Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

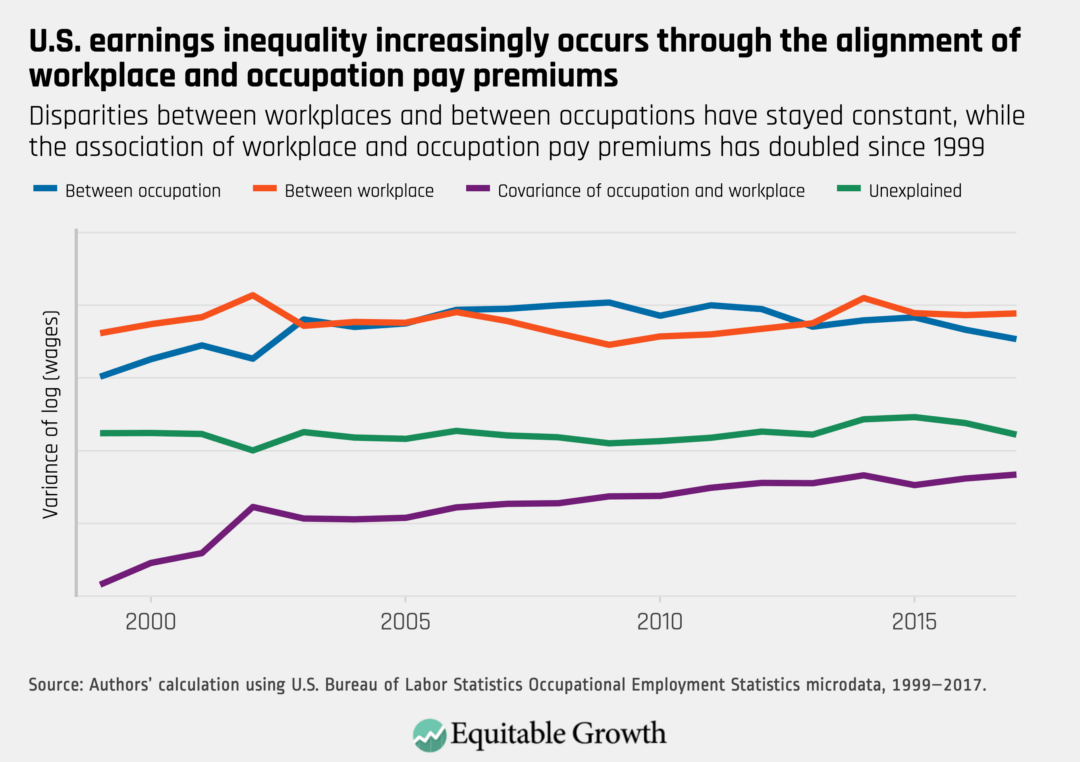

1. It used to be that there were high-wage occupations and high-wage firms, and that these were different and, to a large extent, countervailing sources of income inequality. But over the past generation this has ceased to be the case to a remarkable degree. How much of this is deunionization? How much of this is tech winner-take-all? And why has modern tech been so friendly to winner—or, rather, winning-team—take all? These are still profound mysteries to me. Read Nathan Wilmers and Clem Aeppli, “Consolidated Advantage: New Organizational Dynamics of Wage Inequality,” in which they write: “The two main sources of inequality in the U.S. labor market—occupation and workplace—have increasingly consolidated. Workers benefiting from employment at a high-paying workplace are increasingly those who already benefit from membership in a high-paying occupation. Drawing on occupation-by-workplace data, we show that two-thirds of the rise in wage inequality since 1999 can be accounted for not by occupation or workplace inequality alone, but by their increased consolidation. This consolidation is not attributable to firm turnover or to how occupations have shifted across a fixed set of high-paying firms (as in outsourcing). Instead, consolidation has resulted from new bases of workplace pay premiums. Workplace premiums associated with teams of professionals have increased, while premiums for previously high-paid blue-collar workers have been cut. Yet the largest source of consolidation is bifurcation in the social sector, whereby some previously low-paying but high-professional share workplaces, such as hospitals and schools, have deskilled their jobs, while others have raised pay. Broadly, the results demonstrate an understudied way that organizations affect wage inequality: not by directly increasing variability in workplace or occupation premiums, but by consolidating these two sources of inequality.”

2. This is a very nice survey indeed of the long-standing childcare-affordability problem in the United States. Read Taryn Morrissey, “Addressing the need for affordable, high-quality early childhood care and education for all in the United States,” in which she writes: “In 2017–2018, most children in the United States under 6 years of age—68 percent of those in single-mother households and 57 percent in married-couple households—lived in homes in which all parents were employed. Most of these families require nonparental early care and education … 12.5 million of the 20.4 million children under the age of 5 living in the United States (61 percent) attended some type of regular childcare arrangement … Families with young children are spending more on childcare than they are on housing, food, or healthcare … I argue that greater policy attention to early childcare and education is warranted for three reasons: High-quality early care and education promotes children’s development and learning, and narrows socioeconomic and racial/ethnic inequalities. Reliable, affordable childcare promotes parental employment and family self-sufficiency. Early care and education is a necessary component of the economic infrastructure … A universal early care and education plan, particularly one with a sliding income scale to provide progressive benefits, may not pay for itself in the short term, but will very likely do so in the long term by boosting broad-based U.S. economic growth and stability while narrowing economic inequality.”

3. The Chicago Law-and-Economics rollback of antitrust enforcement was not the worst thing to happen to the United States over the past half century. But we now have enough evidence to be confident that it was definitely a bad thing for the health of the U.S. economy. Read Fiona Scott Morton, “Modern U.S. antitrust theory and evidence amid rising concerns of market power & its effects,” in which she writes: “The experiment of enforcing the antitrust laws a little bit less each year has run for 40 years, and scholars are now in a position to assess the evidence … The bulk of the research featured in our interactive database on these key topics in competition enforcement in the United States finds evidence of significant problems of underenforcement of antitrust law. The research that addresses economic theory qualifies or rejects assumptions long made by U.S. courts that have limited the scope of antitrust law. And the empirical work finds evidence of the exercise of undue market power in many dimensions, among them price, quality, innovation, and marketplace exclusion. Overall, the picture is one of a divergence between judicial opinions on the one hand, and the rigorous use of modern economics to advance consumer welfare on the other.”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

1. I did a podcast on an excellent new book by Mike Konczal, Freedom From the Market: America’s FIight to Liberate Itself from the Grip of the Invisible Hand. His book is an example of the very nice work currently being done at the Roosevelt Institute. Please listen to my podcast with Mike Konczal and Noah Smith.

2. I have long thought that running so much of the U.S. social insurance system through the U.S. Department of the Treasury, the IRS, and the tax code is a significant mistake. We started doing this with the Earned Income Tax Credit simply because the late Senator Russell Long was chair of the Senate Finance Committee. And we are still doing it. It will require a lot of work to make the new and expanded Child Tax Credit work the way it does in the dreams of its proponents. And I do not yet see any sign that anyone in the administration is taking ownership of making this work. Read Annie Lowrey, “Calculate how much you would get from the expanded child tax credit,” in which she writes: “I’ve talked to a bunch of folks who will get the monthly CTC cash allowances, and none had any idea the money is coming. It’s a really complicated policy change (“a monthly advance on a newly fully refundable tax credit” is, I mean, even my eyes start to cross) and I hope there’s a concerted effort to increase awareness and participation rates … This is a good calculator/explanation! One thing to note is that you won’t get the money unless you file taxes, so super important for parents to do that even if their incomes are so low they don’t have to.”

3. Very smart people seem to me to have the wrong intuitions with respect to how the U.S. labor market works, the numbers of jobs, and the role of training. Seeking to have giant tech companies in some sense “grow their own” is, I think, a distraction. Read Zeynep Tufekci, “How Google’s New Career Certificates Could Disrupt the College Degree,” in which he writes: “More training is fine but there’s decades of research that the (obvious) key problem in the U.S. job market is the scarcity of good, stable jobs across the education ladder.”