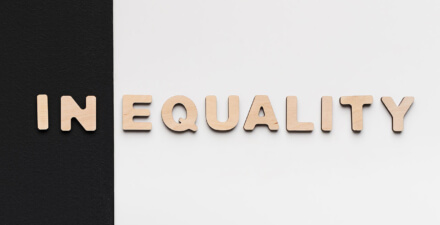

Race and the use of force by police matters to build a more equitable U.S. society and economy

There are widespread concerns in the United States about the treatment of Black Americans by state and local police forces across the country. These concerns are rooted in the long history of police mistreatment of Black Americans and are reflected in the fact that only 33 percent of Black civilians believe that police officers use the right amount of force for the situation and only 35 percent believe police treat racial and ethnic groups equally.

These concerns are voiced most forcefully in the ongoing protests over police shootings of unarmed Black civilians and by the Black Lives Matter movement. In the aftermath of the May 2020 murder of George Floyd by a police officer in Minneapolis, this movement has grown exponentially, with more than 1,700 demonstrations across all 50 states in the immediate wake of his murder. This protest movement—alongside the ongoing economic and social harms that disproportionately continue to fall on Black workers and their families amid the coronavirus recession—lay bare the longstanding questions about the degree of systemic racism in the United States today.

Yet many police and political leaders continue to argue that these high-profile police-use-of-force incidents targeting Black Americans are largely one-off events. These leaders argue that these incidents are perpetrated by so-called “bad-apple” police officers rather than are a symptom of a broader problem with race and the police use of force

To be sure, it is hard to know even in any number of specific incidents whether it is race itself that matters or if there are certain police officers who may use too much force regardless of race. The purpose of my research co-authored with Mark Hoekstra at Texas A&M University and presented in this column is to demonstrate a way to distinguish between these competing hypotheses.

Why is there no clear evidence on whether race matters systematically for police use of force?

Documenting whether race matters in the use of force by police is difficult. One reason is because researchers typically only observe interactions between police officers and civilians that end in force. This means researchers need to make some pretty strong “benchmarking” assumptions about the unobserved interactions that do not end in force. That is, they need to assume how many total interactions police have with Black and White civilians to determine whether race matters.

Further, the underlying danger of the interactions themselves can be very different depending on the race of the officers and civilians involved. This is partly because police officers typically initiate interactions and partly because White and Black civilians do not always act the same. This makes it hard to distinguish the effect of race from other things. If one wants to know the impact of the race of the civilian in incidents, for example, one needs to quantify exactly what was different about the situations. In practice, that is impossible, at least in most contexts.

Here’s just one case in point. A recent study estimates that Black men are 2.5 times as likely as White men to be killed by police during their lifetimes. But this finding begs two questions. Do Black men have more or less than 2.5 times as many interactions with police as White men? And more importantly, are those interactions more or less dangerous than the police interactions with White men?

Currently, these questions are unanswered, which forces researchers to make assumptions—perhaps better described as educated guesses. In our research, we move beyond educated guesses by designing a natural experiment.

Designing a natural experiment to assess race and the police use of force

In our paper, titled “Does Race Matter for Police Use of Force? Evidence from 911 Calls,” we wanted to look at a context that came as close as possible to the ideal experiment where Black and White police officers are randomly assigned to interactions with civilians of different races. We do this by looking at emergency 911 calls in two cities where municipal authorities agreed to share their data anonymously. Neither the dispatchers nor police officers in these two cities have any discretion as to which officer is first dispatched to a call. In this context, it is essentially conditionally random whether a Black or White cop is dispatched to the scene.

In addition, we observe all police interactions even if they don’t end in an arrest or use of force. We do so because in this way, we don’t need to make any potentially problematic assumptions about interactions that we do not observe in the data.

We then assess whether race matters in the interactions of the police officer and civilians. We ask: How much more force do White officers use in Black neighborhoods, compared to White neighborhoods? Do Black officers scale up their use of force just as much as their White peers? If so, this would suggest that perhaps race doesn’t matter much. But if Black officers scale up use of force less, then it would suggest there is, in fact, a race problem.

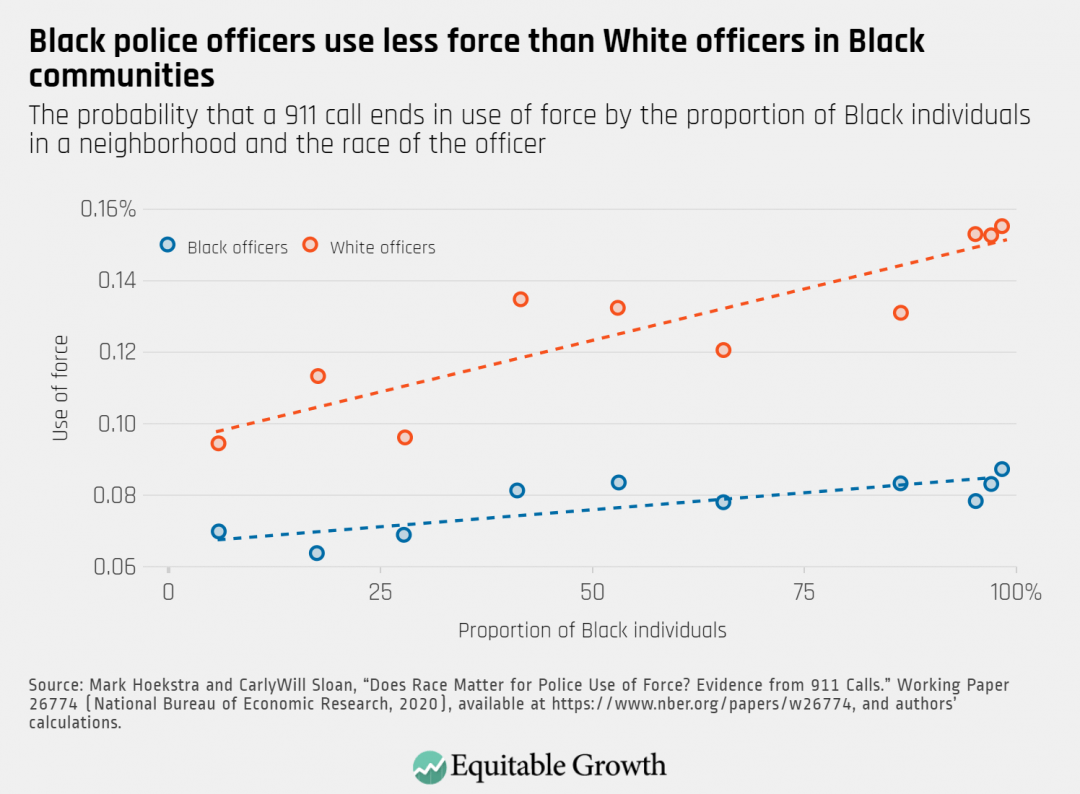

Our primary finding is telling. We find that Black police officers modestly increase their use of force when sent to neighborhoods with a higher proportion of Black civilians, but White officers use significantly more force as they are dispatched to more Black neighborhoods. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

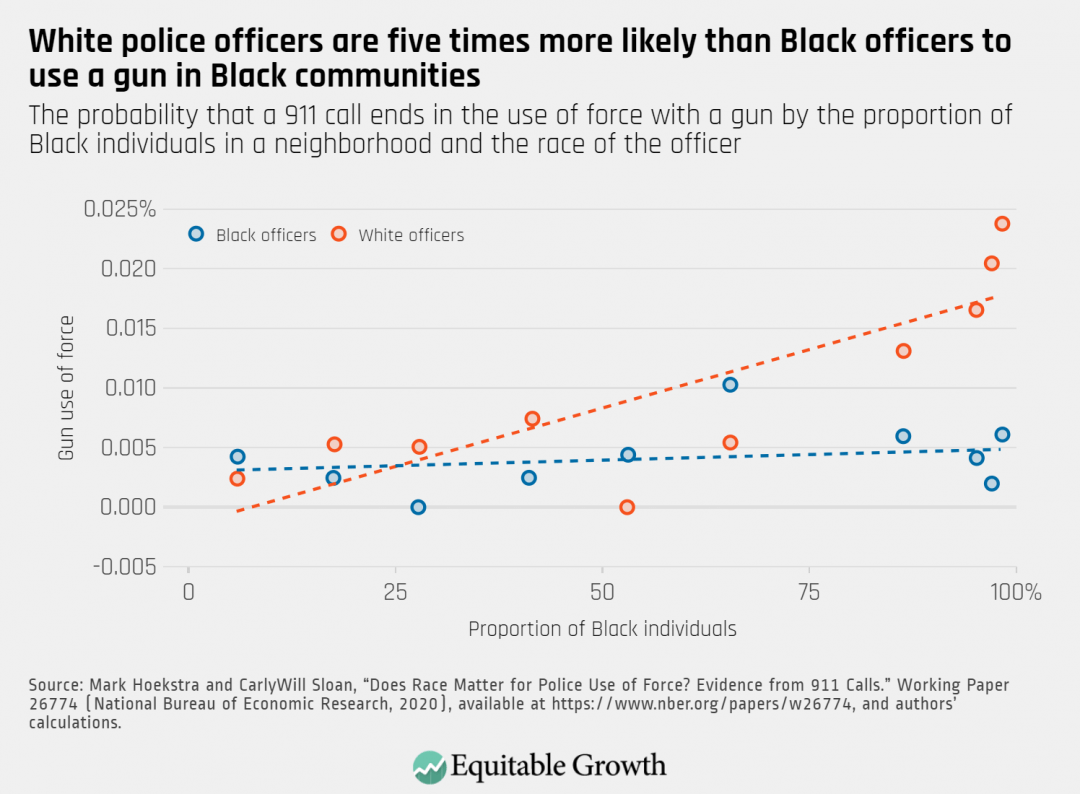

We document even more striking results for use of force with a gun. While White and Black officers fire their guns at similar rates in White neighborhoods, White officers are five times more likely than Black officers to fire their guns in predominantly Black neighborhoods. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Our findings also make clear that in one major city with a predominantly White and Black police force, the city seems to attract a different type of White candidate to its police force than Black candidates. Across all neighborhoods, White officers use force 60 percent more than Black officers and fire their weapons twice as often. This is true even though both White and Black police officers are responding to otherwise-similar calls due to the dispatch protocol.

Conclusion

The central finding of our paper raises this important question: If calls in predominantly Black neighborhoods were that much more dangerous to respond to than calls in predominantly White neighborhoods, then why don’t Black police officers increase their use of force as much as White officers do? I and my co-author believe the only reasonable interpretation is that race matters in a systematic way with respect to the use of force by police.

Beyond showing that race is an important determinant of police use of force, a major contribution of our work is showing there is a clear and transparent way to test whether race matters, without making a lot of assumptions that are difficult to validate. In many ways, the hardest part about what we did in our research was finding cities with the right kind of 911 protocols that were also willing to share data.

There is no reason why cities can’t adopt similar protocols and either share these data or perform the analysis internally with the help of researchers. Doing so would enable a simple yet compelling analysis of whether race systematically matters for use of force in that city. If any city wants to do this, we would be happy to help.

—CarlyWill Sloan is an assistant professor of economic sciences at the School of Social Science, Policy & Evaluation at Claremont Graduate University. Her co-author on the working paper, Mark Hoekstra, is a professor of economics at Texas A&M University.