In 1954, Brown v. Board of Education was the unanimous U.S. Supreme Court ruling that led to the beginning of the end of blatant racial segregation of children in public schools. Actual desegregation took decades to enforce and is still incomplete in many local school districts across the United States. But what’s equally troubling is a new type of segregation in some school districts—gerrymandered school borders that fence out students from economically stressed families, which often means new segregation along racial and ethnic lines.

With economic inequality on the rise sharply over the past four decades, families are increasingly segregated into communities based on income status, resulting in public schools becoming increasingly segregated by income. Research from 2014 Equitable Growth grant recipient Sean Reardon of Stanford University, Christopher Jencks of Harvard University, and Ann Owens of the University of Southern California found that between 1990 and 2010, the segregation of public-school families by income between school districts had increased by more than 15 percent. A separate study by Ann Owens points out that as economic segregation within schools increased, the test score gap between high- and low-income students also increased by nearly 40 percent.

As Owens’ study highlights, neighborhoods determine school districts. As school districts are heavily funded by property taxes, high-income neighborhoods are able to employ better teachers, purchase the newest books, and offer opportunities and extracurricular activities outside of school hours that low-income neighborhoods simply can’t afford. This becomes detrimental, as poor districts often need more financial resources than high-income districts in order to provide lower-performing children with the tools they need to catch up, make improvements to the school’s physical conditions, and bring in higher-quality teachers to address low-performing students’ needs.

This lack of fiscal resources leads to low-income school districts finding it impossible to catch up. Owens’ research finds that even when funding formulas equalize spending, high-income districts’ residents regularly vote to spend more on schooling, adding additional resources to their classrooms while leaving low-income students in outside districts further behind.

There is evidence that some school districts have purposefully gerrymandered district lines to segregate low-income students. A piece from Vox points out that since 2000, more than 70 communities have made attempts to secede from their school districts, two-thirds of which have been successful. As an example, organizers in Gardendale, Alabama seceded from the Jefferson County school district 6 years ago. These organizers made the argument that schools were already overcrowded and underfunded, and that by better controlling the geographic composition of the student body, they would be able to reallocate school resources. As a consequence, they were systematically carving out affluent school districts, leaving low-income students to be redirected to underperforming schools in the area.

But there are solutions. The nonprofit news website The 74 earlier this month examined approaches from school districts that were doing the exact opposite of those in Jefferson County, Alabama. In 2010, for example, the school system in Montgomery County, Maryland, began randomly assigning low-income students to attend low-poverty schools. By the end of elementary school, the county found that students in the experiment had reduced achievement gaps in math and reading compared to their nonpoor classmates and drastically outperformed their peers in low-income schools. In a joint project with Washington Monthly magazine, Equitable Growth also examined Montgomery County’s education reform efforts. The piece found overall that if policymakers “want to really have growth with equity, [then they] should be putting more money and energy into economic integration in schooling and housing.”

Another experiment for integration that came to essentially the same conclusion was in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which the city refers to as “controlled choice.” It converted all of the city’s Kindergarten through eighth grade schools into magnet schools and required parents to rank choices where to enroll their children. The district then placed students into schools with the goal of achieving a balance that resembled the city as a whole based on race and then further went on to integrate schools based on economic status. It found that 90 percent of students still received their top-choice school and today, the school district remains one of the top-performing in the country.

Furthermore, research from Philip Tefeler and Michael Hilton of the Poverty & Race Research Council lays out solutions to the issue based on fairer housing policies. They argue that housing policies have a direct impact on school composition and thus designing these policies to give low-income children of color access to high-performing schools would have the most direct impact on school integration. Key policy recommendations include an expansion of the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, housing voucher policies targeting high-performing, low-poverty schools, mortgage assistance programs that promote school integration, state zoning laws prioritizing school integration, and eliminating tax incentives to reward the purchase of homes in high-income school districts.

In short, by designing housing policies around economic school integration, low-income students would have greater access to these high-performing schools and would work to close the education achievement gaps that persist between low- and high-income students.

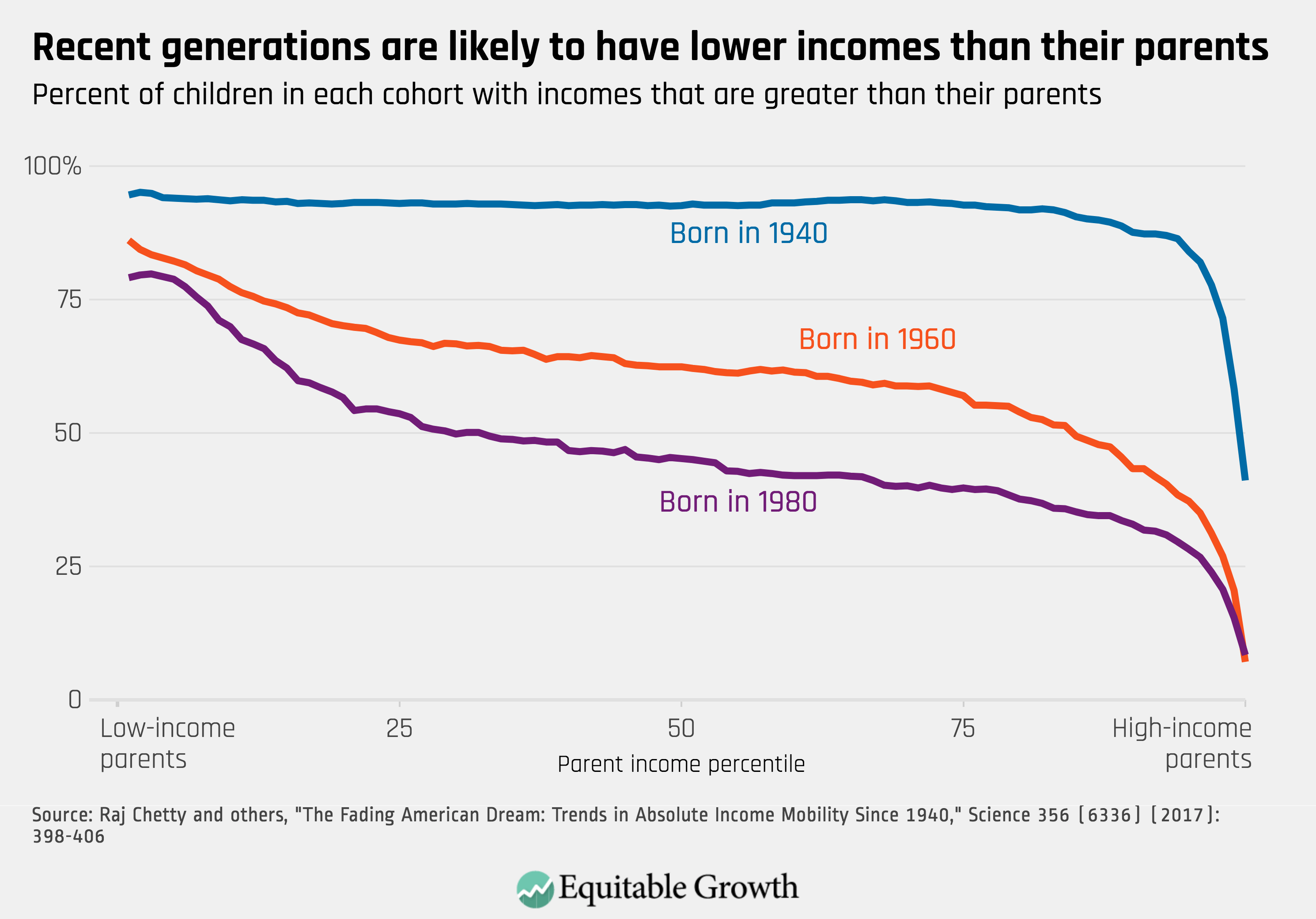

High educational achievements strongly correlate with upward mobility when Kindergarten, primary, and secondary schoolchildren reach adulthood. An individual’s educational success and achievement is a predictor for many adult outcomes, thus, achievement gaps between high- and low-income students may result in greater economic inequality in future outcomes such as employment, income, neighborhood residence, criminality, and health. Research by Stanford’s Reardon and Richard Murane of Harvard University argues that the rising segregation by income of local school districts will lead to a strengthening in the intergenerational transmission of economic inequality and further reduce the potential for upward economic mobility.

These findings strongly suggest that states and localities must do all that they can to ensure not only that students are integrated across racial lines, but also that a diverse array of students from varying economic backgrounds are integrated into school districts. As Equitable Growth’s Heather Boushey put it in her introduction to the Washington Monthly special focus on economic growth and inequality: “This should be the start of a serious discussion in Washington and in statehouses across the country about fresh economic policies—no longer hamstrung by stale arguments about supply-side economics or the welfare state. New economic research on equitable growth is rendering moot the old rhetoric behind political stalemate.”