Latest jobs report for June reveals pre-existing inequality in U.S. labor market worsening amid coronavirus recession

The latest jobs numbers released by the federal government today indicate the brunt of the job losses due to the coronavirus recession continue to fall heaviest on Black and Latinx workers, even though the month-on-month changes between May 2020 and June 2020 were better overall. Over those 2 months, the U.S. economy gained 4.8 million nonfarm payroll jobs, the share of the employed prime-aged population increased from 71.4 percent to 73.5 percent, and the jobless rate fell from 13.3 percent to 11.1 percent.

This latest monthly Employment Situation Summary—also known as the Jobs Report—from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that the U.S. unemployment rate is now below its April peak but remains well above the Great Recession high of 10 percent. What’s more, the share of unemployed workers who report having permanently lost their jobs increased for the second month in a row, jumping from 14 percent in May to 20.9 percent in June.

June’s Jobs Report also suggests that the improvements in the labor market have been uneven, and that Black and Latinx workers, in addition to women workers and low-wage workers generally, continue to be disproportionately affected by the coronavirus recession.

Even though the unemployment rate has been greater for women than for men since April—a relatively novel phenomenon since experience from previous recessions shows that men tend to lose more jobs early on in downturns—the gap between the two rates narrowed last month. Whereas men’s unemployment rate dropped from 12.2 percent in May to 10.6 percent in June, women’s declined from 14.5 percent to 11.7 percent.

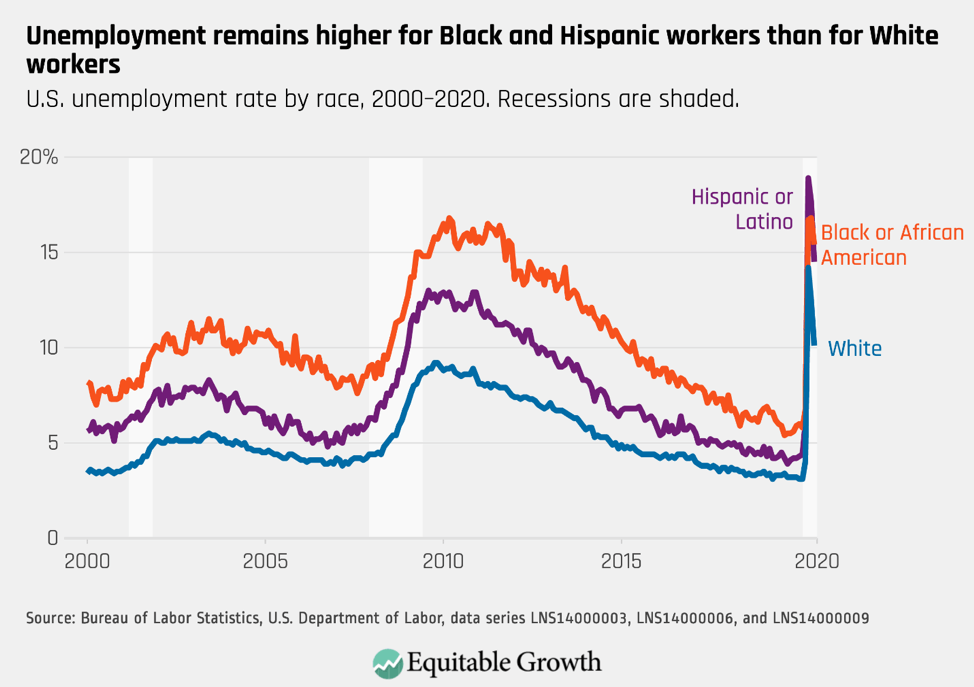

But the gap between Black and White unemployment widened. The jobless rate of White workers fell from 12.4 percent in May to 10.1 percent in June, but Black workers’ unemployment rate only fell from 16.8 percent to 15.4 percent. And despite experiencing the largest month-to-month drop, going from 17.6 percent to 14.5 percent, Latinx worker’s jobless rate is 4.4 percentage points above that of their White counterparts.

Some of these data points should be taken with caution, however, since the Jobs Report sampling size makes small changes in Black workers’ labor market indicators difficult to interpret. Indeed, the disparate impacts of the coronavirus recession by race and ethnicity highlight the need for oversampling of minorities in the workforce in surveys.

Yet analyses using alternative sources of data also provide insight into these racial and ethnic disparities. Industries with the lowest average wages saw the biggest increases in employment this month, but research using data from payroll-services provider Automated Data Processing, Inc., finds that losses have been much more severe for low-wage jobs—positions in which Black and Latinx workers are overrepresented. The ADP data show that only a relatively small share of that difference can be attributed to workers’ age, the size of the business in which they were employed, or the industry in which they worked.

The disparities between races also reflect that, in other ways, the coronavirus recession is not unlike the previous ones. Researchers found that in Black workers were more likely to exit work in April and less likely than their White and Latinx counterparts to be rehired in May, as some businesses reopened. This trend is consistent with existing research, which shows that at least since the 1980s, Black workers have been more likely to be displaced from their jobs. This disparity, moreover, has become larger since the 1990s. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

There are similar findings in the case of women workers, showing that women’s overrepresentation in industries such as leisure and hospitality—a sector that, even after recovering 2.1 million jobs this month, has seen a massive 29 percent decline in employment since February—cannot fully explain why women are continuing to lose their jobs at a higher rate than men, since they are also experiencing more severe unemployment within industries. That women and women of color in particular have been hardest hit by this recession is likely driven by their overrepresentation in lower-wage and insecure occupations within sectors.

This trend also reflects feminist economists’ insight that the current health crisis and the disruption to education caused by the coronavirus pandemic have fallen more heavily on women. They continue to do the lion’s share of the unpaid work of caring for their families.

The relatively rosy jobs report this month masks other disconcerting trends. With almost 15 million nonfarm payroll jobs lost since February, more than four unemployed workers for every job opening, and some states backtracking on the reopening of businesses due to a surge in new coronavirus infections, the prospect of a fast economic recovery is slim. Moreover, important government financial support that helped keep workers whole and the economy out of freefall since March is set to expire in the coming months.

At the end of July, the extra $600 a week in emergency Unemployment Insurance will expire, including for so-called gig workers, who, for the first time, were able to tap unemployment benefits. And companies that borrowed funds beginning in April under the federal Paycheck Protection Program to keep their employees on payrolls will no longer have to do so beginning 8 weeks later, which means many of those employees could be furloughed or let go over the next 2 months.

In the next coronavirus recession relief package now under debate on Capitol Hill, Congress should increase access to the additional $600 weekly Unemployment Insurance benefits beyond the end of July, and only scale back unemployment benefits as the jobless rate declines by enacting automatic stabilizers. Policymakers also should provide financial support for state and local governments so they can avoid layoffs of critical public-sector employees amid the pandemic, and increase federal support for social infrastructure such as paid leave and health insurance systems. Doing so would bring some security to workers and their families, and make an eventual recovery both quicker and more equitable.