New research shows that 1 in 4 adults in the United States suffers from transportation insecurity

Access to transportation is crucial to ensuring that people can meet their basic needs and participate in society and the economy. It goes without saying that if people can’t get where they need to go, they will struggle to work and learn, to buy food, to see friends and family, and to receive medical care.

When a person can’t regularly move from place to place in a safe or timely manner because they lack the resources necessary for transportation, that person is experiencing transportation insecurity. Until recently, the number of people experiencing transportation insecurity in the United States had been a mystery, largely because researchers have lacked the tools to measure transportation insecurity.

Thankfully, this is no longer the case. Yesterday, my colleagues Alexandra Murphy, Jamie Griffin, Karina McDonald-Lopez, Natasha Pilkauskas (all of the University of Michigan), and I published new findings that use a novel measurement tool—the Transportation Security Index—to quantify the prevalence of transportation insecurity in the United States.

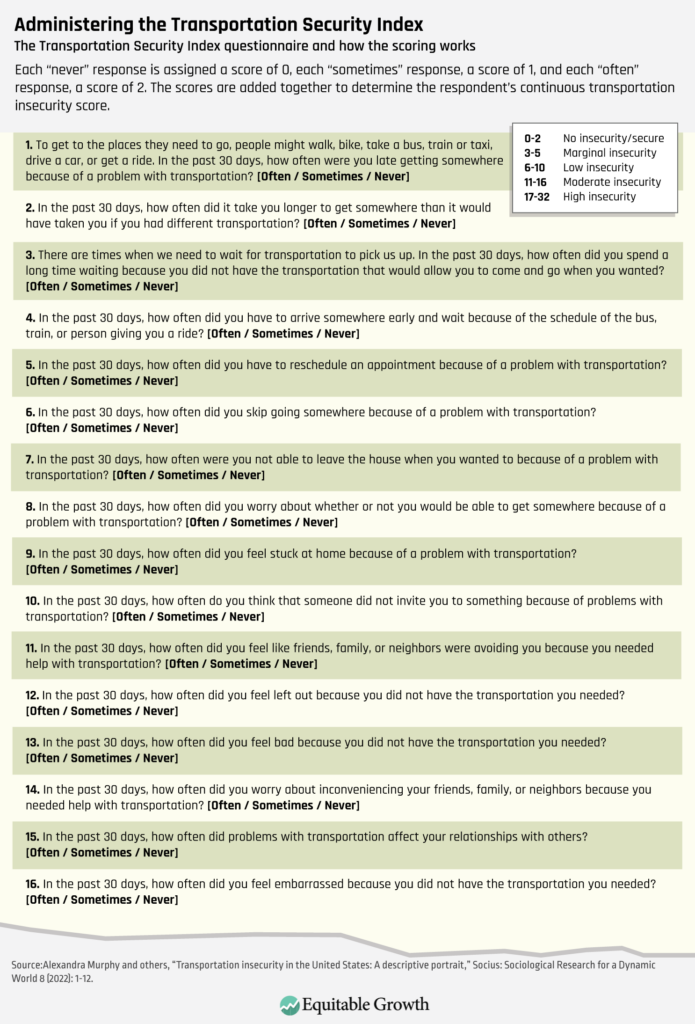

Modeled after the Food Security Index, the Transportation Security Index identifies those experiencing transportation insecurity by looking at their symptoms, such as feeling stuck at home because of a lack of access to transportation or arriving early or late somewhere due to transportation scheduling issues. Researchers can administer a questionnaire, score responses to each question, and add up the scores to come to a quantitative measure of a person’s overall level of transportation insecurity. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

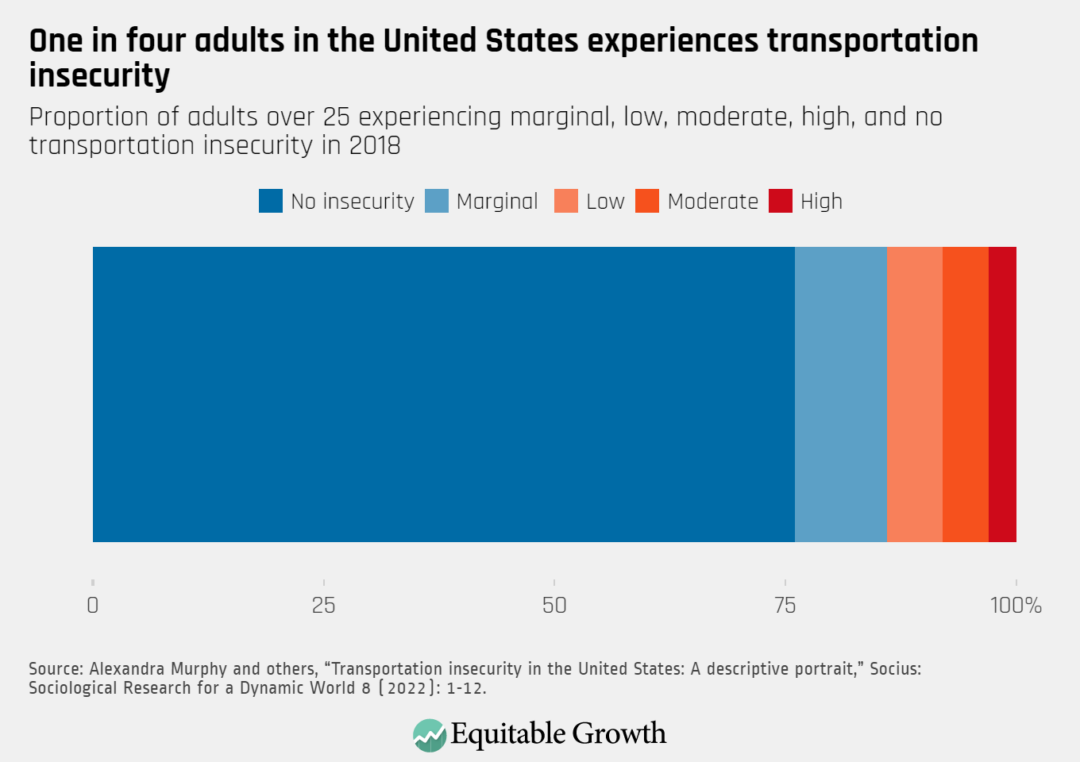

When my co-authors and I administered the Transportation Security Index questionnaire to a nationally representative sample of 1,999 adults aged 25 and older in the United States, the results were striking. In 2018, the year of the data collection, about 1 in 4 adults experienced transportation insecurity, with nearly 1 in 10 experiencing moderate or high levels of insecurity. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

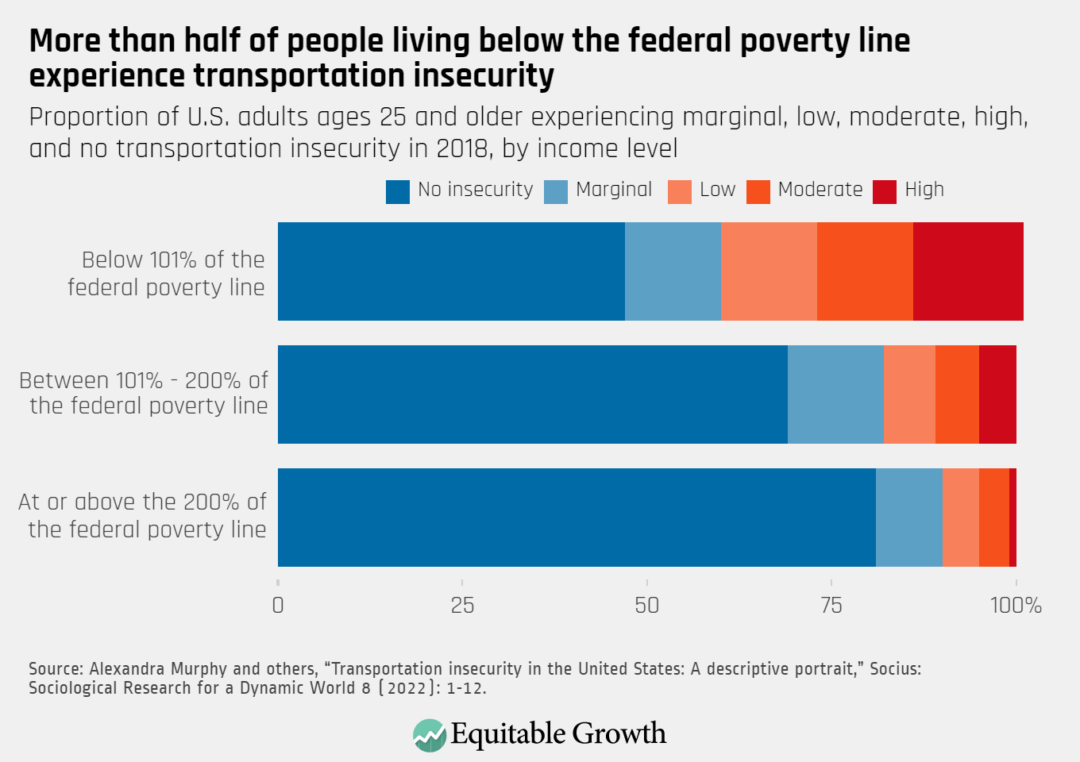

As one might expect, my co-authors and I find that transportation insecurity and poverty are highly correlated. Indeed, we find that more than half of adults who experience poverty are also experiencing transportation insecurity—a relationship that remains strong even when controlling for factors such as car ownership, race, education level, and urbanicity. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

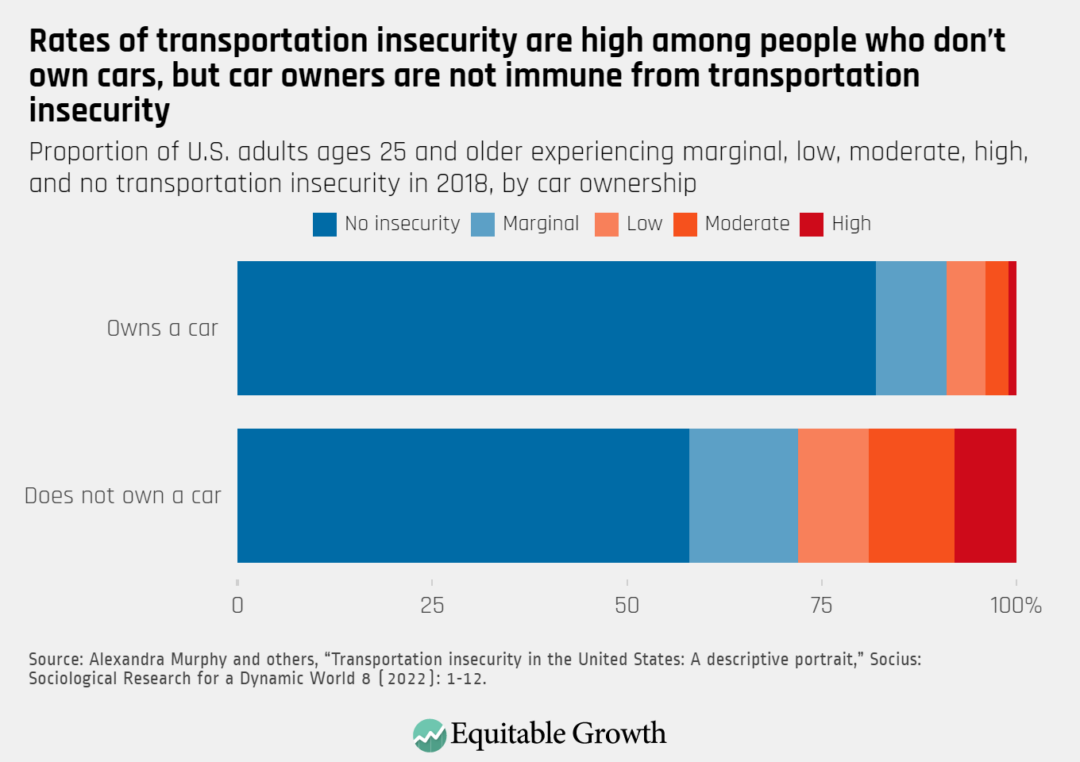

Perhaps less intuitively, though, our results suggest that car ownership and transportation insecurity are not as correlated as one might expect. While car owners are much less likely to experience transportation insecurity than people who do not own cars, car owners are not immune from transportation insecurity—perhaps because cars, while helpful for getting around, are not effective tools if their owners cannot afford gas, insurance, or repairs, or if they must share the car with many other family members. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

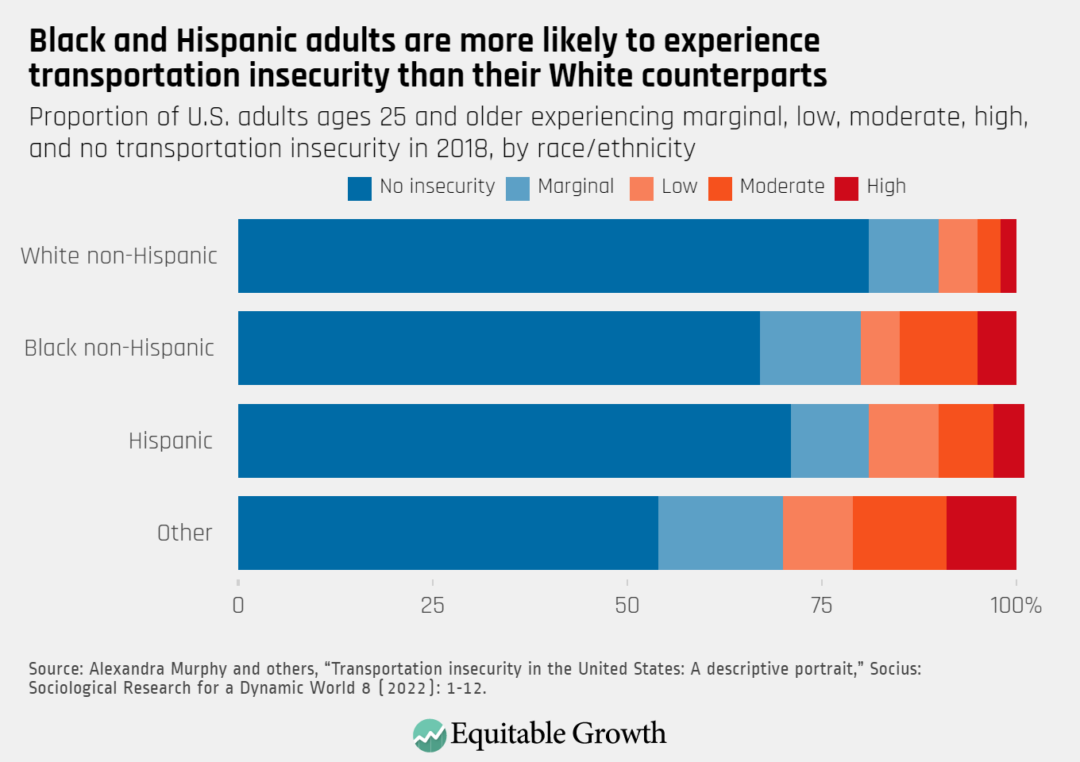

As is the case with other forms of material hardship, my co-authors and I find that transportation insecurity rates in the United States are highest among the racial and ethnic groups that also often experience racism and discrimination: Black and Hispanic adults. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

This creates a vicious cycle, in which experiences of discrimination in institutions, such as the labor market, education system, and financial system, as well as in city planning, lead Black and Hispanic adults in the United States to have fewer resources to access adequate transportation. Transportation insecurity, in turn, prevents them from accessing more and better economic opportunities and even from meeting their basic needs.

In sum, our research demonstrates that transportation insecurity can be measured—and shows how prevalent it is in the United States.

Future research is needed, however, to determine how rates of transportation insecurity in the United States have changed since 2018. For instance, transportation insecurity levels may have fallen as staying home and working from home became more common amid the COVID-19 pandemic—or they may have risen as the price of used cars and gas increased. Likewise, further research is needed to examine the causal links between transportation insecurity and outcomes that are crucial to the functioning of the U.S. economy, including labor force participation, access to healthcare, school attendance, and consumption patterns.

Such research would help guide policymakers as they seek solutions to address widespread transportation insecurity and its impacts on U.S. workers and their families.