Overview

In recent decades, wage stagnation and increasing income inequality have plagued the U.S. labor market. U.S. workers experience persistent racial and gender disparities in economic outcomes. These trends largely continued even during the tight labor market immediately prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

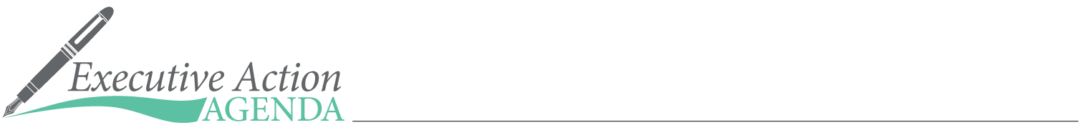

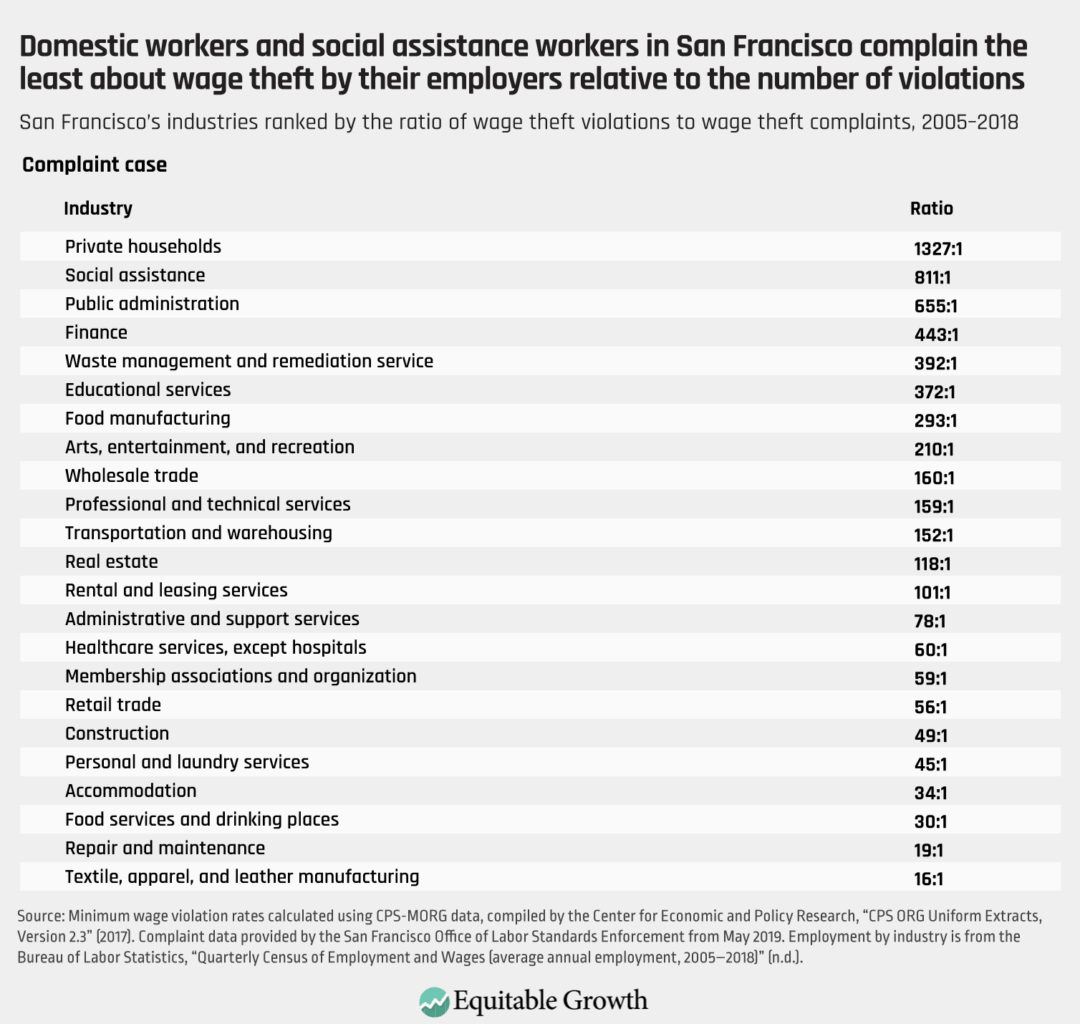

Declining worker power and the diminished capacity of the federal government and its state and local counterparts to enforce existing labor market protections contribute to these long-term trends. Wage theft, or when employers pay their workers less than what’s required by law, is just one phenomenon that feeds into these outcomes. The odds that a low-wage worker will be illegally paid less than the minimum wage ranges from 10 percent to 22 percent, with each violation costing that worker an average of 20 percent of the pay they deserve. Women, people of color, and noncitizens are especially vulnerable to wage theft.

Research finds that employers have little incentive to comply with the Fair Labor Standards Act, which established the federal minimum wage, and the National Labor Relations Act, which protects the right to unionize, under current enforcement regimes.

Fortunately, U.S. workers are increasingly displaying an increasing interest in unionization, despite rising attempts by employers to bust unions and delegitimize their status. From high-profile organizing efforts at Starbucks Corp. and Amazon.com Inc. to smaller businesses and various professions, union activity is on the rise in the United States. With 71 percent of U.S. public support, unions are at their highest approval rating since 1965.

Unions are essential to boosting U.S. worker power and decreasing wage stagnation and income inequality. Studies show that through collective bargaining, unions provide benefits such as increasing the likelihood of access to employer-sponsored health insurance and paid leave, as well as helping determine how new technologies are implemented in the workplace. Union workers also tend to have higher wages than otherwise-similar nonunion workers, thanks to the “union wage premium.”

Additionally, unions provide spillover benefits to workers, such as better education on rights in the workplace and a decreased risk of employer retaliation for organizing or joining a union. Union members also more successfully apply for Unemployment Insurance after involuntarily losing a job, experience better protection against wage theft and decreased levels of sexual harassment, and report improved health and safety and reduced violations of other U.S. labor regulations. All union members benefit from these gains, but they are especially large for Black and Latino unionized workers. This is, in part, due to a reduction in workplace discrimination that otherwise unfairly maintains wage disparities between Black and Latino workers and their White peers.

While unions can do a lot to improve U.S. workplaces, the Biden administration can also provide more institutional support to increase U.S. worker power. President Joe Biden has already taken some steps in the right direction—for example, by signing an executive order establishing a taskforce on worker organizing and empowerment and launching a resource center through the U.S. Department of Labor for workers who want to organize. Yet more can still be done. Below are some executive actions the Biden administration can take, all of which stand to boost wages, increase worker power, and help decrease income inequality.

Improve the strategic enforcement of labor standards at all levels of government and institutionalize enforcement within the U.S. Department of Labor

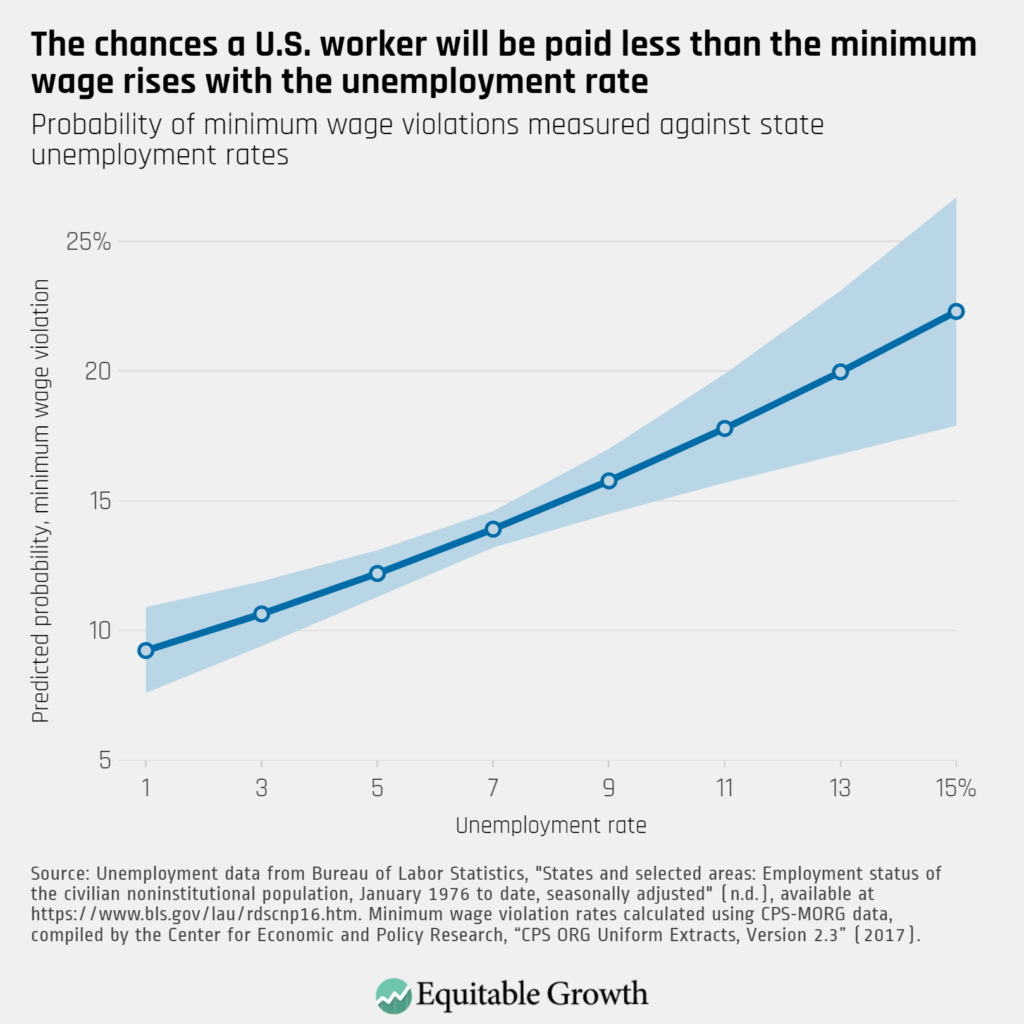

Instead of relying on complaint-based enforcement of labor standards, agencies such as the U.S. Department of Labor should institute strategic enforcement to increase the real and perceived costs of violations. As outlined by David Weil of Brandeis University, strategic enforcement includes a range of actions: targeting industries high in violations but low in complaints, proactively investigating targeted industries, maximizing penalties for violators, launching information campaigns, and instituting robust compliance agreements. Janice Fine, Jenn Round, and Hana Shepherd, all of Rutgers University, and Northwestern University’s Daniel Galvin also outline how a triage system can supplement strategic enforcement by maximizing statutory tools to disincentivize the obfuscation of noncompliance and by assessing large penalties to deter future violations.

Strategic enforcement also can be applied at the state and local levels. State and local labor enforcement agencies operate in vastly different political climates than federal enforcement agencies, and each have their own variety of powers and limitations. Prioritizing state and local strategic enforcement would not only give states the opportunity to go above and beyond what the U.S. Department of Labor can do and experiment with different tactics and methods, but also allow for the avoidance of one-size-fits-all solutions. The U.S. Department of Labor can provide guidance to state and local labor departments on how to best use strategic enforcement, allowing for maximum impact despite federal budgetary and bureaucratic limitations.

A key component to this strategy is co-enforcement, or sustained partnerships with worker centers, unions, legal advocacy organizations, and other community-based groups that are embedded in low-wage worker communities and high-violation sectors of the U.S. economy. These organizations provide an important connection to workers for labor law enforcers and often have access to information on compliance with labor standards that would be difficult for state and local or federal officials to gather on their own. They also can continue to monitor employers over time after inspectors have moved on to new cases. State and local labor enforcers are likely to have better connections to these groups than federal enforcers, making them a key facet in ensuring successful strategic enforcement.

Finally, the U.S. Department of Labor should institutionalize its enforcement directives within its Wage and Hour Division to ensure more consistent and even application from one presidential administration to the next. This would prevent large swings in policy every 4 or 8 years, provide more stability to employees and employers, and allow for better and more concrete planning among stakeholders. While this action could also limit positive developments, instituting a more concrete floor of enforcement would provide a demonstrable benefit to U.S. workers.

Require a labor cost analysis from contractors who submit bids for federal contracts

When it comes to competing for federal contracts, contractors often find themselves in a race to the bottom to provide the least expensive services to the federal government. While this ostensibly saves the government money, those cheap prices come at a cost. The biggest driver of a contractor’s costs is labor. So, when contractors skimp on the price, it’s their workers who often bear the burden.

During the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and the 8 years following it, more than 300,000 workers on federal contracts were victims of wage-related labor violations. Research shows that many contractors who are penalized for wage and/or health and safety violations also have contract performance issues such as cost overruns, falsifying legal compliance, and fraudulent billing practices. Due to occupational segregation and systemic bias, the lowest bids disproportionately harm workers of color and women workers, both of whom are disproportionately employed in low-pay and high-risk industries.

The Biden administration should implement an executive order requiring contractors to include a labor cost analysis when bidding on a federal contract. This would require contractors to submit staffing plans in their solicitations, thereby committing contractors to paying proposed wage rates. Such an executive order also would allow the government to audit and evaluate wage information in proposals for successor contracts.

This would essentially force contractors to either self-report their wage violations or comply with good-faith actors who also are competing for the same contract. As such, a labor cost analysis can serve as a powerful tool to help boost wages among those who are most at risk of having their wages stolen.

Allow unions better access to worksites

When it comes to helping organize workers, one big issue that unions and their representatives face is reaching workers at their worksites. One part of the broader suite of legal and illegal tactics that U.S. employers use to discourage unionization is preventing unions from accessing their worksite at all, even if union members only talk to employees during nonworking hours and in nonworking areas such as breakrooms and cafeterias.

President Biden should issue a presidential memorandum directing federal agencies to develop plans that would allow representatives of unions and appropriate nonprofit organizations to gain access to nonworking areas of worksites for the purpose of communicating with workers employed by federal contractors during nonworking time. This action would help union representatives counter the systemic advantage that employers have when it comes to implementing union-busting tactics. Something as simple as allowing union access to worksites could help boost union organizing and membership and make workers aware of their rights in the workplace, which would in turn provide other benefits that come from unionization to both unionized and nonunionized employees.