The Washington Center for Equitable Growth was founded in 2013 to promote the use of research in policy and decision-making. Our strategy—to ensure that lawmakers and advocates are armed with rigorous evidence as they craft the policies that shape the U.S. economy and society—drives our work to this day. Equitable Growth’s growing network of scholars, grantees, and academics continues to inform and define our understanding of the origins and consequences of inequality and how to achieve strong, stable, and broad-based economic growth.

Our mission has never been so important as we deal with the ongoing effects of the coronavirus pandemic and resulting recession—and elevate our academic research and policy analysis to drive a more equitable economic recovery. That’s why we are heartened to see so many of the scholars with whom we’ve worked over the years either stepping into public service for the first time or returning to it, to bring evidence-backed policy into the executive branch.

Over the past few weeks, the Senate has worked to confirm a number of President Joe Biden’s appointees before adjourning for recess on March 29. One of the highest-profile appointments to President Biden’s cabinet is U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen. Secretary Yellen is the president’s chief economic advisor—an especially significant role given the continuing coronavirus recession and the importance of a speedier, more equitable recovery than happened after the Great Recession of 2007–2009, as well as the oversight that will be required to effectively execute the American Rescue Plan and future economic policy.

Equitable Growth was extremely fortunate to have Secretary Yellen as a member of our Steering Committee from 2018 through her nomination. During her tenure with us, she helped shape the organization’s research agenda by informing our annual request for proposals, and, along with other committee members, reviewed and approved our grantmaking for 3 years running—helping Equitable Growth zero in on a range of cutting-edge academic research projects that will help lawmakers advance policies to create more equitable economic growth. In addition, she advised on programming to increase diversity in the economics profession and ways to encourage economists to take more seriously research questions on race and structural racism.

Many other executive branch appointees are not Senate-confirmed but will be key to future economic policymaking. Perhaps most emblematic of the Biden-Harris administration’s incorporation of proponents of evidence-backed policy in government is our very own former President and CEO Heather Boushey, who is now a member of President Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers. Boushey co-founded Equitable Growth and spent years highlighting the value of connecting academia with policymaking to ensure that policies that were proven to be effective at combating inequality in the United States were put forward and prioritized by lawmakers. Last year, when the coronavirus pandemic began wreaking havoc on the U.S. economy and society, Boushey wrote and testified before Congress on policy proposals to both combat the recession and address structural barriers to economic equality, and brought these ideas with her to the administration.

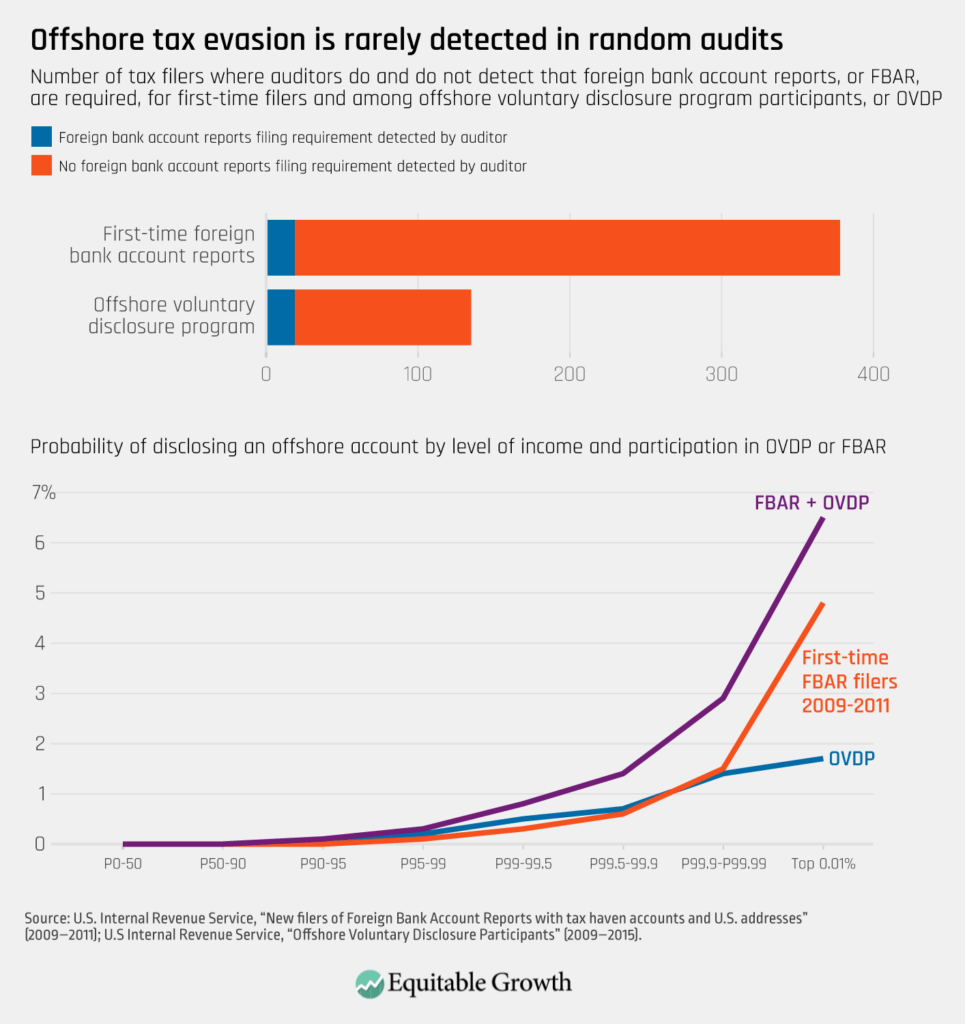

Similarly bringing evidence-backed economic policy expertise, specifically in the tax area, to the administration are Kim Clausing, who joins the Treasury Department as the deputy assistant secretary leading the Office of Tax Analysis, and David Kamin, the deputy director of the National Economic Council. Kamin, whose career and scholarship has focused on budget and tax policy, worked with Equitable Growth in the past, helping shape the organization’s position on taxing capital in ways that encourage widespread economic growth.

Clausing, who will be in charge of examining tax proposals to help decide which policies the Biden-Harris administration will pursue and how they will impact the overall economy, was involved in Equitable Growth’s early efforts to understand how the tax system could support a more equitable distribution of growth. She also received funding from Equitable Growth for her research on the corporate tax system, and has written for Equitable Growth on international trade and the coronavirus pandemic.

In her new role, Clausing will work closely with Lily Batchelder, who, upon confirmation by the Senate, will become the assistant secretary for tax policy within the Treasury Department. Batchelder is known for her research on inheritance and wealth transfer taxation, business tax reform, and social insurance.

Joining the Treasury Department in the area of macroeconomic policy is Neil Mehrotra, the department’s deputy assistant secretary of macroeconomic analysis. Mehrotra has been funded by and written for Equitable Growth on topics from secular stagnation and inequality to fiscal policy stabilization. His background in macroeconomics and previous position as an economist for the Federal Reserve Bank of New York further highlight his preparedness to analyze macroeconomic policy for the administration and guide decision-making to reduce overall inequality and bolster economic growth for all Americans.

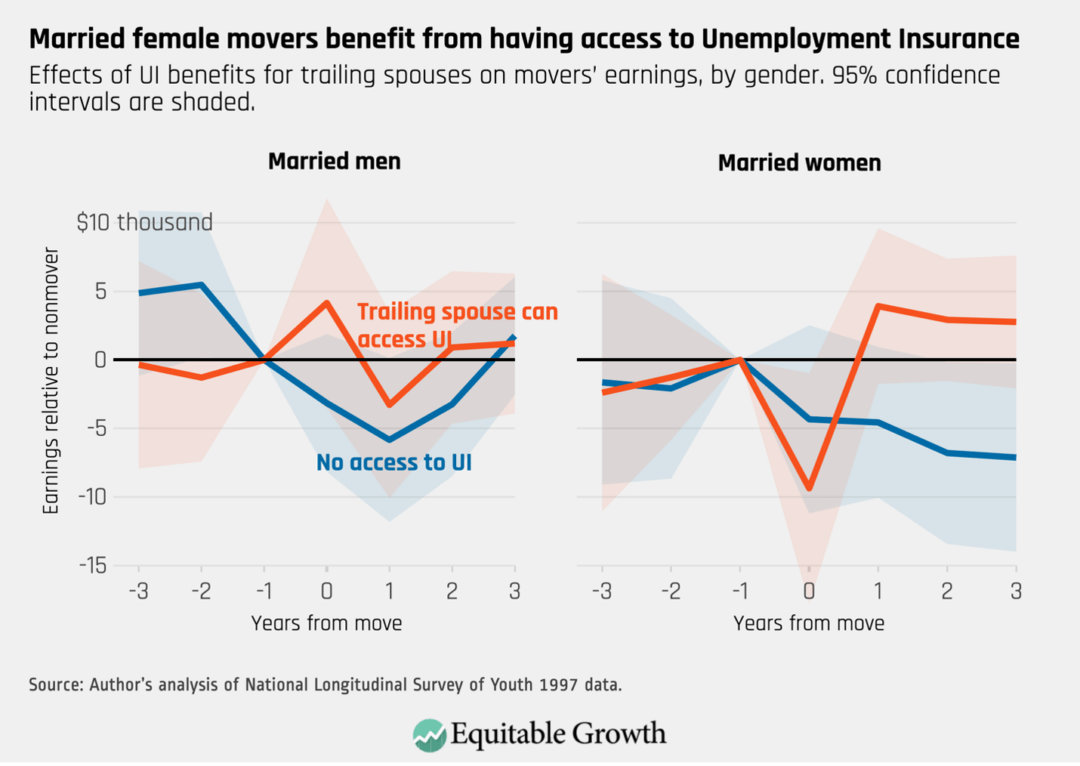

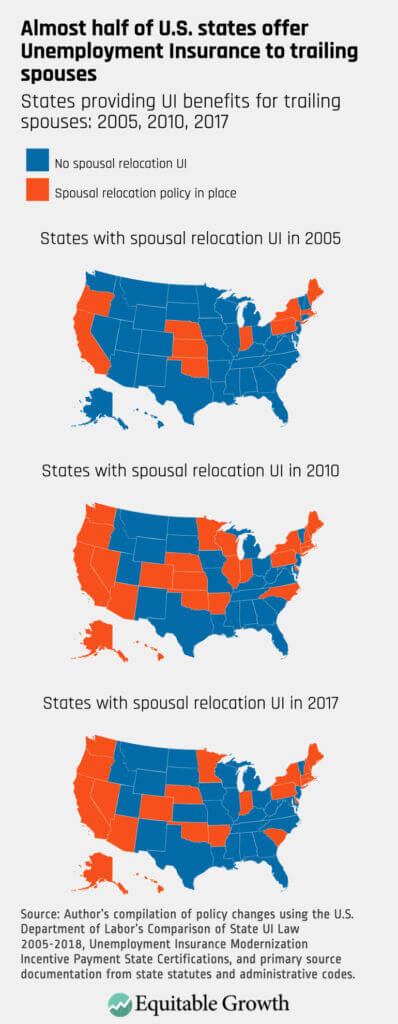

Moving to another area of the executive branch, Janelle Jones is the chief economist at the U.S. Department of Labor. Jones, who received an Equitable Growth grant in 2015 to study racial disparities in intergenerational wealth transfers, will now be the top economist advising Labor Secretary Marty Walsh, analyzing the labor market to guide policy decisions. Jones is best-known for her intersectional work on racial inequality, unemployment, and unions, and spent a decade studying the U.S. labor market before entering the Biden-Harris administration.

Also at the Department of Labor is former Equitable Growth grantee Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, who is now the department’s deputy assistant secretary for research and evaluation. In this role, Hertel-Fernandez will evaluate the effectiveness of Labor Department programs and project the impact of various policies on U.S. workers. He has written extensively for Equitable Growth on labor movements, labor law, and the relationship between unions and Unemployment Insurance, and received an Equitable Growth grant in 2017 to study worker preferences for labor organizing and representation across industries and occupations in the U.S. workforce, publishing his findings in 2019.

Leading economic policy for the White House Office of Management and Budget is Danny Yagan, who received Equitable Growth grants in 2014, 2015, and 2018, and presented at our 2018 grantee conference. His 2017 working paper, looking at the Great Recession’s effect on income inequality and employment in the years after the downturn, could have important implications as the coronavirus recession continues and President Biden works to tackle the resulting high unemployment. As OMB’s associate director for economic policy, Yagan is the top decision-maker on the economy in the budget office that sits within the Executive Office of the President, helping guide President Biden’s policy and spending priorities and reviewing federal regulations before they take effect.

All of these appointments, alongside many others, show how much emphasis the Biden-Harris administration is putting on research to guide its policymaking. This will have a direct impact on how those currently in power across the federal government consider and execute economic decisions, evaluate government programs and priorities, report data and statistics to the public, and more. Ideas that used to have currency primarily or only in academia about how to foster more equitable growth to power more sustained and broad-based economic well-being now have gained footholds in many corners of the new administration, in part because of Equitable Growth’s work over the past 7-plus years to fund and promote this research.

We congratulate the many new appointees to the Biden-Harris administration and look forward to continuing to advance evidence-backed ideas that ensure U.S. economic growth is strong, stable, and broad-based.