Overview

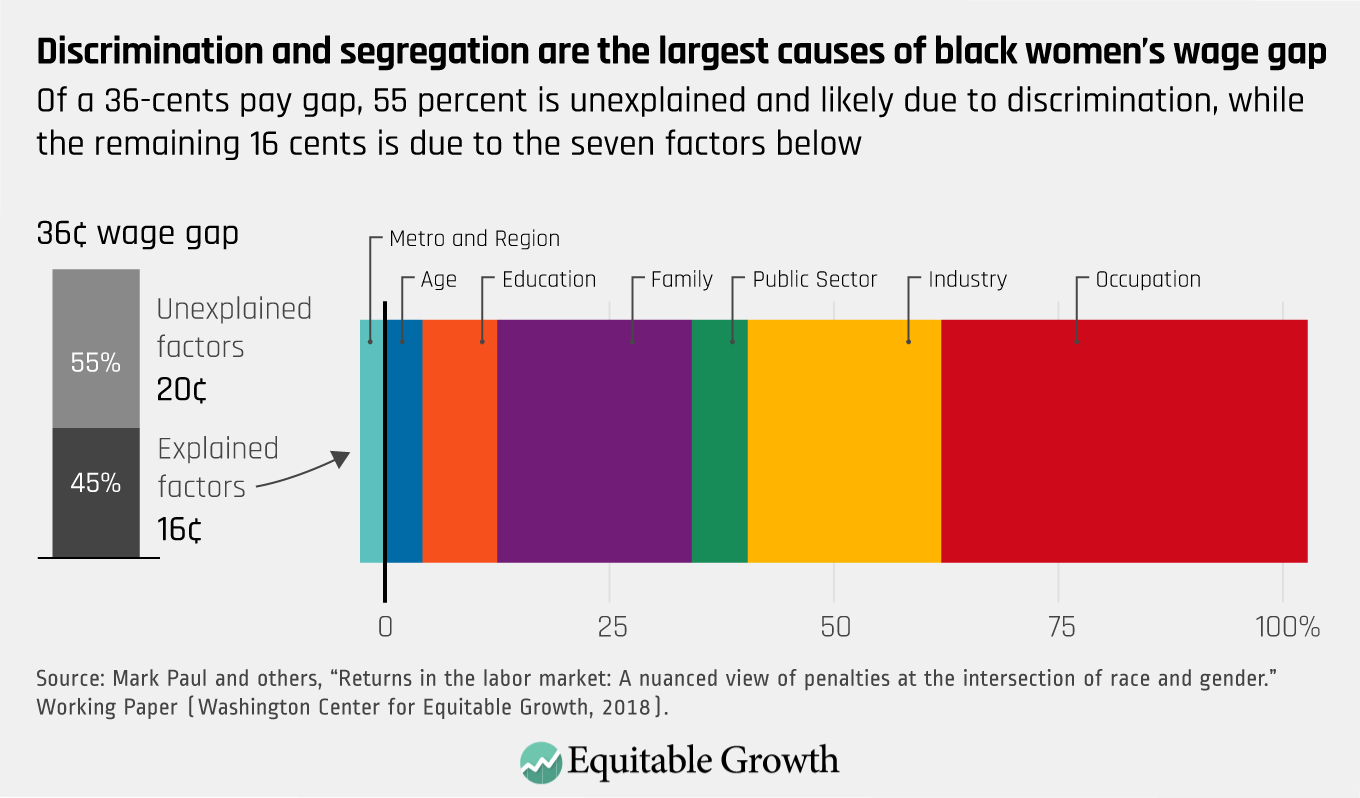

Earlier this month, Equitable Growth released a working paper on the wage gap faced by African American women to coincide with Black Women’s Equal Pay Day, the date in 2018 when black women in the United States must work, on average, to make as much as white men made in 2017 alone. The paper, authored by economists Mark Paul of the New College of Florida, Darrick Hamilton of the New School, and William Darity Jr. and Khaing Zaw of Duke University, calculates the wage gap for black women compared to white men and breaks down the different factors contributing to this persistent gap.

Download File

082818-african-american-women-paygap

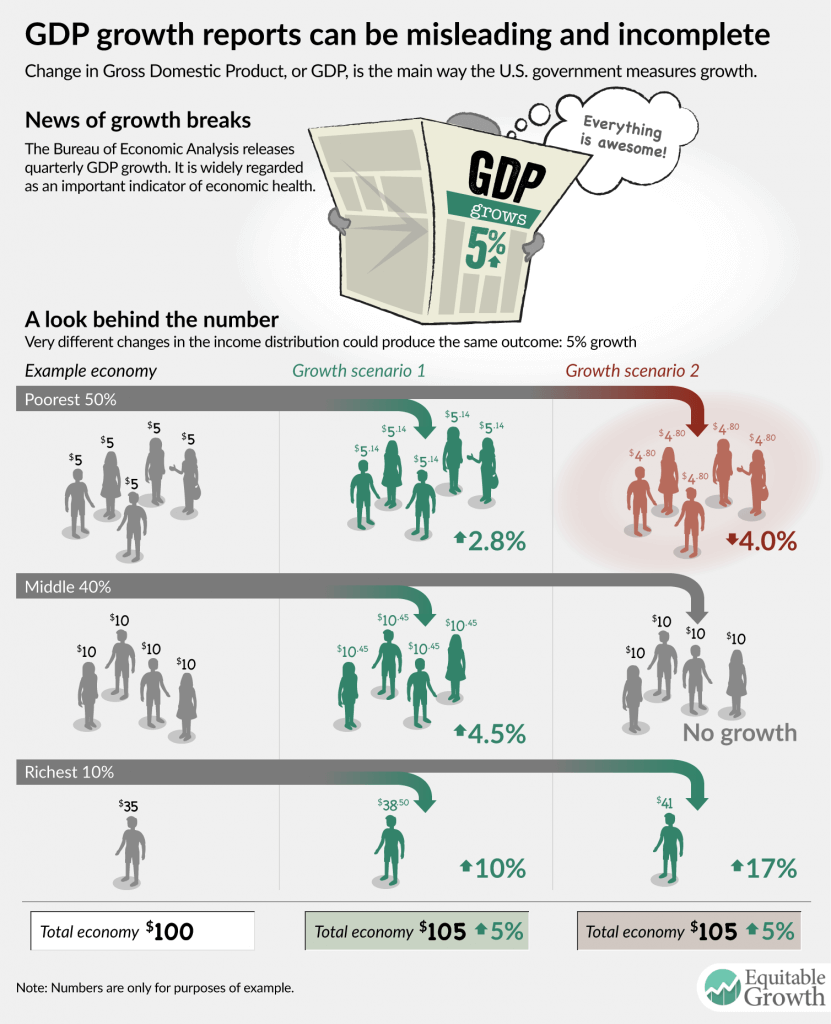

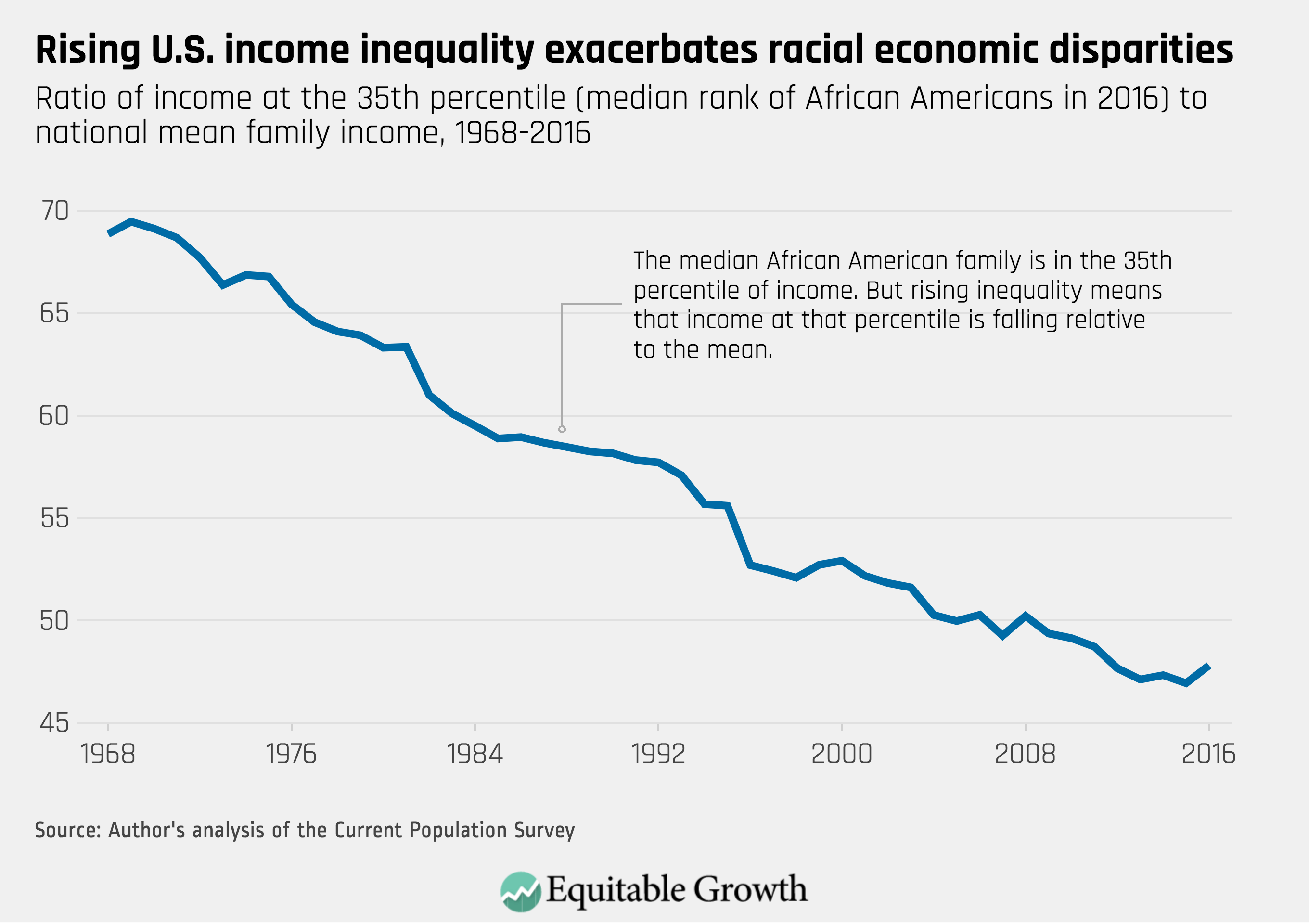

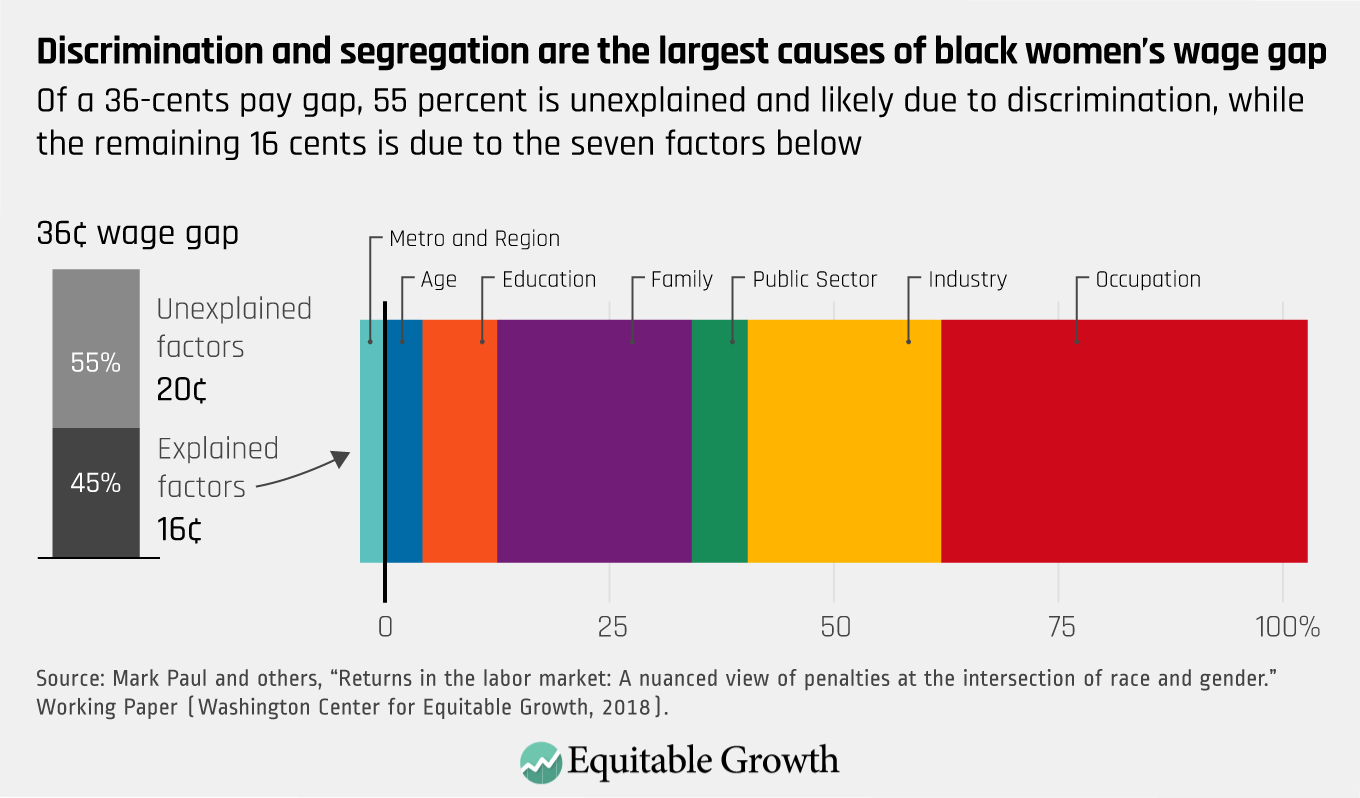

Using a wage decomposition strategy, the authors quantify a wage gap for black women of 36 percent (36 cents for every dollar earned by a white man), and they also determine that 55.5 percent of this 36-cent gap (20 cents for every dollar earned by a white man) is not explained by human capital variables, including age, education, family structure, occupation, or industry. This unexplained wage gap is often interpreted by economists as the closest approximation of genuine discrimination. Of the observed variables, however, racial and gender differences in industry and occupation—collectively referred to as workplace segregation—explain by far the largest portion of the gap (28 percent, or 10 cents for every dollar earned by a white man). The authors emphasize that these differences “themselves may result from discriminatory practices.”

Consistent with this finding, trends in workplace segregation in recent decades and numerous empirical studies investigating its causes and effects provide strong evidence for the discriminatory nature of the workplace segregation faced by African American women. In fact, workplace segregation is not efficient, but instead profoundly distortionary—dampening black women’s wages and weakening aggregate growth. This issue brief details the trends in workplace segregation over the past eight decades, the channels through which segregation contributes to workplace discrimination, and the continuing causes of this persistent discrimination.

Trends in workplace segregation of black women: 1940–present

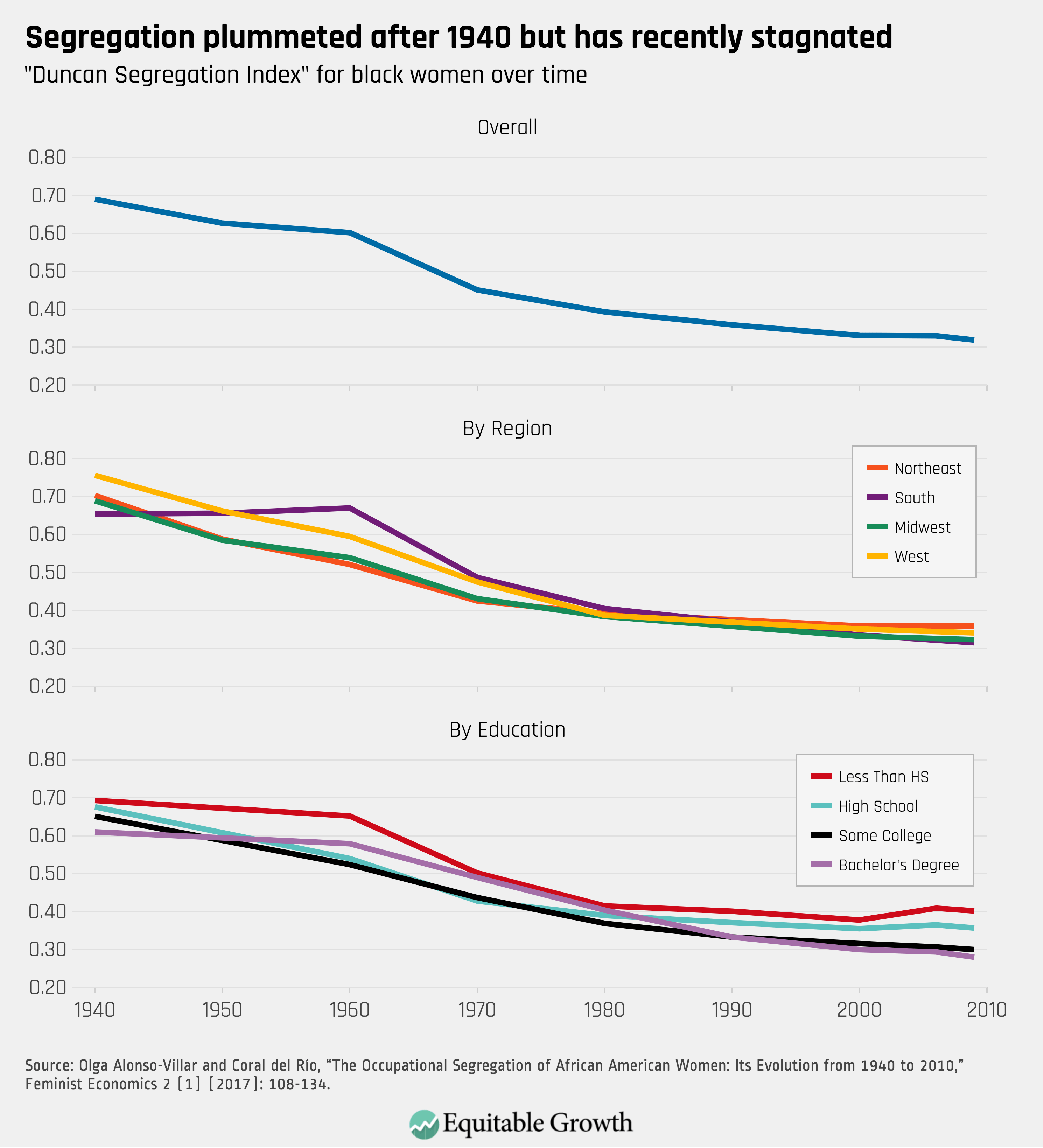

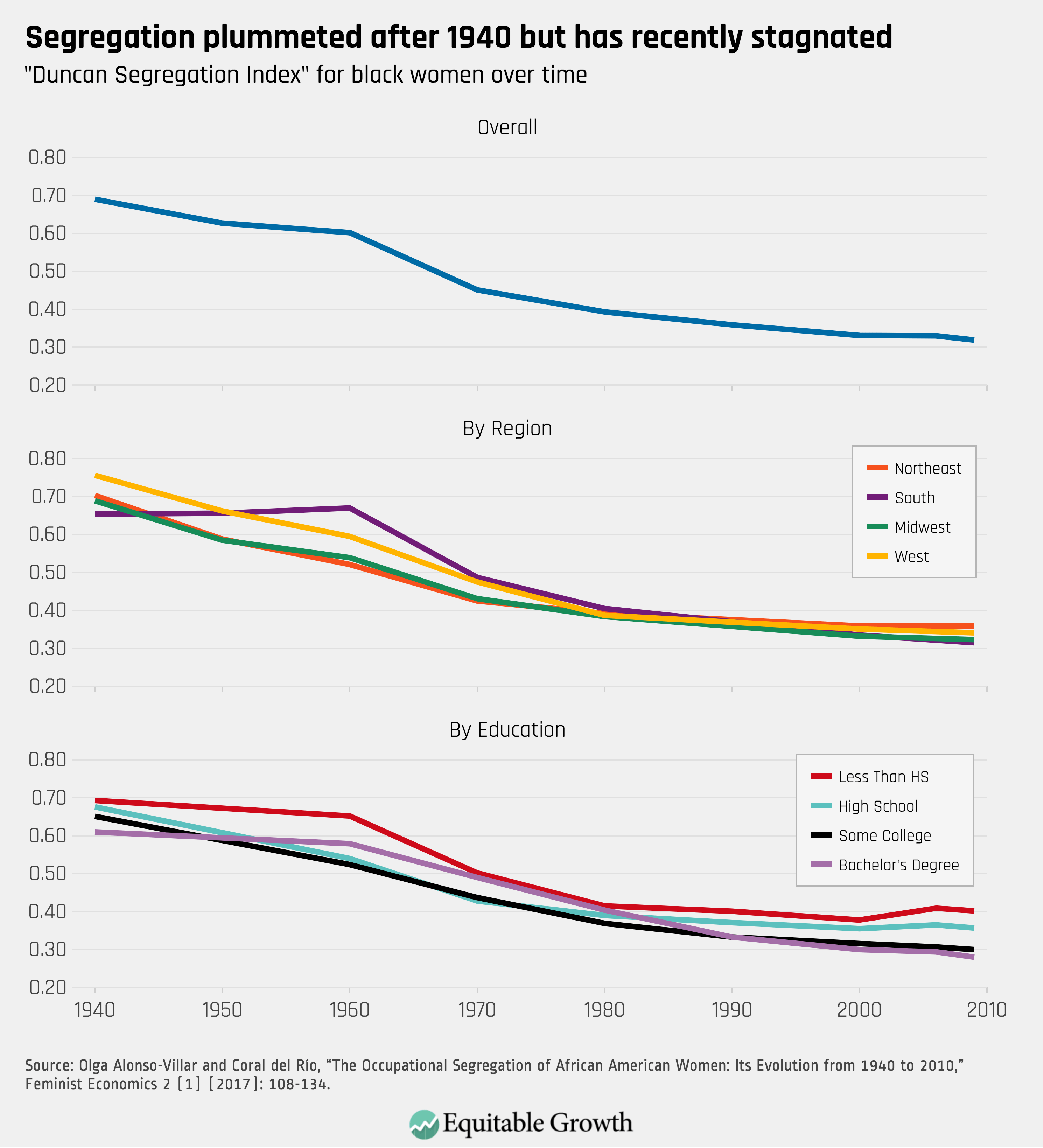

Olga Alonso-Villar and Coral del Río, two professors of economics at the University of Vigo in Galicia, Spain, have conducted extensive quantitative research on occupational segregation of black women, along with other racial and ethnic groups by gender, in the United States. Using the segregation index data generated by Alonso-Villar and del Río, changes in segregation levels for black women since 1940 in the aggregate, as well as by region and education, can be detailed. The index they construct represents the fraction of black women who would need to change jobs in order for their occupational distribution to be consistent with the average occupational distribution of all workers in the U.S. economy. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Over the course of this period, the aggregate occupational segregation of black women was reduced by more than half—from an index of 69 percent in 1942 to 32 percent in 2008–2010. Currently, 32 percent of African American women would thus have to change jobs in order to reflect the general distribution of workers among jobs in the economy. In a separate paper, Alonso-Villar and del Río calculate that this level of occupational segregation faced by black women is 38 percent greater than the segregation affecting black men and 43 percent greater than the segregation affecting white women.

As explained in more detail below, Alonso-Villar and del Río break down segregation trends for three 20-year intervals and disaggregate the respective effects of social movements and technological change in the multidecade decline in workplace segregation for black women. The authors define these social-movement effects as changes in the specific distribution of black women across occupations, likely as a result of changes in social norms. Technology effects are changes in the distribution of all workers across occupations due to structural changes in the economy as a whole such as the rapid mechanization of the agricultural sector in the post-World War II era.

Between 1940 and 1960, technological changes and the ongoing Great Migration of African Americans into the Northern and Western regions of the country helped facilitate black women’s moves from jobs often as farm laborers and domestic workers to growing and higher-paying white-female-dominated occupations in health care, clerical work, and other service sectors outside the South. The subsequent passing of civil rights protections and federal enforcement of affirmative action between 1960 and 1980 brought about an even sharper national decline in segregation—this time including the South—as black women further increased their representation in clerical occupations and also gained growing access to various management, professional, and technical occupations, which had formerly been dominated by white men.

Beginning in the 1980s through 2000, the pace of desegregation slowed dramatically as a result of declining civil rights enforcement and a judiciary increasingly hostile to discrimination claims. While African American women dramatically boosted their average levels of education and increased their numbers in managerial and professional occupations, many administrative support and service occupations came to be characterized by an overrepresentation of black women. For many black women with limited resources and professional connections, these administrative and service occupations thus became “the highest rungs in the [job] ladder,” explain Alonso-Villar and del Río. Since 2000, workplace segregation for black women at all levels of education has essentially stagnated, as was recently pointed out by economist Valerie Wilson and her co-author Madison Matthews at the Economic Policy Institute.

While black women remain underrepresented in entry- and middle-level positions across occupations and at all levels of education, disparities at the top are the most striking. A recent report by Lean In and McKinsey & Co., based on a survey of 222 companies employing more than 12 million people, documents that women of color as a group (including black, Latina, Asian American, Native American, and mixed race women) constitute only 3 percent of so-called C-suite executives, 6 percent of vice presidents, and 11 percent of managers. Likewise, using U.S. Census Bureau data, Ph.D. candidate in sociology William Scarborough of the University of Illinois at Chicago calculates that black women hold only 4 percent of all manager positions in the United States. As explained in more detail below, these discrepancies reflect the cumulative effect of discriminatory norms, policies, and behaviors throughout the corporate managerial pipeline.

The contribution of workplace segregation to the wage gap for black women

Workplace segregation is seriously damaging for black women’s wages because it concentrates them in lower-paying occupations, on average, compared to white men and other groups. As discussed above, the authors of Equitable Growth’s recent working paper—Paul, Hamilton, Darity, and Zaw—separate out the effects of various observable variables (including occupation and industry) on the wage gap faced by black women vis-à-vis white men, enabling them to calculate the relative size of the explained and unexplained gaps, as well as the respective contributions of relevant human capital and demographic variables to the former. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Quantitative research demonstrates that pervasive wage penalties based on occupational racial and gender compositions are not rooted in productivity differences, but rather in social norms and stereotypes. Controlling for a large number of variables in local labor markets, sociologists Matt Huffman of the University of California, Irvine and Philip N. Cohen of the University of Maryland find that race- and gender-based devaluation of jobs associated with particular demographic groups are widespread—with occupational wage penalties largest in the most segregated labor markets. This reality has led many economists, including the former president of Bennett College, Julianne Malveaux, to advocate for a comparable-worth approach to pay equity, mandating that African American women receive equal pay for jobs of equal value.

Wage penalties depress black women’s wages across occupations and at all skill levels. While Alonso-Villar and del Río demonstrate that segregation levels for black women decrease to some extent with education, they find relatively comparable wage penalties for them no matter their educational backgrounds. As organizer and writer Alicia Garza has interrogated and sociologists Paula England of New York University and Michelle Budig of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, along with economist Nancy Folbre of UMass Amherst, have reported, African American women are particularly disadvantaged by the wage penalty for care work given their overrepresentation in the field and the substantial wage devaluation affecting care workers. Beyond their concentration in the lowest-paying occupations, black women also are overrepresented in many middle-income jobs that pay less than male-dominated jobs with similar skill requirements.

In addition to these clear effects on the “explained” wage gap, there is evidence from behavioral economics and social psychology that workplace segregation may also worsen the “unexplained” gap by fostering environments where harassment and discrimination are widespread. Indeed, there is a large body of evidence in the social sciences substantiating that minority groups are at the highest risk of discrimination and harassment in work environments where they are heavily underrepresented.

A highly segregated workplace culture has been empirically demonstrated to substantially lower the wages of black women—along with those of black men, LGBTQ workers, women of all races and ethnicities, and other underrepresented groups—in a variety of ways. It can lead to pay discrimination against black women due to the prevalence of discriminatory stereotypes and norms. It can result in work sabotage whereby black women are undermined in their efforts to fulfill their job responsibilities and lose out on the chance to take on the most highly remunerated tasks. It can cut them off from social networks that provide access to information necessary to maximize earnings potential. And it can push them to take jobs in lower-paying firms even if they remain in the same occupation.

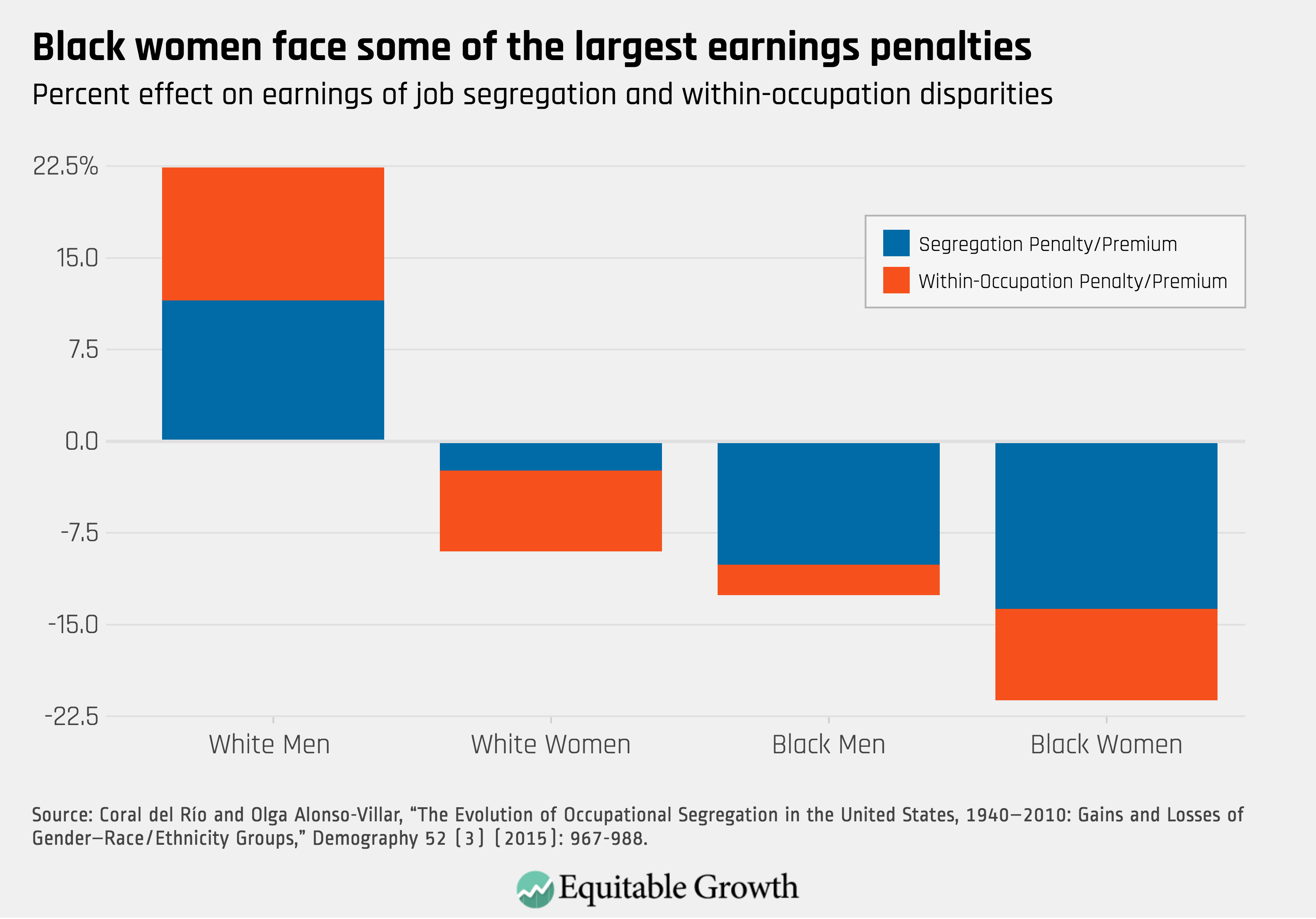

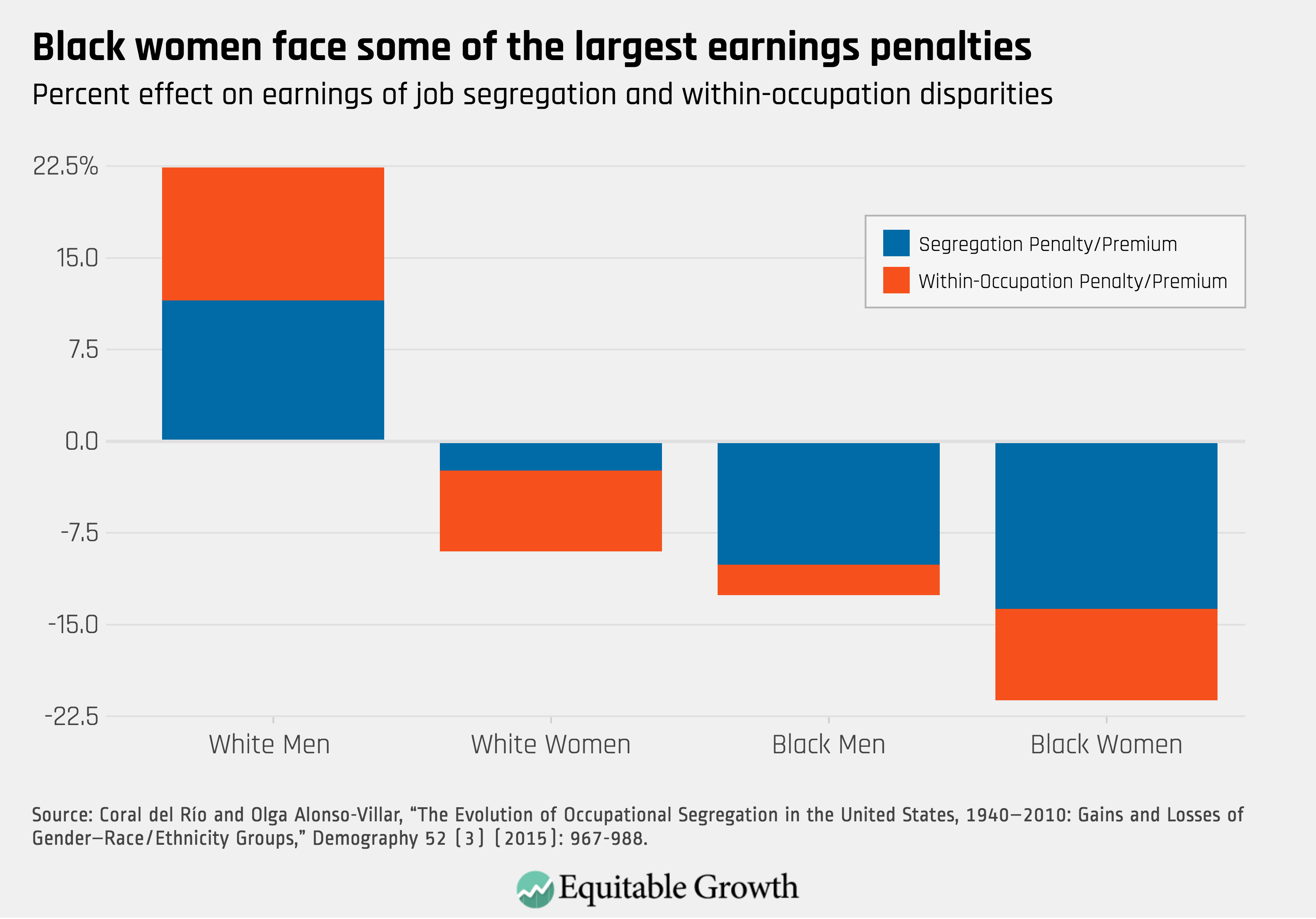

Comparing average earnings levels by demographic group vis-à-vis the average level for all workers in the economy, Alonso-Villar and del Río calculate the size of the penalty/premium for various gender groups by ethnicity and race, as well as the relative contributions of the groups’ occupational segregation to the wage gap. They find that black women face larger earnings penalties than white women and black men—both in terms of segregation and in terms of within-occupation inequalities, although the combined effects on earnings relative to the economy’s average are negative and substantial for all three groups. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

This evidence makes clear that black women face significant wage discrimination even when working in the same jobs as white men. On the other hand, the research below explains how the jobs in which black women end up are often determined by discrimination as well.

Discriminatory causes of workplace segregation of black women

Workplace segregation is traditionally understood to be the result of the sorting of workers in the labor market on the basis of skills, preferences, and ambitions, yet recent empirical research demonstrates that differences in workers’ skills and interests are too small to explain the high levels of race- and gender-based segregation in the contemporary workforce. Indeed, while there are some average differences in certain measures of academic performance among adolescents and young adults, the performance distributions by gender and race are heavily overlapping and insufficient to explain the large extent of persistent segregation—as neuroscientist Lise Eliot of Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine has detailed extensively. On top of various studies questioning the reliability of test scores in measuring academic and earnings potential, there also is evidence indicating that documented academic disparities probably reflect the cumulative effects of discrimination and inequality. Rigorous empirical studies substantiate this claim, finding nonexistent or negligible racial and gender gaps in cognitive skills among the youngest children.

Instead of adhering to the traditional human capital explanation of sorting based on skills and interests, contemporary economic and legal scholars argue that labor market preferences—both among groups that face discrimination and among those that perpetrate it—are largely determined by education, workplace, and other institutions that exist in the status quo. As I explained in a previous issue brief for Equitable Growth on the efficiency case for workplace integration, economists propose several theories to explain why such institutions continue to limit black women’s labor market opportunities. In the stratification economics model proposed by Professor Darity or in the identity economics model developed by economists George Akerlof of Georgetown University and Rachel Kranton of Duke University, economically advantaged groups such as white men in the United States support institutions that perpetuate segregation in order to maximize their own socioeconomic power or sense of identity.

Another explanation is offered by Harvard economist Claudia Goldin. Pointing instead to the informational distortions created by occupational segregation in the status quo, she posits that members of society may discriminate based on stereotypes they erroneously infer about the skills of black women and other disadvantaged groups from their current underrepresentation in the highest-paying occupations.

Consistent with all of these frameworks, one major driver of occupational segregation is the racial and ethnic disparity in access to resources, which hurts children’s educational outcomes and thus their long-term labor market opportunities. In their study on intergenerational mobility for different racial/gender groups in the United States, economists Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren of Harvard University and Maggie Jones and Sonya Porter of the U.S. Census Bureau illustrate that much of the occupational segregation faced by black women can be explained by controlling for parents’ income. These results prove that for many black women, it is access to resources as children rather than differences in preferences or abilities that determines their limited occupational options as adults. Importantly, however, Chetty and his co-authors find persistent race- and gender-based segregation among the children of parents in the eighth income decile—those making between approximately $90,000 and $115,000 as a household—pointing to the important role of discrimination even among children in upper-income families.

Together with resource disparities, recent empirical studies chronicle several ways in which family members, schools, and society at large can impose limits on black women’s labor market opportunities. To start, children’s career aspirations are fundamentally influenced by their parents’ occupations, as well as widespread social views on the appropriate occupational choices for various groups. In elementary and high school, students’ interests are also determined based on the occupations of the role models and social networks to which they are exposed. Later on, in college, research by psychologist Colleen Ganley of Florida State University and her co-authors finds that perceived levels of discrimination—as opposed to interests in particular fields—are the primary determinant explaining women’s underrepresentation in STEM, or science, technology, engineering, and math, and certain non-STEM majors such as economics, philosophy, and, to a lesser extent, business.

Educational institutions can also foster discriminatory norms and beliefs about black girls and women among economically advantaged groups. Despite progress since the mid-20th century, stereotypes about and biased attitudes toward black women remain widespread in contemporary media messages. Counteracting these harmful tropes requires conscious efforts to expose children to a diverse array of classmates and counter-stereotypical role models. Unfortunately, the contemporary reality of widespread race- and income-based school segregation does the exact opposite—keeping African American girls out of many of the highest performing white-dominated schools and thus allowing pernicious stereotypes and prejudices to thrive in these largely homogenous student bodies. Recent efforts to improve outcomes for black boys by creating all-male schools have likewise been criticized by black feminist scholars for excluding black girls from these enrichment opportunities, particularly given the dearth of evidence justifying segregated educational programs.

In addition to the role of institutions in shaping labor market preferences at a young age, research demonstrates that workplace structures—and the experiences they generate—also have a profound impact on occupational segregation. In a recent article, legal scholar Vicki Schultz of Yale Law School leverages legal and social science evidence to argue that sex segregation and unchecked “subjective authority” (i.e., mangers’ substantial power to determine their employees’ career outcomes with limited standards and accountability) work in concert to create climates of discrimination and harassment, keeping women, especially queer women and women of color, out of white-male-dominated fields. In many historically white male workplaces, including financial, management, and STEM professions, negative experiences of discrimination have been empirically documented to begin early on in a worker’s tenure, and they accumulate as black women and members of other minority groups move through their careers. Indeed, the experiences of harassment, work sabotage, and network closure discussed above do not only result in wage discrimination in highly segregated occupations; they also push black women out of white-male-dominated fields into lower-paying occupations.

As legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw of Columbia University and the University of California, Los Angeles and sociologist Enobong Branch of the University of Massachusetts Amherst (among other researchers) have theorized and empirically documented, black women are uniquely disadvantaged as they face the discriminatory stereotypes, resource disparities, and other inequalities affecting African Americans and women in general—as well as those affecting black women in particular. This reality means that economic penalties imposed on black women are not necessarily additive and are instead often greater than the mere aggregation of race- and gender-based effects.

Economist Cecilia Conrad, who currently serves as the managing director of the MacArthur Fellows Program of the MacArthur Foundation, has argued that the unique complex of stereotypes and inequalities faced by black women is a central explanation for the lack of effective public policy targeted at increasing their incomes and economic security. Along with sociologist Rose M. Brewer of the University of Minnesota and economist Mary C. King of Portland State University, Conrad calls for a more nuanced and intersectional analysis of the interplay between race, gender, and class in economics, as well as greater empirical focus on the specific challenges faced by black women.

Conclusion

While the persistence of U.S. workplace segregation in the 21st century is discouraging, particularly given its large negative effects on black women’s wages, the good news is that historical and contemporary research shows that segregation can be deeply malleable. After all, the trends over the past eight decades described by Alonso-Villar and del Río did not take place in a vacuum but were instead the result of massive social movements and subsequent policy and legal reforms that pressured firms to hire more black women along with members of other economically disenfranchised groups. Empirical evidence also demonstrates that occupational integration can both dramatically increase black women’s wages—accounting for 56 percent of black women’s earnings growth from 1960 to 2010—and decrease the prevalence of the discriminatory stereotypes and norms that are both causes and effects of workplace segregation.

Beyond these encouraging implications for the wages of black women and the economic security of their families, there is growing evidence that desegregating the workplace also would boost human capital skills, productivity, innovation, and growth. In terms of human capital, Chetty and his co-authors find that controlling for parents’ income, black women have higher rates of college attendance compared to white men, demonstrating the large benefits of removing barriers to their economic advancement. Furthermore, there is burgeoning evidence that increasing racial and gender diversity at all levels strengthens productivity, innovation, and financial performance in firms across industries.

Combined, these microeconomic improvements can have massive aggregate effects. Economists Chang-Tai Hsieh and Erik Hurst of the University of Chicago and Charles I. Jones and Peter J. Klenow of Stanford University estimate that occupational integration by race and gender was responsible for one-quarter of the growth in aggregate output per worker since 1960. These results make clear that workplace segregation of black women does not just restrict their opportunities; it also holds back the broader U.S. economy.