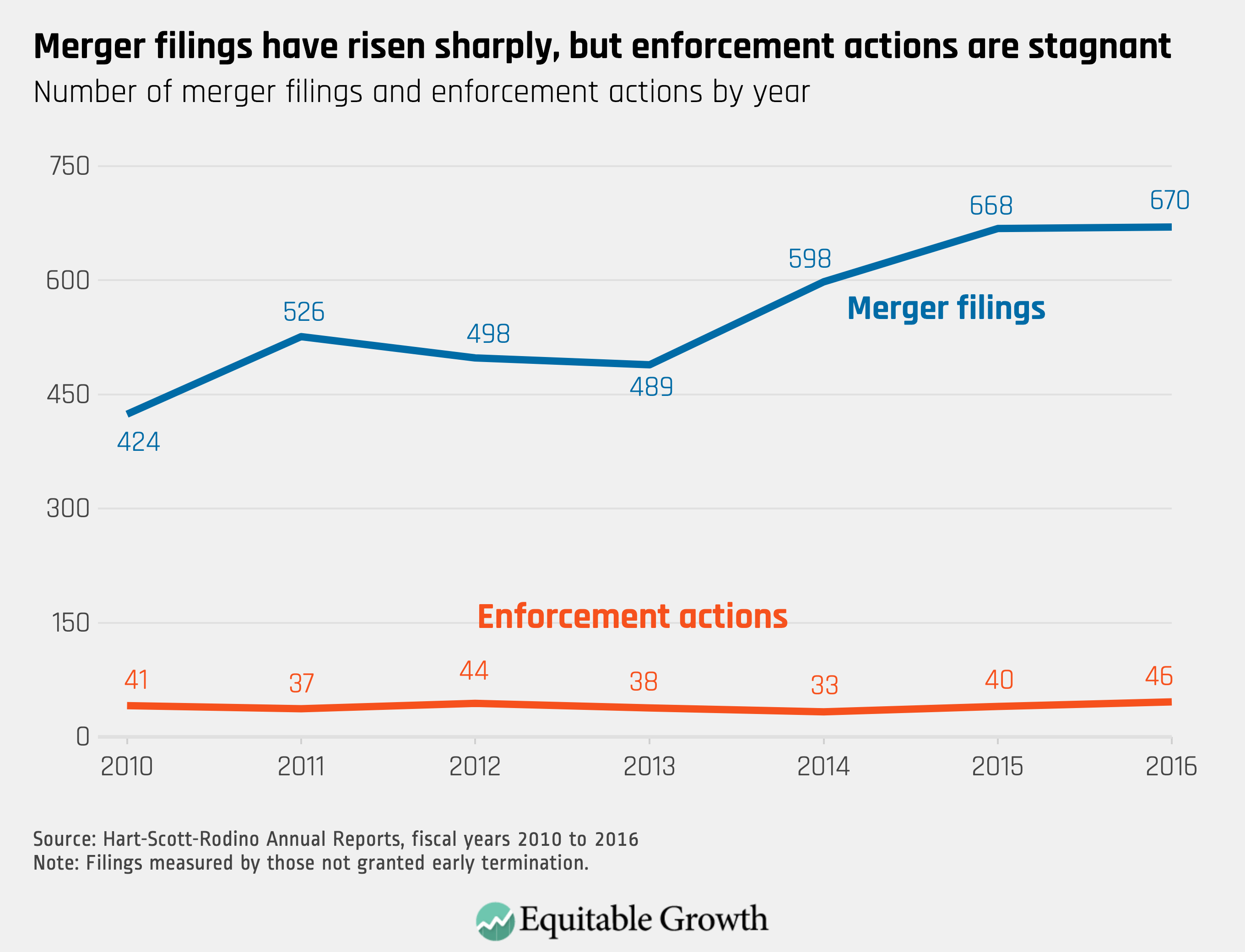

Antitrust and competition issues are receiving renewed interest, and for good reason. So far, the discussion has occurred at a high level of generality. To address important specific antitrust enforcement and competition issues, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth has launched this blog, which we call “Competitive Edge.” This series features leading experts in antitrust enforcement on a broad range of topics: potential areas for antitrust enforcement, concerns about existing doctrine, practical realities enforcers face, proposals for reform, and broader policies to promote competition. Jonathan B. Baker has authored this month’s contribution.

The octopus image, above, updates an iconic editorial cartoon first published in 1904 in the magazine Puck to portray the Standard Oil monopoly. Please note the harpoon. Our goal for Competitive Edge is to promote the development of sharp and effective tools to increase competition in the United States economy.

Growing market power in the United States today puts a spotlight on our nation’s antitrust laws—the critical policy tool for restoring competition where it is lacking—from airlines and brewing to hospitals and dominant online platforms. But how can these laws be made more effective in this environment? The best guide from the past is Thurman Arnold, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s longest-serving antitrust enforcer.

Arnold helped shape a political consensus for effective antitrust enforcement. Yet his singular contribution is often overlooked in the present-day debate over antitrust’s future. That achievement—the embrace of an antitrust enforcement playbook for supervising large firms that is competition-promoting and economic growth-enhancing—is endangered today.

To put Arnold’s achievement in perspective, let me briefly summarize more than a century of U.S. antitrust history. For decades after 1890—the year Congress enacted the Sherman Antitrust Act—antitrust laws were enforced inconsistently, and government policy toward large firms was the subject of bitter political debate. That changed after Arnold took the helm of the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division toward the end of the New Deal, and the so-called structural era of U.S. antitrust history began to take shape. The strong rules put in place beginning in the 1940s were relaxed in the late 1970s and 1980s, when antitrust doctrine entered its “Chicago school” era, named after the conservative proponents of this new approach who were associated with the University of Chicago.

To a considerable extent, the present-day debate over antitrust’s future is tied to competing accounts of what happened in the 1940s and 1980s. Progressives emphasize the ideas of antitrust advocate and Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, while conservatives highlight the views of Chicago alumnus, law professor, and appellate Judge Robert Bork. Both narratives neglect Arnold’s critical achievement and relevance for the current debate.

A prominent progressive account interprets the tough antitrust rules put in place during the structural era, including their hostility to all but the smallest mergers, as a triumph for Brandeis snatched away three decades later by Bork. In this story, economic policy in the 1940s represents what Progressive era reformers would call a victory of “the people” over “the interests.” In this view, after decades of bitter political debate over the role of large firms in the U.S. economy—what Brandeis termed a “curse of bigness”—was checked by antitrust and regulation.

This progressive narrative assimilates the development of modern antitrust doctrine into a broader chronicle of 20th century progressive political achievements that also features an expansion of political rights, greater inclusion of historically disadvantaged groups into mainstream political and economic life, and increased economic security for the less fortunate.

There is a basis for this narrative. Mid-20th century courts saw antitrust laws as advancing social and political goals—particularly Brandeisian concerns to protect democracy from the outsized influence of concentrated economic power and to ensure an opportunity for small businesses to compete—along with pursuing economic goals such as preventing firms with market power from exploiting consumers and other victims. Occasionally, monopolies were broken up. In much of the communications, energy, financial services, and transportation industries, direct economic regulation of big business, another of Brandeis’ enthusiasms, supplanted and supplemented antitrust law.

The competing conservative account interprets the 1940s very differently. The Chicago school maintains that populist antipathy to big business was taken too far, but thankfully corrected beginning in the late 1970s. In this view, Chicagoans such as Bork preserved economic vitality by freeing markets from excessive antitrust enforcement and economic regulation.

There is a basis for this narrative, too. In response to the Chicago critique, even proponents of robust antitrust enforcement such as Robert Pitofsky acknowledged that the mid-20th century antitrust rules had chilled the pursuit of efficiencies, and that some change of course would be beneficial.

Yet both the progressive and conservative accounts leave out an important factor. It is a mistake to view antitrust policy as simply a contest between Brandeis and Bork over whether competition policy should tilt toward consumers, workers, and farmers, on the one hand, or big business on the other. A third and better interpretation understands 1940s antitrust as something new—the reflection of an informal political consensus that rejected extensive economywide economic regulation, on the one hand, and laissez-faire deregulation on the other—in favor of close scrutiny of the competitive implications of the conduct of large firms in concentrated markets.

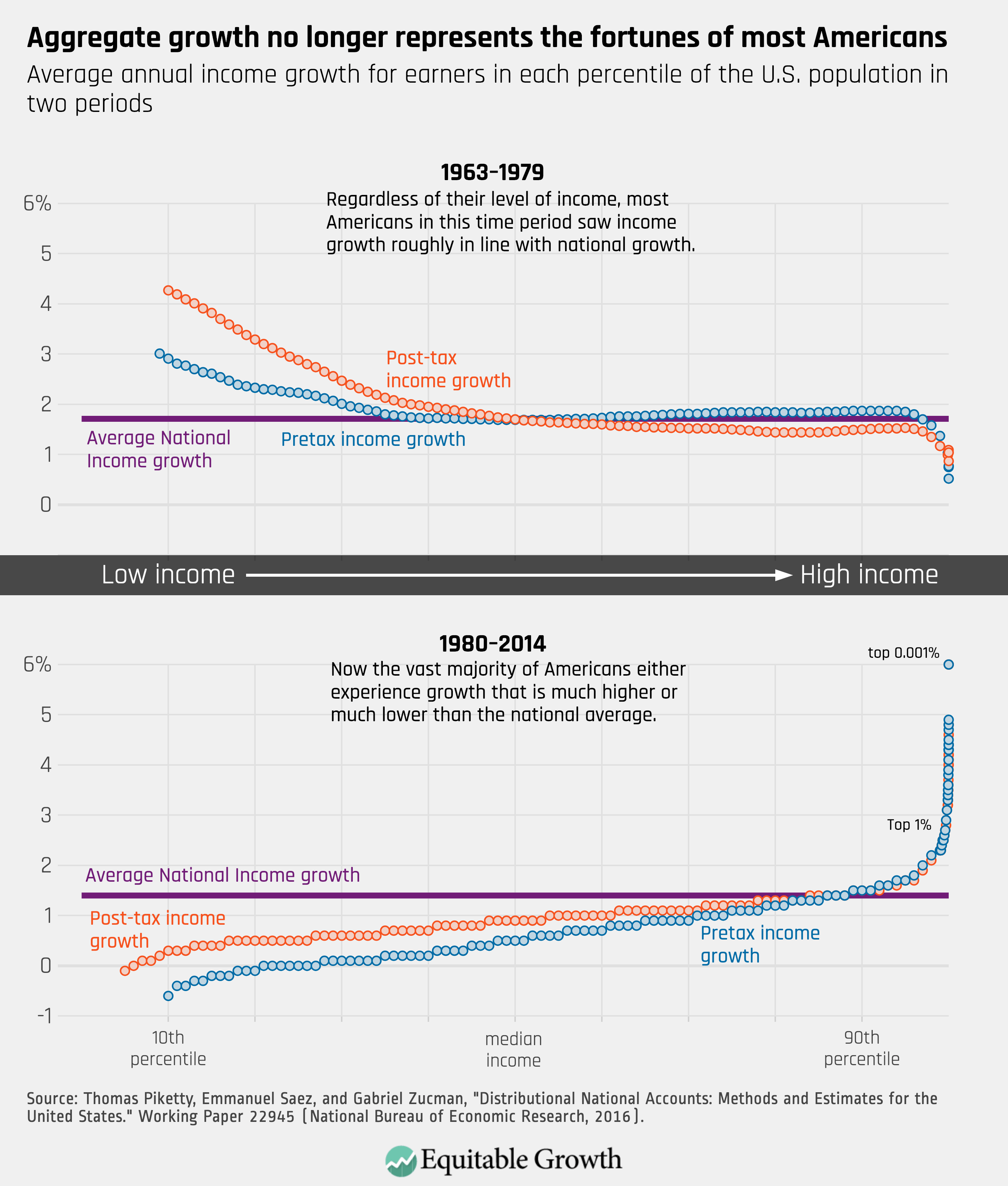

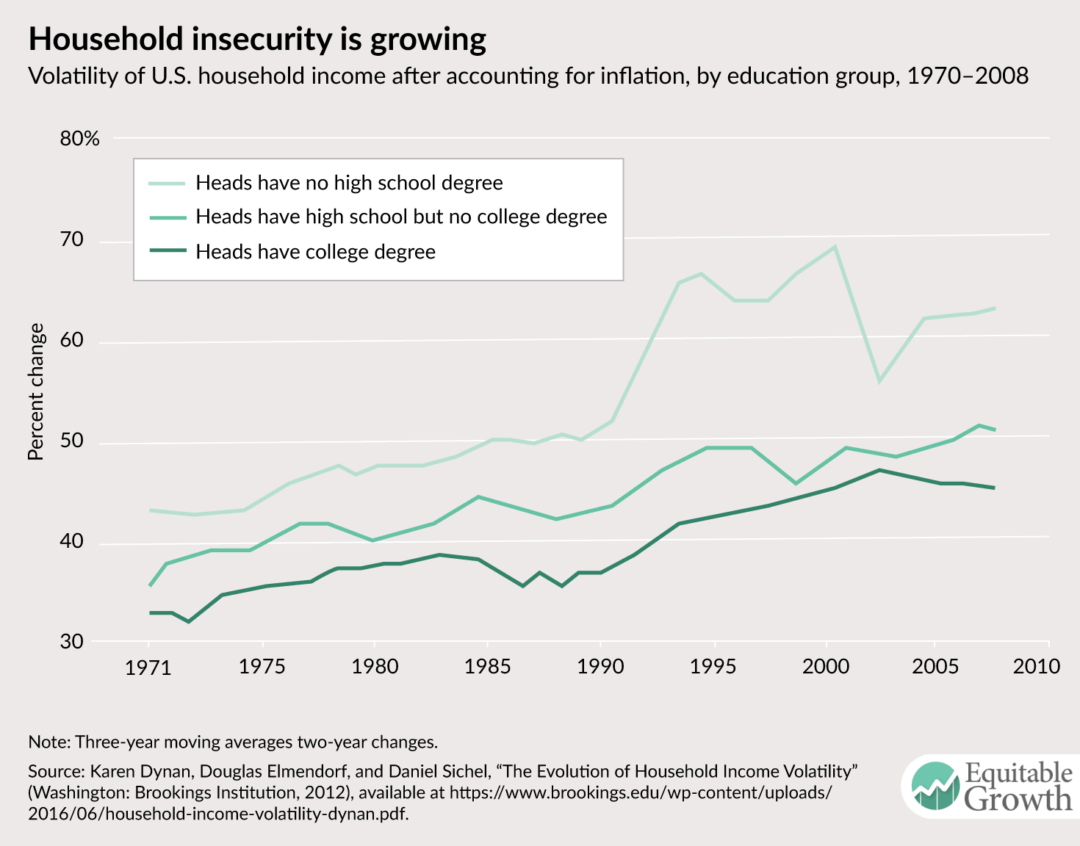

This informal political consensus meant that antitrust law became a positive-sum policy, focused on fostering economic growth and productivity rather than just a zero-sum distributional choice. That consensus was politically acceptable so long as the gains from making markets competitive were shared across the economy.

Thurman Arnold helped give birth to this new approach as the leader of the Department of Justice Antitrust Division from 1938 through 1943. Arnold ramped up enforcement, but his program was not a Brandeisan mix of deconcentration and regulation. “Unlike the Brandeisians,” the historian Ellis Hawley wrote, “Arnold never seemed greatly concerned about the mere possession of economic power or the social evils of bigness per se.” Arnold accepted that large firms were desirable “as long as they were efficient and passed along the savings to consumers.”

Arnold targeted industrywide problems with multiple lawsuits, which were often resolved through consent settlements. He also urged the courts to enforce tough checks on the anticompetitive conduct of large firms in concentrated markets. Arnold’s approach was ratified in key judicial decisions governing price-fixing and monopolization and by Congress when it enacted new merger legislation. “By linking antitrust to consumer interests, and in defining consumer interests as he did,” biographer Spencer Weber Waller explains, “Arnold set the stage for modern antitrust.”

Achieving the consensus that Arnold brokered was far from inevitable. For decades, political conflict over the role of large firms in the economy seemed impossible to resolve. The recognition that the U.S. political system reached an informal bargain explains why political conflict over large firms died down after the 1940s, to the point where historian Richard Hofstadter, writing in 1964, described antitrust as “one of the faded passions of American reform.”

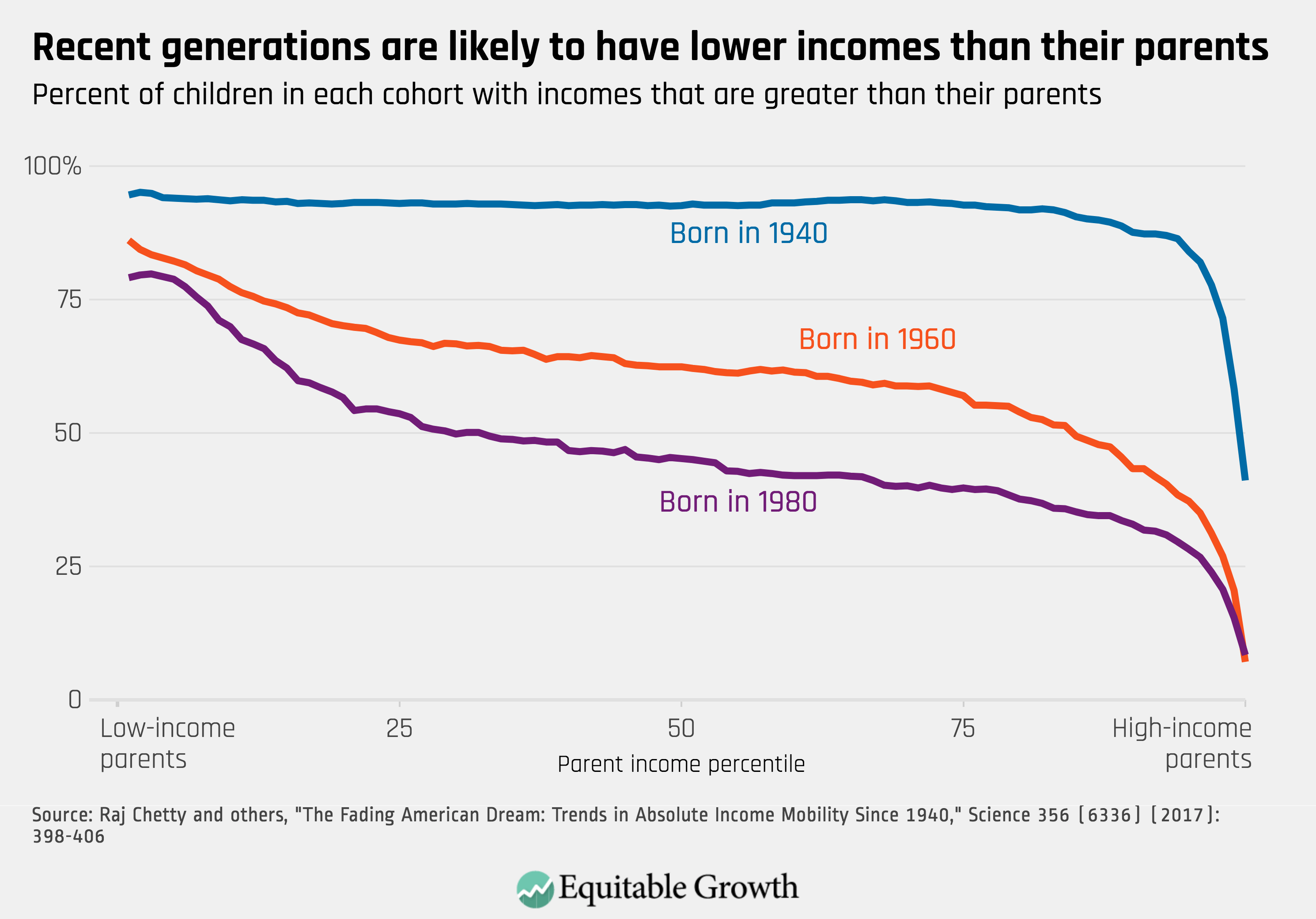

The benefits of antitrust enforcement as an alternative both to widespread economic regulation and to the threat of market power posed by laissez-faire economic policies have long been understood, but the full import of Arnold’s accomplishment has not been widely recognized. Modern antitrust law is a neglected but highly consequential achievement of the World War II generation. The achievement stands alongside more heralded developments in economic policy, particularly international economic institutions and social safety net policies, in helping to construct a society that captured and shared broadly the benefits of economic growth. These developments collectively supported the American Dream of greater economic opportunity and better living standards.

From this perspective, the reworking of antitrust law that began in the late 1970s was a response to the economic problems of that later period—a reworking that sought to improve antitrust enforcement without rejecting the hard-won political consensus achieved decades earlier. Bork and the Chicagoans bet that greater efficiencies from relaxing antitrust rules would more than compensate for the increased risk that firms would exercise market power.

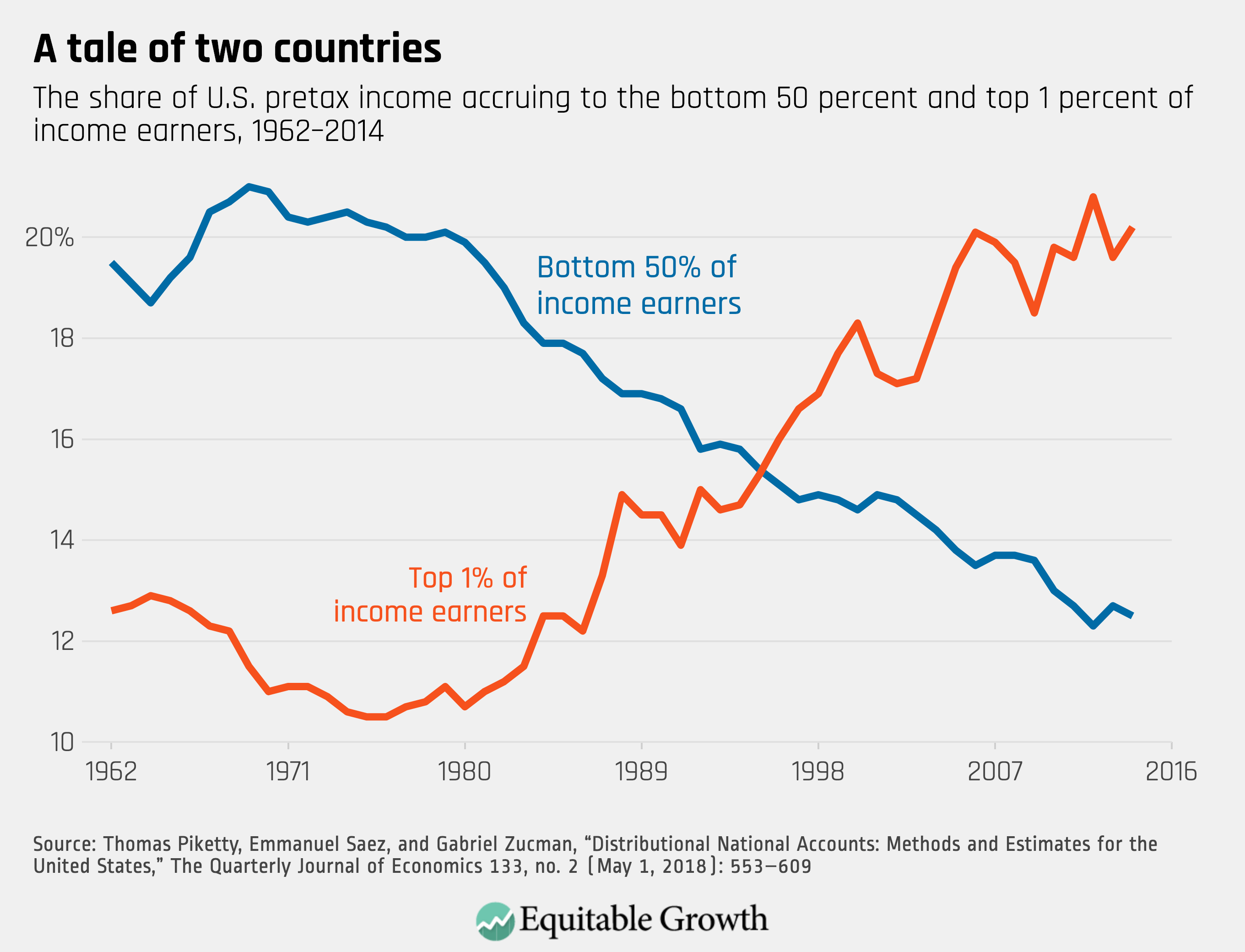

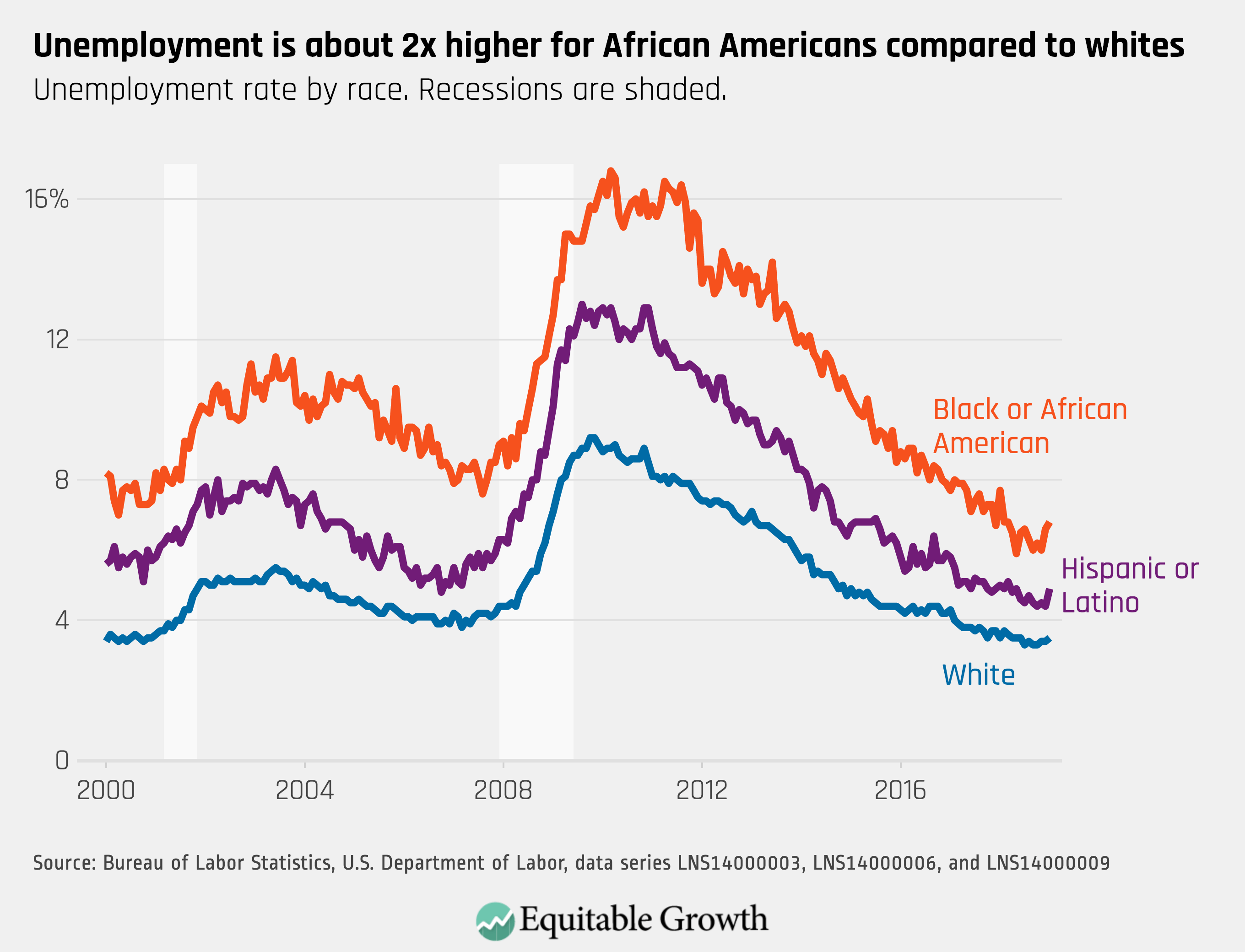

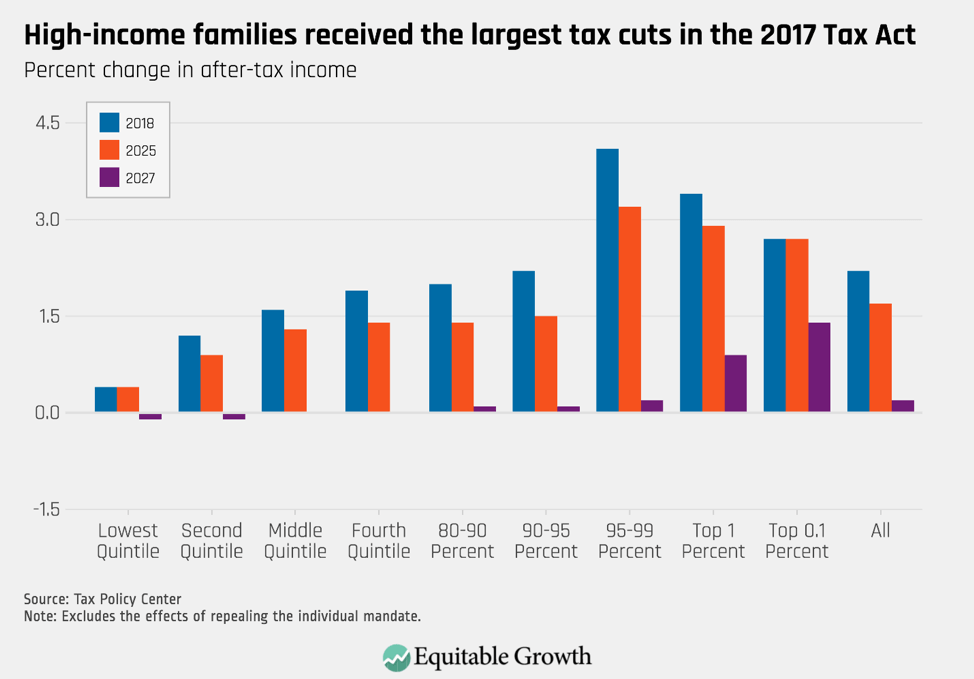

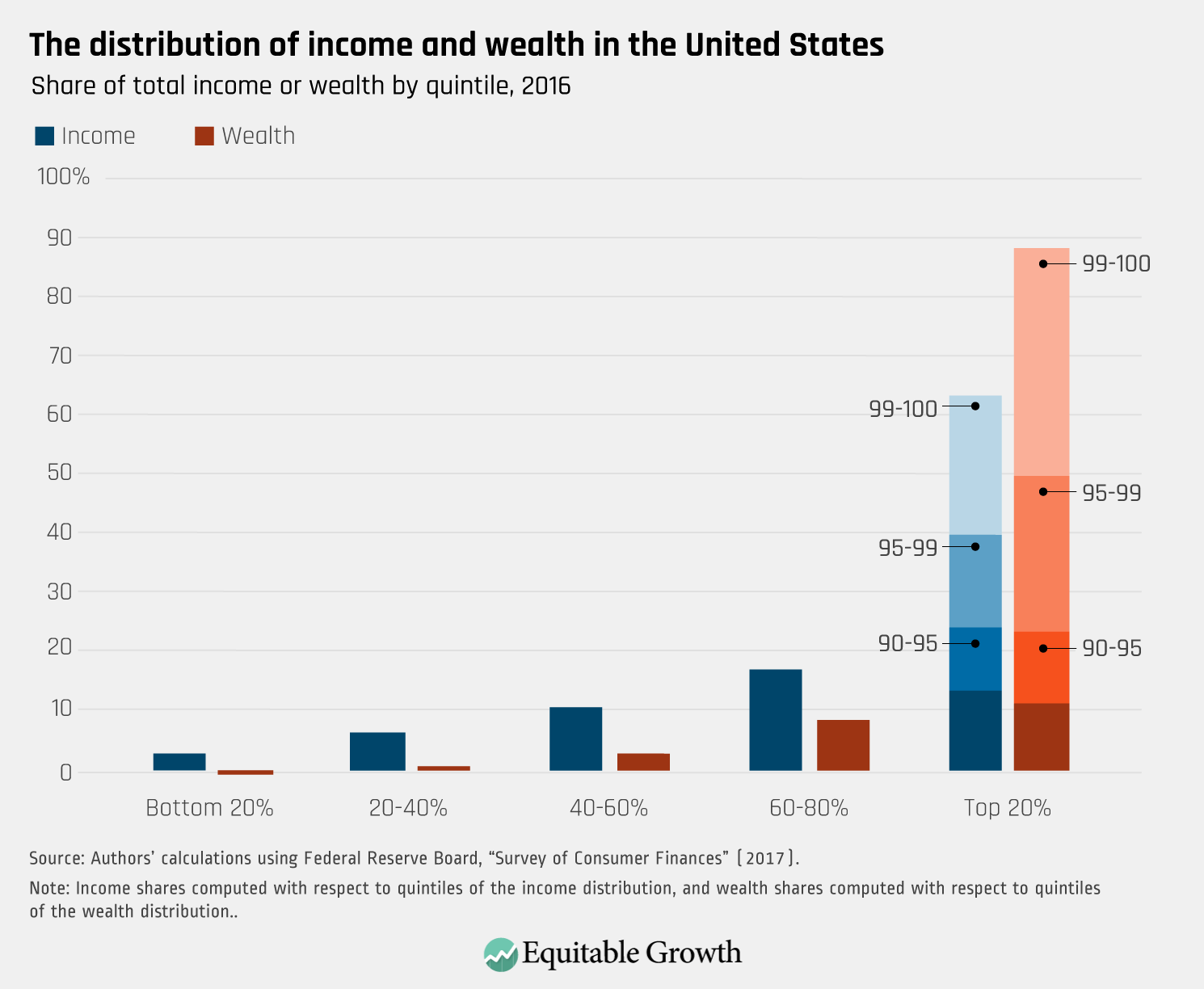

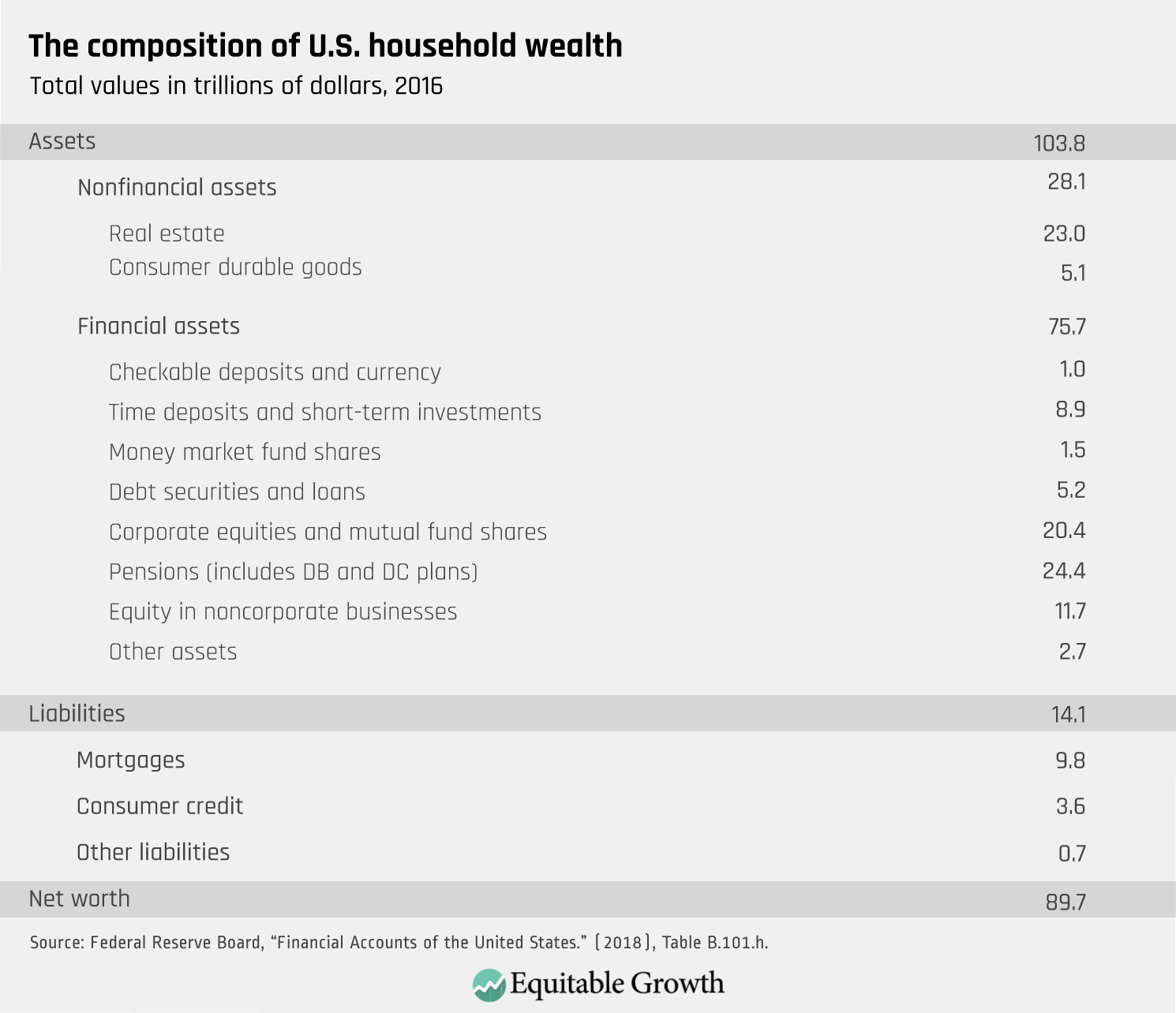

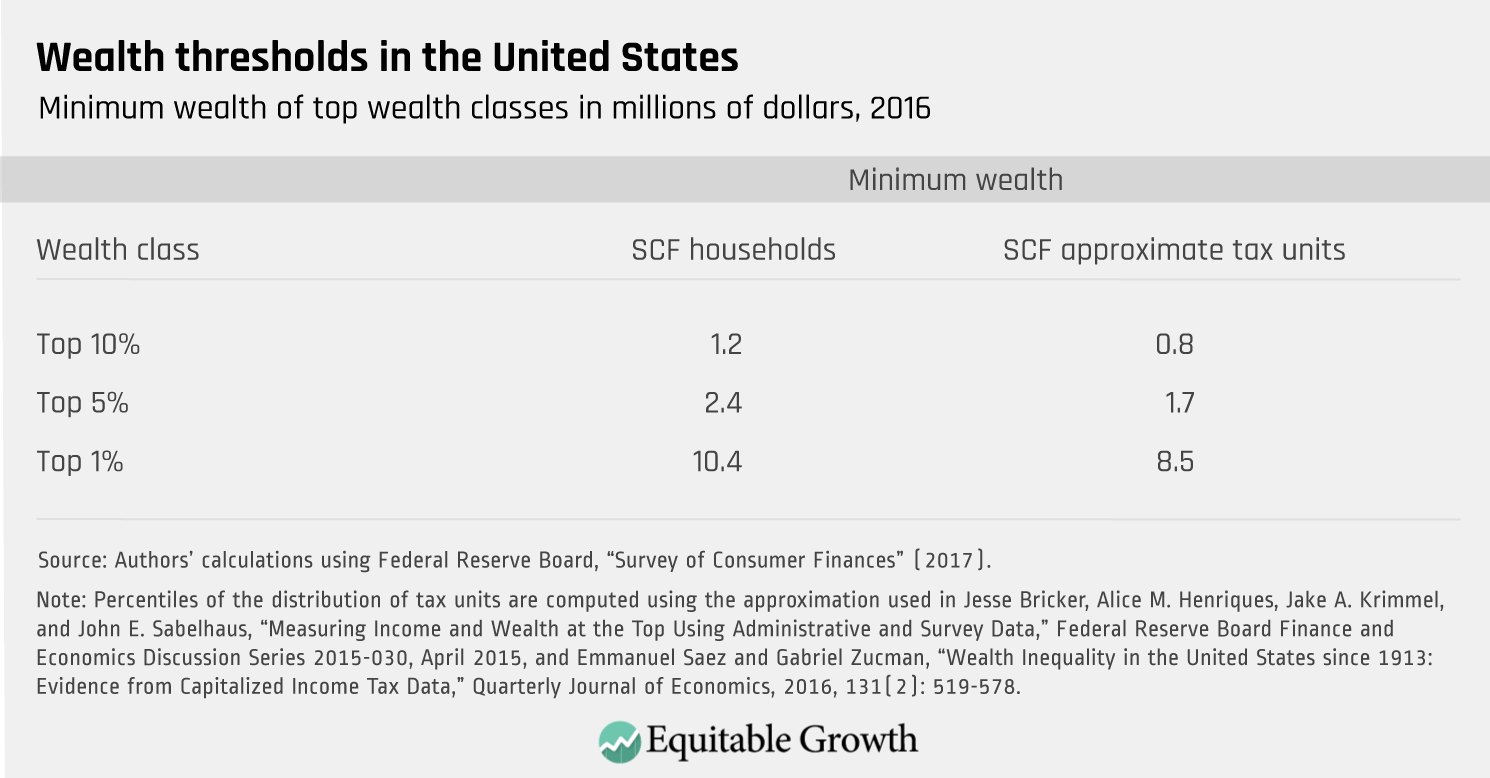

We now know that the Chicagoans lost their bet. Since the implementation of Chicago-inspired antitrust deregulation, market power has widened but without accompanying long-term economic welfare gains. Instead, economic dynamism and the rate of productivity growth have been declining, and growing market power has contributed to a skewed distribution of wealth.

With the benefit of hindsight, it is evident that the Chicago-oriented antitrust rules are not up to the task of controlling market power. Beyond the direct economic harms, the greater the license to exercise market power accorded to big businesses, the greater the threat that the political consensus for modern antitrust enforcement, formed in the 1940s, will collapse—setting up a divisive political choice between laissez-faire economic policies and an extensive regulatory response. Whichever side wins, this political conflict would be a setback. It would mark the end of Arnold’s competition-promoting and economic growth-enhancing approach to supervising large firms.

Arnold’s accomplishment teaches that without broad political acceptance, antitrust law cannot succeed in sustaining shared economic growth by fostering competition. Growing market power now threatens to undermine political support for antitrust enforcement, and with it, a notable achievement of Arnold and the Greatest Generation. To protect that achievement, restore competition, and help revitalize the American Dream, we must strengthen antitrust rules today.

Restoring competition requires stronger antitrust rules than those adopted four decades ago. The Chicago era rules have failed to deter anticompetitive conduct adequately, in part because they rely on what turned out to be erroneous assumptions about markets and institutions. But restoring competition does not mean returning to the rules established in Arnold’s time. The structural era rules were not created for an information technology economy, and their revival would excessively chill efficiencies.

Instead, enforcers and courts should bring modern economic thinking to bear. A recent collection of articles in The Yale Law Journal and my forthcoming book rely on economic analysis to identify enforcement initiatives to pursue and presumptions to adopt to make antitrust more effective in controlling market power. With modern economics as a guide, antitrust can restore a competitive economy.

—Jonathan B. Baker is a research professor of law at American University’s Washington College of Law. He is the author of the forthcoming book The Antitrust Paradigm: Restoring a Competitive Economy.