Testimony by Heather Boushey before the Joint Economic Committee on the Coronavirus Recession

Heather Boushey

Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Testimony before the Joint Economic Committee,

Hearing on “Reducing Uncertainty and Restoring Confidence During the Coronavirus Recession”

July 30, 2020

Thank you, Vice Chair Beyer and Chairman Lee, for inviting me to speak today. It’s an honor to be here.

My name is Heather Boushey, and I am president and CEO of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. We launched in November 2013 with the goal of advancing evidence-backed ideas and policies in pursuit of strong, stable, and broad-based economic growth. We do this through a unique institutional strategy: We fund academics to investigate whether and how economic inequality—in all its forms—affects economic growth and stability. We have an open and competitive academic grants program that now, in our seventh cycle, has given away about $6.5 million to more than 250 scholars nationwide.

What the research now shows is that there are many ways that inequality hurts both families and the long-term trajectory of our economy. These long-term trends are inimically tied up in the current coronavirus pandemic and resulting recession.

The most important economic uncertainty facing your constituents and our nation is: When will the administration and Congress address the public health crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic?

Addressing the administration’s failure to contain the coronavirus and COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, is the only way to fully restore confidence and put us on the path to economic recovery. The United States is experiencing the most uncontrolled and deadly outbreak of any high-income country in the world. Compared to the European Union, we now record 10 times as many daily coronavirus cases and COVID-19 deaths.

Until the virus is contained, however, there are key actions that can bolster economic confidence and rein in uncertainty. Specifically:

- Immediately renew the $600 Pandemic Unemployment Compensation payments

- Set economic assistance programs, such as Unemployment Insurance, to continue automatically until objective economic conditions improve

- Pass generous aid for states and localities, which have already shed 1.5 million jobs and are bearing the brunt of responding to the pandemic, on the order of the $900 billion in the HEROES Act

- Resist enacting corporate liability immunity and instead release workplace health standards that protect workers’ lives and give employers evidence-based guidance

- Enact other policies to stabilize demand and help those most affected by the crisis, including:

- Food assistance

- Rental assistance and the extension of the eviction moratorium

- Direct payments to a broad swathe of low- and moderate-income Americans

- Investments in communities of color hit so hard by the coronavirus

- Funding to ensure safe and secure elections in November

- Help for small businesses

- Premium pay to our essential workers

- Fixes to the long-term fragilities detailed below that have made us so susceptible to this shock

- Build the data tools to know how this crisis and recovery are affecting families up and down the income ladder by enacting GDP 2.0 measures

The HEROES Act, which was passed by the House more than 2 months ago, contains many of these priorities. The Senate should immediately consider passing this bill or a similar bill that includes a recently introduced bill from Sens. Schumer and Wyden to peg expanded unemployment benefits to the economic conditions in each state. This would allow aid to automatically adjust based on objective criteria. Vice Chair Beyer has authored a similar proposal.

The coronavirus pandemic abruptly ended of the longest economic recovery in U.S. history. But before we get to the current situation, we need to acknowledge that even in those good years, the gains from that economic growth weren’t shared. This created systemic fragilities that left us less economically resilient and set us up for the multiple failures we are now experiencing.

The Roots of this Failure

This immediate failure is the result of a series of decisions made by this administration. But it also is the result of decisions made over the past 50 years that have created underlying fragilities in our economy and society. These decisions have made our economy less effective in good times and less resilient to shocks.

Even as the topline economic markers signaled to policymakers that our economy was growing last year—indicators such as a historically low unemployment rate and annual Gross Domestic Product growth of around 2 percent—wages were not growing commensurate with a tight labor market or at a pace to close our country’s unconscionable longstanding racial income and wealth divides.

The fruits of our economic growth, in terms of both income and wealth, were diverging sharply.

The Federal Reserve Board’s new Distributional Financial Accounts and the latest research by University of California, Berkeley economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman document that income inequality remained historically high, and wealth inequality was outpacing it.

Inequality hurts economic growth and mobility. Growth has slowed since 1980, and average people no longer share in the growth we do have. The bottom 50 percent of the population has the same inflation-adjusted pretax income that they did in 1980, and lower absolute mobility means that people born in 1980 now have only a 50 percent chance of surpassing their parents’ income.

As I summarize in Unbound: How Inequality Constricts our Economy and What We Can Do About It, at Equitable Growth, in our now 7 years of looking at the best economic research, we see that inequality constricts growth by:

- Obstructing the supply of people and ideas into our economy and limiting opportunity for those not already at the top, which slows productivity growth over time

- Subverting the institutions that manage the market, making our political system ineffective and our labor markets dysfunctional

- Distorting demand through its effects on consumption and investment, which both drags down and destabilizes short- and long-term growth in economic output

As a country, we have put ideology over evidence. We have chosen tax cuts and deregulation over investments such as paid family leave, robust social insurance programs, and public institutions. We have put our faith in the idea that markets can do the work of governing.

Instead, we should put our economy—and society—on a path where growth is strong, stable, and broadly shared. To do that, we need to enact policies that constrain inequality at the top, not allowing it to spiral out of control, and giving the beneficiaries of that inequality the power to subvert our markets, politics, or economy. And we need to provide counterweights to concentrated economic power. As we consider the economy we had at the onset of the pandemic, we can see clearly how failures to ensure workers and families, especially Black, Latinx, and Native American workers and families, have access to the tools to be healthy and safe—policies such as paid sick time, access to affordable healthcare, and well-enforced workplace safety standards—made our nation less resilient to this shock.

There are six key factors that made the United States and the U.S. economy particularly susceptible to the coronavirus pandemic and COVID-19. Each of them have contributed to the current crisis. And if they are not corrected, the United States is likely to experience a slow and inequitable economic recovery.

- Too many people lack the basic protections that would have slowed the spread of the coronavirus

The gaps in our social insurance systems exacerbated the spread of the coronavirus. The United States is behind its peer nations in labor market regulations to protect workers and families, including on paid leave, stable schedules, and access to child care. Compounding the problem is the lack of health insurance and fear of high medical bills, both of which kept—and are still keeping—those who feel sick from seeing a doctor, placing a serious burden on these individuals as well as raising rates of transmission.

Research is already showing the significant economic and psychological toll this pandemic is taking on workers. These stresses are heightened for people of color and immigrants, who face institutional discrimination and are often forced by their already precarious economic straits to succumb to workplace abuses at the hands of their employers.

- Workers lack the power to share in the gains of the economic expansion that would have given them protections and security

Civic institutions—especially labor unions, which once served as voices for many wage-earning workers (though never representing all workers)—have suffered a long decline. Now, only 1 out of every 16 private-sector workers belongs to a union. On top of this, labor laws and policies have failed to reflect the growing role of the fissured workplace in our modern-day economy, where firms subcontract pieces of their work so they can avoid responsibility for workers and working conditions.

These two debilitating trends in our labor market mean that corporations that are ultimately in charge of labor practices and that make the largest profits are not liable for maintaining 21st century workplace standards. The coronavirus pandemic exposed the failure of these labor market inequalities and the need for workers to manage health crises and family care, as well as protect workers against layoffs and the loss of these key health and family benefits.

- Decades of stagnant wages and meager workplace benefits leave many families without enough savings to weather the coronavirus recession

At the onset of the coronavirus pandemic in the United States, millions of people across the country were one paycheck away from financial catastrophe, even after a decade of economic expansion and historically low unemployment. Case in point: Four in 10 adults in the United States said that if they had a $400 emergency expense, they would have to borrow, sell something, or would not be able to pay it.

As the coronavirus recession continues, more and more workers and their families are robbed of buying power, which will undermine one of the key drivers of economic growth—the stable incomes that drive consumer spending.

- Policymakers starve public goods of investments that would have enabled better protections from the coronavirus pandemic and ensuing recession

Decades of tax cuts, culminating in the sharply regressive Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, have fueled a long-term decline in federal revenue that has starved resources that can be used to fund critical public investments and basic governmental functions, including in public health. High concentrations of income and wealth hamstring our political system because the wealthy dictate the legislative agenda and shape news headlines.

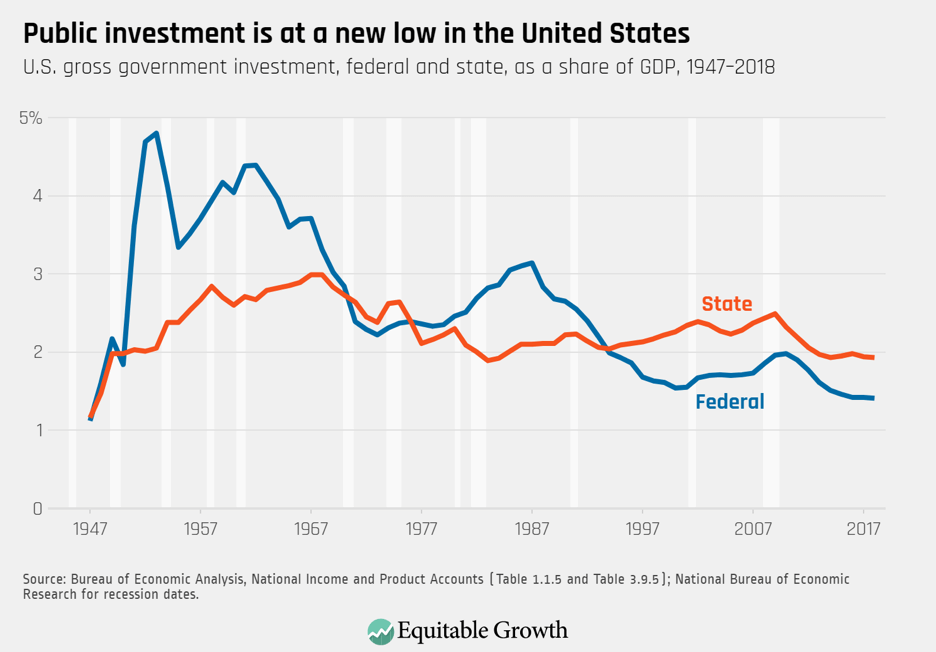

Yet these same wealthy elites don’t prioritize investments in public health infrastructure or other public goods. Early in this crisis, our neglected Unemployment Insurance system was unable to handle millions of Americans losing their jobs. Millions have waited weeks or months as decades-old computer systems struggled to process their claims. This dearth of investment is a systemic problem in the United States. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

- States and localities don’t have the resources to deal with a pandemic or a recession

State and local governments are experiencing sharp drops in their capacity to provide the services needed to cope with the coronavirus recession. Already, state and local governments have shed 1.5 million jobs. A continuing recession will induce further cuts to health and education and exacerbate the ongoing weaknesses. Austerity in state governments likewise disproportionately harms people of color, as public-sector jobs form the basis of a strong middle class for Black and Latinx workers.

- Business concentration across markets increases consumer and small business vulnerabilities just when those threats are most dire

Wealthy and powerful corporations use their status to maintain dominance in the marketplace. Large businesses and monopolies muscle competitors out of business, suppress wages, and hobble innovation. These companies are also precisely the ones that will thrive after the coronavirus pandemic passes. Strong cash reserves combined with political influence allow entrenched businesses to swoop in when asset prices are low and reshape rules of entire markets in the aftermath. The collapse of small businesses will disproportionately hurt people of color for whom business ownership is an especially important route to wealth creation and to closing the racial wealth gap.

The failure to prevent coronavirus infections and deaths and the ensuing recession

President Donald Trump’s focus is and always has been on the stock market rather than conceiving of and effectively implementing a comprehensive and fully thought-out federal plan to address the coronavirus pandemic and its economic effects. Case in point: Though the administration knew about the threat of the coronavirus in early January and took an early effort to limit the transmission into the United States by halting travel from China, where the coronavirus first emerged, it did not use that time to prepare sufficient stockpiles of medical and protective supplies.

Despite the months that have passed, the administration also has not set up a nationwide system to contact trace confirmed COVID-19 cases or given states the resources to do it themselves. And tests for the general population still can take a week or more to process and access too often varies by race.

Addressing the Immediate Economic Uncertainty

Unemployment Insurance

The largest economic uncertainty facing the United States is whether the Senate will renew the $600 increase in weekly unemployment benefits, known as Pandemic Unemployment Compensation, or PUC. The Senate majority has refused for months to act to renew this critical lifeline despite dire circumstances in the labor market.

In June, more than 11 percent of the workforce was unemployed, while the unemployment rate for Black workers was higher than 15 percent and more than 14 percent for Latinx workers. And conditions appear to have worsened in July as COVID-19 cases have resurged and states have been forced to re-enter various stages of lockdown. Unemployment claims numbers are rising once more, and a new survey from the U.S. Census Bureau shows that a staggering 6.7 million jobs have been lost since June.

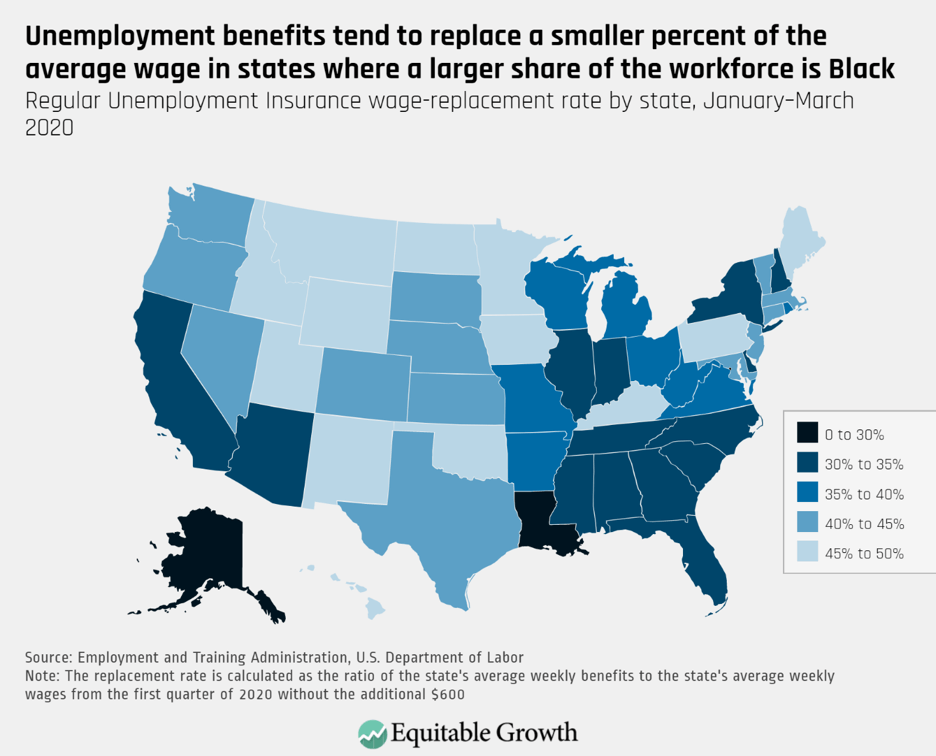

There is a racial component to the Senate’s refusal to renew the $600 PUC benefit. States with a higher share of Black workers tend to have less generous jobless benefits. For Black workers, an estimate shows, the average maximum weekly benefit is $40 short of that received by White workers. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

We risk a cascade of economic damage that could be uncontainable if Congress does not act immediately to extend the $600 unemployment benefit boost. Families need this benefit to sustain them. Their landlords need them to pay their rent, and their local small business owners desperately need them to keep ordering take-out and popping by for socially distanced shopping.

Like a virus out of control, high unemployment spreads economic pain throughout the entire community.

Unemployment benefits accounted for 14.6 percent of all wage and salary income in May. Failure to extend the $600 boost alone would contract GDP by a rate of 2.5 percent in the second half of this year, per an analysis by Harvard University’s Jason Furman. As a percentage, that is more than the economy grew in 2019.

Allowing the $600 boost to remain expired would devastate local economies.

Our communities rely on the temporarily unemployed being able to continue spending. States where unemployment benefits replace a greater percent of workers’ wages experienced the smallest drop in work hours in March—and, as of early June, had the strongest recovery.

There have been unfounded concerns that the $600 boost might be a meaningful disincentive to work during this crisis, perversely causing the very economic ailment is it meant to alleviate. This is not the case. The ongoing failure to be able to get back to business-as-usual due to the out-of-control pandemic, the absence of safe working conditions, a sharp drop in consumer spending, and lack of support for parents and caregivers are preventing millions from working, not Unemployment Insurance payments.

People are eager to get back to work when they have the opportunity, but there are not enough jobs in our labor market. The Job Openings and Labor Turnover survey shows that there were four unemployed people for every job opening in May. Lack of opportunities to work, not a lack of eagerness to work, are keeping unemployment elevated.

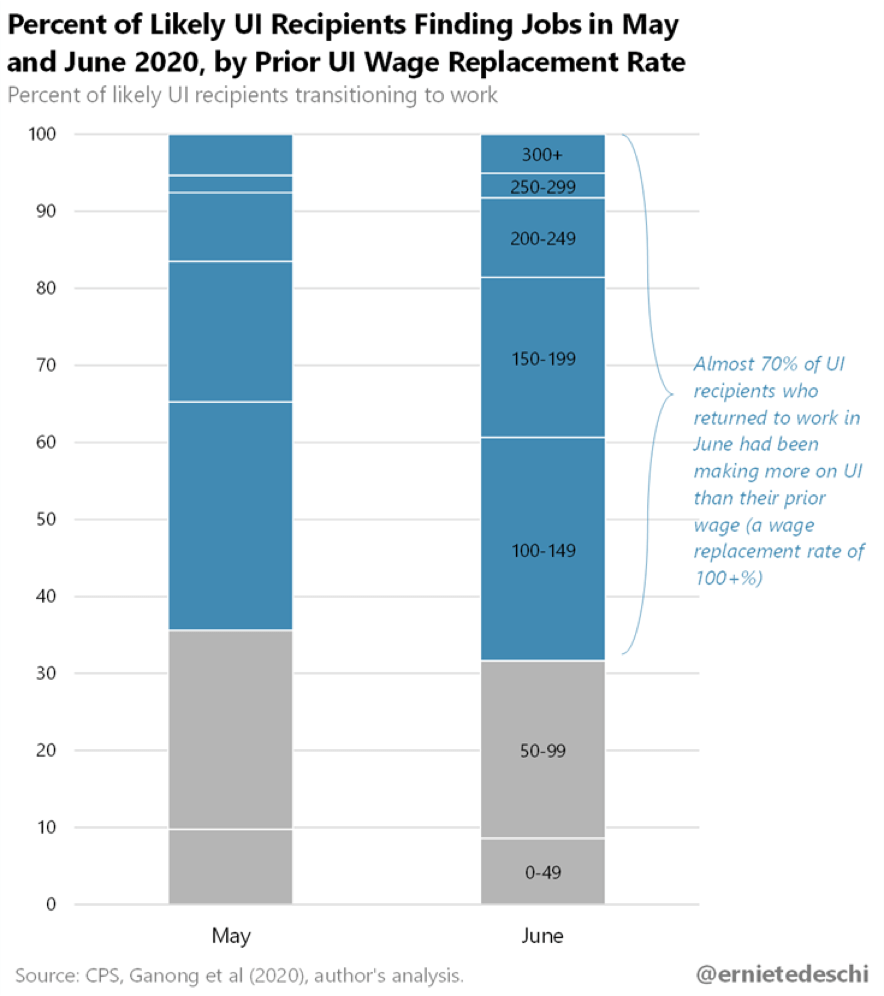

We can also see this in the population of people who returned to work in May and June after being laid off in April. Nearly 70 percent of those who returned to work in May and June did so despite the fact that they were making more from Unemployment Insurance than at their job, according to analysis by Ernie Tedeschi, an economist at Evercore ISI and former Treasury economist. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

In short, Americans want to work, and they know that a permanent job is more valuable than a temporary Unemployment Insurance check. This is one reason why employers are filling their scarce open positions faster than at any point since February 2012, as shown in the U.S. job vacancy yield.

Automatic Stabilizers

Nobody knows for sure how long the coronavirus recession will last or exactly how severe it will be. The uncertainty that would exist when confronting any recession is compounded by the uncertainty about the nature and consequences of the coronavirus itself, including the number of people who will die from COVID-19 now and in the future, the short- and long-term health impacts of the virus on those who recover, the pace at which treatments and vaccines will be developed, and the quality of the public health response.

Enhanced unemployment benefits should end when objective conditions show they are no longer needed. An unemployment-rate-based “trigger” that only turns off when a stable recovery is underway would allow this program to wind down automatically.

Sens. Schumer and Wyden have introduced a bill that would extend the $600 increase in weekly UI benefits beyond July 31, 2020 until a state’s 3-month average total unemployment rate falls below 11 percent. The benefit amount then reduces by $100 for every percentage point decrease in the state’s unemployment rate, until the rate falls below 6 percent. Vice Chair Beyer has sponsored a similar bill in the House. These bills follow the best evidence in research-driven policy design, inspired by research on automatic stabilizers from Equitable Growth and the Hamilton Project’s book Recession Ready.

State and Local Government Aid

The next priority, if Congress wants to create economic certainty, is to pass fiscal relief for states and localities with around $900 billion in aid in the HEROES Act.

States and localities are bearing the brunt of responding to this virus in light of federal inaction. They are losing tax revenue and, as a result, have shed 1.5 million jobs so far—even as their services are more necessary than ever. These job losses make up a significant portion of the overall 12 million jobs permanently lost since February.

With state and local general fund revenues in freefall due to needed increases in spending on healthcare and related spending amid plummeting tax revenue, these governments’ budgets are on the precipice. State budget shortfalls could total more than $550 billion over the next 3 years, nearly double what it was estimated states missed out on in the entire decade following the Great Recession more than a decade ago. Fiscal requirements that states balance their budgets are already forcing governors to propose cuts in spending that will harm already struggling communities. Local governments are, if anything, in an even more challenging economic situation.

During the previous recession, these budget cuts proved seriously harmful to the economy. Shrinking state and local government budgets during the Great Recession reduced Gross Domestic Product by more than three times the size of the cuts themselves, according to estimates.

Other Crucial Policies

Other policy priorities include food assistance, rental assistance and extension of the eviction moratorium, investments in communities of color hit hard by the virus, funding to ensure safe and secure elections in November, help for small businesses, and premium pay to our essential workers. And I urge you not to support enhanced liability protections for big corporations facing lawsuits if they put their workers at risk. Federal policymakers need to provide evidence-based guidance so firms open safely, not shift risks onto workers.

Finally, Congress should also implement new data tools to measure how the recession and recovery will affect people differently up and down the income and wealth ladders. The GDP 2.0 measure Equitable Growth has proposed, and which I have previously discussed before this Committee, will tell us whether families are recovering from the crisis and which need more help. We can lay the groundwork now to make sure we understand who benefits from a future recovery and what other action is needed.

We can see clearly that markets cannot perform the work of government. Americans need public institutions that can protect them from threats to their lives and livelihoods, and provide leadership in times of crisis. Our economy and society have a long way to go to get back to full health. We have even further to go to implement fixes for our long-running systemic fragilities. I thank you for the chance to submit this testimony on how you can do just that.