Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

1. If the distribution of U.S. income and wealth is not moving much, and if one is (for reasons that are largely tactical-political) willing to submerge questions about the current state of the distribution of income and wealth, then there is some sense in taking measures of national income as a summary statistic of the state of the U.S. economy. If not, not. For a generation and a half it has been clear that neither of those conditions holds anymore, if they ever really held at all. And yet we are still using national income as our summary statistic—when we are not using the stock market, that is. Read Austin Clemens, “Measuring economic outcomes for all U.S. workers and their families will hold policymakers accountable for creating broad-based growth,” in which he writes: “U.S. GDP is completely inadequate for understanding our modern economy or the well-being of U.S. workers and their families. It cannot tell economists or policymakers anything about the informal work sector, inequality in the economy, sustainability, and myriad other issues that are essential for policymaking in the 21st century. The problems with the GDP measure are emblematic of the work by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth to improve economic measurements. We know from research that changes in GDP have a huge impact on the tenor of economic narratives in the United States. But we also know that GDP is increasingly disconnected from the experience of most U.S. workers and their families, most of whom generally see increases in their own incomes that are well below headline GDP figures.”

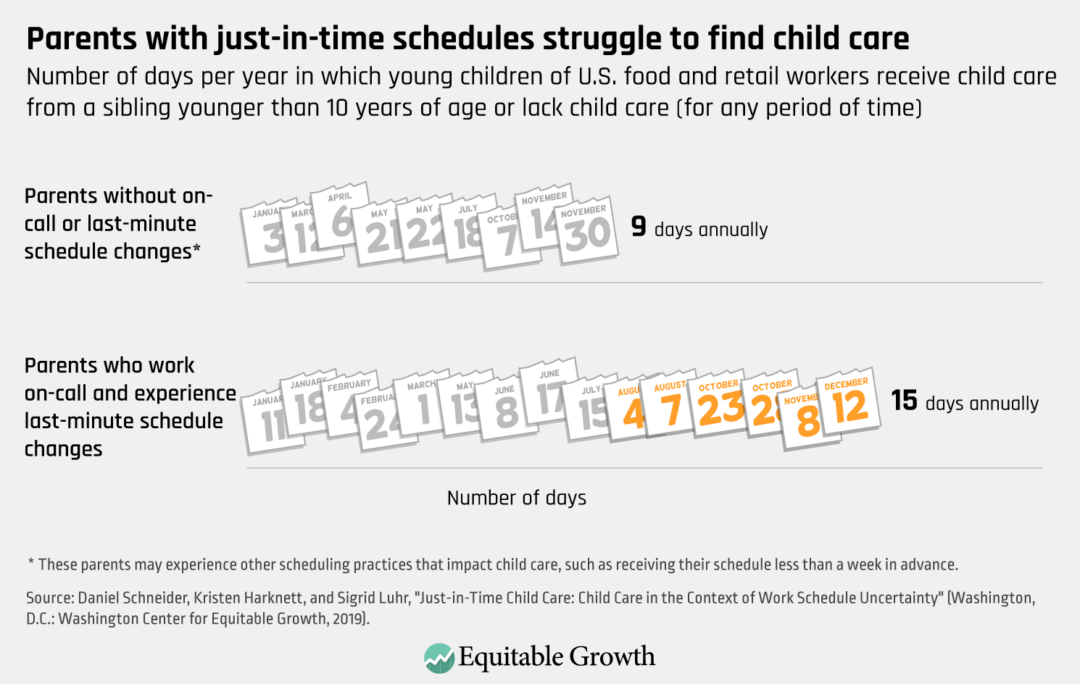

2. I find myself returning to this often: U.S. society and its family organization setups did make some (although not a great deal of) sense with respect to economic efficiency and the societal work of child care back in the large-family era before the demographic transition, but that is now a century ago. And today there remain mammoth failures of readjustment, many of them linked to the survival of the expectation that the past denial of female opportunity creates a large captive care-work labor force that can be paid low salaries. Read Sam Abbott,” The child care economy,” in which he writes: “Investments in early care and education can fuel U.S. economic growth immediately and over the long term. Fast facts: Insufficient child care options can prevent parents who wish to work from doing so, with mothers often bearing the brunt of this challenge. Among parents who wish to work, child-rearing tends to interfere more with women’s labor supply and employment outcomes than with men’s. This leaves potential economic growth unrealized, as women’s labor force participation is significantly associated with Gross Domestic Product growth. High-quality early care and education provides critical socialization and learning opportunities when the brain is developing rapidly and is particularly responsive to the outside environment. Young children in pre-Kindergarten programs experience positive developmental outcomes and are better prepared for school, scoring higher than their peers on standardized measures of reading, spelling, math, and problem-solving skills. Adequate funding is necessary for human capital development. Fully funding the subsidy programs and devoting resources for state-level agencies to assist providers in qualifying for subsidies are two ways in which greater public investment could increase child care availability and quality. Supporting child care workers is crucial for promoting quality care and human capital development. Using public funds to support higher compensation would help stabilize the child care workforce, ensuring that these workers can afford to stay in their jobs. Investing in the nation’s children is one of the safest bets policymakers can make. Research on early care and education programs finds that $1 in spending generates $8.60 in economic activity.”

3. Another one of my favorite moments from the Equitable Growth 2021 conference. Watch Michelle Holder and Lisa Cook, “Michele Holder on child care and the economy.”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

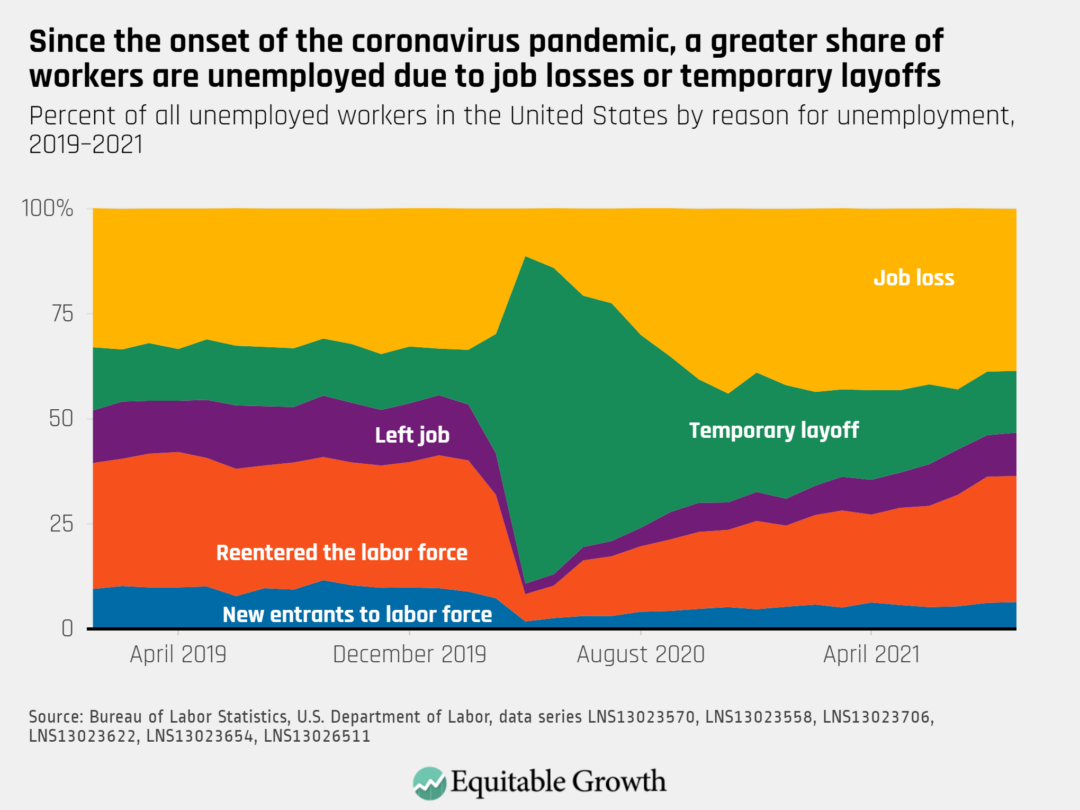

1. Dan Alpert is right. The cutting-off of income support to the unemployed in the United States after the coronavirus recession is a huge, huge shock. Yet this past Friday’s employment numbers show not a ripple. This powerfully reinforces the view that the end of income support is having no effect on U.S. labor supply whatsoever. Thus everybody who has been talking about the adverse labor-supply effects of income support really needs to take a hard look at their thought processes. Read Dan Alpert’s twitter response to the those numbers, in which he notes: “Second only to the lockdowns in spring of 2020, the biggest pandemic-era shock to the U.S. employment situation was the elimination—by law, not economics—of nearly 10 million workers from the unemployment benefit rolls in September. Will that register yet in payrolls? Stay tuned.”

2. In the world in which there are powerful psychological and institutional reasons why nominal wage and price levels in many, many sectors and for many, many occupations are sticky downward, structural adjustment via the market requires some inflation. And the more structural adjustment there is to be done in a shorter time, the more inflation is a desirable addition to rather than a subtraction from the supply-side potential of the economy. And yet there are a remarkably large number of people who do not factor this into their thinking. They continue to hold, no matter what the underlying realities of the fundamental economic situation, the inflation target that Alan Greenspan kicked out of the air in the 1990s as if it were a sacred totem. Read Andrew Elrod, “The Specter of Inflation,” in which he writes: “What are we to make of the jump? Thirteen years ago the bulge in prices was concentrated in petroleum products and food; today the spike is driven by used cars, airfare, and restaurants—sectors acutely impacted by the pandemic. But unlike 2008, there is little reason to suspect today’s rising prices are evidence of an overactive economy. The U-6 rate of total unemployment, which includes those working part-time involuntarily and those who have quit looking for work, remains 9.2 percent. Total capacity utilization, meanwhile, remains sharply depressed at 76 percent. … The history of inflation politics has a very different lesson. … Inflation is not always a problem of excess demand; it can also be caused by mismatch between existing demand and existing supply—a problem of shifting supply to changing demands. (Arguably this is what we are seeing now.) Moreover, reducing the level of spending in the economy can prevent us from achieving other, higher goals. … Both Harry Truman and Franklin Roosevelt confronted inflation without hiking rates and tightening budgets, and there is no reason governments can’t manage their economies similarly today. Inflation, in short, does not have to be a totalizing problem, and we certainly have better prescriptions for dealing with it than those on offer today. The far greater threat, history shows, is inflation fearmongering.”

3. Yes, it would be nice to have cheap reliable zero-carbon fission power. Yes, France got there. Yes, it would be even nicer to have even cheaper and more reliable fission power. Yes, it would be nicer still to have cheap reliable fusion power. But it really looks like, for the next generation at least, the low-hanging economic fruit is all in solar power. It would be silly to make a difficult-to-attain second-best the enemy of a first best that is already at hand. Read Noah Smith, “Nuclear vs. Solar,” in which he writes: “One has promise for the future. The other is changing our world right now. … I would love to see technological breakthroughs that solve fission power’s basic problems, and fusion, if it works would be even more exciting. … France’s experience powering itself largely with nuclear reactors (thanks to massive government financing and coordination) shows that we could have done so safely and efficiently—and reduced our carbon emissions enormously in the process—had we chosen to do so. Furthermore, scrapping existing nuclear power plants, like the one at Diablo Canyon, is crazy, and will increase carbon emissions for no good reason. … ‘Clean firm’ power is key to rapidly decarbonizing the grid, and nuclear power is one of the ways we get that. In sum, I am pro-nuclear. But I also feel that many of my techno-optimist friends, in their focus on the promise of nuclear, are giving short shrift to the even greater technological revolution happening right under their noses—the unbelievable progress in both solar power and battery storage. If you are a true techno-optimist, you should definitely be excited by this! It’s not the kind of thing that happens once in a generation—it’s the kind of thing that has never happened before.”