Michelle Holder, the current president and CEO of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, testified before the Joint Economic Committee of the U.S. Congress this past summer, when she was an associate professor of economics at John Jay College at the City University of New York. Her testimony is below.

Michelle Holder

Testimony before the Joint Economic Committee,

“The Gender Wage Gap: Breaking Through Stalled Progress”

June 9, 2021

Good Afternoon Chairman Beyer, Senator Lee, and Distinguished Members of the Joint Economic Committee,

Thank you for the opportunity today discuss the gender wage gap. My name is Dr. Michelle Holder, and I’m an Associate Professor of Economics at John Jay College, City University of New York. I’m a labor economist by training, and my research centers around the position and status of the Black community and women in the American labor market. In my remarks today I will focus on the impact of the gender wage gap on Black women in the United States. To do so I will largely draw on original quantitative research I conducted last year on Black women and the gender wage gap in the economic report “The Double Gap and The Bottom Line: African American Women’s Wage Gap and Corporate Profits” which I prepared for the Roosevelt Institute in NYC.

Introduction

The gender wage gap is typically a straightforward comparison of the average or median full-time wages/earnings of all working men in the U.S. and the average or median full-time wages/earnings of all working women in the U.S. According to the Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), as of June 2020, men working full-time earned a median of $1,087 per week ($56,500 annually), and women earned $913, ($47,500 annually), or about 84 cents for every dollar men earn. According to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR), in 2019 women’s median annual earnings were about 81 percent of men’s. However, this simple formulation masks complex factors which play a role in the gender wage gap; occupational crowding based on sex, gender socialization, employer bias, historical exclusionary practices on the part of unions, the “motherhood penalty,” and human capital disparities.

One prominent narrative that’s been advanced regarding the gender wage gap is that it is not due to discriminatory treatment on the part of employers in this country. Instead, the fault lies primarily with women due to voluntary choices we make. Women choose not to pursue STEM fields in college, women choose to stop out in the careers to have and raise children, women choose occupations that allow more flexibility for parenting obligations, and these occupations are inevitably lower paying. While I do not dispute that women are clearly capable of making informed choices about their careers, what I hope to show is that even when women do seemingly do all the things that should result in equitable pay outcomes there are long-held practices in American work life that leave women vulnerable to unequal pay.

If we were to rank median or average annual pay in the U.S. by race and gender, women of color, including Black women, would be at the very bottom of that rank. As of June 2020, median wages of full-time workers according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics:

White Men—$1,115 weekly, $58,000 annually

Black Men—$828 weekly, $43,000 annually

White Women—$929 weekly, $48,300 annually

Black Women—$779 weekly, $40,500 annually (70 cents for $1 for white men)

Black women earn the least due to the effects of both the “racial wage gap” (overall, Blacks earn on average less than whites in the U.S.—this is called the racial wage gap) and the gender wage gap; this is an effect I term the “double gap” in wages/earnings of Black women. According to the National Partnership for Women and Families, Black women earn about 61 cents for every dollar non-Hispanic white men earn. The takeaway here is that the gender wage gap has the largest absolute negative impact on the earnings of women of color.

The Impact of the Gender Wage Gap on Black Women and Black Communities

In original research I conducted using descriptive as well as regression analysis most of the most important factors that could contribute to wages/earnings differentials between Black women and non-Hispanic white men, such as educational attainment of years of work experience, have been taken into account, or, “controlled for,” which means that in my research I compare full-time working Black women and non-Hispanic white men with similar educational attainment, similar work experience, and many other similarities with regard to the skills they bring to the job. Thus, I am comparing “apples to apples.” I examine the earnings differences by occupation between Black women and non-Hispanic white men, and, with few exceptions, non-Hispanic white men earn considerably more than Black women in almost all 22 major occupational categories and almost all 77 minor occupational categories. For an individual Black woman who’s a worker, the gap ranges. It can be as low as $5,000 in certain low-wage occupations, or it can be as high as $50,000 to $75,000 in some high-wage occupations. More or less, on average, the gap in earnings between Black women and non-Hispanic white men ranges between $10,000 to $20,000 for your typical Black woman worker in the U.S. workforce. In the aggregate, I estimate that Black women workers in the U.S. “involuntarily forfeit” approximately $50 billion in wages/earnings due to the gender wage gap each year, a large and recurring loss to the Black community.

Causes of Large Differentials in Full-Time Annual Earnings between Black Women and White Men?

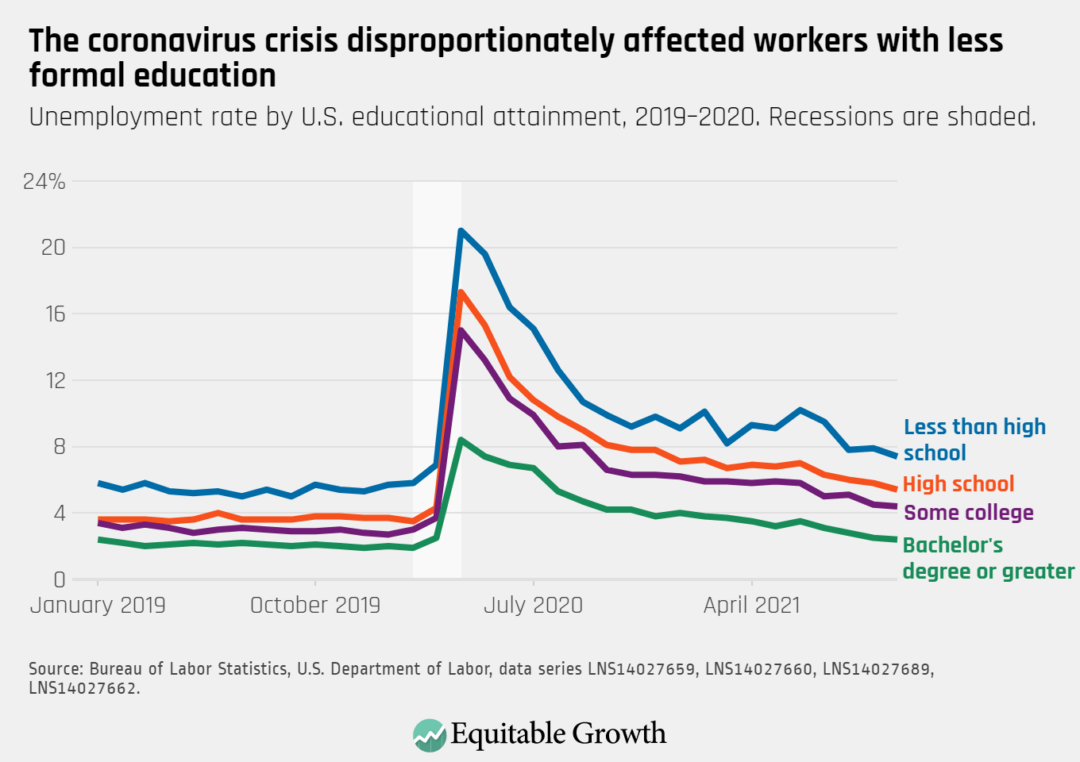

Several factors can contribute to the gender wage gap faced by all women, and by Black women in particular. Contributing factors to the gender wage gap that Black women face include their historically subordinate position in the American labor market, the role of networks, differences in college completion rates between Black and white Americans (there is still a large educational attainment gap between Blacks and whites—over 35% of non-Hispanic whites have a college degree compared to about 25% of Blacks), the use of prior earnings history in determining wages (in the 2018 Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals case Rizo versus Yovino, subsequently vacated by the U.S. Supreme Court on a technicality, the common practice of requesting previous salary histories from job applicants was found to be discriminatory against women), the lack of wages/earning transparency in the American workforce, and discrimination.

Black women, in line with women generally in the U.S. workforce, are crowded into low-wage occupations, in part due to the kinds of occupations that were historically open to African American women. This, of course, has an influence on the magnitude of wage gaps African American women face in the workforce. Conrad (2005) noted that, prior to the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, particularly Title VII of the Act which prohibited race and gender-based discrimination in employment, the occupation with the highest share of Black women in the U.S. (38 percent in 1960) was private household (i.e., domestic servants). Conrad pointed out that by 1980, the occupation with the highest share of Black women had changed from private household to clerical (also, see Albelda 1985 for more on this change). Indeed, in 2015, about one in five African American women worked in office and administrative support occupations, and an additional 17 percent worked in healthcare practitioner and healthcare support occupations, which includes jobs such as nurses, nursing assistants, medical records technicians, home health aides, and medical assistants.

It has been estimated that about half of jobs in the U.S. are filled through social contacts (Granovetter 1995). One potential explanation for this is such a process for filling jobs can be beneficial for, primarily, employers at no added human resource cost; Fernandez, Castilla, and Moore (2000) conceptualized the “richer pool” theory which indicates that, by tapping its employees for referrals for company vacancies, employers obtain a better and larger pool of candidates for job openings. Employers can reap other benefits from hiring individuals who were referred to the firm by incumbent employees, including referrals of candidates trusted by employees. Incumbents place their “reputation on the line,” provide other information about candidates not easily assessed during the hiring process, and help acclimate referral hires to their new work environment (Elliot 2001; Fernandez, Castilla and Moore 2000; Granovetter 2005). In addition, other research posits that African Americans tend to rely on formal routes in employment (Holzer 1987, Elliot 2001). Holzer (1987) argues that Blacks are more likely to rely on formal routes to employment because it is harder for ascriptive characteristics to play an outsize role in hiring, given the professionalization of the human resources occupation. Importantly, other researchers (Stainback 2008) have pointed out that networks can serve to maintain racially (or gender, for that matter) segregated labor markets since job information is shared through homogeneous networks, leading employers to draw from homogeneous pools. The point here is that, given the long-standing exclusions of all women and Black men from equal competition in the American labor market, white male networks in the workforce have an historical and potent reach. Presumably, not only is job vacancy information shared through homogenous white male networks, but also salary information.

Policy Approaches that Have Potential to Narrow the Gender Wage Gap for Black Women

The following policy approaches have the potential to narrow the wage gap faced by Black women in the U.S.:

- Passage of state and/or federal laws which prohibit employers from requesting previous salary histories from job applicants.

- Passage of state and/or federal laws requiring pay transparency in the private, for-profit sector; economist Marlene Kim (2015), the other economist providing testimony today, has found that in states where pay secrecy practices are banned the gender wage gap is lower among highly educated women.

- Revision of the “EEO-1 Form” to include compensation data. This form, required to be submitted regularly by employers, already reports the demographic and occupational makeup of most workers in the U.S., and this data is used by the EEOC to “support civil rights enforcement.” Under former President Obama an executive order implemented a revision to the form to include compensation data; this was jettisoned under former President Trump’s administration. I am calling for this revision to be re-implemented.

- The likelihood of acquiring student debt is a disincentive to attending college—making tuition free at community and public colleges throughout the U.S. would incentivize more Black women to complete college, raising this group’s median educational attainment level which will likely narrow their wage gap.

- Raise the federal minimum wage. The majority of minimum wage earners in the U.S. are women, and proportionally more Black women earn the minimum wage than Black men. Economist Marlene Kim has found a small but positive effect on the gender wage gap is likely to occur by raising the minimum wage.

Conclusion

It’s easy to attempt to scapegoat women in general for the wage gaps they endure by asserting that they, as a group, lack, for example, adequate negotiating skills. But it would be incorrect to do so. Research by Gerhart and Rynes (1991) as well as Laura Crothers et. al. (2010) shows that even when women engage in the same salary negotiating strategies as men their economic returns are lower. Research also shows that when Blacks attempt to assertively bargain fair salaries they are perceived as aggressive, and risk either losing employment offers or being offered lower salaries for violating employer’s expectations, when compared to their white male counterparts engaging in the same behavior (see Hernandez et. al. 2019).

The burden of shrinking the double gap lies primarily with employers who must recognize and acknowledge that they are underpaying Black women, writ large, and take measures to rectify this. But CEOs are not going to do this of their own volition, so we need our policy advocates, policymakers, and legislators to push corporate America in the right, and fair, direction.