Policymakers tackling inflation can’t overlook the impact of higher interest rates on the U.S. child care market

As families in the United States grapple with rising prices and ongoing supply shortages, fiscal and monetary policymakers are shifting their focus from the COVID-19 recession and recovery to the ongoing issue of inflation. Headline inflation was 8.5 percent in July 2022—cooling slightly from earlier in the year—while core inflation, which excludes volatile energy and food prices, neared 6 percent.

While policymakers and economists are in the middle of a heated debate on the efficacy, relative dangers, and potential benefits of interest rate increases to address inflation, less attention is being paid to the sector-specific impacts of interest rate hikes and a subsequently cooling labor market. One particularly overlooked sector is child care, which has yet to fully recover from the COVID-19 recession and remains particularly exposed to the ebbs and flows of the macroeconomy.

As the Federal Reserve Board’s Federal Open Market Committee considers further rate increases in the coming months, it should weigh the potential impact on the child care sector, which underpins much of the rest of the U.S. economy and, as such, the country’s ability to achieve broad-based economic growth. Meanwhile, policymakers who control fiscal policy should make targeted, public investments in the stability of child care to minimize the damage that potential rate hikes could inflict on an already-fragile market.

This column looks at the state of the child care industry in the United States, the impact of a recession on the weakened care economy, and the details of policy actions that policymakers can take to protect the industry from collapse—thus protecting the broader U.S. economy as well.

The strong overall U.S. labor market masks fragilities in the child care sector

In July 2022, the economy added 528,000 new jobs while the unemployment rate ticked down to 3.5 percent. While some at the Federal Reserve suggest the U.S. labor market is “strong enough” to handle higher interest rates, these topline numbers mask lingering weaknesses in certain sectors.

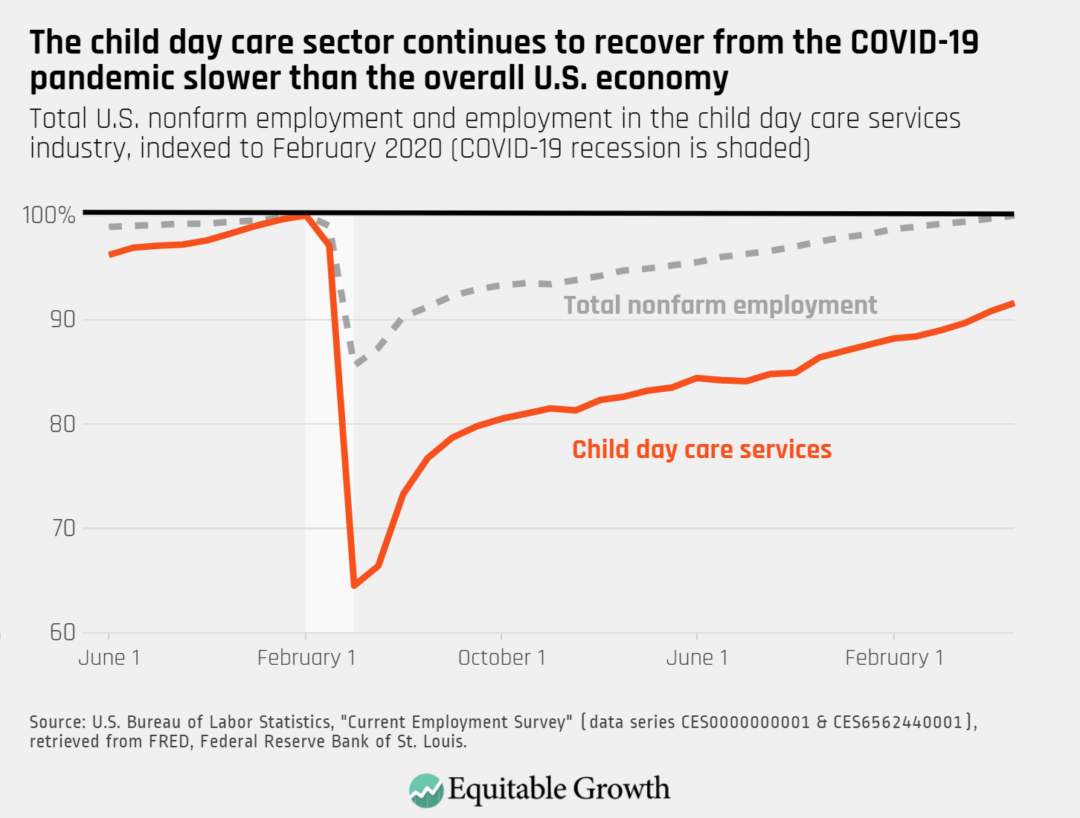

Despite a slight uptick in hiring this summer, child care is still missing more than 8 percent of pre-pandemic jobs, even as the rest of the private sector has completed its recovery. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Even prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the supply of child care could not meet the demand for care in most communities in the United States. While low unemployment in the broader economy provides the Federal Reserve some space to pump the breaks on the labor market—and, in turn, slow down wage growth and consumer demand—doing so while the child care sector is still lagging will only exacerbate the child care supply problem.

Employment in child care is depressed for two primary reasons. The pandemic forced many providers to exit the market. Data from Child Care Aware of America, a nonprofit organization for many child care resource and referral agencies, estimates that nearly 16,000 child care providers permanently closed between December 2019 and March 2021. But even the remaining providers are struggling to hire talent. The most likely reason is that wages in the sector have been too low to retain and recruit workers. Prior to the pandemic, real wages in the industry were falling, and in the current tight labor market, child care providers have struggled to compete on wages while keeping prices affordable for families.

Interest rate hikes may only exacerbate these problems. Decreasing the demand for labor and cooling the overall economy will likewise cool upward pressure on wages across the economy, which was just beginning to translate to higher salaries for child care staff. And by increasing the cost of borrowing and investing, the Federal Reserve also is making it more expensive for would-be child care providers to access the capital—for example, small business loans—they may need to open or re-open their businesses and expand the market.

Unprecedented fiscal investment in the broader economy during the COVID-19 crisis propelled a historically rapid employment recovery, yet those gains have not yet translated to the child care sector. To bring about a recovery in child care that parallels that of the broader economy, it is important to increase public investment—even more so if interest rates increase further.

In the absence of this investment and the presence of current rate hikes, the recovery for child care may mirror that of the public sector after the Great Recession of 2007–2009, which took more than a decade to recover its pre-recession employment levels following policymakers’ quick shift away from stimulus and toward austerity policies.

The child care sector, still recovering from the previous recession, may not survive the next one

The aggregate strengths of the current economy have emboldened policymakers to tackle inflation more aggressively, even as Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell acknowledges that a “soft landing”—in which inflation cools without significant harm to the economy—is far from guaranteed. Indeed, fears of a recession are growing among economists, even as other reliable indicators of recessions show it is not inevitable.

As discussed above, the U.S. child care sector is still in the midst of a delayed recovery from the COVID-19 recession. Slowing demand in the economy with interest rate increases could also cool demand for child care services. Since the child care sector is having trouble meeting current demand, some may say that a recession would provide some much-needed relief: Unemployed parents pull their children out of care, decreasing competition for limited slots and, potentially, lowering prices as well.

Yet this view is short-sighted. Reducing both the incentive and the resources for providers to hire staff and open new facilities will further exacerbate the nationwide child care supply crisis. Once the broader economy recovers, the child care sector will be in an even worse position than it is today.

While children always need care regardless of the state of the economy, the child care industry is not recession-proof. Reliance on parental fees leaves the child care market particularly exposed to broader economic trends. When parents are laid off, they often can no longer afford child care and may take their children out of care. Because profit margins for child care providers are so thin, if even just a few parents pull their children from care, then the provider may need to lay off staff—or even temporarily suspend operations entirely—to stay in the black. This makes care harder to find, especially for parents who remain employed and want to keep their children in care to be able to go to work.

It is true that demand for child care likely exceeds supply currently, but this may not ensure the market against the scenario described above. Indeed, demand for child care exceeding supply is not a new trend, and it has not served as a buffer against the rise and fall of the business cycle in the past.

Research by Jessica H. Brown from the University of South Carolina and Chris M. Herbst from Arizona State University, for example, demonstrates how this exposure to the macroeconomy has played out in periods of economic contraction in the decades prior to the COVID-19 pandemic: Every 1 percent decline in a state’s overall employment is associated with a 1.04 percent decline in child care employment, but every 1 percent increase in a state’s overall employment is only associated with a 0.75 percent increase in child care employment. Even when the economy is in recovery and newly employed parents wish to enroll their children back in care, there are inherent delays while the child care industry rebuilds capacity that was lost during weaker economic times.

Providers’ financial health also often depends on attracting the correct mix of clients based on subsidy status, age range, and even personal relationships. Profits made on preschool-age children, for example, are often used to subsidize the care of infants and toddlers, which is more expensive to administer. A decline in demand among a key group of clients could offset even excess demand among another group. Simply put, not all demand is of equal value to providers, and the uncertainty and instability that rising unemployment may pose is not something the struggling industry can easily afford.

Policymakers can take small steps to protect child care while tackling inflation

Inflation fears in Washington have contributed to a pared-down budget reconciliation package, an historic climate investment that will also provide an important boost for some areas of the U.S. economy but ultimately fails to provide the social infrastructure that the U.S. economy needs. A slimmed down child care reform proposal was not included in the final bill. While the American Rescue Plan did include much-needed flexible funding to stabilize the child care industry, these funds are beginning to run out, and the child care industry will soon be on its own.

Further public investment in care remains the first and best solution for revitalizing the child care market, increasing care workers’ wages and the quality of care, and lowering prices for families in the United States. These long-overdue investments would bolster economic growth in the short- and long-term by expanding parental employment and contributing to the human capital development of today’s children and tomorrow’s workers.

Inflation may have some key policymakers hesitant about engaging in necessary and overdue child care reform. Fortunately, policymakers still could make some tweaks to the U.S. child care system that would bolster supply, sustain demand, and protect the sector from a cooling economy—while still attempting to slow inflation. These tweaks would be nowhere near as impactful as robust, sustained public investment, but that should not stop policymakers from exploring interim solutions to strengthen the child care sector so it can withstand any rate increases that come along.

Ensure parents continue to receive child care subsidy payments throughout the business cycle

Subsidies through the federal Child Care Development Block Grant help fund child care services for millions of children across the country, but children can lose eligibility for these funds if their parents lose their jobs. During recessionary periods, this can lead to revenue losses and financial instability for child care providers. Because child care is such a low-profit and often-tenuous business model, even small fluctuations in revenue can threaten the overall stability of the sector.

Under current law, children are eligible for subsidies if their parents are engaged in one of three allowed activities: employment, school, or job training. Some states also consider looking for work an eligible activity, allowing parents the time they need to focus on their job search, though they can end subsidy payments if the parent has not found employment after 3 months.

Currently, there is bipartisan support in the U.S. Congress for expanding these allowable activities. Both the House-passed Build Back Better Act and the Child Care and Development Block Grant Reauthorization Act of 2022, which was introduced by Sens. Tim Scott (R-SC) and Richard Burr (R-NC), expand federal eligibility to subsidies for parents who are looking for work, self-employed, on Family and Medical Leave Act unpaid leave, or undergoing health treatment, among other work-limiting situations.

Adopting these expanded activities would ensure that all states consider job searching an eligible activity for child care subsidies, an important lifeline for both U.S. families and providers should rate hikes lead to a period of higher unemployment. Since research shows that the likelihood of long-term unemployment increases with the overall unemployment rate, policymakers and regulators should also consider automatically expanding subsidy access for job-searching parents beyond the minimum 3-month window during recessions or periods of high unemployment.

Without additional funding from Congress, such changes to the block grant eligibility requirements would do little to expand the overall number of families receiving subsidies. But such tweaks would still assist job-seekers in accessing the child care they need in order to conduct a successful job search and ensure continuity of revenue for child care providers during economic downturns.

Build and maintain the supply of care by providing low-cost capital

With the child care market still reeling from the COVID-19 recession, further economic contraction could shrink the already-depressed supply of care, making it harder for working parents to find the care they need to go to work and potentially raising the cost of care for those families lucky enough to find an available slot.

Policymakers must be proactive in ensuring that current and potential child care providers can access the capital they need to start a new business or keep their doors open. Access to such funds may take the form of startup and expansion grants for new and existing providers—both of which are included in the Build Back Better Act and the Scott-Burr Child Care and Development Block Grant Reauthorization Act mentioned above—as well as child care revitalization funds, similar to the existing Restaurant Revitalization Fund, to help existing providers offset ongoing financial losses from the COVID-19 recession.

Policymakers can also ensure access to low-interest or zero-interest loans though the U.S. Small Business Administration or similar entities, so that providers expanding their services can access cheaper capital even as the Federal Reserve raises interest rates. Indeed, there is currently bipartisan support for a policy change that would allow nonprofit child care providers to access more lucrative and flexible SBA loans that are currently reserved for their for-profit counterparts.

Additionally, policymakers can provide countercyclical and flexible Child Care and Development Block Grant funding so eligible providers can offset potential revenue losses during recessionary periods. Through the COVID-19 recession, Congress authorized flexible funds to stabilize the child care industry on several occasions, but many providers were forced to close before those funds were made available. Proactively allocating additional resources tied to economic conditions—following a model of automatic triggers—would ensure that these funds are available whenever the economy begins to contract.

While some policymakers are concerned that making these investments now would spur additional inflation, such grants and loans would be small relative to the overall U.S. economy. These should not meaningfully increase consumer demand or impact inflation, particularly when offset by other deficit reductions that Congress is considering.

Prioritize retaining and expanding the child care workforce through financial support

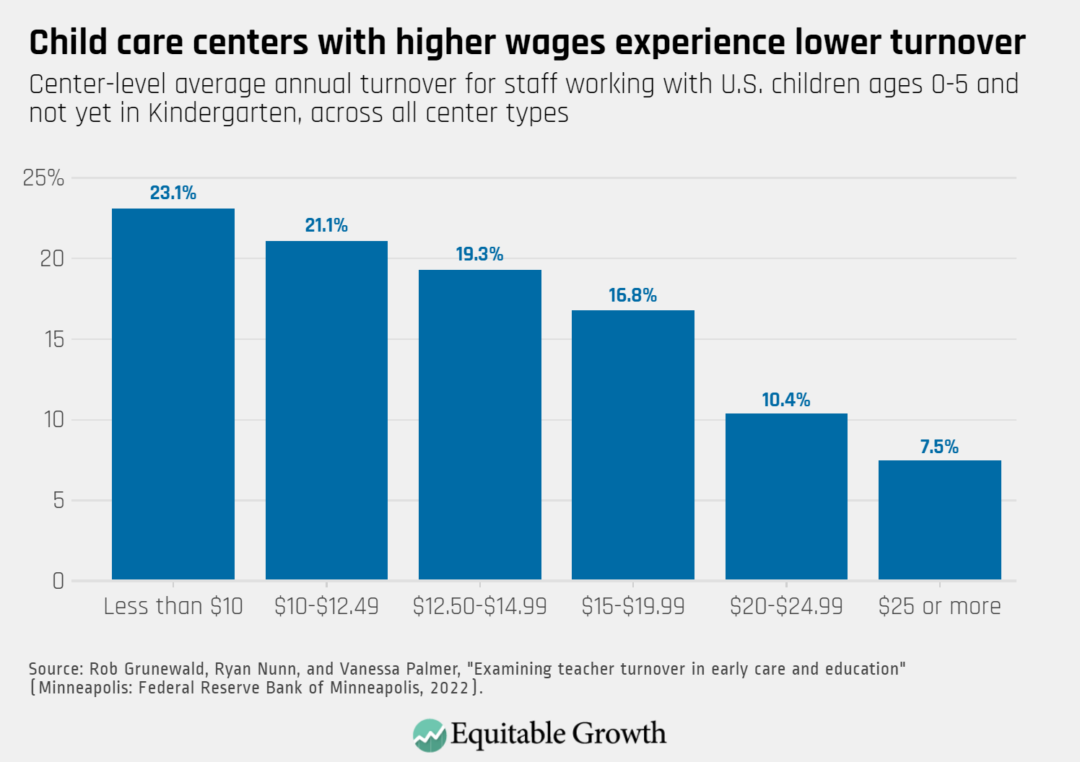

Low wages across the child care sector mean that many workers are paying an effective wage penalty for taking on this critical job. Low wages make it harder for child care providers to hire staff and contribute to costly turnover. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

To ensure that the child care sector continues to recover from the COVID-19 recession without backsliding during any potential interest-rate-hike-induced economic cooldown, policymakers must take steps to preserve the workforce and reduce the wage penalty associated with the profession.

For child care workers and early education providers with college degrees, expanding and clarifying eligibility for loan forgiveness programs, similar to the Teacher Loan Forgiveness Program, would entice new graduates to enter the field and discharge their loans after 5 years. For workers without a degree or loans, subsidized education and qualification programs could help keep workers connected to the sector and improve quality in the longer term. Because the economic gains to workers from such programs are realized across several years, such policies would minimally impact existing inflation.

At the state level, some jurisdictions have made one-time “recognition” payments to members of the child care workforce. Research from a 2019 pilot program in Virginia, for example, found that offering workers payments of just $1,500 if they stayed with their employer over an 8-month period halved turnover among teachers at child care centers. While sustained wage increases are desperately needed, these relatively low-cost payments can help reduce costly turnover for employers and bolster the supply of care across the market in the short term. States could use remaining American Rescue Plan funds to make such payments without requiring any additional new money, and because payments are modest and targeted to a specific subsection of workers, they are also unlikely to induce consumer demand and inflation to a meaningful degree.

Without stabilizing and expanding the supply of child care, families should expect to pay more for harder-to-find care or forgo child care services completely—and even their own employment as a result—to the detriment of their economic security and the overall health of the U.S. economy.

Conclusion

Following the COVID-19 recession and amid the ongoing pandemic, the child care industry remains weak and vulnerable to shifting economic conditions. Policymakers eying rate hikes should not overlook their potential to further damage the child care sector in the United States.

Making sustained, robust public investments in care would go a long way to protecting the child care sector now and in the future, regardless of the rate of inflation or other macroeconomic conditions. Yet even small fixes can yield large dividends for the fragile child care market. The above policy recommendations are examples of modest tweaks policymakers can undertake today. The purpose of these policies is to support the child care sector so it can weather a potential economic downturn and the higher cost of capital due to rising interest rates.

Yet these proposals alone are insufficient to protect and restore a healthy child care sector in the long term. Until Congress commits to making the necessary investments to expand child care access, raise care workers’ wages, and lower families’ out-of-pocket child care costs, it must ensure that the already-struggling sector is not further harmed by the monetary policy choices of the moment. Inflation may be an important economic concern today, but high-quality and affordable child care has the potential to unleash economic growth that will be with us today, tomorrow, and for generations to come.