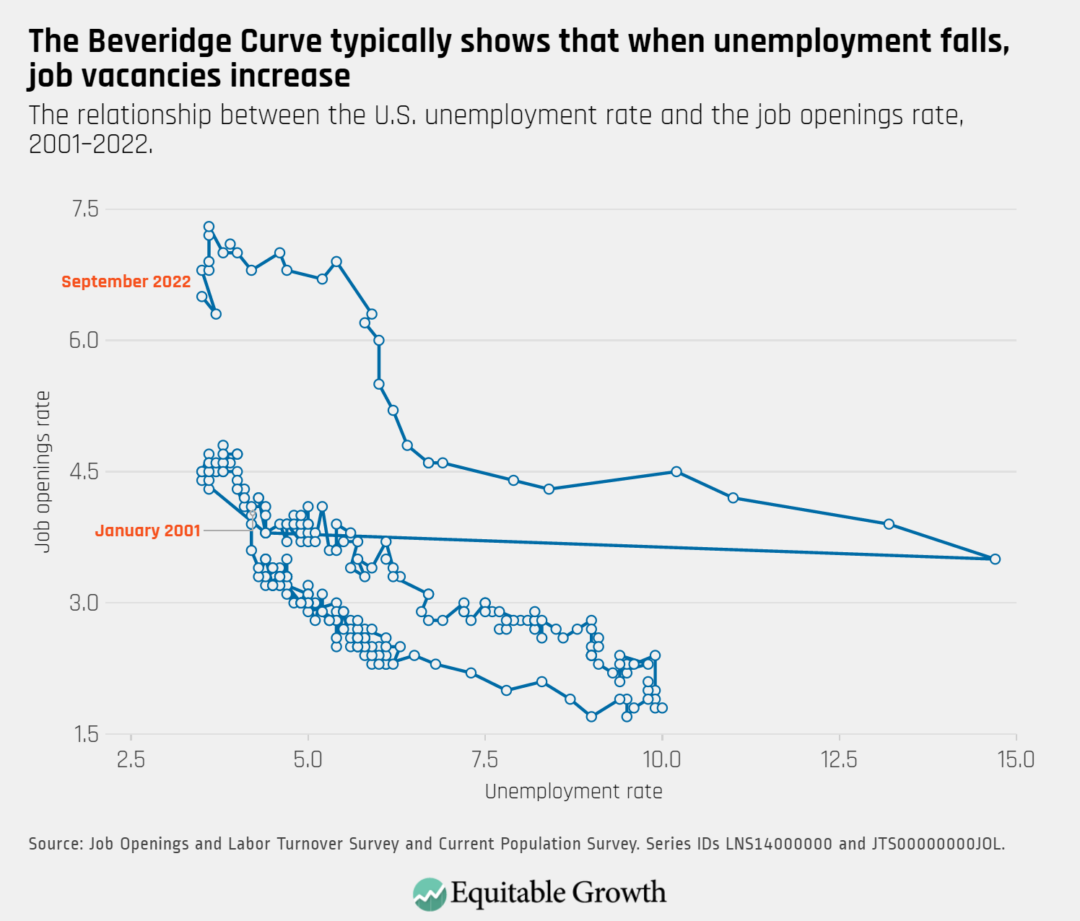

The Beveridge Curve moved upward in September as reported job openings rose and as the unemployment rate ticked down.

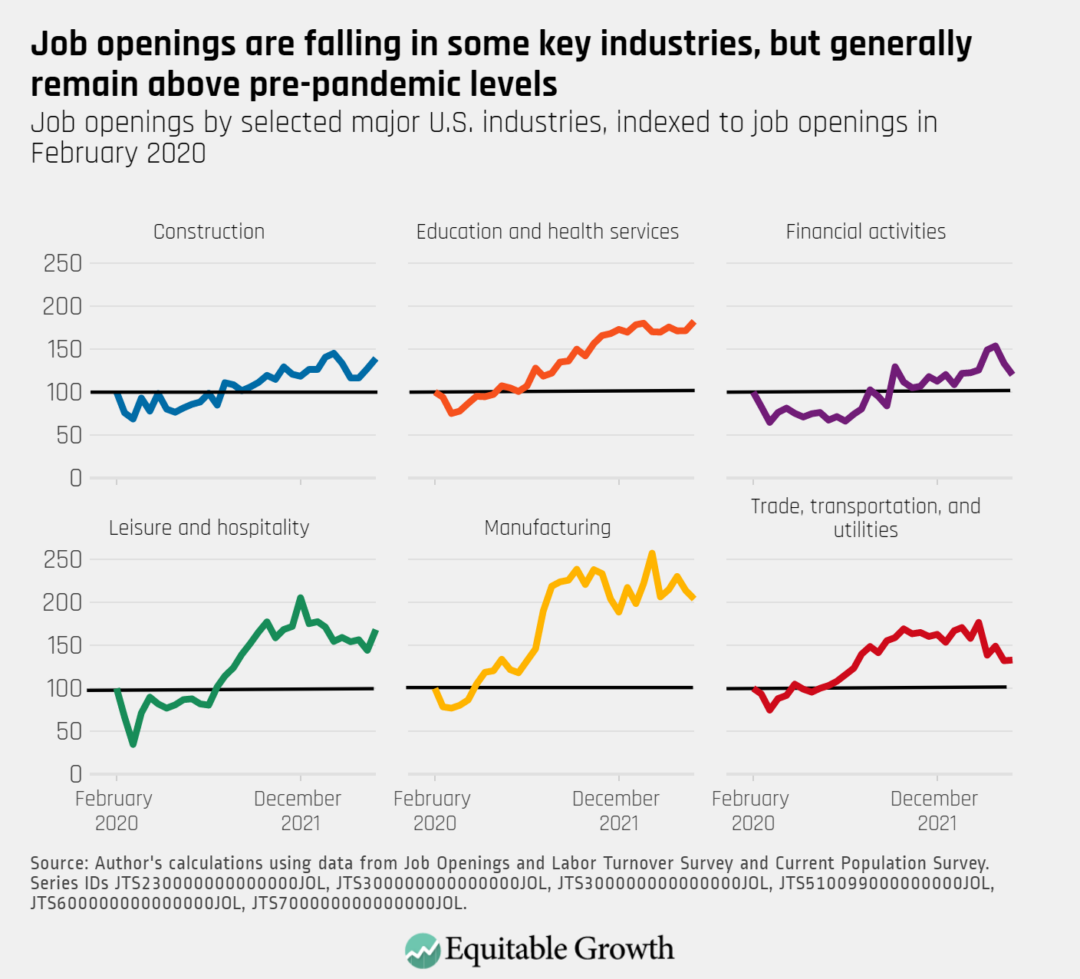

The overall number of reported job openings increased by 437,000 in September, with openings rising in construction, education and health services, and leisure and hospitality, but falling in financial activities and manufacturing.

Expert Focus: Researchers advancing our understanding of U.S. child care policy and how to improve the early care and education system

Equitable Growth is committed to building a community of scholars working to understand how inequality affects broadly shared growth and stability. To that end, we have created the series “Expert Focus.” This series highlights scholars in the Equitable Growth network and beyond who are at the frontier of social science research. We encourage you to learn more about both the researchers featured below and our broader network of experts. If you are looking for support to investigate the U.S. child care policy and the early care and education system, please see our funding opportunities and stay tuned for our next Request for Proposals in November 2022.

Child care and early education underpins the U.S. labor force and the overall economy. Yet broad investment in U.S. social infrastructure, including in child care, is often overlooked as a contributor to creating a strong, stable, equitable, and prosperous labor force and economy. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, many early care and education providers closed their doors and schooling became virtual, forcing millions of workers—many of them women and mothers—to stretch themselves thin balancing child care and work or even to leave the workforce entirely.

Child care workers also are severely underpaid and have one of the highest turnover rates in the U.S. labor market, leading to unstable and inadequate care environments for many children and a dearth of quality, affordable providers for many others. Despite these challenges—all of which were exposed and worsened by the pandemic—policymakers have, year after year, failed to make the necessary public investments in early care and education and its workforce.

There is a broad base of evidence showing the importance of these investments and how they more than pay for themselves by boosting economic growth in both the short and long term. U.S. child care policy remains inadequate for how vital this industry is to the functioning of the overall economy. Research shows that the U.S. child care sector remains woefully unprepared to navigate future economic downturns and is on the brink of a potential crisis.

This month’s Expert Focus highlights scholars whose research will help inform U.S. early education and child care policy. The body of work put out by these and other early childhood experts shows that policy interventions will not only offer much-needed support to the child care workforce, but also strengthen family economic security and well-being, improve children’s future economic and health outcomes, and boost the broader U.S. economy.

Lea Austin

Center for the Study of Child Care Employment

Lea J.E. Austin is the executive director of the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment at the University of California, Berkeley, where she leads the center’s work to ensure the well-being of U.S. early educators. She is an expert on the U.S. early care and education system and its workforce, and has extensive research experience in the areas of compensation, preparation, working conditions, and racial equity in the child care sector. Recently, she has explored the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the child care sector and early care workforce, finding that preexisting disparities and challenges in the industry were deeply exacerbated by the economic and public health crises.

Jessica Brown

University of South Carolina

Jessica H. Brown is an assistant professor of economics at the University of South Carolina’s Darla Moore School of Business. Her primary research interests are in public and labor economics and the economics of the child care market. Her recent co-authored research looks into the impact of increased public investment in early childhood education, finding, for instance, that subsidizing families’ child care payments would increase mothers’ employment by 6 percentage points and full-time employment by around 10 percentage points, with most increases occurring among low-income families. Another recent paper, co-authored with Chris Herbst of Arizona State University, examines the effects of macroeconomic cycles on the child care industry, finding that child care employment requires more time than other low-wage industries to recover from downturns. Her investigations into how the child care market responds to early care and education policy change have helped inform policymakers and advocates in crafting policy solutions that promote the stability of the entire early care and education market.

William Gormley

Georgetown University

William T. Gormley is university professor and professor of government and public policy at Georgetown University, as well as the co-director of the university’s Center for Research on Children in the United States. For nearly two decades, Gormley has worked to shape early childhood education and child care policy. His extensive work on the Tulsa preschool project—which began in 2001 to track the effects of Oklahoma’s universal pre-Kindergarten program—has been covered by many popular media outlets and academic journals. He also has recently written on universal pre-K and how to make it work in the U.S. context, analyzing President Joe Biden’s calls on Congress in 2021 to pass a nationwide public preschool program.

Julia Henly

University of Chicago

Julia R. Henly is a professor in the Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy, and Practice at the University of Chicago, where she also serves as deputy dean for research and faculty development. Her research interests lie in the economic and caregiving strategies of low-income families and the design, implementation, and effectiveness of employment and child care policy and programs. Her ongoing projects include investigations into how COVID-19 impacted center- and home-based child care programs, equity in child care subsidy access and the effects of recent subsidy policy changes on program participation, child care decision-making of low-income families who use child care subsidies and families seeking care in Latino communities, and the effects of work schedule precarity and workplace flexibility on worker and family well-being. In 2021, Henly was awarded an Equitable Growth grant with David Alexander of Illinois Action for Children to further her work on child care subsidies and the home-based child care sector, particularly amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Taryn Morrissey

American University

Taryn Morrissey is a professor in the Department of Public Administration and Policy at American University. In the spring and summer of 2022, she was on leave from her faculty position to work at the Office of Child Care at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Her research focuses on public policies for children and families, including early care and education, nutrition and income assistance, and paid family leave, as well as family economic instability. Recent co-authored research includes a paper that looks into the connection between parent economic stability and the stability of children’s child care subsidy receipt, as well as another paper on access to early care and education in rural communities. In 2020, Morrissey contributed a chapter to Vision 2020: Evidence for a stronger economy, a compilation of 21 essays to shape the policy debate published by Equitable Growth. Her essay examined the need for affordable, high-quality, and universal early care and education in the United States.

Corey Shdaimah

University of Maryland, Baltimore

Corey Shdaimah is the Daniel Thursz Distinguished Professor of Social Justice at the University of Maryland School of Social Work. Her research focuses on the policy implications of child care, dependency court, and street-based sex work. Recent media appearances focus on the U.S. child care sector, including the failure to support families and providers who bear care responsibilities. In 2021, she received an Equitable Growth grant, alongside Bweikia Steen of George Mason University and Elizabeth Palley of Adelphi University, to study the various challenges facing informal, home-based child care providers in the United States—a relatively unstudied group. She is also the co-author, with Palley, of In Our Hands: The Struggle for U.S. Child Care Policy (NYU Press, 2017), a book that explores why there hasn’t been much policy action to improve the U.S. child care industry.

Equitable Growth is building a network of experts across disciplines and at various stages in their career who can exchange ideas and ensure that research on inequality and broadly shared growth is relevant, accessible, and informative to both the policymaking process and future research agendas. Explore the ways you can connect with our network or take advantage of the support we offer here.

What federal statistical agencies can do to improve survey response rates among Hispanic communities in the United States

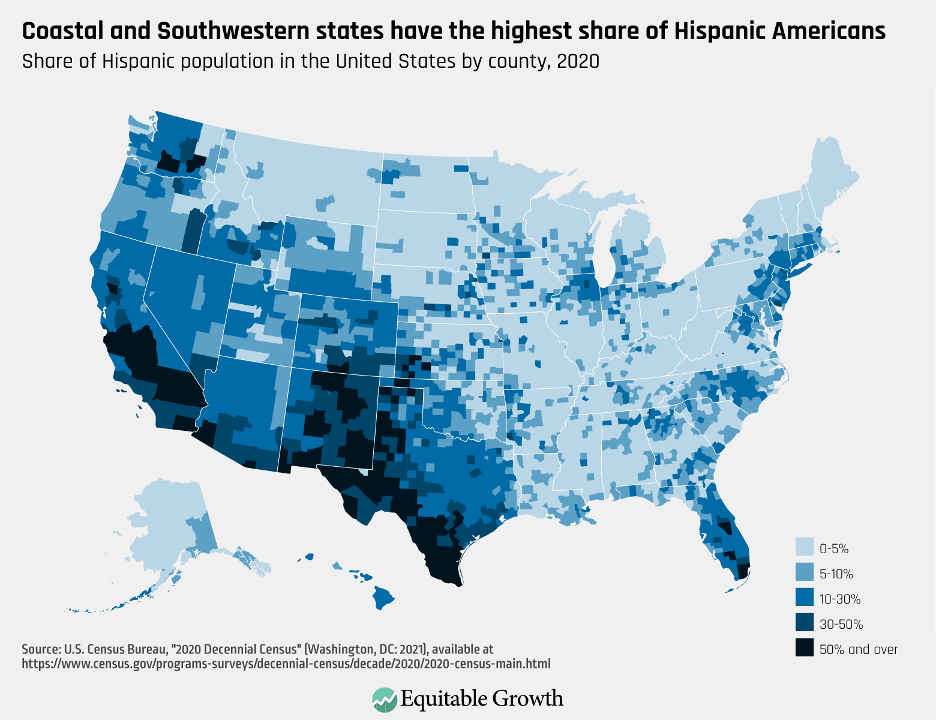

Between 2010 and 2020, the Hispanic American population grew 23 percent, making it one of the fastest-growing communities in the United States. According to the 2020 decennial census, Hispanic Americans make up 20 percent of the total U.S. population. Figure 1 shows the geographic distribution of Hispanic Americans by county in the 2020 decennial census.

Figure 1

Disaggregating economic and social data by race and ethnicity allows researchers to better understand the socioeconomic well-being of Hispanic communities and other communities and their key contributions to U.S. economic growth, allowing policymakers to create legislation and regulations that tackle the issues these specific communities face.

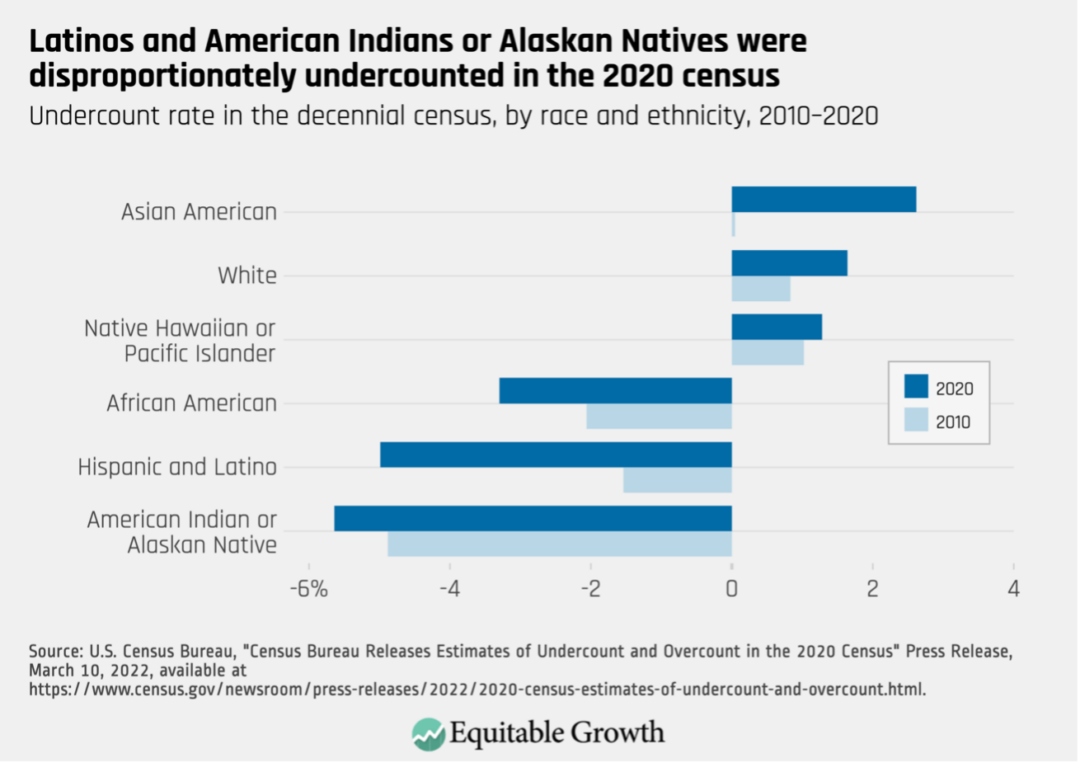

Yet studies show that Hispanic Americans have a lower response rate to federal surveys than other racial and ethnic groups. In the most recent decennial census, for example, survey collectors reported that Hispanic Americans had the second-highest undercount rate of all racial or ethnic groups after American Indians and Alaska Natives. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Approximately 1 out of every 20 members of the Hispanic community was not counted in the most recent census in 2020. That undercount will impact the creation of local and federal voting districts and the allocation of federal funds for community development in Hispanic-populated regions.

This is not a new issue for the U.S. Census Bureau, and the agency is open to new ways of counting non-White populations. The Census Bureau first began collecting data on Hispanic communities in the 1930 decennial census by including “Mexican” as an option to the race/ethnicity question. Federal data collection has come a long way since then in providing a more inclusive list of race and ethnicity options from which respondents can choose.

The most recent census in 2020 includes options for Hispanic respondents to indicate their country of origin. Adding inclusive race and ethnicity options in surveys is important, but survey collection is only successful if enough members of the population respond to these surveys.

As mentioned above, recent analysis indicates that members of Hispanic communities have a lower response rate to federal surveys than other race or ethnic groups. There are many reasons for the discrepancy in the response rates, but researchers identify three potential causes that have a significant impact on response rates:

- Distrust of government

- Language barriers related to data collection

- Lack of inclusive race and identity options in survey questions

In this column, I briefly survey the current research on each of these three factors. Resolving these discrepancies in response rates will enable policymakers to better understand how economic inequality may be affecting Hispanic communities and enable them to design policies that create more equitable—and thus stronger and more sustainable—economic growth.

Government distrust

Hesitancy in responding to surveys often stems from a general distrust of government or fear of deportation even among those who are legally residing in the country, often because respondents residing legally in the country live with or are related to undocumented immigrants. Federal law states that federal statistical agencies can only use data collected in federal surveys for statistical purposes. In other words, sensitive information from these surveys cannot be shared with other agencies and cannot be used to identify individuals within specific populations.

Yet with the rise in hateful rhetoric about immigrants, often from elected officials, many members of Hispanic communities say they can’t trust the government to protect them, even if their health and safety is at risk. In a recent survey on public trust, only 29 percent of Hispanic respondents said they trust the government in 2022, as opposed to 57 percent of Hispanics in 1998.

These efforts to spur distrust in federal statistical gathering are often calculated. When the Trump administration attempted to include a citizenship question on the 2020 census, for example, Latino advocacy organizations understandably opposed it because they feared it would deter immigrants from responding, leading to an inaccurate count. Importantly, the U.S. Constitution requires that a decennial census be collected on all people living in the United States—not all citizens, which is why a citizenship question was removed from the 1950 census.

The U.S. Supreme Court eventually ruled that the 2020 census would not contain a citizenship question. But the damage was already done: The National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials Educational Fund reported that even after the Supreme Court’s ruling, members of Hispanic communities were hesitant to fill out the survey over fears of a citizenship question.

Despite statistical agencies reassuring respondents that information collected in federal surveys is kept confidential, one Census Bureau study found that 31 percent of Hispanic respondents “were ‘extremely concerned’ or ‘very concerned’ that the Census Bureau would share their answers with other government agencies,” and 34 percent of respondents who answered the survey in Spanish said that they feared that their answers would be used against them. This general distrust in government is present in other demographic groups, but it particularly hurt Hispanic communities in the 2020 decennial census.

In 2015, surveys such as the decennial census and the American Community Survey were used to determine how 132 federal programs distributed almost $700 billion in federal funding. A misestimation of the disaggregated composition of the U.S. population means that this vital funding could ignore thousands of vulnerable households among historically marginalized communities.

Rebuilding trust in government is the first step in improving survey response rates for Hispanic communities. In a series of focus groups of Census Bureau field representatives and supervisors, these representatives indicated that some Spanish-speaking survey respondents were hesitant to complete surveys if they were required to share personal information on surveys. But when they were encouraged to provide fake names, they acquiesced.

Field respondents and the Center for Survey Management consequently recommended that in order to erase some of the distrust in federal surveys, survey questionnaires should include language at the start that ensures anonymity and security of data. Additionally, they recommended that field respondents who go door to door collecting survey data receive training on how to interact with communities who fear government, including clearly identifying themselves as not immigration officers.

Emphasizing the importance of completing surveys for the benefit of individual communities can help erase the distrust component for the sizable survey nonresponse rates among Hispanic populations. In a private study on recruiting Hispanic and Latino survey respondents, the report’s authors indicated that in addition to explicitly stating the privacy measures agencies intend to take to protect individuals’ identities, survey administrators should emphasize the impact that participation may have on respondents’ communities. Stressing the effects that federal survey results have on disproportionately affected communities can inspire individuals to complete surveys in the name of community improvement.

Additionally, a 2015 study of survey response patterns among African Americans and Latinos found that respondents were more likely to participate in and complete a survey if they learned about it though members or agencies within their communities. As such, the Census Bureau partnered with numerous community organizations to try to spread the word about the importance of completing the 2020 census. Going forward, broadening these partnerships for the next census and applying this approach to other federal survey outreach plans, such as those for the American Community Survey and the Current Population Survey, can improve the quality of data collected on the economic and societal well-being of vulnerable populations.

Language barriers and collection methods

After English, Spanish is the most-commonly spoken language in the United States, with more than 42 million people in the country speaking Spanish in their homes. The federal statistical agencies know that to capture an accurate representation of the U.S. population, they need to provide bilingual survey options, especially in Hispanic-populated areas.

The 2020 census was offered in 12 languages besides English. In addition to making it possible for non-English speakers to respond to federal surveys, this practice opens up possibilities for more disaggregated analysis of the U.S. population. The Census Bureau found, for example, that respondents to the Census’ Household Pulse Survey Spanish questionnaire reported double the rates of food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic than Hispanic-identifying respondents who took the English version of the survey. This discrepancy could be the result of Spanish-only speakers or those with limited English language proficiency facing economic, social, and health barriers when navigating U.S. institutions and communities that largely favor English.

Bilingual questionnaires are common practice today, but some researchers argue that the existing structures of the administration of bilingual verbal surveys might fail to accurately capture more accurate data. In their National Survey of Latinos, for example, the Pew Research Center conducted over-the-phone surveys using two methods: a fully bilingual method in which interviewers were prepared to collect respondent’s data in either English or Spanish, and a modified bilingual method in which interviewers only spoke English. In this latter method, if interviewers encountered a respondent who preferred to answer the survey only in Spanish, then they would inform respondents that they would instead receive a call from a Spanish-speaking interviewer.

The Pew study found that more interviews with Spanish-language-dominant respondents were conducted with the fully bilingual method over the modified bilingual method. The Census Bureau has already taken steps to ensure the decennial census in 2030 maintains the fully bilingual method for phone interviews. Applying this methodology to all federal surveys, including the American Community Survey and the Current Population Survey, could ensure better-quality information on various communities as a whole.

Noninclusive race and identity options

Confusion over how to identify one’s race and ethnicity has led to inconsistencies in data collection among Hispanic communities. According to the federal government, “Hispanic” is an ethnicity to identify people “of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin regardless of race.”

To help respondents identify themselves within this definition, the federal government, over the past decade, has established a two-question structure for asking respondents about their race and ethnicity: They first ask if respondents are Hispanic or Not Hispanic to determine ethnicity and then ask what race they identify themselves as, with the choices of White, Black, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, two or more of these choices, or Other.

Not surprisingly, this type of question structure can cause confusion for those who may consider “Hispanic” to be a race rather than an ethnicity or who don’t identify with the provided race options. In an analysis of the 2010 census, researchers found that 13 percent of respondents who selected “Hispanic” in the ethnicity question left the race question blank, and another 30 percent of such respondents wrote in “Hispanic” for the race question.

Furthermore, a 2015 Pew Research study found that different respondents have very different impressions of what these questions are asking. Their polling found that 42 percent of Hispanic adults consider “Hispanic” to be a matter of one’s culture, while 29 percent said that it was a matter of ancestry and another 17 percent said it was a matter of race.

Results from the 2020 census show that Hispanic respondents primarily identified as being “Some other race” or “White,” yet previous test surveys conducted in advance of the 2010 census found that most Hispanic respondents who selected “White” as their race did not actually identify as White but did so in order to complete the survey. When Hispanics select “Some other race,” they are putting themselves in a category that also includes Middle Eastern and North African respondents and many others.

In fact, “Some other race” is now the second-most frequently selected category on the Census after “White.” The category has become so large, it has little analytical value, and its catch-all quality is obscuring the true number of Hispanics in the United States.

In order to dispel confusion surrounding race and ethnicity and improve the accuracy of self-reported race statistics, federal statistical agencies have been experimenting with the structure of this question. In 2016, the Census Bureau studied what the effects a combined race and ethnicity question would have on survey responses. This structure added “Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin” to the list of previously designated races and asked respondents to write out their origin.

The results indicate that this structure not only made it easier for Hispanic respondents to accurately self-identify their race and ethnicity, but also improved the accuracy of those who identified as Hispanic and another race category. Under this new structure, for example, someone who identified as Hispanic and Dominican would be able to identify as such, rather than Hispanic and “Some other race.”

Demographic experts suggest that adopting this approach to federal survey collection, not just in the decennial census but also across all federal surveys, would reduce the share of Hispanic respondents identifying as “Some other race” and could improve Hispanic undersampling rates.

Conclusion

Fixing the nonresponse problem in the collection of federal survey data is not easy. It requires federal survey administrators to assess the causes in each community and be attentive to building public trust, breaking down language barriers, and establishing more-inclusive identity questions. In their efforts to improve response rates among the Hispanic community in advance of the 2030 decennial census and other federal data collection efforts, federal statistical agencies should revisit current practices to ensure they are leveraging the newest research on factors that influence response rates for Latinos and other ethnicities.

Incorporating this approach can lead to improved representation of Hispanic and Latino communities, better funding for programs vital to these communities, and a greater sense of inclusivity among all demographic groups in America. The resulting data would enable U.S. policymakers to produce more equitable economic policies that, in turn, drive stronger and more sustainable U.S. economic growth.