Two things state and local governments can do to mitigate the coronavirus recession in the United States

The U.S. economy is infected by the coronavirus pandemic, and a deep recession is practically inevitable. Congress and the Federal Reserve will lead the effort to fix the economy with fiscal and monetary stimulus, but state and local governments, too, have an important role to play.

Even the massive $2.2 trillion stimulus package passed by Congress last week is unlikely to offset the imminent collapse in spending across the country by consumers and businesses alike. Although states and localities cannot run deficits due to balanced budget requirements, they still control many policy levers that influence spending. To supplement whatever boost the national government can provide, states and localities can stimulate their own economies significantly by adjusting laws and regulations to promote spending, which, in turn, will help the U.S. economy overall recover more quickly.

Here are two detailed examples of how state and local governments can stimulate spending by promptly changing how utilities are regulated and how building construction is restricted, followed by three more short examples. (For more suggestions, see my book on legal remedies to recessions and my essay in the book the Washington Center for Equitable Growth published earlier this year, Vision 2020: Evidence for a stronger economy, for a range of federal, state, and municipal policy ideas.)

Implement countercyclical utility regulation

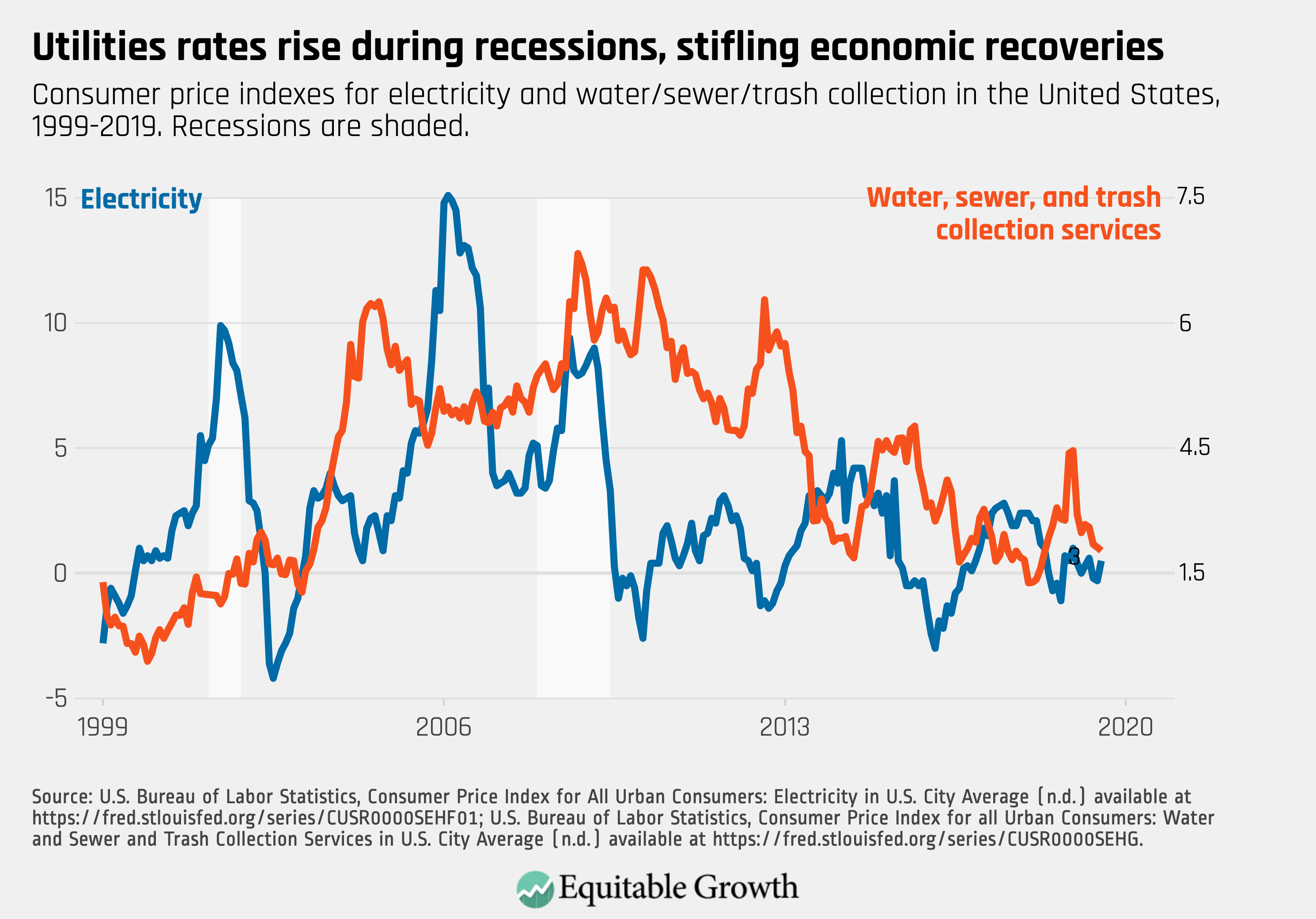

States can lower the financial burden that utilities—gas, electricity, and water companies—impose on consumers during the recession. States guarantee utility companies a nearly fixed profit, no matter how gloomy the economic situation. This legislative guarantee insulates utility profits from economic downturns, worsening recessions. That effect occurs because, at present, utility regulation aims to give utilities a median rate of return of approximately 10 percent a year every year. In good economic times, demand for utilities is high. This means that the utility can earn 10 percent without charging a particularly high price. In recessions, however, demand for utilities falls. For a utility to earn 10 percent in a recession, it needs to raise prices.

A utility regulator aiming to keep annual utility returns constant, as most regulators do, will consent to a rate increase. This pattern of regulation explains why utility prices have increased markedly during the previous two recessions. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

This regulatory practice reflects disastrous economic policy. Utility investors, who are insulated from recessions by regulation, are relatively affluent and have access to capital markets. They can easily borrow or sell assets in order to keep up spending in response to a downturn in income. Many or even most utility customers, by contrast, live paycheck to paycheck. Utility costs swallow 10 percent or more of many U.S. workers’ income, and when those costs rise during recessions, low- and medium-wage workers cut spending on everything else, exacerbating the recession.

In recessions—in other words, right now—regulators should lower the guaranteed profit that utilities make. Doing so would increase consumer discretionary income, just like a tax cut. In good times, regulators should permit utility prices to increase, so that utilities earn a fair, risk-adjusted return over the course of the business cycle. This approach, which is already implemented by Chinese utility regulators, would leave consumers with more money during lean times and would increase rates modestly when consumers can actually bear the increase.

Extra consumer spending is unnecessary when the economy is healthy. But that spending is critical when times are lean. Letting utilities profit more during boom times and profit less during lean times—just like nearly any other business—could mitigate the coronavirus recession without harming utility investment. Reducing utility rates by 10 percent over the next 2 years would leave more than $400 in the pockets of consumers. A target profit-rate that exceeds 10 percent could be guaranteed for 3 years or 4 years out, which would guarantee utilities a fair rate of profit over the course of the business cycle rather than year by year—and would pump some adrenaline into the national economy.

Support construction by easing zoning rules

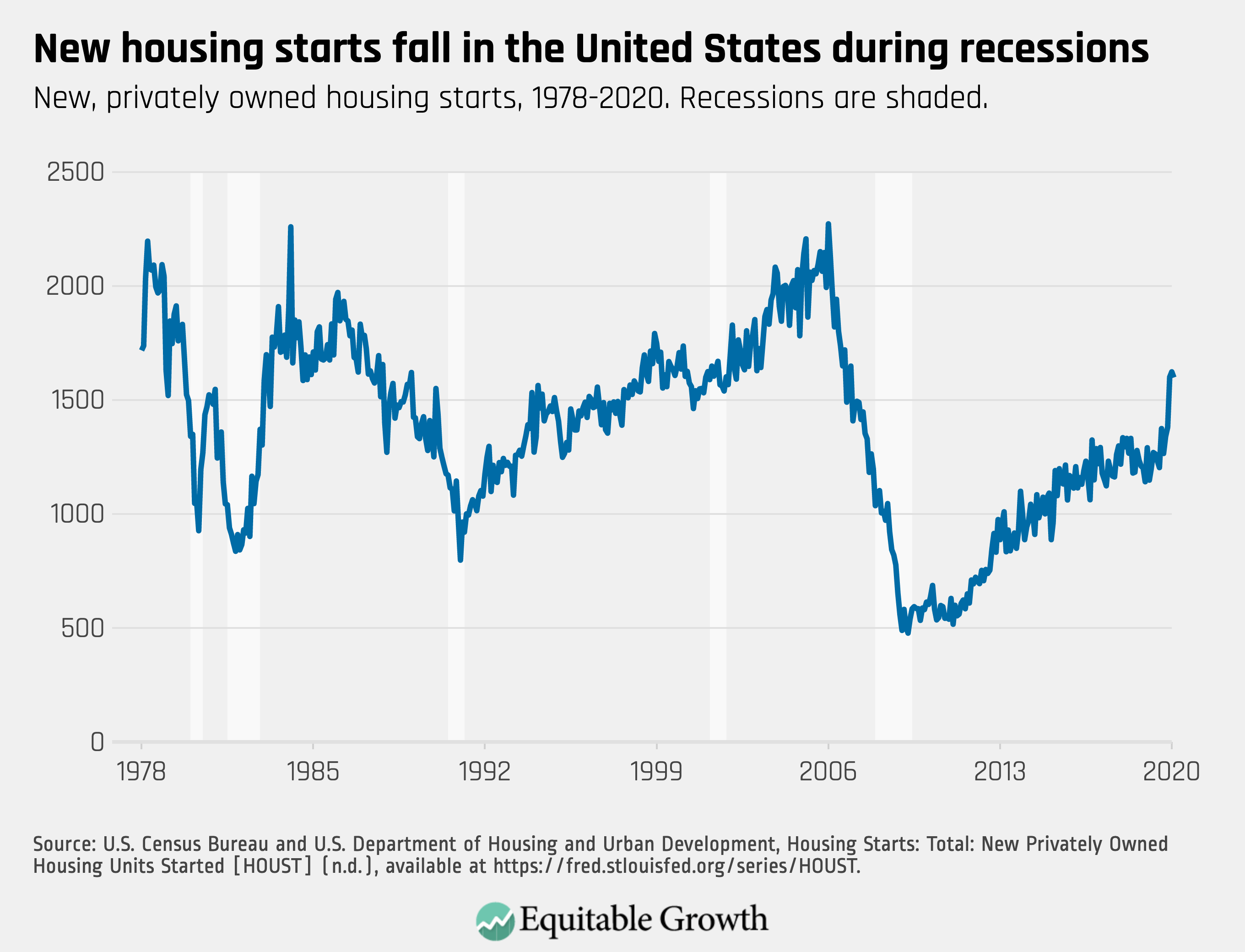

States and local governments—not the national government—dominate zoning rules, and sensible, temporary changes to those regulations could improve state and local economies and, in turn, the overall U.S. economy. Housing construction is a macroeconomically important industry. In many states, however, construction is limited by tight zoning regulations. By loosening these restrictions for a short period, such as for 2 years, states and municipalities could induce skittish investors to pull cash from underneath their mattresses in order to invest in housing “starts.” Doing so would cushion the painful downturn in housing output that will likely occur in response to coronavirus.

Housing is an expensive, long-lived asset. When economic times grow uncertain, housing developers and financiers know that a house will be expensive to build but are unsure that housing demand is sufficient to repay the investment and make a profit. When the Federal Reserve lowers interest rates, it tries to stimulate construction because lowering interest rates lowers a project’s total construction costs, which increases the expected profit from building a new home—and that spurs investors to open their checkbooks—in theory. In reality, however, past experience suggests that when interest rates are already low, additional dips in the rate don’t provide much of a stimulus to investment. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

So, housing developers and financiers need a reason to invest. A temporary loosening of zoning regulations would do the trick. Suppose that California—notorious for its restrictive zoning rules—passed a law enabling any housing project that puts shovels in the ground within 1 year to build larger houses or more units per lot. Developers would suddenly have a unique, fleeting opportunity. If they build immediately, then they could earn profits that would be unattainable if they wait. This type of incentive, passed at the state or even local level, could be enough to stimulate construction spending, mitigating what might otherwise be a terrible downturn in the sector.

Housing starts produce jobs, spark the purchase of building materials, and by increasing supply ease financial pressures on residents by lowering housing costs. Passing these temporary laws at the state level would prevent local homeowners in municipalities from blocking changes. The “burden” of liberalizing zoning rules could be proportionate. A state law, for instance, could provide that any local zoning limits that specify the number of square feet of a project must increase by 25 percent. Multifamily developments could have 25 percent more units. That approach would loosen all local zoning laws to the same degree.

Three other steps that states and localities can take

Although many states and cities cannot use deficit spending to stimulate their economies, they can adopt creative “law and macroeconomic” policies to mitigate what is sure to be a painful economic downturn. State and local governments that enact these measures will suffer less than those that passively wait for the economy to heal itself or for Congress and the Fed to ride to the rescue with additional funding. Countercyclical utilities and zoning regulations are just two examples of the many regulatory stimulus options that are available to state and city governments alone or in league with the federal government, among them home foreclosure and tenant-eviction restrictions and rent adjustments, energy efficiency mandates, and easing unemployment insurance eligibility requirements.

—Yair Listokin is the Shibley Professor of Law at Yale Law School and the author of Law and Macroeconomics: Legal Remedies to Recessions (Harvard University Press 2019).