This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Equitable Growth’s incoming President and CEO Michelle Holder penned a note this week, sharing her thoughts on joining the organization at this critical moment.

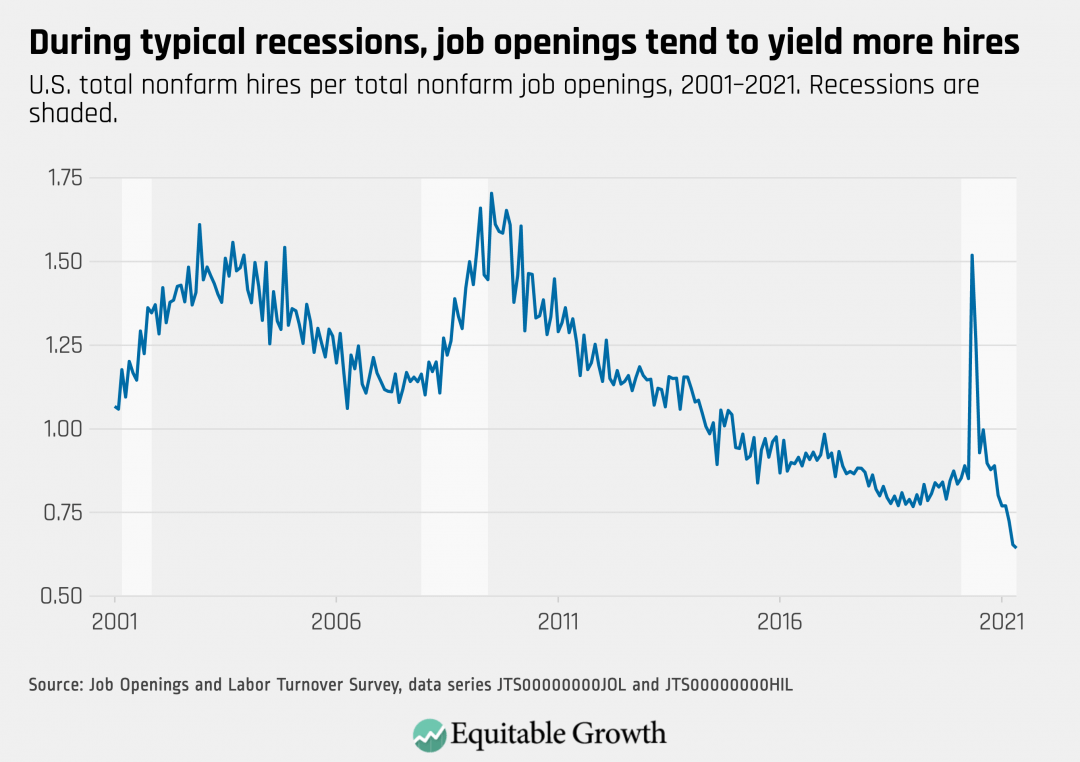

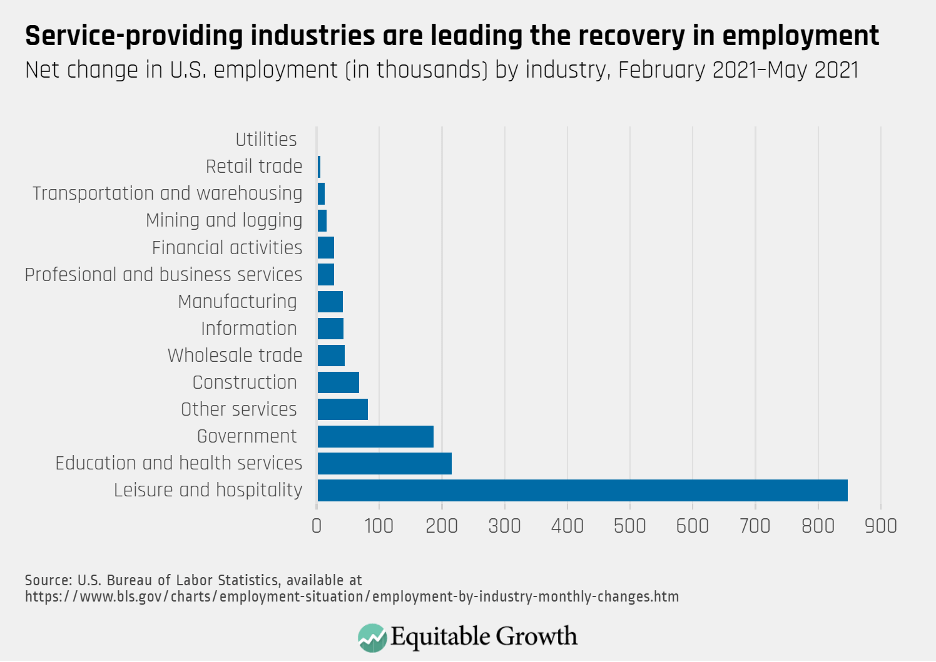

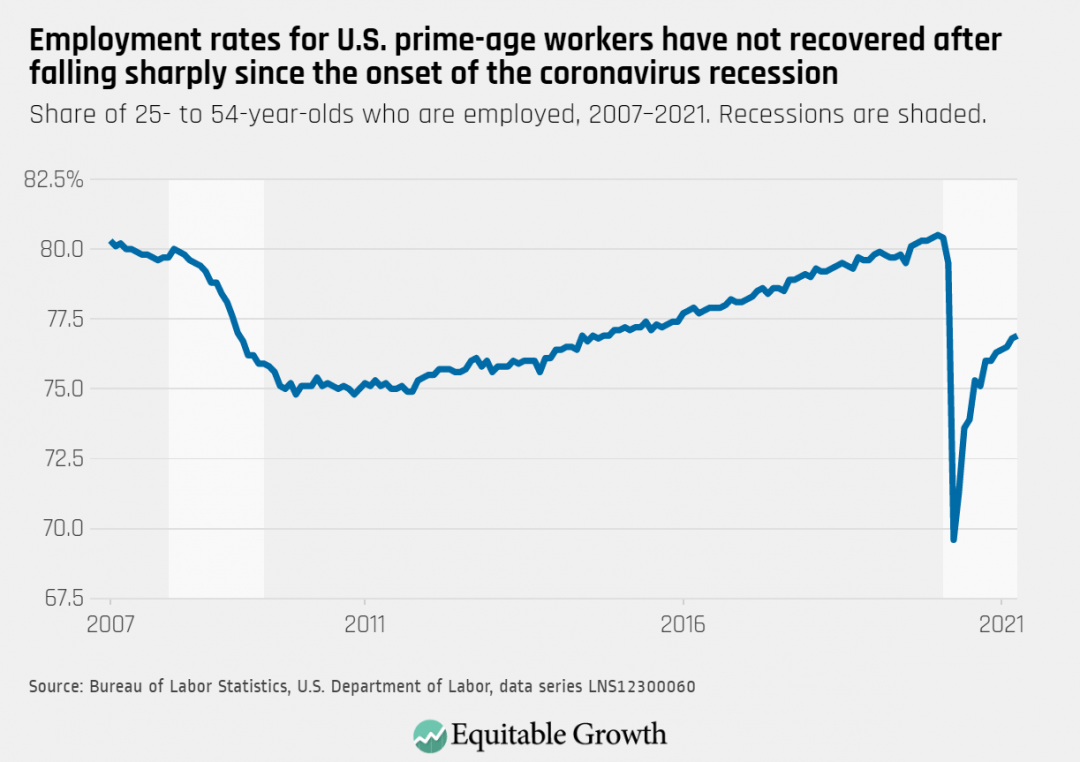

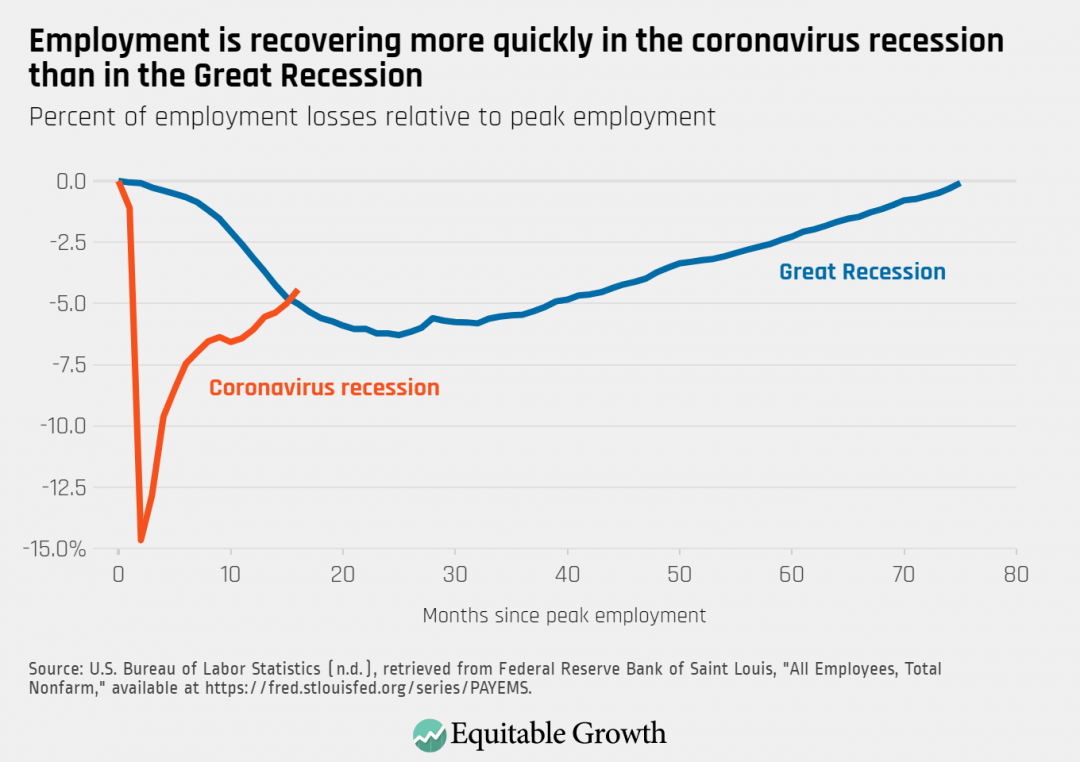

Kate Bahn, Alix Gould-Werth, and Carmen Sanchez Cumming write that the current state of the U.S. economy is strong, but as it moves toward recovery, the policy actions taken over the next several months will be vital to ensure growth is sustainable and broadly shared. They explain why investments in social infrastructure and boosting workers’ bargaining power are essential tools in policymakers’ belts to keep the economic and labor market recovery on its current trajectory. They also delve into why current disruptions in the labor market are the prime reason to boost worker power and productivity, ensure the labor market is competitive, and enhance social supports for workers. Some proposals they urge policymakers to act upon are increasing the minimum wage, making it easier for workers to form and join unions, improving and updating income support programs such as Unemployment Insurance and permanently expanding the Child Tax Credit, and implementing paid family and medical leave for all workers in the United States.

Inflation is certainly a hot topic these days among observers of U.S. economic activity and among consumers. This is important because consumer expectations of future inflation can spur behavior that further increases inflationary pressure. Carola Binder writes about average inflation targeting at the Federal Reserve, recent trends in inflation expectations and uncertainty among consumers and investors, and what actions the Fed can take to stabilize those expectations. Binder details her new methodology to estimate consumer uncertainty about inflation both in the short term and long term, and explains how the methodology can help researchers studying these trends. Her study finds that not only has short-run inflation uncertainty grown amid the coronavirus recession, but long-run inflationary expectations have also risen. While this isn’t necessarily cause for panic yet, Binder explains that it could have important implications if long-run uncertainty remains elevated and restricts consumers’ activities, such as taking out mortgages or loans. She then recommends actions the Fed can take to alleviate some of these concerns.

Two congressional hearings this week focusing on market concentration and competition policy featured testimony from Equitable Growth staff. On Tuesday, Director of Markets and Competition Policy Michael Kades testified before the Senate Subcommittee on Competition Policy, Antitrust, and Consumer Rights on anticompetitive behavior in pharmaceutical markets. His statement centered on specific actions that brand-name drug manufacturers take to limit competition from generics and biosimilars, as well as the failures of U.S. antitrust laws to prevent this behavior and how congressional action could increase competition and benefit consumers. And on Wednesday, Director of Labor Market Policy and interim chief economist Kate Bahn testified before the Joint Economic Committee on how rising concentration increases economic inequality and decreases U.S. economic efficiency. Bahn’s statement detailed the causes and impact of monopsony, how it exacerbates economic disparities, and what Congress can include in a robust, procompetitive policy agenda that would reduce corporate power.

The Western Economic Association International held its annual conference virtually this year at the end of June. Equitable Growth organized and participated in sessions for the first time, and our network of scholars was well-represented in the program. Highlights included grantee Emi Nakamura of the University of California, Berkeley giving the keynote address; Director of Academic Programs Korin Davis participating on a panel on best practices for submitting grant proposals; and Macroeconomic Policy Analyst Michael Garvey organizing and chairing a paper session on climate change and the macroeconomy. We look forward to future opportunities for engagement both with WEAI and other regional and economics and social sciences conferences in the future.

Links from around the web

Financial markets are signaling a potential reversal of the current economic narrative, away from inflation and toward potentially slower growth. The New York Times’ Neil Irwin looks at the bond market trends and details what that might mean for economic growth in the coming months. He writes that the new topline numbers are nothing to worry about, but they signal an economy in flux. In fact, Irwin continues, the trends indicate that the U.S. economy has reached peak growth and will likely be more measured going forward. Irwin also writes about the potential positive sides of the bond market adjustments, including making borrowing money cheaper for Americans and relaxing fears of sustained long-term inflation.

Last week, President Joe Biden signed an executive order aimed at promoting competition across the U.S. economy and limiting corporate dominance in markets. The Wall Street Journal’s Brent Kendall and Ryan Tracy explain what is actually included in the order: “a road map that encourages U.S. agencies to adopt policies that push back against corporate consolidation and business practices that might stifle competition and lead to higher prices and fewer product choices.” They detail the implications and potential consequences of the order, what executive agencies will have newfound power to do, and how the order encourages a procompetitive outlook across the federal government. They also credit Tim Wu as the architect of the order, who is currently President Biden’s special assistant for technology and competition policy and who last year co-authored an Equitable Growth report that proposed many of the mandates that are included in the order, including a White House council for competition policy and a whole government approach.

This week, the expanded Child Tax Credit payments started being distributed to families across the United States as part of the American Rescue Plan enacted earlier this year. The expansion makes the tax credit available to the lowest-income families, increases the amount families can receive, and changes the structure of payments from a once-a-year lump sum to monthly deposits. The 19th’s Chabeli Carrazana interviewed several families to see how this funding, which will go out to 88 percent of U.S. families, will affect their lives and well-being. For some families, it will enable access to high-quality child care or extracurricular activities for their kids, or allow them to pay off outstanding loans or bills that accumulated over the pandemic months. For others, it could be what they need to get out of poverty—it’s estimated, Carrazana explains, that the expansion could cut the child poverty rate in the United States almost in half. The impact that these payments will have are life-changing for both mothers and their children, and the stories Carrazana relays are incredibly moving examples of why this program should be expanded permanently rather than allowed to expire next year.

Will the pandemic be the beginning of the end of the 5-day work week in the United States? Vox’s Anna North seeks to answer this question. North first explores how entrenched the 5-day work week is in the U.S. economy and society, and how it first came about as a victory for labor organizers in the early 20th century. She then describes how the pandemic has thrown a wrench in these standards, as salaried workers have increased their hours dramatically with the transition to working from home and hourly workers have noticed an increase in unstable and last-minute scheduling practices by their employers. As workers have quit their jobs and begun demanding better working conditions in recent months, some companies (and even countries, such as Iceland) are testing 4-day work weeks. These experiments have already produced positive results for both companies and workers, with a study showing the same or even increased worker productivity alongside improved well-being and work-life balance. North concludes with the changes that would be necessary in the U.S. labor market and economy to be able to achieve a 4-day work week.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Policymakers should ensure that the U.S. labor market recovery lasts by boosting workers’ bargaining power and strengthening social infrastructure,” by Kate Bahn, Alix Gould-Werth, and Carmen Sanchez Cumming.