This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Big Agriculture has a big concentration problem, write Hiba Hafiz and Nathan Miller in this month’s installment of Competitive Edge. U.S. agricultural markets are one of the most highly concentrated industries in the country, with a small group of large corporations wielding incredible buy-side power, or monopsony power, leaving workers along the supply chain with low pay, tough working conditions, and limited ability to fight back. Hafiz and Miller run through the depths of the concentration in the Big Ag poultry, pork, and meat industries, and the anticompetitive and anti-labor effects that arise for workers from small farmers and hatchers to meat processing plant employees. The co-authors explain why policies and actions are needed to combat this monopsony power and suggest that President Joe Biden and his U.S. Department of Agriculture secretary nominee, former Iowa Gov. Tom Vilsack, do more to protect small farms and ensure good jobs.

On February 23, Equitable Growth is hosting a virtual event, “A future for all workers: Technology and worker power,” which will discuss the impact of technology in the workplace and its role in the future of work. The event will feature a keynote address by Mary Kay Henry, the international president of the Service Employees International Union, and two panels covering how workers can and do successfully use technology to amplify their power and voice, and how workers can bargain over how technological advancements may change their jobs. Kate Bahn previews the event in a recent post, which dives into the topic at hand, the speakers and panelists, and the urgency and relevance of discussing technology’s impact on workers. (Visit the event page to learn more and register to join us.)

Equitable Growth released a factsheet this week—the first in a series on executive actions that the new Biden administration could take—detailing how federal agencies should consider using their regulatory power to provide a countercyclical boost to the U.S. macroeconomy and fight the coronavirus recession. The factsheet notes how regulation could increase demand and lower unemployment by encouraging banks to make loans, companies to make investments, and people to spend money, and explains how pro-cyclical policy can delay much-needed boosts in local economies by discouraging spending among low- and middle-income families, which typically have a high propensity to consume. Equitable Growth also urges the Biden administration to create an office within the White House National Economic Council to coordinate effective countercyclical policy across the federal government, an action that can take effect via an update to the executive order that established the NEC.

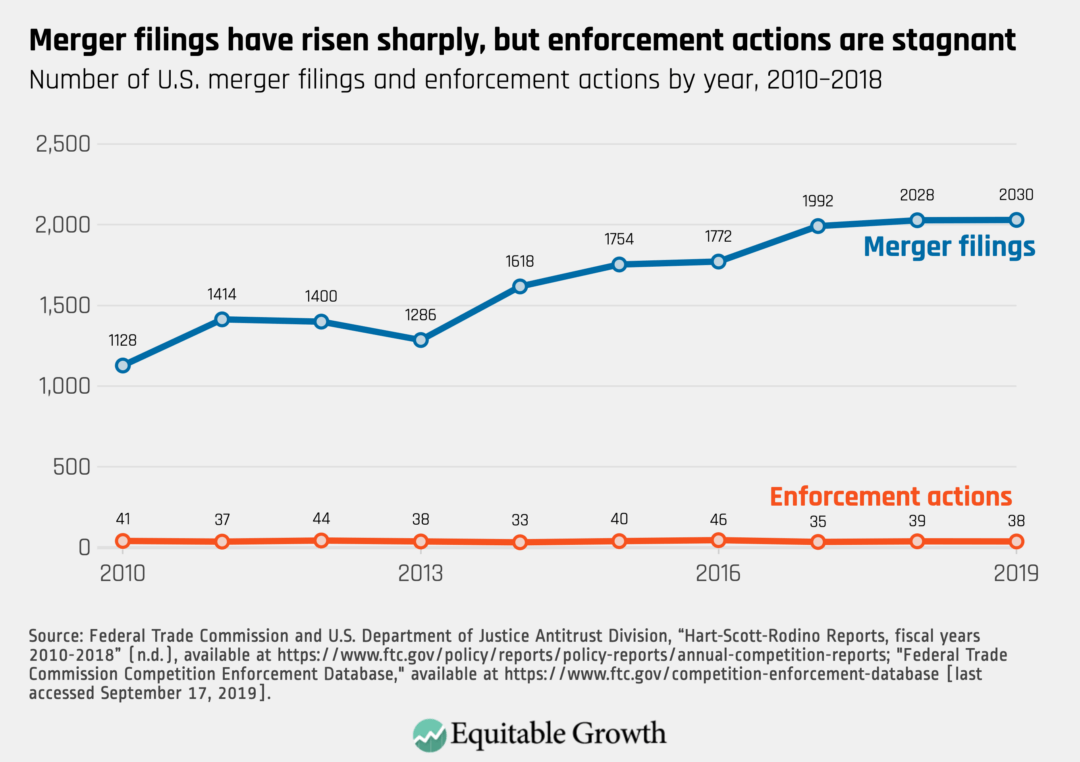

Our second factsheet on executive actions examines how a new Office of Competition Policy could coordinate antitrust and competition policies across the federal government to combat market power. Growing market power disrupts the operation of free and fair markets, and harms consumers, businesses, and workers. It exacerbates inequality and compounds the harms of structural racism. For these reasons, the second factsheet in our series of executive action calls upon the new administration to establish a White House Office of Competition Policy within the Executive Office of the President, led by the National Economic Council and including membership from at least the Council of Economic Advisers, the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, the Office of Management and Budget, and the Domestic Policy Council.

Brad DeLong’s latest Worthy Reads highlights must-read content from Equitable Growth and elsewhere on the internet. This week, he revisits the important recession-fighting proposals Equitable Growth made in its Recession Ready book of essays in partnership with the Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project, an assessment of the nation’s broken Unemployment Insurance system, and more.

Links from around the web

As people and firms rely more and more on certain internet-based services as a result of the pandemic and limited in-person activities, Big Tech giants have gained more and more market power and earned more and more profit. In fact, writes The Wall Street Journal’s staff, as small businesses and brick-and-mortar stores struggle amid the coronavirus recession, and many fail to stay afloat, internet companies—already some of the largest corporations in history—are experiencing unprecedented growth. These gains are expected to outlast the pandemic and the recession, even if regulators act to try to limit this market concentration. The Journal staff look at how the big five tech companies—Apple Inc., Alphabet Inc. (Google’s parent company), Amazon.com Inc., Facebook Inc., and Microsoft Corp.—have fared over the past year and how each has tapped into emerging markets as a result of new demands from consumers amid the pandemic, expanding their market dominance to potentially irreversible levels.

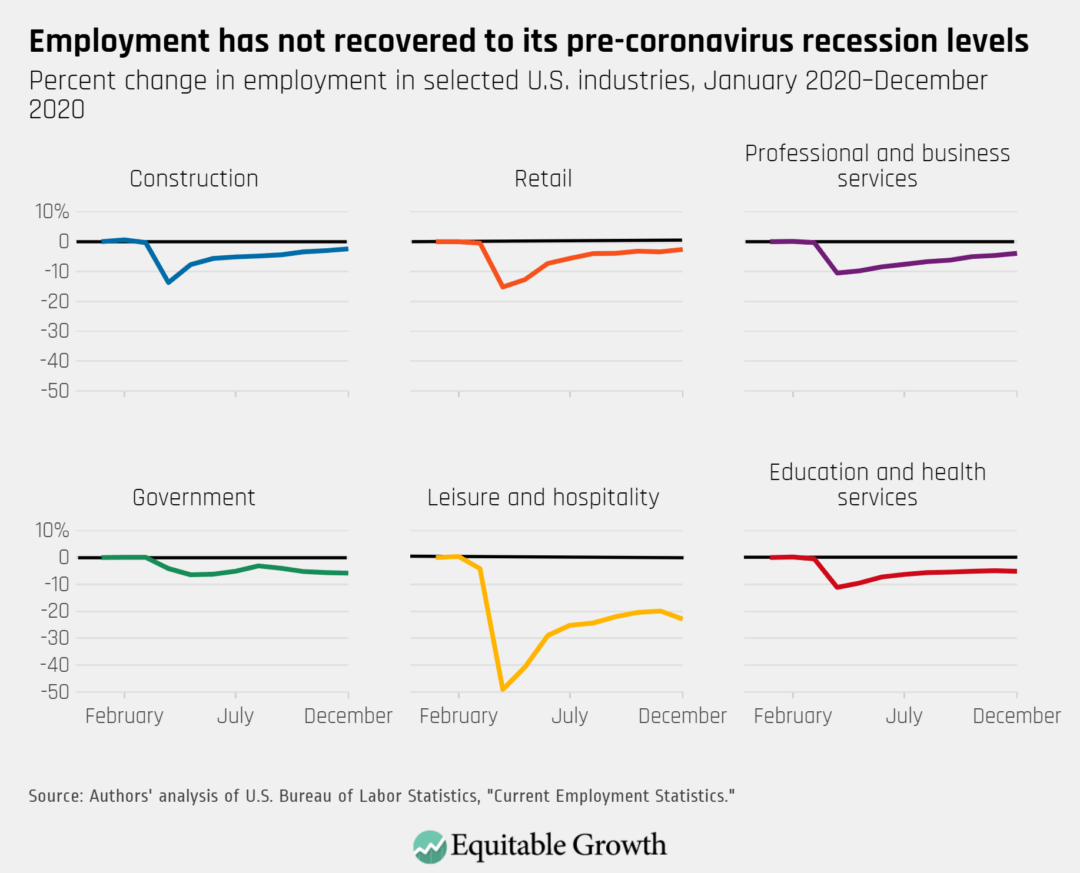

As corporations grow bigger and richer, millions of Americans are still out of work—and new research indicates many of those jobs probably aren’t coming back even after the public health crisis passes. The Washington Post’s Heather Long reports that the pandemic is likely to change the nature of the economy and the labor force, requiring millions of workers to be retrained, recertified, or even shift careers or industries in order to find work. One reason for these permanent job losses, Long continues, could be the increase in automation that usually arises during recessions as employers look to cut costs and experiment with new technology during periods of high unemployment and layoffs. Amid the pandemic, economists predict that these trends could be further amplified as social distancing and other public health and safety measures are enforced to limit the number of people simultaneously working in a single place.

Many Americans who qualify for social safety net assistance do not receive it, or even apply for it, thanks to a complex, outdated system that prevents many from trying to access badly needed aid. Harin Contractor, Jamil Poonja, and Faiz Shakir at Vox outline the deficiencies of the U.S. social safety net to protect vulnerable Americans who are eligible to receive government-provided relief. These holes in the system have become ever more apparent amid the coronavirus pandemic, the co-authors write, and are ever more important to address as Congress and the Biden administration negotiate future coronavirus stimulus. If relief is to be effective and actually help those in need, the co-authors argue, it will be necessary to ensure greater coordination between government aid programs and implementing agencies, and the simplification of benefits and application processes.

Friday figure

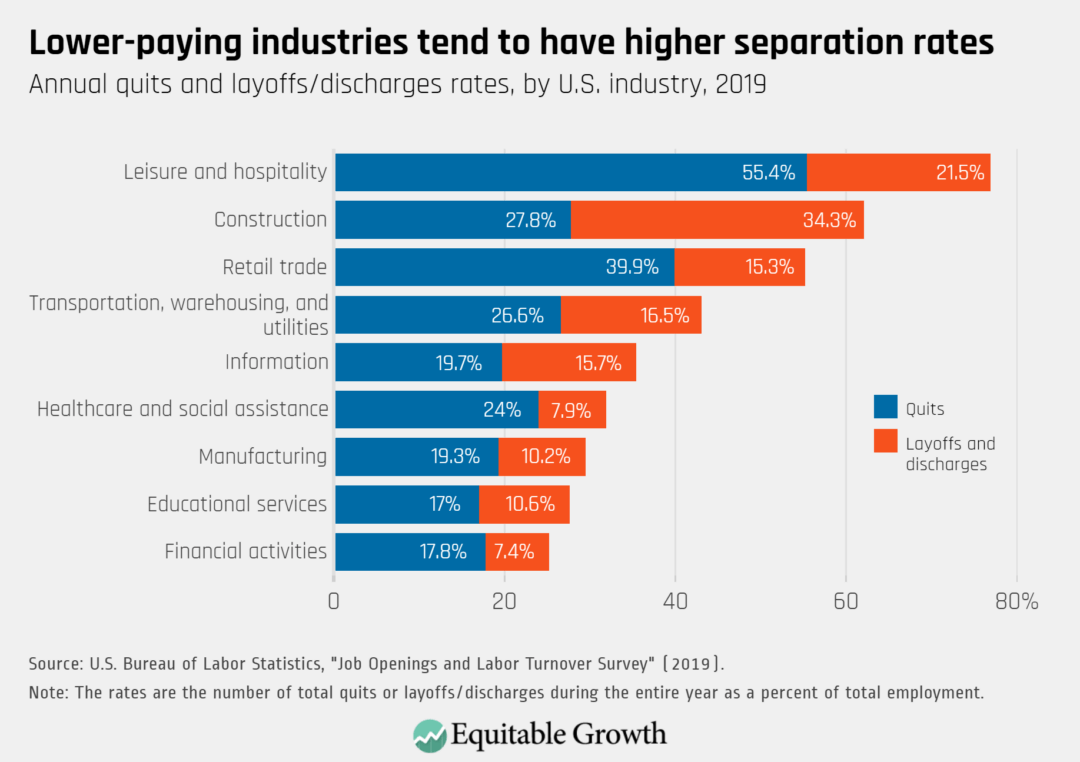

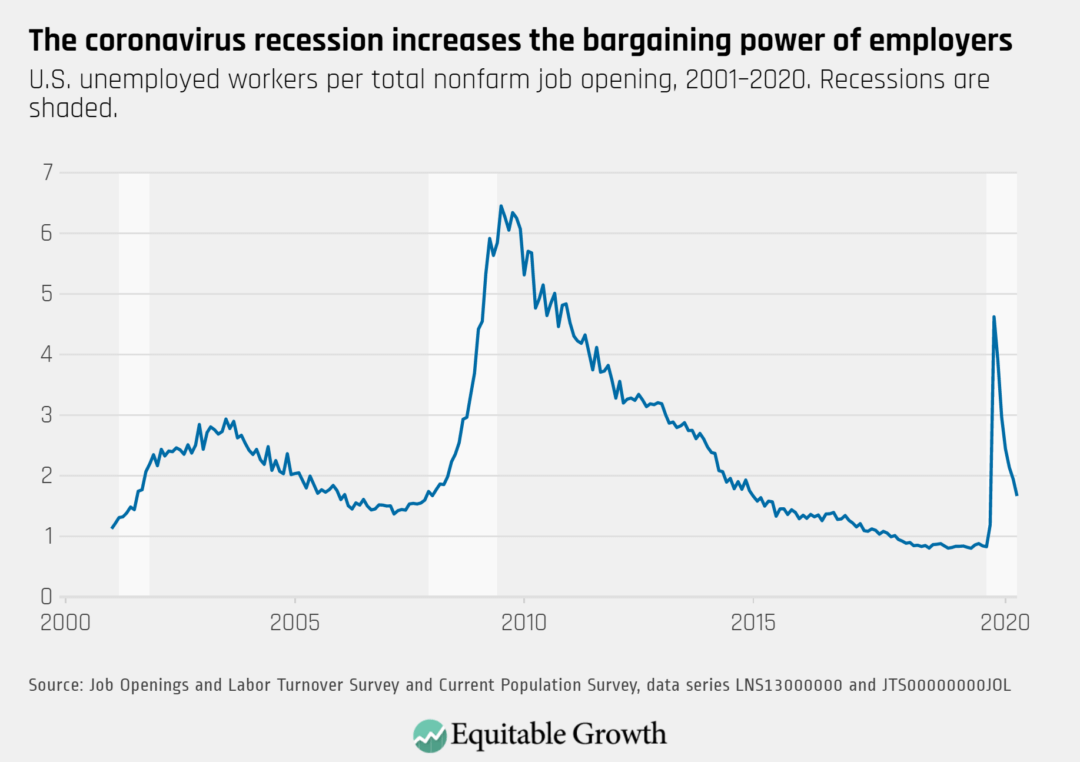

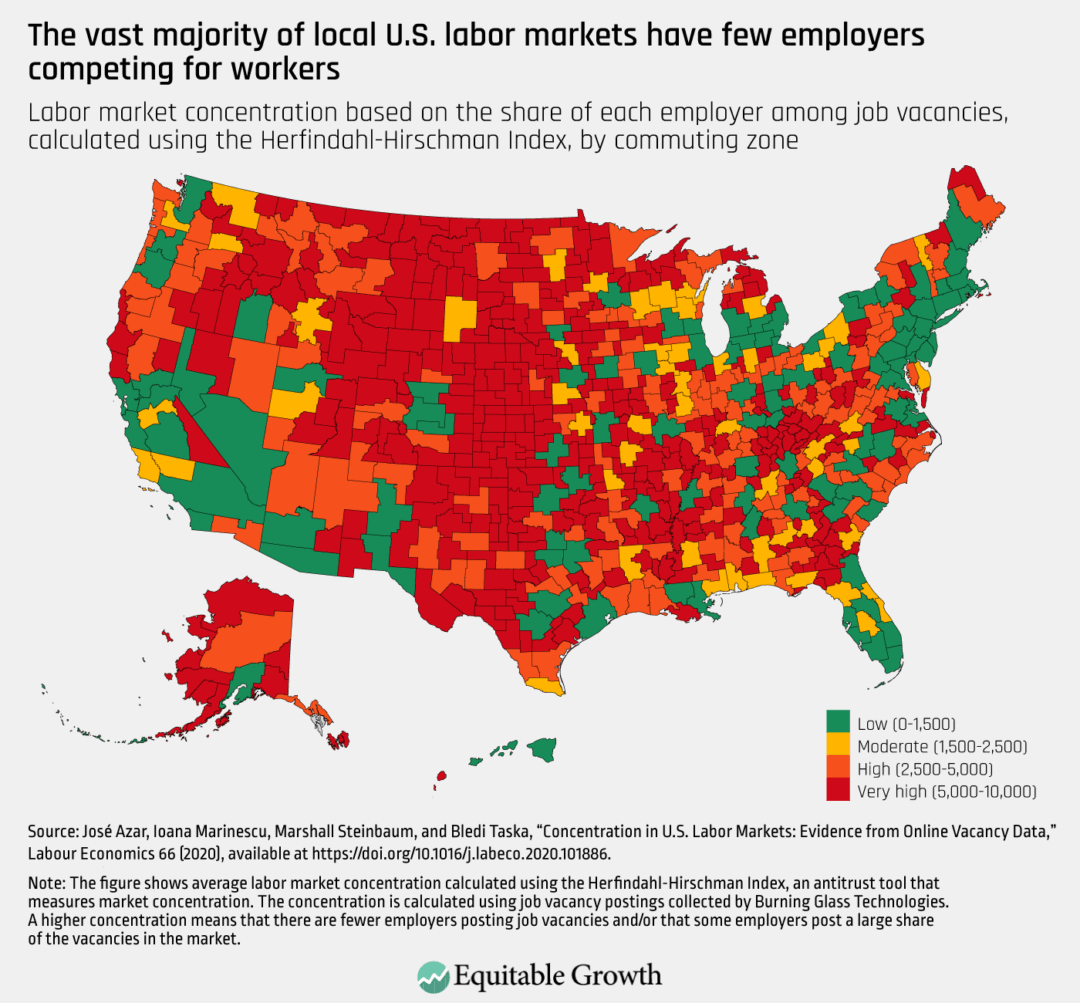

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Boosting wages when U.S. labor markets are not competitive” by Ioana Marinescu.