This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Weekend Reading is back, after a few weeks off! We hope you had a wonderful holiday season and wish you the best in 2020.

Given the nature of politics these days, it was a nice surprise that right before Christmas Congress passed and President Donald Trump signed into law historic, bipartisan legislation that will lower prescription drug prices. The measures were folded into the year-end omnibus spending bill, and will strengthen market competition in the industry by limiting the various tactics, including sample blockades and safety protocol filibusters, which drug companies use to prevent generics from entering the market. Michael Kades explains how the pharmaceutical industry uses these tactics to keep competition at a low, and discusses how the new CREATES Act targets these practices specifically in order to lower prices for consumers.

Equitable Growth’s academic grants program is now entering its seventh year. Since 2014, we have provided grants to more than 200 researchers, and distributed more than $5.6 million in grants. We recently wrote up a report covering what we’ve learned from researchers over the past six grantgiving cycles, as well as our new lines of inquiry for this coming year. (And don’t forget to check out our 2020 RFP and 2020 RFP specifically for paid family and medical leave research!)

Last week, Equitable Growth staff attended, spoke at, and co-organized a panel at the American Economics Association’s Allied Social Science Associations annual meeting in San Diego. The three-day event brings together more than 13,000 of the best minds in economics to network and celebrate new achievements in their lines of research. Read our coverage from day one, day two, and day three of the event.

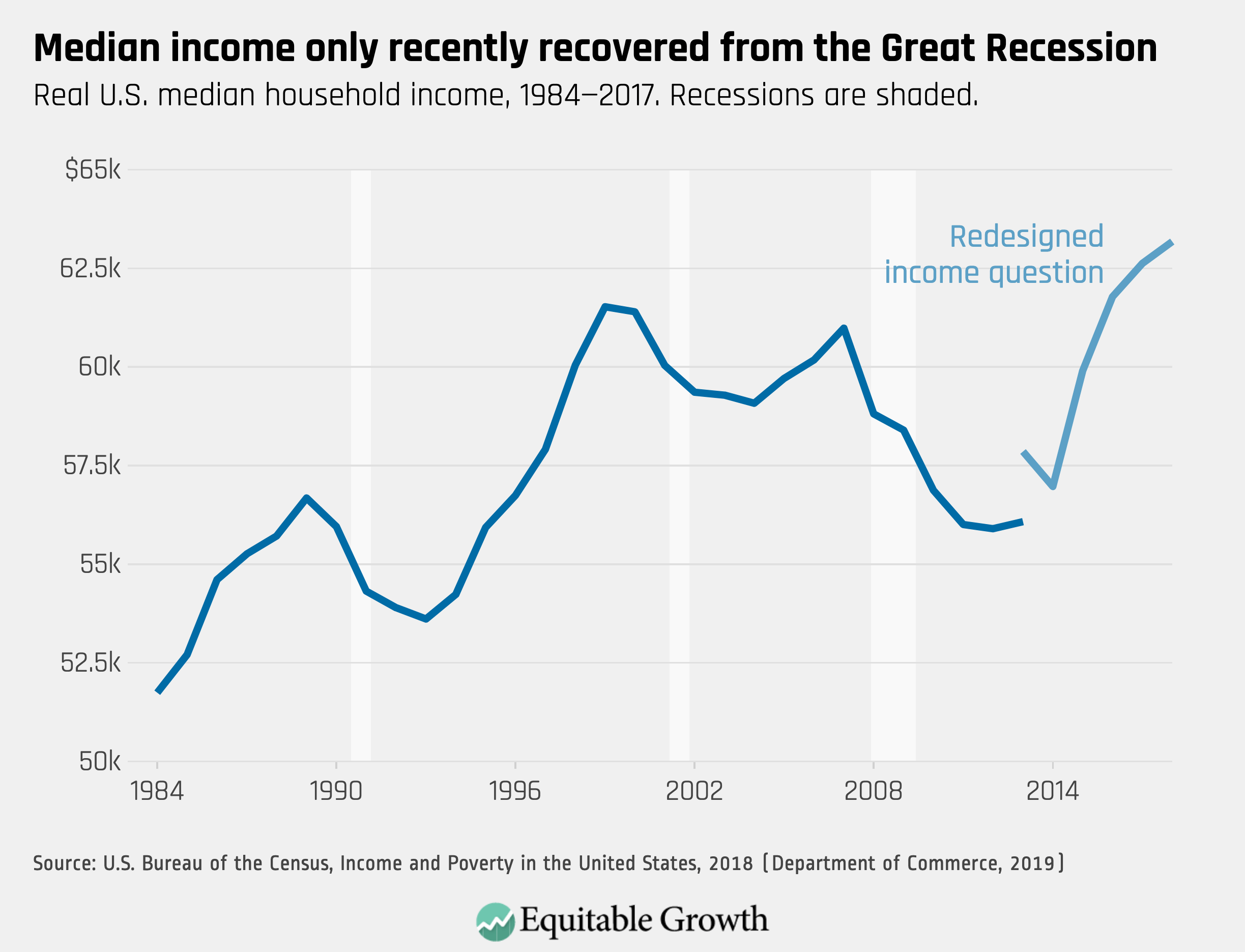

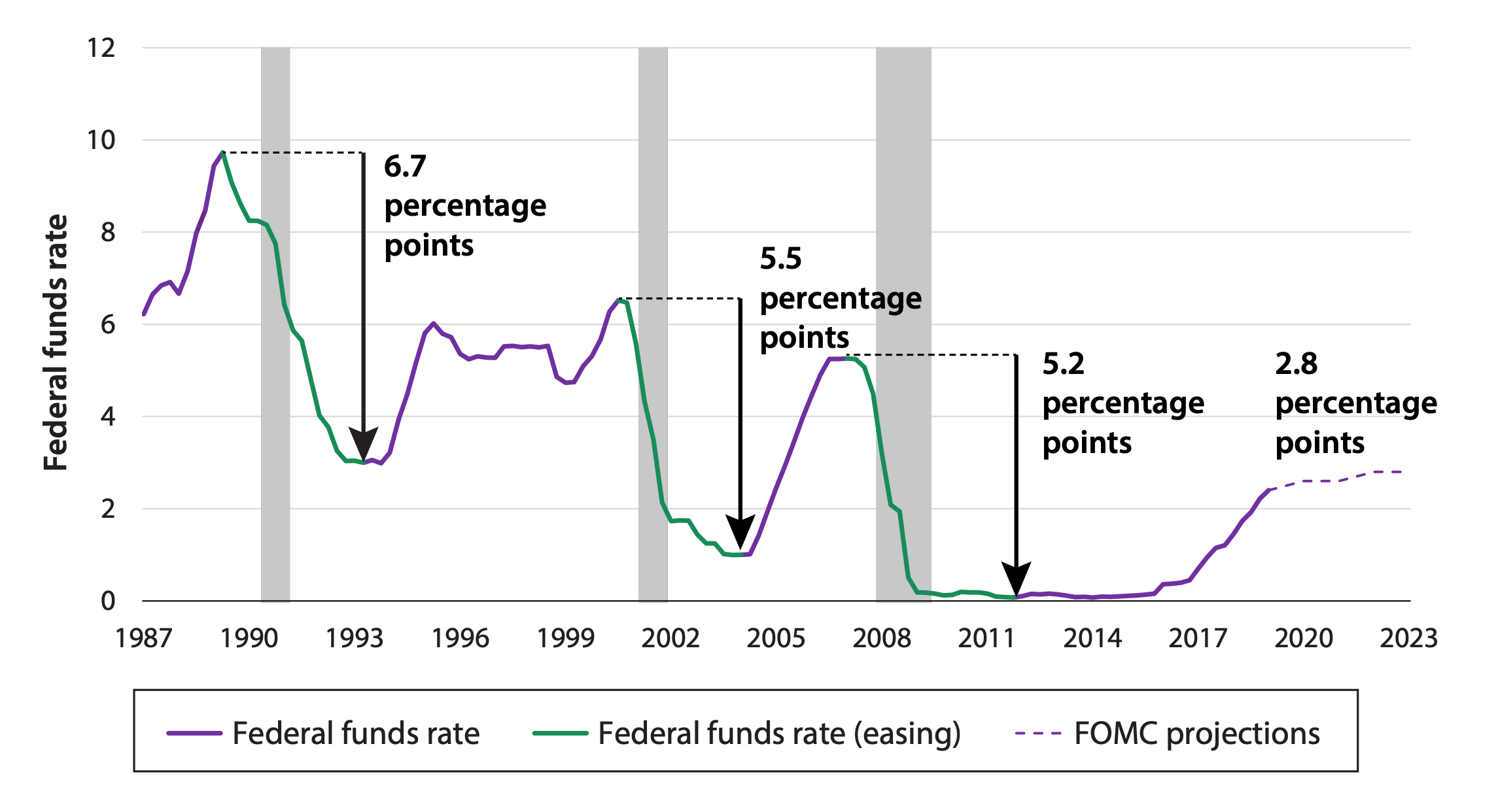

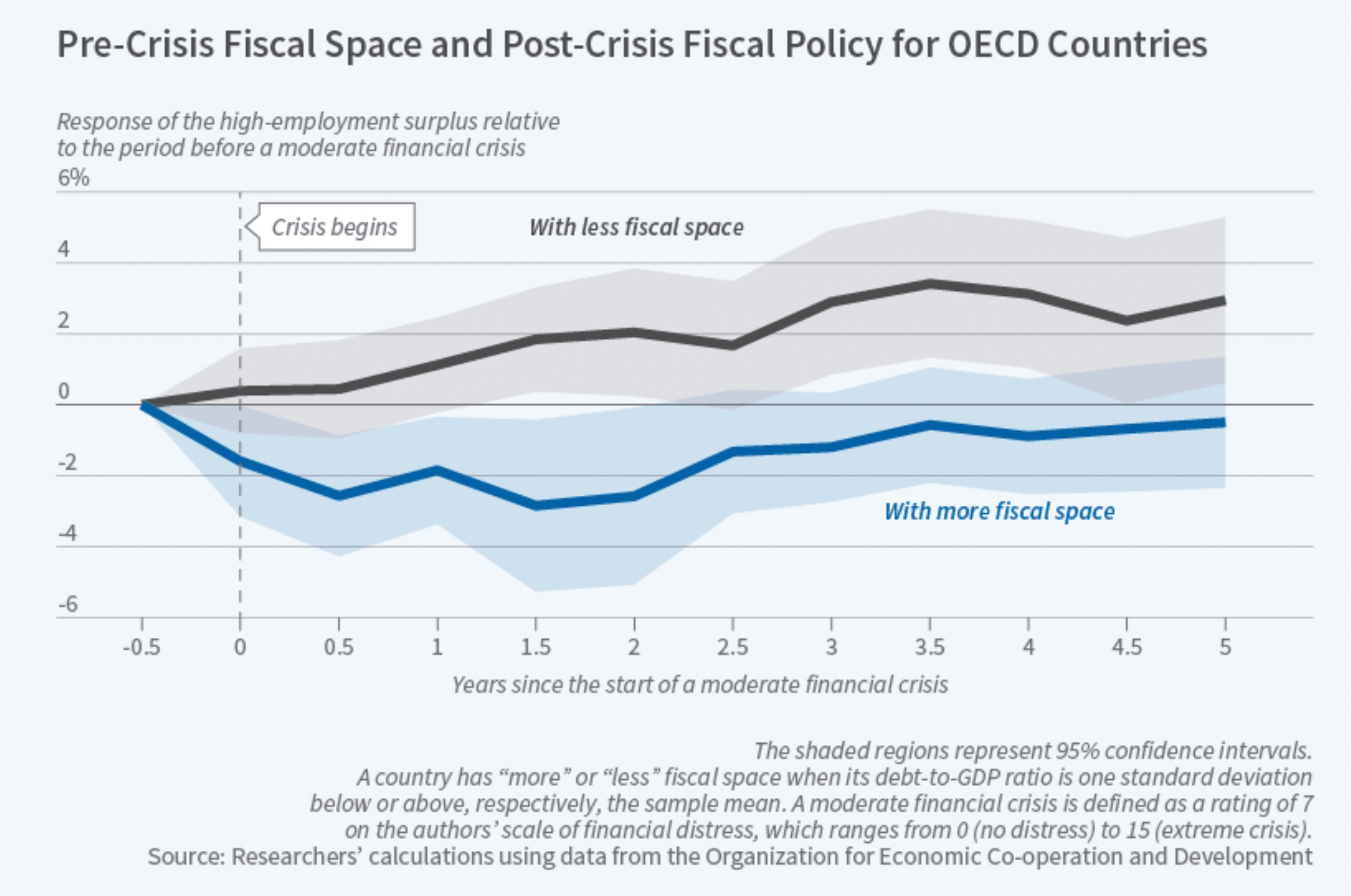

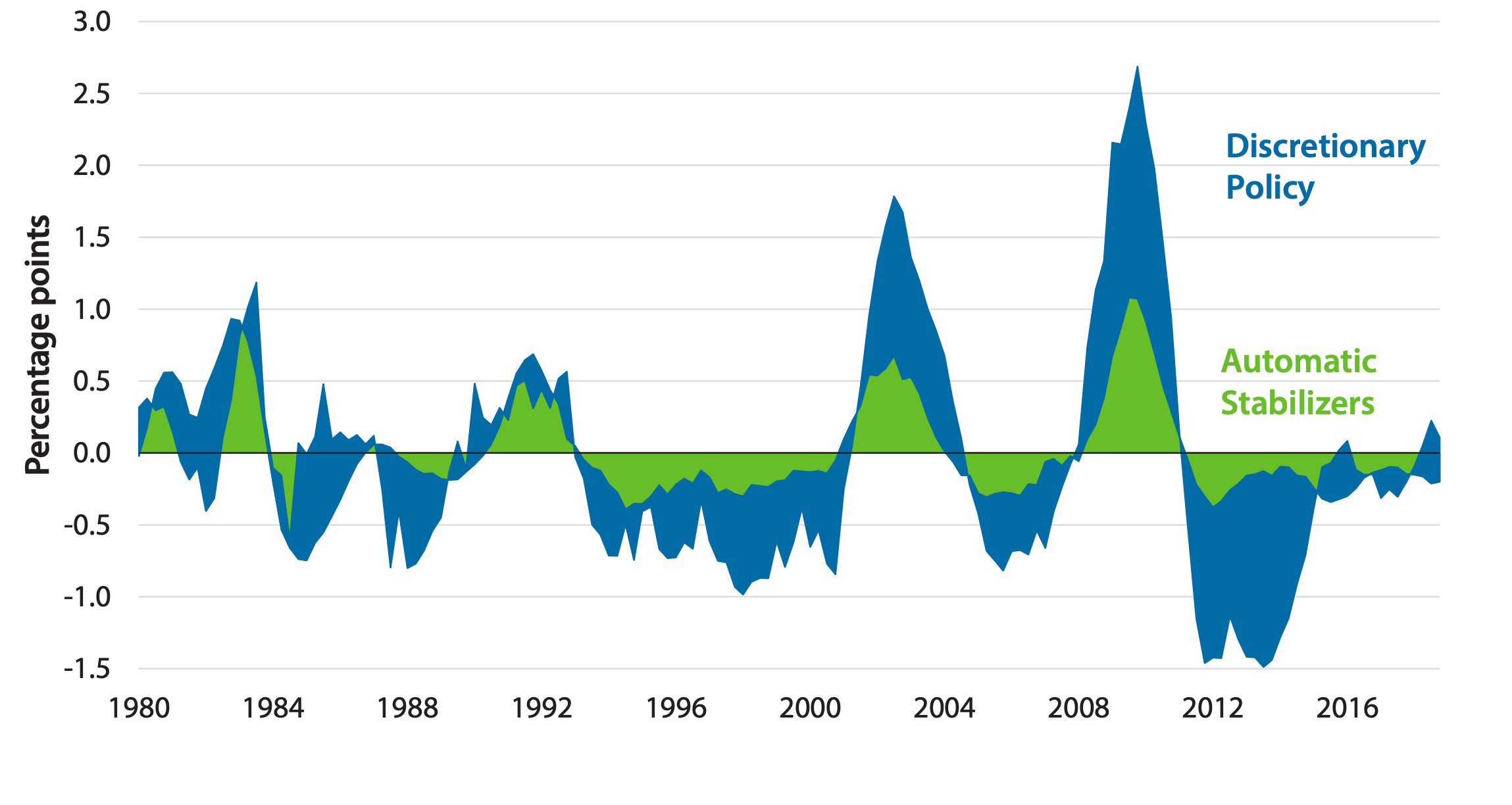

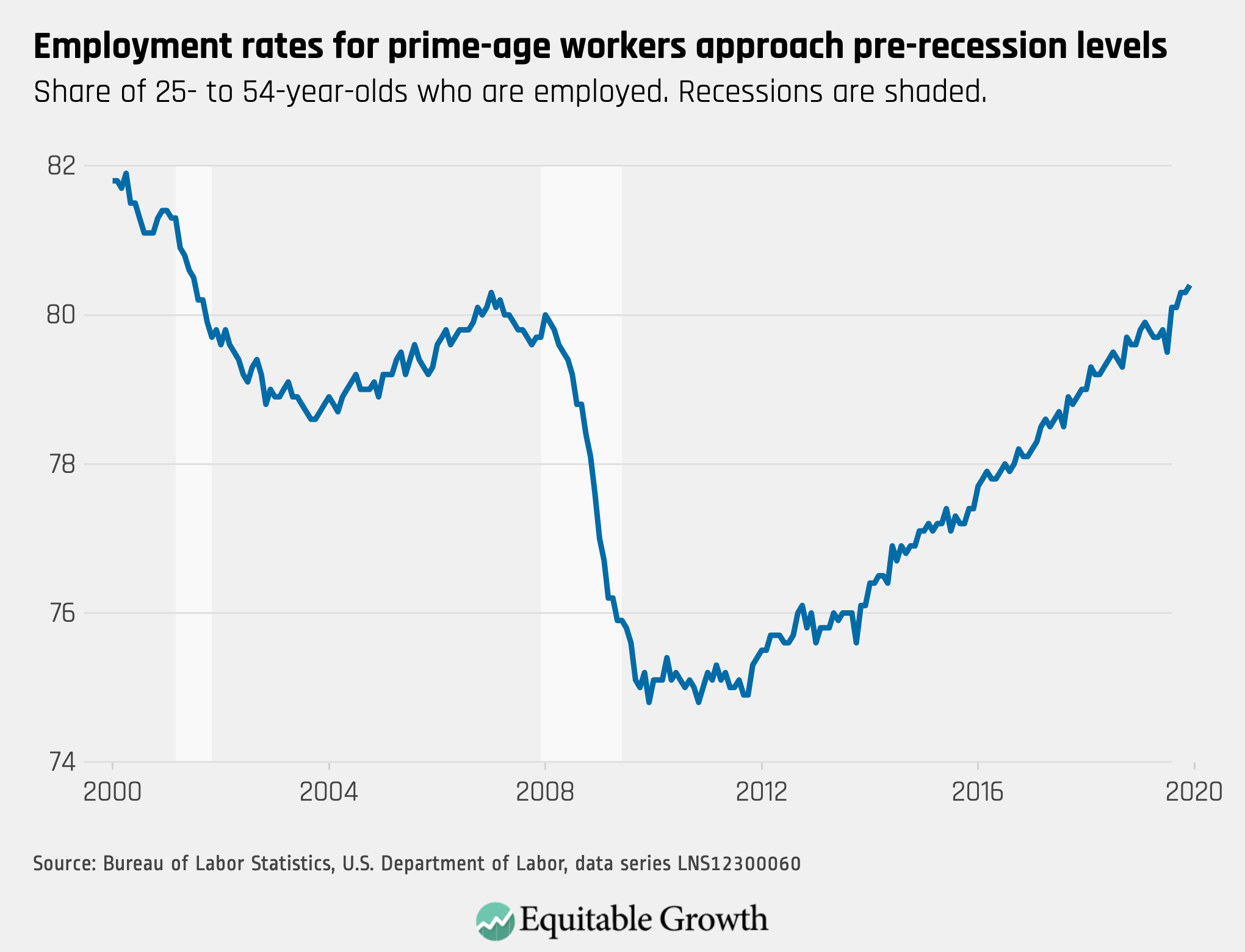

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics issued its monthly report on the U.S. labor market for December, showing high prime-age employment (above 80 percent) and high labor force participation, as well as continued short periods of time spent unemployed. The data also show wage growth flattening out after months of relatively steady increases. Raksha Kopparam and Austin Clemens put together five graphs highlighting these and other important trends in the monthly announcement.

Links from around the web

The United States is the only industrialized nation in the world that does not guarantee paid family leave to workers. But even though there is no federal paid family leave standard in place, eight states and the District of Columbia have passed laws to expand these kinds of benefits to workers, and President Trump recently signed into law a bill that guarantees such leave to around 2.1 million federal government workers—and private companies are taking notes, reports Jena McGregor for The Washington Post. McGregor writes about the various ways in which employees are using expanded access to paid leave, including to care for a new child, an ill family member, and an ailing pet. Here’s hoping a federal paid family leave guarantee for all workers is coming next.

Millionaires who aren’t against paying more in taxes? Yes, there is a group of ultra-wealthy individuals who think they should be doing more to fight income inequality. Led by Abigail Disney (yes, of those Disneys), the Patriotic Millionaires are a collection of rich Americans who are concerned about rising economic disparities— and, writes Sheelah Kolhatkar for The New Yorker, often speak out “in favor of policies traditionally considered to be antithetical to their economic interests.” Disney said she decided to start the group after realizing that the privileges she and her family experienced were cutting them off from the world and making it too easy for them to ignore the economic realities faced by most Americans. Kolhatkar tells the story of how Disney got to this point, and what she and her peers are doing about it.

As student loan debt rises and wages stagnate or drop, many younger Americans are now asking themselves if the costs of getting a university degree are still worth it. While some studies show that college graduates do earn more than their peers without a degree, a new study shows that these higher earnings don’t necessarily translate into higher prosperity and long-term economic security, reports Annie Lowrey for The Atlantic. “College still boosts graduates’ earnings, but it does little for their wealth,” she writes, going on to say that “if going to college is still important for young people’s earnings and employment, it is less of a clear economic boon that it was 30 years ago.”

California may take steps to be the first state that releases its own brand of generic prescription drugs in an effort to curb rising healthcare costs. The proposal is expected to be included in Gov. Gavin Newsom’s (D) new state budget, reports Melody Gutierrez for the Los Angeles Times, and allegedly would allow the state to contract with one or more generic drug companies to manufacture certain prescriptions under the state’s own label, which would be available to Californians at a lower cost. While we wait for more details on the plan, Gutierrez explains much of the motivation behind the proposal, as well as what critics and proponents are saying.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Equitable Growth’s Jobs Day Graphs: December 2019 Report Edition” by Raksha Kopparam and Austin Clemens.