Brad DeLong: Worthy reads on equitable growth, October 19-25, 2021

Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

1. Highlighting this from a year and a half ago from Equitable Growth’s new president & CEO. Read Michelle Holder, “The “Double Gap” and the Bottom Line: African American Women’s Wage Gap and Corporate Profits,” in which she wrote: “Though African American women have historically had the highest labor force participation rate among major female demographic groups in the United States, they face both the gender wage gap and the racial wage gap—a reinforcing confluence that I term the ‘double gap’… [showing] that both the share of women in the labor force and the crowding of women into low-wage jobs are negatively correlated with the labor income share.”

2. Check out Equitable Growth’s new “A Visual Economy,” which features “visuals on a particular topic related to economic inequality and equitable growth … [and] offers a way to sort through thousands of figures produced since the beginning of 2019. The six ‘Featured Visualizations’ … showcase some of our most recent work and older classics. Filter and download our visuals using 31 different economics topics as well as by our signature ‘Jobs Day’ and ‘JOLTS Day’ features.”

3. Read Liz Hipple and Alix Gould-Werth, “Weak income support infrastructure harms U.S. workers and their families and constrains economic growth,” in which they write: “People in the United States access income support from a wide range of programs … [yet] many … who need this support are blocked from accessing it. During the COVID-19 crisis, the existing income support infrastructure has been wholly insufficient. … While … pandemic-specific income supports … blunted some of the worst pain … they also failed to deliver for all … due to sustained underinvestment in these key income support programs over the past half-century.”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

1. The very sharp Ryan Avent hammering home the point that the failure of equitable growth to happen in the 2010s was not due to any structural or supply-side failures of human and other resources to exist or be mobilized, but just to prolonged, sustained weakness in aggregate demand. Read his “Revenge of the robots,” in which he writes: “If the Fed doesn’t overreact to inflation and other events don’t blow up the recovery, then this labor market has some room to run. Workers at the bottom of the distribution are getting better money, which should support continued demand growth, which should keep the economy humming, which should prevent the emergence of lots of new slack—for now. … In many industries we already have in place business models that use less labor more productively, but which have not yet become dominant because broader conditions haven’t been sufficiently encouraging. … The technological capacity to automate the work of large swathes of the labor force has been building over time but hasn’t materially affected labor markets yet because there’s been no incentive to make use of it. … Alternatively, industry shake-ups and the occasional adoption of labor-saving methods and technologies begin to undercut the earning power that workers enjoy, and after a glorious few years wage growth decelerates. As it does, and the share of purchasing power held by those with a high propensity to spend declines, the old macroeconomic malaise sets in again. … The current labor-market boom demonstrates that weak demand was the thing that made the 2010s so crummy.”

2. Lots of us have been seeing a silver lining in our belief that China’s rapid growth will soon lead it to become a major source of demand for products made by U.S. workers. Here, however, is more evidence that that hope may be vain—that China is already running into the middle-income growth trap. Read The Economist, “A triple shock slows China’s growth,” in which the magazine writes: “From the sublime to the subpar: A triple shock slows China’s growth: Power cuts, the pandemic and a property slowdown: all have taken a toll.”

Dispatch from EconCon 2021: Addressing racial and gender stratification in the U.S. economy is key to an equitable and sustainable recovery

The 2-day EconCon 2021 conference, held virtually from October 6–7, featured speakers, panelists, and moderators from across the progressive policy and academic landscape. They were tasked by the co-hosts of the event, including the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, with examining “once-in-a-generation policy changes and transformative investments” to address U.S. economic inequality perpetuated most severely by the consequences of racial and gender stratification stretching back centuries and hobbling the U.S. economic recovery to this day.

The co-hosts put together an engaging schedule specifically to “underscore how fragile and unequal our economy has been, especially for communities of color, women, and other vulnerable people” in the wake of the coronavirus recession and the continuing pandemic in order to raise up policy solutions to “ensure an equitable, full recovery and a stronger, more sustainable economy for the future.” One central theme within this broad conference template that rose to the fore of the discussions were three words penned last summer by Janelle Jones—now the chief economist at the U.S. Department of Labor and previously a leader at Groundwork Collective, the leading co-sponsor of the EconCon 2021 event.

Those three words—“Black Women Best”—underpin Jones’ observation that when those who are last to recover from economic recessions—Black women—prosper equitably in the U.S. economy, then everyone will prosper in the process. These three words were repeated in multiple sessions and fireside chats over the course of the 2-day event.

One of the sessions, titled “Centering Black Women in our Economic Recovery to Ensure a Full Recovery for All,” zeroed in directly on this issue. The panel featured Taifa Smith Butler, Rebecca Dixon, and Michelle Holder—three Black women who are executive leaders of nonprofit organizations in the nation’s capital. Holder, the president and CEO of Equitable Growth, opened this session by fielding a question from moderator Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman, one of the co-founders of Sadie Collective: How are women of color experiencing the U.S. economy amid the pandemic?

Holder set the scene by noting that Black women on average earn the lowest wages and salaries yet can boast the highest rate of labor force participation in the country. She said this “conundrum” is the result of past racial and gender stratification, amplified over the centuries and exacerbated by the coronavirus recession and ongoing pandemic. The legacy of Black women’s enslavement, conditioned by their “exclusion from the cult of domesticity” embraced by White society for only White women in the post-Civil War era, especially in the Jim Crow South, still influences Black women’s employment and wealth-creating opportunities in the present.

“Black women kept working,” said Holder of the post-slavery era extending into today’s modern economy. “Black men were earning so little that Black women had to work to make ends meet,” she added. Similar conditions prevail today, where Black women, more often than White women, are either co-breadwinners or the primary breadwinners in their families.

Holder then juxtaposed Black women’s “strong attachment to the U.S. labor force” even when they earn the least in the U.S. economy, noting that they disproportionately hold the low-wage jobs that are now the most disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic. Given that a third of women who work in the United States are mothers, and that about 66 percent of Black children are raised in single-parent homes primarily by single moms—compared to about 25 percent of White children—disruptions to, or lack of, child care options raise particular challenges for Black working moms.

Holder’s co-panelist Rebecca Dixon at the National Employment Law Project added that Black women are held back in the U.S. economy because 90 percent of occupations are racially segregated due to the historical legacy of not just slavery but also sharecropping, property market redlining, and the agricultural and domestic work they did that was excluded—and still is excluded among some care professions—from Social Security. This occupational segregation, Dixon said, “is a perfect Venn diagram of discrimination past and present.”

Holder put a number on the cost of this gender and racial wage divide, which she terms the “double gap”: $50 billion a year in involuntarily forfeited earnings by Black women. This $50 billion (measured in 2017 dollars) probably accrued to a mix of corporate shareholders and executives, and to some extent to White workers, she said, though the breakdown isn’t clear. But the result is that Black women earn 60 cents on the dollar of what White men earn in the U.S. economy today.

Dixon then pointed out that the joint federal-state Unemployment Insurance program adds economic insult to discriminatory injury because Southern state UI programs were “in tatters” even before the pandemic; the majority of Black Americans currently live in the U.S. South.

Taifa Smith Butler of Demos then fielded a question from the Sadie Collective’s Opoku-Agyeman on policy solutions for this “double gap.” Smith Butler said that U.S. policymakers need to “reimagine economic democracy to give Black women the agency to make their own decisions without systems of oppression in place.” Black women, she said, need to get off the “hamster wheel creating wealth for other people.”

Holder then suggested a way to measure the economic well-being of Black women in the United States, harkening back to Janelle Jones’ “Black Women Best.” Holder said U.S. policymakers need to pay close attention to race and gender data on Black female employment and implement measures that move the country in the direction of more wage transparency in workplaces. Smith Butler added that disaggregation of employment and earnings data along race and gender lines must also be broken out by region.

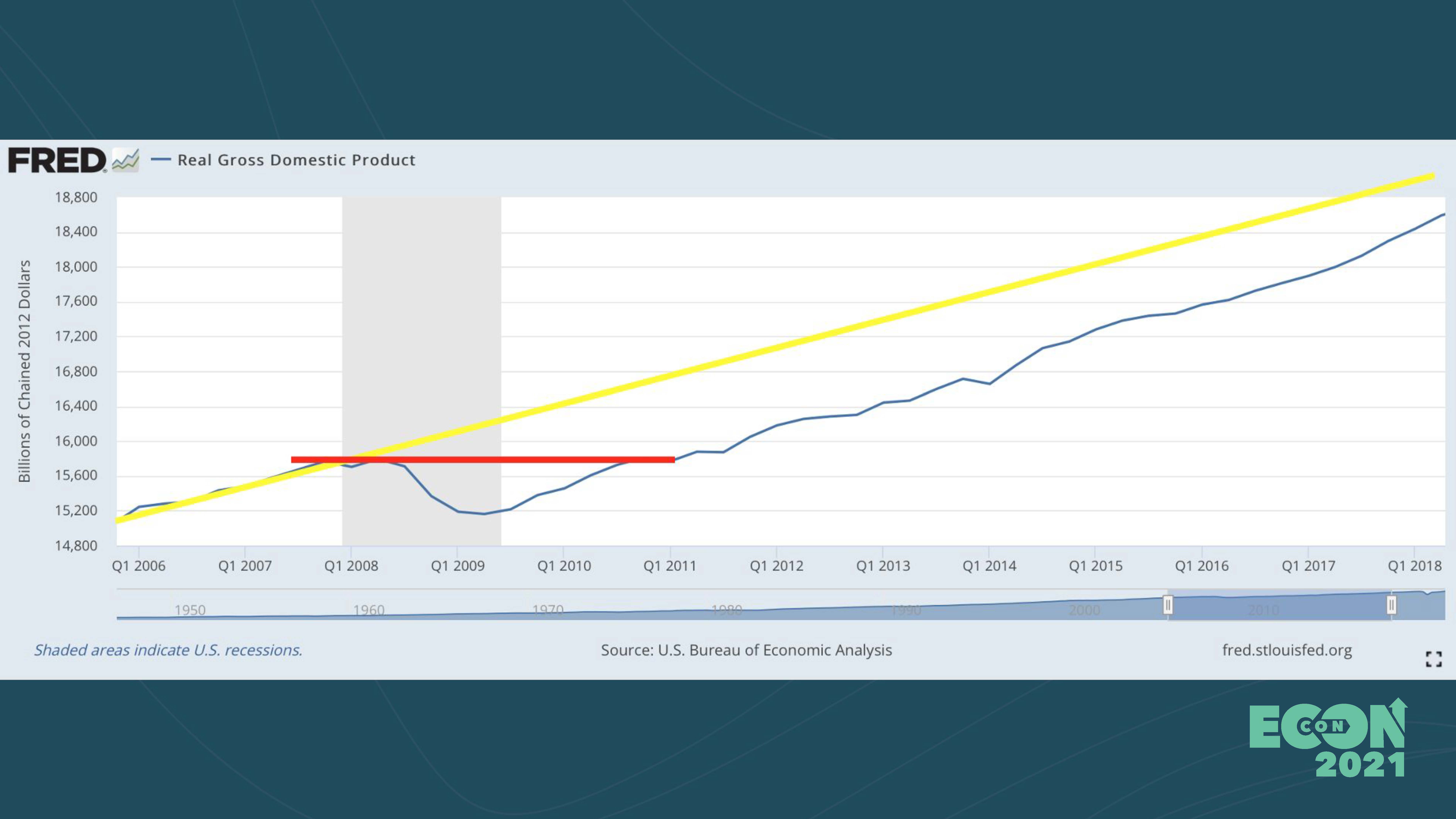

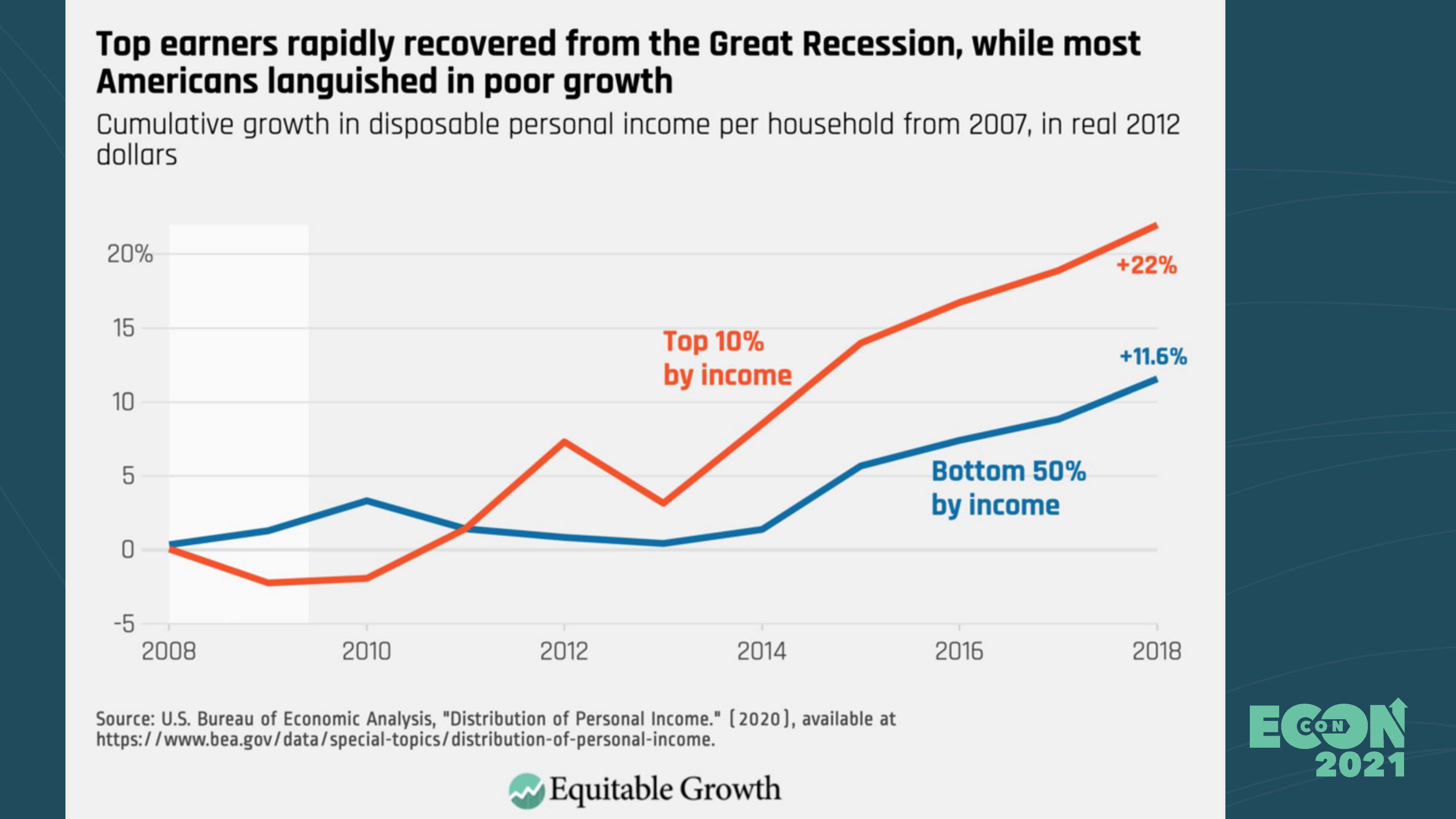

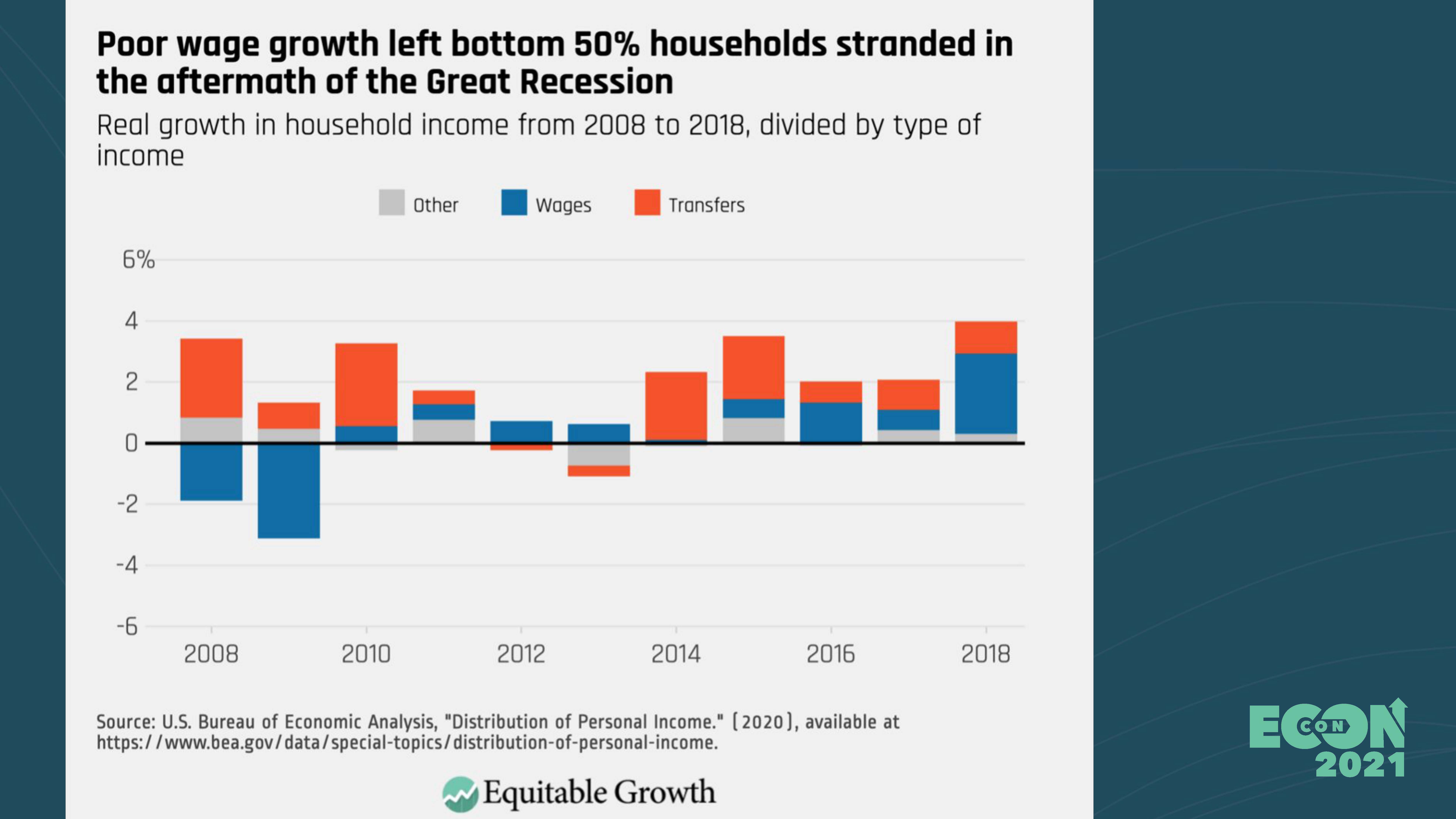

An important session on the second day of the conference added critical details to the need for economic data disaggregation by race, ethnicity, and gender in all its forms. The session, titled “Defining Success: Reimagining Data Measurement,” was moderated by Equitable Growth Director of Economic Measurement Policy Austin Clemens, with panelists Algernon Austin of the Center for Economic and Policy Research and Tracey Ross of PolicyLink. Austin set the table with three figures showing the inequitable economic recovery from the Great Recession of 2007–2009. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The three slides show various dimensions of the slow recovery from the Great Recession to put the coronavirus recession of 2020 and its aftermath in focus amid today’s uneven economic recovery and continuing pandemic. Clemens and the two panelists then dove into a discussion of the indicators of racial stratification that are essential to discern in U.S. economic data, so that policy solutions can be identified to create strong, broad-based economic growth across the country. They all noted that there can be no understanding of persistent and rising economic inequality without acknowledging racial, ethnic, and gender inequality.

PolicyLink’s Ross said that policymakers, economists, and the press alike “need to reframe what it means to recover” from the coronavirus recession, so that “it’s not just back normal, which was not good enough for too many people.” Recovery, she said, needs to be about “fixing the broken economy, focusing on Black unemployment as one metric, on rural healthcare as another, and other indicators that show that the U.S. economy and society are stronger than they were before going into the crisis.”

The Center for Economic and Policy Research’s Austin noted that policymakers can’t improve what isn’t measured, and what is measured and reported on by the press doesn’t “reflect the lived experiences of average Americans.” He says that federal economic statistical agencies need to move away from average measures and adopt disaggregated ones that will capture more telling trends in Black workers’ employment rates. “Recovery is not the goal post, as that was a society with deep inequalities,” he said. “The Black unemployment rate goes from high, to really high, to high. It never goes to low.”

Clemens, Ross, and Austin discussed other key measures to capture the extent of racial stratification in the U.S. economy and then measure the results of new policy solutions in the subsequent data. They suggested a variety of new metrics, among them housing affordability disaggregated by race and income and by home rental and purchase prices, as well as a breakout of employment by wage category to see when low-wage jobs are recovering, compared to the already-recovering high-income and middle-income jobs. Then, there is the simple measure of paid sick leave. “Everyone is better off if everyone can get paid sick leave,” said Austin.

The panel ended with a discussion on regional economic inequality and its intersection with the baleful consequences of climate change on communities of color in particular. Clemens noted that the federal statistical agencies don’t always have the statistical power to monitor poverty and other economic outcomes in small geographic areas. And Austin pointed to racist and historically anti-Black policies in Mississippi that cascade across high levels of poverty and inequality, and are then exacerbated by poor infrastructure investment in mitigating climate change, which is causing more heat- and asthma-related health problems and more flooding that disproportionately harms Black Mississippians.

All in all, the 2 days of discussion and generation of policy ideas underscored the need for policymakers and economists alike to embrace new measures of economic inequality to understand how structural racism manifests in policies and institutions, and how this deep racial stratification in the U.S. economy and society can be reversed to create a stronger and more sustainable economic recovery for everyone.

As Tracy Williams of the Omidyar Network (another co-host of the event) said when opening one of the first sessions of the conference, “a key part of reimagining capitalism is to center Black women inside an equitable economy.” EconCon 2021 went a long way toward making the case that a smart way to define that success is to understand and measure how Black women are experiencing economic prosperity.

Supporting American Indian tribal sovereignty boosts economic outcomes for those on reservation lands

American Indian communities over the past 30 years experienced more economic growth and improved well-being than during any other point in the more than five centuries since European colonists and settlers arrived on this continent. These improved outcomes are largely a result of increased exercise of tribal sovereignty and self-governance, which created new opportunities for Americans Indians, as well as non-American-Indians living on or near tribal lands and resources.

Yet despite these gains, tribal governments still face obstacles to fully realizing economic and political opportunities for their citizens. Though poverty and unemployment rates fell during the past three decades, many American Indians still face significant economic challenges, as income inequality increased and income mobility stagnated. Identifying and addressing these issues is also made difficult because there is surprisingly little economic research on Indigenous people living on reservations in the United States. This means researchers don’t have access to data that accurately reflect the economic conditions and realities of many American Indians.

An upcoming virtual event hosted by Equitable Growth on November 3 will explore how to stimulate economic activity on tribal lands and improve the well-being of American Indians and how these policies can strengthen climate mitigation and resilience efforts. The event, titled “Supporting tribal sovereignty and resilience for American Indians in the 21st century,” will feature Equitable Growth grantee and associate professor of public policy and American Indian studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, Randall Akee.

Akee (Native Hawaiian) will be joined in the conversation with:

- Dwanna L. McKay, assistant professor of race, ethnicity, and migration and Indigenous studies at Colorado College (Muscogee)

- Christina E. Snider, tribal advisor in the office of Gov. Gavin Newsom (Dry Creek Pomo)

- C. Matthew Snipp, The Burnet C. and Mildred Finley Wohlford professor of humanities and sciences at Stanford University and an Equitable Growth grantee (Oklahoma Cherokee/Choctaw)

The event builds on Akee’s contribution to Equitable Growth’s compilation of essays, Boosting Wages for U.S. Workers in the New Economy, which presents ideas for raising wages across the U.S. labor force by addressing underlying dynamics in the economy. Akee’s chapter dives into and contextualizes his previous research and details many of the issues the event will touch upon, from improving data quality and collection efforts—an especially urgent and critical issue during the coronavirus pandemic—to tribal sovereignty and its impact on economic outcomes for American Indians on reservations.

Some of the specific policies he recommends are to create new and innovative industries on tribal lands, to enact a tribal jobs guarantee program, to invest and expand infrastructure on tribal lands, and to increase access to capital, among other ideas. These efforts also could reinforce large-scale climate mitigation projects, renewable energy generation, and ecosystem restoration programs in tribal nations.

In addition, Akee makes plain that without added investments to create new longitudinal datasets that expand survey samples and gather and disaggregate more data from Indigenous populations, it will be next to impossible to evaluate the efficacy and results of these policies.

These policy ideas are essential to continuing the past 30 years of improvements in the general well-being of American Indians residing on reservations. They also would work to improve outcomes for non-American-Indians living on or near tribal lands, thus boosting economic conditions in many rural and underdeveloped regions of the United States that, for the past few decades, have been struggling with deindustrialization, stagnant wages, and rising unemployment.

Equitable Growth’s upcoming event will gather policymakers, researchers, and advocates for an informed discussion of these topics. It will also provide a valuable opportunity to understand how these ideas can be tied to climate change mitigation—an increasingly important issue for policymakers as more and more people experience the effects of a rapidly warming climate.

For more information about the event, which will take place virtually on November 3 from 1:30 p.m. – 3:00 p.m. EDT, visit the Equitable Growth event page. To register for the event and access additional details on speakers and the agenda, click here.

Equitable Growth scholars highlight the need for broad investment in U.S. social infrastructure

Our nation’s social infrastructure is composed of the economic and social investments that are necessary for U.S. workers and families to be able to take care of their loved ones and remain productive members of the U.S. workforce. Social infrastructure is an essential support system for workers in the United States that enables the rest of the economy to function. Yet the nation has long underinvested in it. This policy choice leaves workers to fend for themselves in times of health or economic crises. They face impossible choices between their loved ones and their livelihoods, which ripple out to affect the broader economy.

As the debate continues on the size and scope of social infrastructure investments to include in the Build Back Better Act now under negotiation in Congress, Equitable Growth today released a new essay on the need for policymakers on Capitol Hill to boost investments in social infrastructure. The essays, penned by two of the nation’s leading experts on social and economic policy—Liz Ananat of Barnard College and Anna Gassman-Pines of Duke University—is the latest in a series of pieces by Equitable Growth scholars making the case for robust social infrastructure in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

Highlighting an extensive body of research on the benefits of social infrastructure programs for workers and the overall economy, these scholars make a compelling case: For the United States to emerge from the pandemic in a stronger economic position than it entered it, policymakers must make substantial investments in the nation’s social infrastructure. This includes income support for families, U.S. child care and early education systems, home- and community-based services and supports for older adults and people with disabilities, and a comprehensive paid leave program.

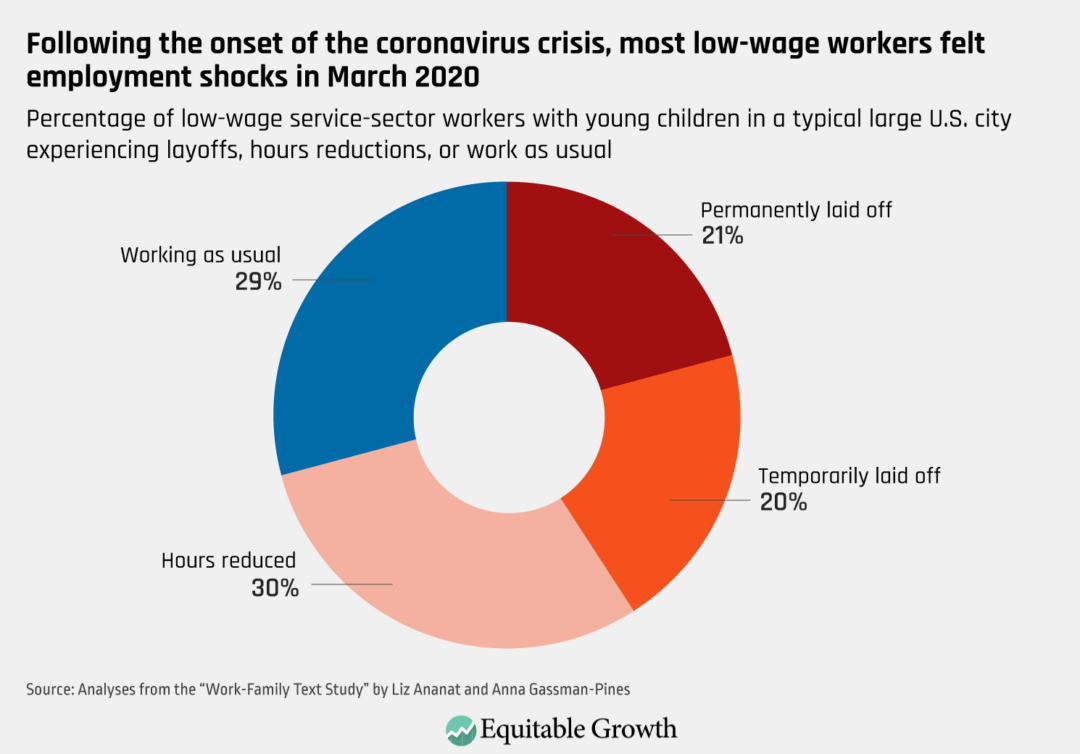

In May 2020, Ananat and Gassman-Pines authored a New York Times op-ed that shared results from their Work-Family Text Study, launched in February 2020. The study collected daily surveys administered by text messages to 1,000 service-sector workers in Pennsylvania who have young children to look at the effects of a stable scheduling ordinance on their well-being. Their results paint a picture of severe employment disruption in March, and “by the end of April,” they wrote, “only 20 percent were working as usual.” (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

In their new Equitable Growth essay, they pick up where they left off, describing the struggles many of these workers reported facing between their work responsibilities and caring for their families. These challenges were especially pervasive amid care disruptions and school and care center closures resulting from the pandemic. Indeed, they write, “1 in 7 of our respondents are responsible for an elderly or disabled loved one, and nearly a quarter of those lost the help they had to care for them,” while 77 percent of respondents had to reshuffle work schedules to care for their children.

Ananat and Gassman-Pines’ work highlights the twin roles of people as workers and as caregivers for family members both old and young. They note that “our economy will be stronger and our families will be more secure tomorrow if we invest in care today,” and also point to an existing policy success to build on: After Congress enhanced the Child Tax Credit earlier this year, food security was cut in half among receiving families.

Our economy will be stronger and our families will be more secure tomorrow if we invest in care today.

Liz Ananat and Anna Gassman-Pines

Investment in child care and early education is a crucial piece of investment in care as well. In an op-ed piece in New Hampshire’s Union Leader, Dartmouth College’s Kristin Smith notes that“child care providers are among the lowest-paid workers in the United States. Individuals in paid care jobs earn less than other workers with similar credentials, characteristics, and demographics.” Yet this work makes so much other work possible. Smith writes that “when 860,000 women left the labor force in September 2020, the essential role that teachers and child care providers play in supporting women’s labor force participation became indisputable.”

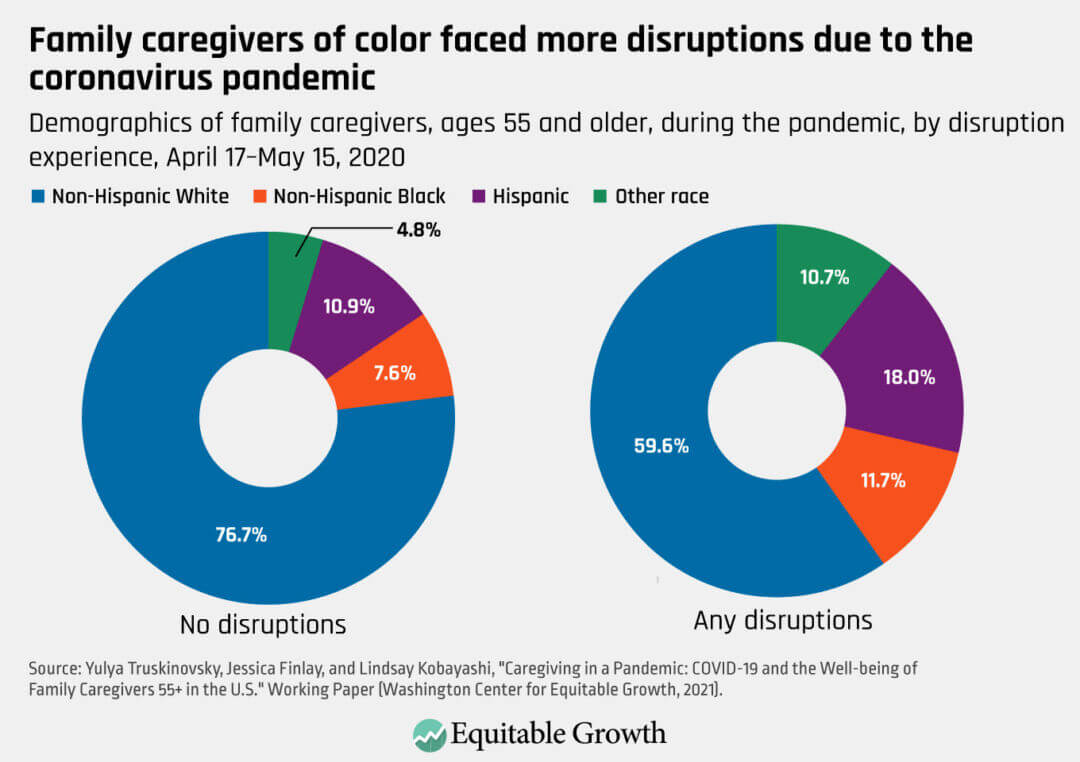

It’s not just U.S. child care infrastructure that needs investment. As economist Yulya Truskinovsky at Wayne State University notes in her June 2021 Detroit News op-ed, caregiving arrangements for older adults and people with disabilities “were precarious even before the pandemic. Turnover among direct care professionals was high due to low wages and poor job conditions, including high rates of workplace injury.”

In a related Equitable Growth column summarizing her working paper with Jessica Finlay and Lindsay Koyabashi of the University of Michigan, Truskinovsky notes that disruptions to fragile caregiving arrangements were prevalent during the pandemic and that “those caregivers who provided more care because of the pandemic—disproportionately women and people of color—were almost 19 percentage points more likely than noncaregivers to report an impact on their employment.” (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Truskinovsky calls for a federal paid leave program, which would provide up to 12 weeks of paid leave for workers who need time off to care for a loved one with a serious medical condition. She also proposes improvements in improving pay and working conditions for professional caregivers, who provide community-based services and supports to people with serious medical needs year round. Both are essential to ensure that older adults and people with disabilities get the support they need and that their loved ones can fully participate in the paid labor force.

Three other Equitable Growth scholars have also weighed in on the importance of paid leave in the pages of U.S. newspapers. In her op-ed in the Union Leader, Dartmouth College’s Smith writes, “My research shows that nearly 80 percent of New Hampshire residents support a paid family and medical leave insurance program, though such a program does not exist—yet.”

In the pages of the Portland News, Julia Goodman of Portland State University and Danny Schneider of Harvard University describe their fall 2020 survey of 8,500 workers at 125 of the largest service-sector firms in the nation, writing that “Thirteen percent of workers reported they had needed to care for someone else with a serious medical condition. And 4 percent of workers told us they welcomed a new child in the past year. Yet two-thirds of these workers, and nearly 1 in 5 front-line service-sector workers, told us they couldn’t take the leave they needed.” They quote one worker, who explains simply that “We don’t make money if we don’t work. To survive we must work sick!”

Over the past 18 months, it has become ever more clear that U.S. social infrastructure policies form an economic backbone that is just as powerful as the one provided by roads and bridges. But just as there are many components necessary to make physical infrastructure function, social infrastructure cannot work in isolation.

A new parent needs paid leave and child care to stay in the labor force and a monthly payment from the fully refundable Child Tax Credit to keep their children in diapers. A worker whose sibling experiences a traumatic brain injury needs paid leave to make arrangements after the injury occurs and community-based services and supports for their sibling when they return to work. To become a productive participant in the economy, a child needs care in the first years of life, preschool to prepare them for Kindergarten, and funds from the monthly fully refundable Child Tax Credit to ensure that they have the school supplies they need through their teenage years.

Since the early days of the pandemic—and indeed long before the pandemic occurred—these leading scholars have been conducting rigorous research that uncovers the need for a serious investment in the many crucial facets of the nation’s social infrastructure. They provide the evidence that makes the urgency of this moment impossible to ignore.

Though the research they do and the policies they discuss differ, one theme shines through them all: To emerge from this pandemic stronger, the United States needs substantial and bold investment in the people—the workers, families, and caregivers—that drive the U.S. economy.

Evidence shows that now is the time to invest in U.S. workers and their families

In February 2020, we set out to examine the effects of a new predictable scheduling ordinance in eastern Pennsylvania on low-wage service-sector workers. We had no idea that the workers we were studying would end up on the front lines of a global pandemic, that we would get a window into their work keeping Pennsylvanians’ refrigerators stocked and basic needs met, or that the national conversation would shift to seriously consider how current U.S. social infrastructure is woefully inadequate for many of these workers and their families.

As we began texting daily surveys to 1,000 service workers with young children to learn about their experiences, we heard over and over again about the near-impossibility of fulfilling caregiving responsibilities at home while upholding job responsibilities at work.

Our research points to one clear way to support the essential workers who kept the U.S. economy running through the darkest days of the coronavirus pandemic that would also serve to strengthen the economy so that the United States emerges from the COVID crisis stronger than it entered it: Invest in the nation’s social infrastructure.

While essential workers continued to show up for work and helped everyone else take care of their families, these workers struggled to manage their own care responsibilities. Last fall, 77 percent of our survey participants reported dealing with sudden school or child care closures that forced them to reshuffle work, while 12 percent reported having to leave the labor force to care for their children. Likewise, 1 in 7 of our respondents are responsible for an elderly or disabled loved one, and nearly a quarter of those said they have lost the help they had to care for them.

“Since the pandemic, things have been really tough,” said one participant. “[We’ve been] making hard decisions whether to stay home or work to care for family.” Another study participant remarked, “We fell short on money and became completely depressed … [M]y mother who lives in the home with me was put on hospice due to brain cancer, so it’s one crisis after another.”

The truth is, families across the country were already being forced to make impossible decisions to navigate work and family conflicts before the pandemic began. To manage the nighttime and weekend hours that many jobs demand, for instance, workers need access to affordable, dependable child care, and they need to be able to count on professional, home-based care providers that support family members with disabilities and chronic health conditions.

Yet these services alone cannot address the range of unexpected emergencies that can worsen work-life conflicts. Workers in our study often reported being forced to choose between addressing a health need and paying rent. They are not alone. All over the country, families are struggling to manage their caregiving responsibilities, with the burden primarily falling on women workers, who continue to see declines in employment even as men return to work.

To ensure that U.S. families have the support they need, and that employers can hire the workers they need, Congress must invest in our nation’s social infrastructure. This means investing in child care and community-based services and supports for older adults and people with disabilities. It means ensuring that families with children can continue to access income support through the monthly fully refundable Child Tax Credit. And it means enacting a permanent paid family and medical leave program, so that all working people have access to at least 12 weeks of paid leave.

These are smart, safe investments. Research shows that in places where paid leave has been implemented, businesses benefit along with their workers. Employers in states with paid leave are largely supportive of these programs, saying such laws make it easier to handle employee absences when the need for leave occurs. And according to other research, paid leave helps families support their elders in staying in their homes and out of care facilities—a win-win for families and for taxpayers.

Federal policies helped stabilize the U.S. economy and ameliorate families’ struggles during this pandemic. Indeed, temporary reforms to the Child Tax Credit enacted in January have alone already halved food insecurity among families who received it. But for the United States to emerge stronger from this crisis, we need permanent reforms to ensure our nation’s workers can care for their families. As one parent in our study noted, “We are okay, but the whole situation has left us uncertain of the future; financially, emotionally, and health-wise. I still hold out hope that our future is bright.”

A brighter future is possible. But Congress must first invest in our nation’s social infrastructure. It has the chance now, as Congress discusses the social infrastructure programs that are core components of the Build Back Better Act. Our economy will be stronger and our families will be more secure tomorrow if we invest in care today.

Brad DeLong: Worthy reads on equitable growth, October 13-18, 2021

Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

1. Our Expert Focus series this month tells you why you should be paying attention to the extremely sharp Francisca Antman, Mónica García-Pérez, Mark Hugo López, G. Cristina Mora, and Eileen V. Segarra Alméstica. Read Aixa Alemán-Díaz, Christian Edlagan, and Maria Monroe, “Expert Focus: Latino leaders in economics and a call for more data & research about Latinos and Hispanics,” in which they right: “Equitable Growth is committed to building a community of scholars working to understand how inequality affects broadly shared growth and stability. To that end, we have created the monthly series, ‘Expert Focus.’ This series highlights scholars in the Equitable Growth network and beyond who are at the frontier of social science research. … In honor of Hispanic Heritage Month, this installment of Expert Focus highlights Latino leaders in economics, the need for more, and more accurate, data about Hispanics and Latinos, and research that applies the intersectionality of race, ethnicity, and gender from among Equitable Growth’s academic community and beyond.. … Francisca Antman… Mónica García-Pérez … Mark Hugo López … G. Cristina Mora … [and] Eileen V. Segarra Alméstica.”

2. I remember, long ago, the wise Federal Reserve staffer David Wilcox telling me that he had realized that nowcasting was both the most difficult and most important part of his job. This looks to be an excellent forthcoming event on the current state-of-the-art here. Read about the forthcoming event, “Equitable Growth Presents: Opportunities and challenges of real-time economic measurement,” in which the participants will discuss: “The coronavirus recession led to a crop of economics working papers trying to understand the effects of the pandemic in real time. This research responded to a pressing policy need: Policymakers were prepared to spend hundreds of billions of dollars to staunch the losses of the pandemic, with relatively little knowledge of how to effectively target the money. Work by economists looked at poverty during the pandemic, how people were using stimulus checks, the impacts of enhanced Unemployment Insurance, and much more. The incredibly short turnaround time of much of this research was unprecedented for the profession. The severity of the COVID-19 crisis, the availability of administrative data sources, and new statistical tools combined to produce an enormous amount of nearly real-time data on the economic health of U.S. families. This event convenes experts on the analysis and application of real-time data to discuss what we learned over the past 18 months. Though future crises may not cause the precipitous economic gyrations that the coronavirus did, the lessons economists are learning now may help us respond more effectively to future recessions, guiding policymakers’ response to the next recession by using empirical results from the current one. Speakers [include] Austin Clemens, Director of Economic Measurement Policy, Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Erica Groshen, Senior Economics Advisor, Cornell University. Jeehoon Han, Assistant Professor, Zhejiang University. Dana Peterson, Chief Economist, The Conference Board.”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

1. The Economist has an excellent interview with two of our three Nobel Prize winners this year—David Card and Josh Angrist. If you want to know why we economists respect them so much and are cheering their Nobel Prizes so loudly, read, “A real-world Revolution in Economics,” in which the magazine says: “THIS YEAR’s Nobel prize celebrates the ‘credibility revolution’ that has transformed economics since the 1990s. Today most notable new work is not theoretical but based on analysis of real-world data [and] … How their work has brought economics closer to real life.”

2. This is better than 99 percent of the things that crossed my screen on inflation these days. Remember: you cannot rejoin the highway at speed without leaving rubber on the road, and so you should not be alarmed when you do so—unless, of course, you really do not want to rejoin the highway at speed at all. Read Claudia Sahm, “Inflation is not the emergency,” in which she writes: “Fast forward to today, and surging prices are behind us. That’s a step back to normal. Monthly inflation—a better indicator of current conditions than year of year—peaked in June 2021. In September, inflation excluding food and energy, was back near its pre-Covid average. Total inflation is higher, but food and energy prices tend to be more volatile and, as result, often tell us less about where inflation is headed. Supply chains and commodity prices remain a thorn in the side of consumers and businesses. As with jobs, progress is progress, even when it’s slower than we want. Demand matters for inflation too. This year spring demand surged. In fact, in April and May of 2021, the highest percent of consumers, on net, said it as a good time to buy big-ticket durables since the crisis began. That coincided with the surge in inflation. Now that measure of demand is lower than the depths of the recession. Again, it’s hard to see a spiral inflation taking hold when consumers are willing to wait it out until inflation settles down, as they expect it will. … Inflation is not an emergency, but getting the pandemic under control is.”

3. This is, I think, the best single thing to read about the Economics Nobel Prize for Card, Angrist, and Imbens. Read Noah Smith, “The Econ Nobel we were all waiting for,” in which he writes: “To predict who will win the Econ Nobel … list the most influential people in the field who haven’t won it yet [and] … Assume … micro theorists won’t win … two years in a row. … The ones whose influence is the oldest are the most likely to win. … For years, this method led lots of people—including me—to predict a Nobel for David Card. His 1994 paper with Alan Krueger on the minimum wage was a thunderbolt. … Since then, Card has been at the forefront of empirical labor. … Angrist and Imbens’ impact … though also huge … came later. … I wouldn’t have been surprised had they won the prize in later years. But Card was clearly overdue. Perhaps the reason it took this long was that Card’s conclusions in his famous minimum wage paper were so hard for many in the field to swallow. … At the time, Card and Krueger’s finding seemed revolutionary and heretical. In fact, other researchers had probably been finding the same thing, but were afraid to publish their results, simply because of their terror of offending the orthodoxy.”

Weekend reading: Why stable schedules matter edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

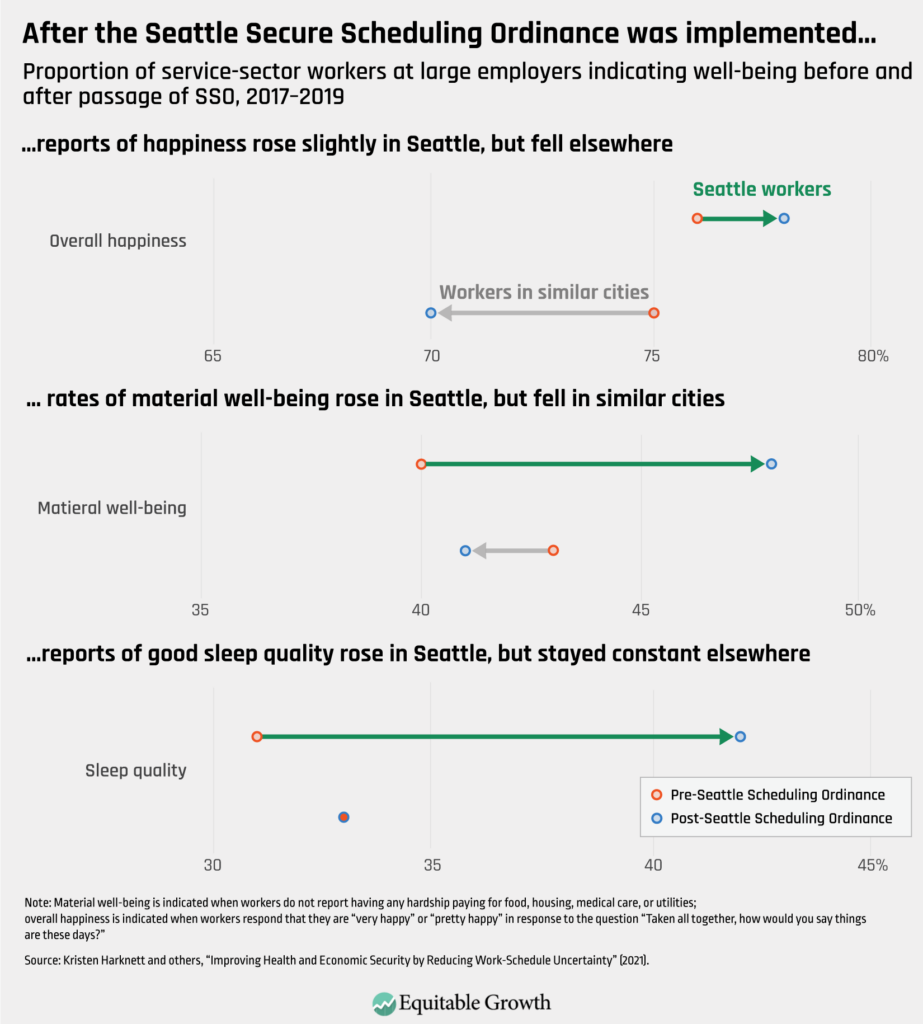

Long before the coronavirus pandemic reached the United States, policymakers were discussing schedule quality and stability for service-sector workers. In fact, nine cities and states have passed fair workweek laws to improve schedule predictability in the service sector, inspired by a large body of work showing positive outcomes for both individual workers, company bottom-lines, and the broader economy. A new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, dives into this topic, looking at the effects of a stable scheduling law passed in Seattle in 2017. Alix Gould-Werth, Raksha Kopparam, and I detail the research findings and contextualize them in the existing literature on schedule quality. The new study, we write, finds that the Seattle Secure Scheduling Ordinance reduced the prevalence among service-sector workers of schedule instability or unpredictability—defined as having less than 2 weeks’ notice of an upcoming work schedule, not being compensated for last-minute schedule changes, and working on-call or clopening shifts. It also finds notable improvements in worker well-being outside of work, including material hardship, stress levels, and sleep quality. The study is a fascinating addition to the existing research and suggests that policymakers should heed the evidence on the myriad benefits of ensuring workers have access to predictable, stable, and good-quality schedules.

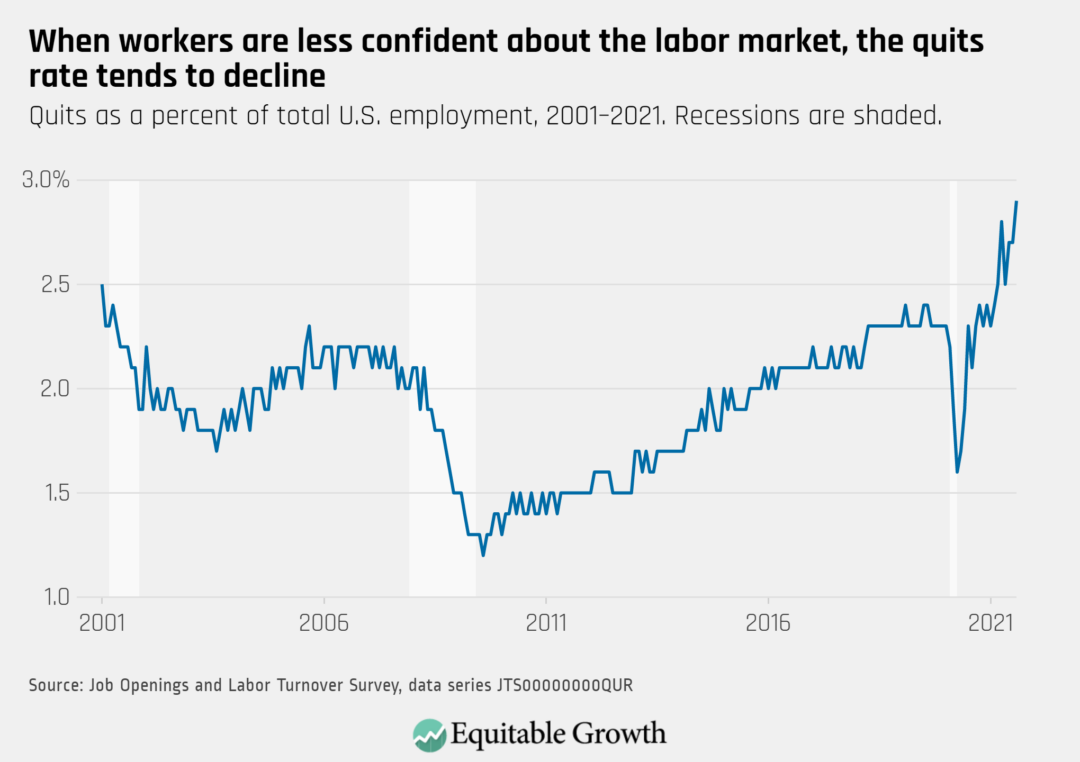

This week, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released August 2021 data on hiring, firing, and other labor market flows from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, better known as JOLTS. This report doesn’t get as much attention as the monthly Employment Situation Report, but it contains useful information about the state of the U.S. labor market. Kathryn Zickuhr and Carmen Sanchez Cumming put together five graphics highlighting key findings in the data, including that the quits rate rose to almost 3 percent as nearly 4.3 million workers left their jobs. This signals higher worker confidence about the state of the U.S. labor market.

Every month, Equitable Growth staff highlights the work of scholars on the forefront of social science research in a series called “Expert Focus.”This month, Aixa Alemán-Díaz, Christian Edlagan, and Maria Monroe feature the work of Latino leaders in economics and the social sciences. They touch upon the need for more, and more accurate, data about the Hispanic and Latino populations in the United States, as well as research at the intersection of race, ethnicity, and gender. They also discuss the important mentorship and training programs—such as the American Economic Association and the American Society for Hispanic Economists—that are working to attract and retain individuals from underrepresented backgrounds to the field of economics.

ICYMI: Equitable Growth has officially ratified a collective bargaining agreement with the Nonprofit Professional Employees Union, IFPTE Local 70. It was ratified on August 14 and includes improvements in pay equity, paid time off, and retirement contributions, among other things.

Brad DeLong highlights some must-read content from Equitable Growth and around the web in his latest Worthy Reads column.

Links from around the web

Last Friday’s jobs report numbers were much lower than expected—194,000 jobs were added, when many analysts predicted more like 500,000 would be—but The New York Times’ Neil Irwin explains why it may not be as bad as it looks. He dives into the data, writing that the numbers still show a steady expansion that is “more rapid than other recent recoveries” and that things are being held back by supply chain blockages and the delta variant of the coronavirus. This, combined with revisions for July and August numbers, suggest that the economy is entering fall in a stronger place than it seemed. Irwin analyzes various aspects of the employment report to detail why we shouldn’t get overly concerned about the lackluster numbers—yet.

A new poll reveals that almost 20 percent of U.S. households—and almost a third of those making less than $50,000 per year—lost their entire savings during the coronavirus pandemic. Bloomberg’s Simone Silvan shares the survey results, which also show that Black and Latino households were harder hit than other racial groups. Many of the respondents to the poll reported dipping into or using up their savings to cover child care expenses and health care costs. Silvan spoke with activists, who urged Congress to take quick and generous action to ensure this trend doesn’t continue and that U.S. families do not fall into poverty amid the ongoing pandemic and economic recovery.

As policymakers debate President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better agenda, and whether and how to include child care in the package, The 19th’s Chabeli Carrazana examines what child care looks like when it actually works for families. Carrazana looks into the nonprofit Chambliss Center for Children in Chattanooga, Tennessee, which has been incredibly successful, even in the face of the coronavirus pandemic, in continuing to provide day care to a growing number of children. The centers have also expanded to provide 24-hour care to help low-income parents with nontraditional schedules and have a sliding-scale cost system in which parents pay varying care fees depending on their incomes. Carrazana suggests that Chambliss could be a model for how to implement local child care programs across the United States, with its unique system of contracting out the financial and business side of each center and subsidizing costs, so caregivers are free to focus entirely on providing the best care for children. But, she cautions, without additional aid from Congress, even these highly successful child care centers face years of financial hardship and staffing challenges as a result of the pandemic.

Friday figure

Figure is from “New study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences shows schedule stability supports U.S. workers and the broader economy,” by Alix Gould-Werth, Emilie Openchowski, and Raksha Kopparam.

Expert Focus: Latino leaders in economics and a call for more data and research about Latinos and Hispanics

Equitable Growth is committed to building a community of scholars working to understand how inequality affects broadly shared growth and stability. To that end, we have created the monthly series, “Expert Focus.” This series highlights scholars in the Equitable Growth network and beyond who are at the frontier of social science research. We encourage you to learn more about both the researchers featured below and our broader network of experts.

In honor of Hispanic Heritage Month, this installment of Expert Focus highlights Latino leaders in economics, the need for more, and more accurate, data about Hispanics and Latinos, and research that applies the intersectionality of race, ethnicity, and gender from among Equitable Growth’s academic community and beyond.

Many Latino leaders call for more accurate and representative research about Latinos. More and better data will enhance researchers’ ability to compare and/or distinguish Latinos from other groups of diverse backgrounds in the United States, as well as understand differences within the Latino community. Similarly, scholars insist on adding more context to the use of different terms, such as Hispanic or Latino. Some note the invention of Latino and Hispanic terms, as well as the ethnoracial politics and the generational differences within the group in terms of how to self-identify. Other terms used by those in this group are Latinxs and Afro-Latinos.

In economics, one way Latino leaders have drawn Latinos and individuals from underrepresented backgrounds to the profession is through their participation in mentorship programs. Below, we highlight Latino leaders working at the American Economic Association and the American Society for Hispanic Economists, which originated alongside—and often collaborates with—the National Economic Association focused on Black economists. This year, Equitable Growth participated as a first-time host organization for the AEA Summer Training Program for experiential learning participants and the AEA Summer Economics Fellows Program to support efforts to diversify the profession.

Francisca Antman

The University of Colorado Boulder

Francisca Antman is an associate professor of economics at the University of Colorado Boulder. Her research focuses on Latinos, international migration, human capital investments, and the allocation of resources within households and families. Building from development and labor economics, her recent projects examine the impact of school desegregation on the educational progress of Hispanic Americans, the construction of racial and ethnic identity and related patterns of assimilation, the effects of immigration policies on undocumented immigrants, and the effects of migration on the elderly generation left behind in Mexico. For 6 years, Antman served on the American Economic Association Committee on the Status of Minority Groups in the Economics Profession. Currently, she is serving as the co-director of the committee’s mentoring program, a flagship AEA program to attract and retain underrepresented groups in the field of economics. The program focuses on providing mentorship to early career economists and facilitating networks between scholars at all stages as a tool to advance diversity, equity, and inclusion in the economics profession.

Mónica García-Pérez

St. Cloud University

Mónica García-Pérez is a professor of economics at St. Cloud University. Her research concentrates on immigration, health economics, and labor economics. García-Pérez also is a co-author of an Equitable Growth working paper looking at credit scores and incarceration. A speaker at Equitable Growth’s Vision 2020 event, García-Pérez is also an active leader in various professional societies in economics. As past president of the American Society of Hispanic Economists, she wrote a solidarity statement in response to 2020’s historic events of discrimination, violence, and murder impacting underrepresented groups and individuals in the United States. In 2021, she served as faculty to support students interested in economics as a member of the AEA Summer Program and a fellow of the 2021 Reinventing Our Communities Cohort Program organized by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

Mark Hugo López

Pew Research Center

Mark Hugo López is an economist and the director of race and ethnicity research at Pew Research Center. He is a major voice in Hispanic/Latino data research, having led the center’s Hispanic and Global Migration and Demography research agendas for more than a decade. Drawing from his expertise on global migration and demography, Hispanic trends, and race and ethnicity, López has authored reports and short pieces on the changing demographics of Latinos and Hispanics in the United States, including how this group is impacted by the coronavirus pandemic. At Pew Research Center, three focal areas of his work involve the Hispanic electorate, Hispanic identity, and immigration. López understands the importance of having more data on Latinos to understand the nuances and trends among them through the disaggregation of data and oversampling of Latinos in federal surveys, public opinion polls, and academic research. Similar to other scholars in this installment of Expert Focus, López’s research analyzes public opinion data around the nuanced intra-Hispanic or intra-Latino perspective of the varied uses of terms, such as Latinx. Prior to joining Pew Research, López was a research assistant professor at the University of Maryland’s School of Public Policy and research director of the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement. López was a seminar speaker for the AEA Summer Program this year and serves as a mentor to the next generation of students in economics.

G. Cristina Mora

University of California, Berkeley

G. Cristina Mora is an associate professor of sociology and Chicano/Latino studies (by courtesy) and the co-director of the Institute of Governmental Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. Mora’s work highlights the need for and the important value of qualitative research for understanding the context of a specific race and ethnic group, as well as the need for the integration of this type of research into a larger debate about the disaggregation of data and oversampling, given the current racial makeup of the United States. In 2020, Mora oversaw the largest survey on the economic and health impacts of the coronavirus and COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, in California. The results shed light on the ethnoracial politics that exist within the Latino and Hispanic community and across generations. Along with Equitable Growth staff and others in academia and nonprofit sectors, Mora was part of the UNIDOSUS advisory board that published a 2021 report on closing the Latina wealth gap. The report documents the factors leading to persistent income and wealth gaps for Latinas.

Eileen V. Segarra Alméstica

The University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras campus

Eileen V. Segarra Alméstica is a professor of economics at the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras campus and faculty at the Center for New Economy, an economic policy think tank. Her work is centered on gender, race, and employment from a labor economics perspective. After Hurricane Maria in 2017, Segarra Alméstica published research about the vulnerabilities in Puerto Rico given different sociodemographic contexts among residents—low-income, those with disabilities, children and adolescents, elderly groups, those facing inadequate housing or transportation, the unemployed, and residents of different immigrant status. In 2021, she was part of a Women’s History Month panel organized by Puerto Rico’s Economists Association on the state of affairs for Puerto Rican women’s workers. Currently, Segarra Alméstica is part of the “Observatorio de la Educación Pública en Puerto Rico” (English presentation), an affiliate of the “Centro de Estudios Multidisciplinarios de Gobierno y Asuntos Públicos,” or CEMGAP, at the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras campus.

Equitable Growth is building a network of experts across disciplines and at various stages in their career who can exchange ideas and ensure that research on inequality and broadly shared growth is relevant, accessible, and informative to both the policymaking process and future research agendas. Explore the ways you can connect with our network or take advantage of the support we offer here.

JOLTS Day Graphs: August 2021 Edition

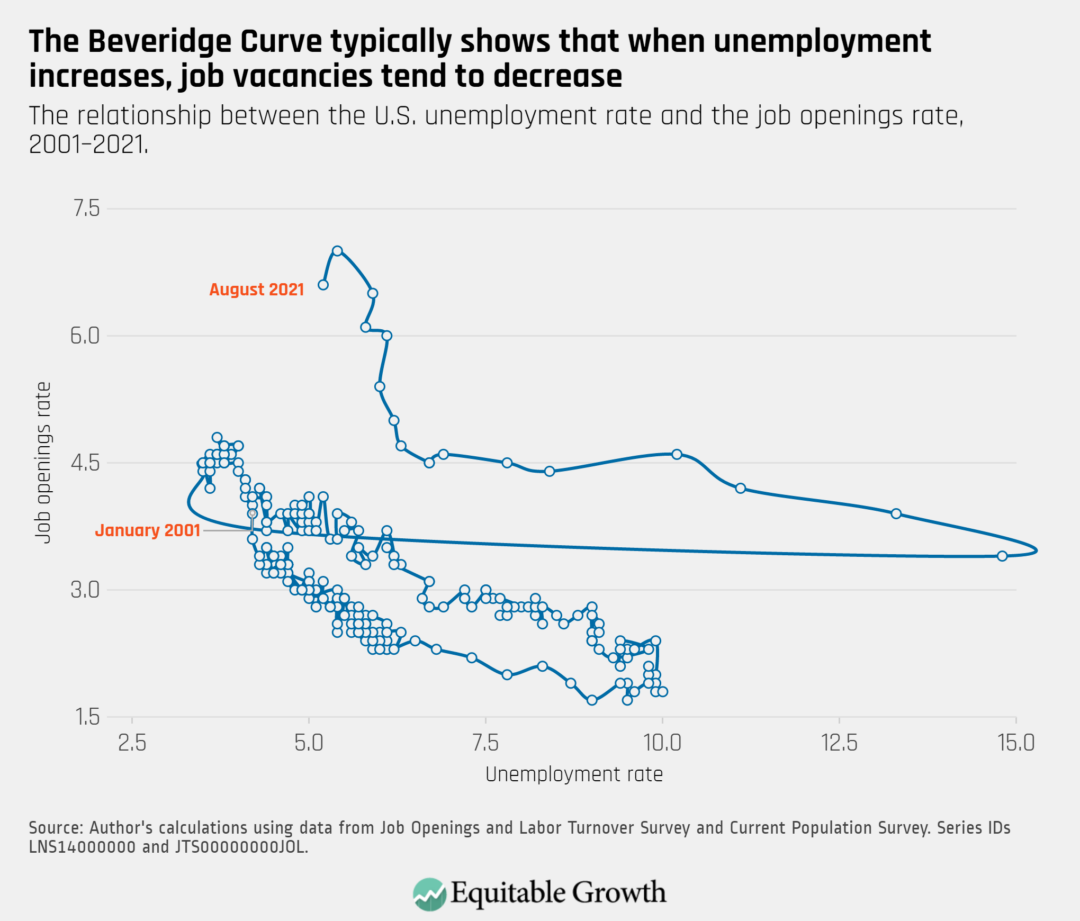

The quits rate rose to 2.9 percent as nearly 4.3 million workers quit their jobs in August, while the job openings rate decreased to 6.6 percent.

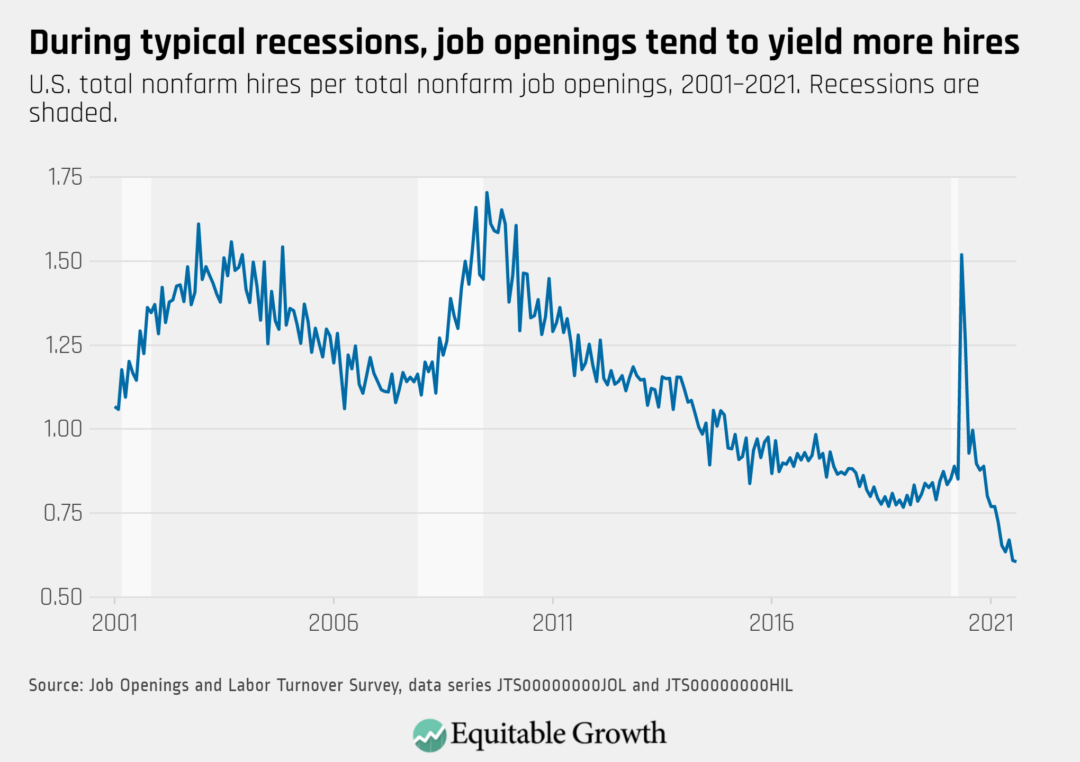

The vacancy yield declined slightly in August, remaining very low with job openings at 10.4 million—down 659,000 after a series high in July.

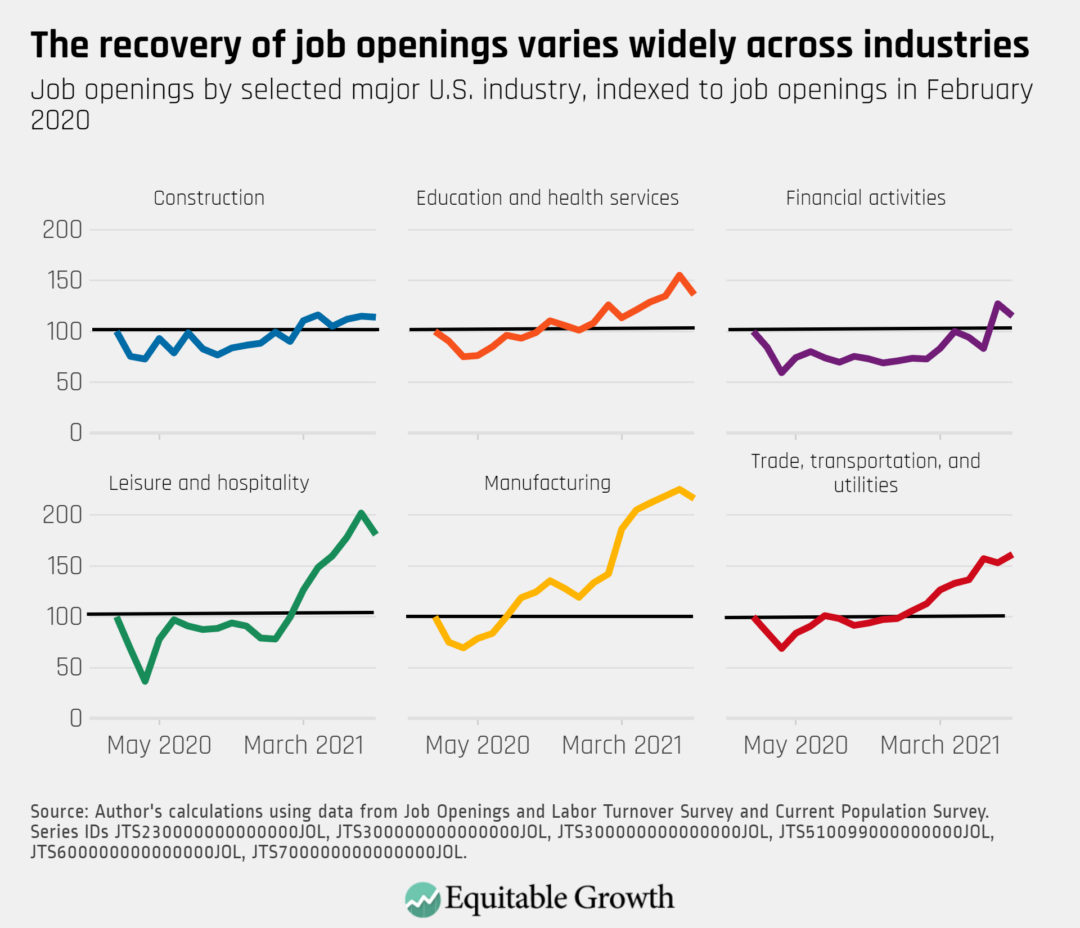

Job openings declined in August, including in sectors that had seen strong recent gains such as the education and health services, manufacturing, and leisure and hospitality.

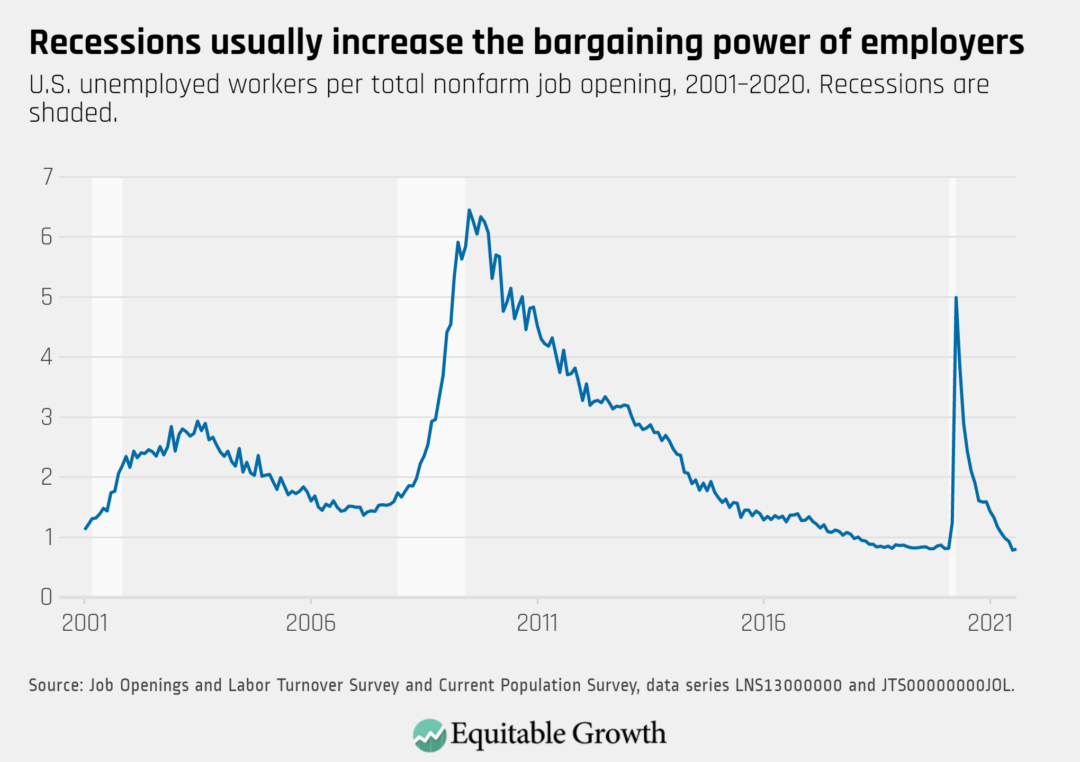

The ratio of unemployed-workers-per-job-opening increased from 0.78 in July to 0.80 in August, still similar to the low levels last seen immediately before the coronavirus recession.

The Beveridge Curve remained in an atypical, elevated range in August, with declines in both the unemployment rate and the job openings rate.