Competitive Edge: Protecting the “competitive process”—the evolution of antitrust enforcement in the United States

Antitrust and competition issues are receiving renewed interest, and for good reason. So far, the discussion has occurred at a high level of generality. To address important specific antitrust enforcement and competition issues, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth has launched this blog, which we call “Competitive Edge.” This series features leading experts in antitrust enforcement on a broad range of topics: potential areas for antitrust enforcement, concerns about existing doctrine, practical realities enforcers face, proposals for reform, and broader policies to promote competition. Jonathan Sallet has authored this month’s contribution.

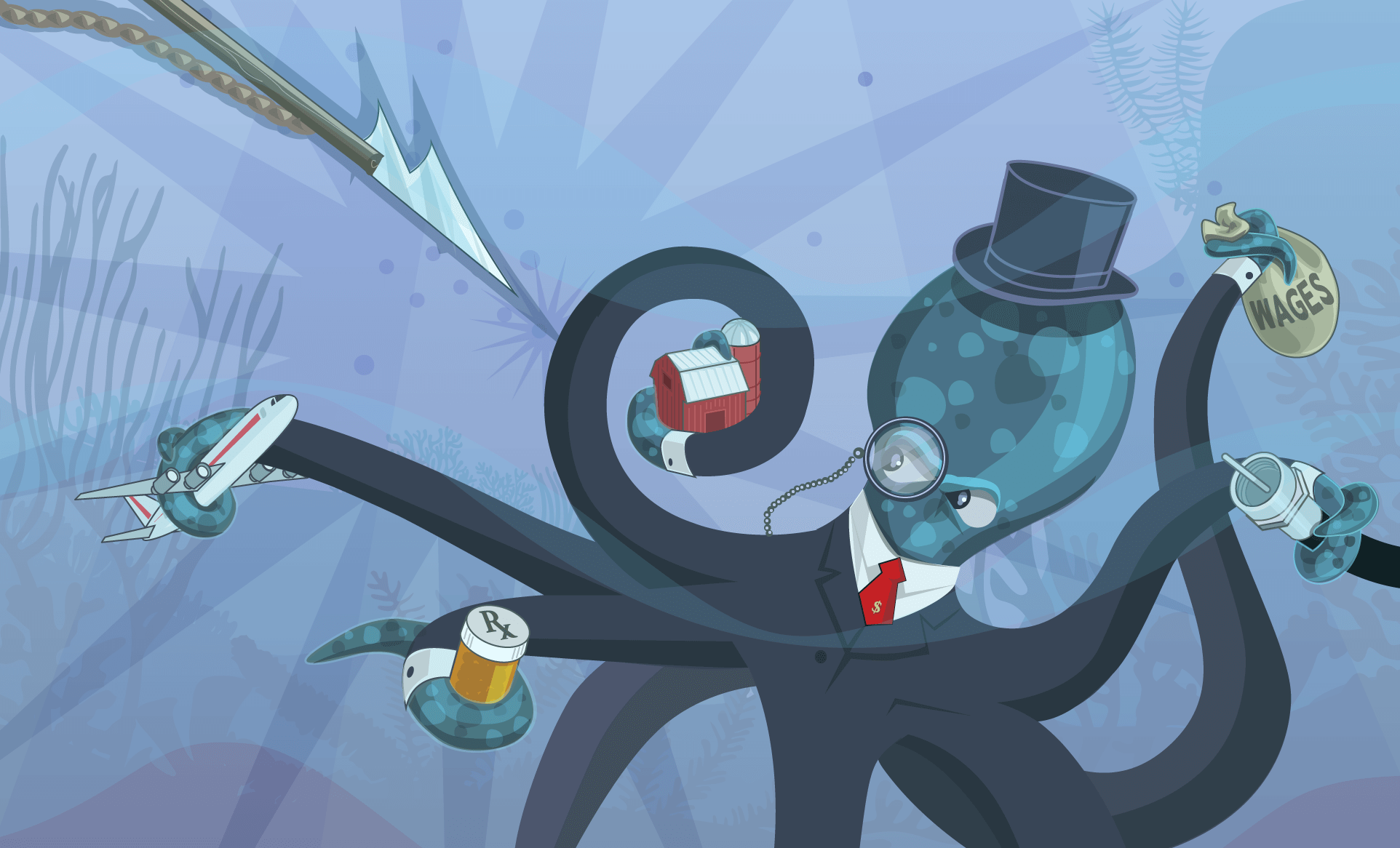

The octopus image, above, updates an iconic editorial cartoon first published in 1904 in the magazine Puck to portray the Standard Oil monopoly. Please note the harpoon. Our goal for Competitive Edge is to promote the development of sharp and effective tools to increase competition in the United States economy.

The Federal Trade Commission this week tackles a central question of competition: Are the goals of antitrust enforcement in the United States best pursued by applying what’s known as the consumer welfare standard?

Over the past forty years, the consumer welfare standard has become closely associated with the so-called “Chicago School” of antitrust doctrine—named after the scholarship centered at the University of Chicago—a central theme of which is that a monopoly is unlikely to cause harm to consumers, either through vertical integration (the merger of companies at different points in the production process) or exclusionary conduct (for example, the kind of actions at issue in the Microsoft case that enabled the company to maintain its monopoly). Indeed, the view that monopolies will seldom if ever harm consumers rests uneasily in the context of a body of law given the name “anti-trust” precisely because the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was designed to combat trusts, the giant monopolies of the late 19th century and early 20th century.

At various points, the Chicago School has been invoked by those arguing that antitrust should focus on short-term price effects or that monopoly power will inevitably be disturbed by future competition or that foreclosure is unlikely or that vertical mergers will always (or almost always) benefit competition. And the influence of the Chicago School on the application of antitrust law over the past four decades has been extremely significant.

So the question remains: What does it mean just to safeguard “consumer” welfare?

From its inception, the term has been surrounded by uncertainly, in part because the influential Chicago-School jurist and former Solicitor General of the United States Robert Bork himself thought that competitive effects should look beyond consumers to what economists label “total welfare” or the overall value produced by a particular market’s organization, independent of the specific way that gains or losses to individual firms are distributed. And now, the term is under attack. Barry Lynn of the Open Markets Institute urges the two antitrust agencies of the federal government, the Federal Trade Commission and the U.S. Department of Justice’s antitrust division, to formally abandon the consumer-welfare approach, partly because of the evidence he believes demonstrates increased market concentration in the U.S. economy.

This week, the Federal Trade Commission will hear leading scholars both defend the consumer welfare standard and suggest alternative formulations. What is striking about the alternatives being offered is how closely they group around a focus on the “competitive process.” So, for example, Carl Shapiro from the University of California–Berkeley’s Hass School of Business will offer “The Protecting Competition Standard,” under which “a business practice is judged to be anti-competitive if it harms trading parties on the other side of the market as a result of disrupting the competitive process.” This approach, he explains, broadens the central idea behind the consumer welfare standard to account for trading parties other than final consumers, while incorporating both economics and evidence to strengthen antitrust enforcement.

Using similar language, Columbia Law School professor Tim Wu argues for the “protection of competition” as an approach that better orients antitrust enforcement toward “protecting a competitive process that actually rewards firms with better products.” And University of Tennessee law professor Maurice Stucke and his co-author Marshall Steinbaum at the Roosevelt Institute have proposed the use of a new “effective competition” standard, along with legislative changes to effectuate it, noting that “competition policy is principally concerned about promoting a competitive process.” (Barry Lynn and I are both among the other presenters on this question.)

But what difference does a change in terminology make? After all, antitrust specialists generally recognize that antitrust is not limited to short-term price impacts. And the importance of the competitive process has been recognized. For example, the D.C. Circuit’s Microsoft decision emphasized the importance of the competitive process when it explained that antitrust law “directs itself not against conduct which is competitive, even severely so, but against conduct which unfairly tends to destroy competition itself.”

That said, antitrust litigation can be complicated. In front of a generalist judge, government enforcers rightly bear the burden of persuasion—they need not bear an unnecessary burden of explanation.

There are important circumstances in which the term “consumer welfare” can cause unnecessary confusion. Consider carefully the emphasis by UC Berkeley’s Shapiro on harm to “trading parties.” From the perspective of a seller, that means consumers. But from the perspective of a powerful buyer, it means upstream sellers—think of a sawmill that buys the output of logging operations. Or consider employers that agree not to compete against each other for the “purchase” of labor, a practice the two federal antitrust agencies have said will be subject to criminal prosecution as the flip side of an agreement among sellers to fix prices. The workers who are harmed may not be the consumers of those employers but they are “sellers” who, along with the competitive process, have been harmed.

Buyer power (which does not always require monopsony—the flip side of monopoly) is getting increased attention, which adds to the importance of providing a clear picture of potential competitive effects. Last month, the Federal Trade Commission held a hearing on just this issue, and earlier in the year noted antitrust scholar Herb Hovenkamp, the James G. Dinan University Professor at the University of Pennsylvania Law School and Wharton School, in a paper with co-author Ioana Marinescu, professor of economics at the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Policy & Practice, focusing on mergers impacting labor markets and positing that “the antitrust law against anticompetitive mergers affecting employment markets is certainly underenforced, very likely by a significant amount.”

So, for example, during the Department of Justice’s challenge to the merger of healthcare insurers Anthem Inc. and Cigna Corp., the antitrust division’s buyer-power claim (which was not ruled on by the district court) ran headlong into assertions that no problem could exist if that greater buyer power translated into lower prices to customers. But, argue Scott Hemphill of New York University’s School of Law and economist Nancy Rose of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in a recent article in The Yale Law Journal, “the proper focus is harm to sellers.”

Consider also mergers of so-called intermediate buyers—companies that buy from upstream providers and sell to consumers. Such mergers can harm competition because of their effect on, for example, restaurants buying from food-distribution companies, as in the proposed merger between Sysco Corp. and U.S. Foods Holding Corporation that the Federal Trade Commission successfully blocked. In that case, the district court expressly recognized competitive effects on customers “ranging from the corner diner to hospital and nursing home cafeterias to hospitality venues.”

Against this, it could be argued that current law does the job. After all, the Federal Trade Commission won a preliminary injunction in the Sysco case. And U.S. Assistant Attorney General of the Antitrust Division, Makan Delrahim, recently invoked a complaint filed by the Department of Justice in 2016, asserting that information-exchange among prospective buyers of the Dodgers Channel in Los Angeles “deprived LA area Dodgers fans of a competitive process.”

But, from a litigator’s perspective, the use of the term “consumer welfare” injects issues into such cases that threaten confusion without advancing understanding. The importance of considering practical litigation impact was identified by Equitable Growth’s Michael Kades in the September 21st FTC hearing, when he emphasized that if the government has to continually prove basic facts in every case and even the easiest cases are hard, then antitrust laws are failing to protect competition. The continuing confusion about the role of consumers in cases where anti-competitive effects are focused on other traders or the impact of exclusion is defended on the ground that competitors are not consumers helps demonstrate that the “competitive process” better describes the inquiry at hand.

Legal phrases are not talismanic. The application of any formulation requires hard work, a close eye on evidence, and continued attention to competitive effects. But it is notable that this week leading antitrust scholars will focus us on protecting the competitive process as the next step in the evolution of antitrust.

—Jonathan B. Sallet is a senior fellow at the Benton Foundation and previously general counsel of the Federal Communications Commission and deputy assistant attorney general in the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice.