Race and gender disparities in wages are a relentless and troubling feature of U.S. labor markets. Economists have investigated the gender wage gap and racial wage gap for more than half a century, yet most empirical research still considers these two types of wage gaps in relative isolation, treating race and gender wage gaps separately. Examining these two wage gaps through the lens of intersectional theory, however, enables researchers to understand how workers with multiple socially salient identities such as race and gender are affected in ways that are qualitatively different from the mere sum of the effects of each identity taken separately on outcomes in U.S. labor markets.

Intriguingly, the intersectionality of race and gender and the comparative advantage or disadvantage for individuals holding multiple identities are topics that are increasingly more common in the press. A recent article in the Washington Post on the gender pay gap observed that “women of color get hit twice: they suffer the effects of the gender wage gap plus those of the racial wage gap.” Others emphasize how focusing on one socially salient identity such as gender alone overlooks the importance of holding multiple identities. In The Atlantic, for example, Adia Harvey Wingfield challenges the “now famous” statistic that women make 79 cents on the dollar vis-á-vis men, arguing that “it obscures even wider gaps faced by women of color.” And a recent op-ed in the New York Times acknowledges that penalties or privileges associated with certain identities depend on the bundle of identities that the individual holds, noting that “the racial pay gap is narrower among women” in comparison to men.

A new working paper made possible with the generous support of the Nathan Cummings Foundation, “Returns in the Labor Market: A Nuanced View of Penalties at the Intersection of Race and Gender,” seeks to quantify some of the insights from intersectional theory and critical race theory in order to more thoroughly examine what many in the press already understand intuitively. Specifically, we investigate whether the magnitude of the gender and racial wage gaps varies across group identity. Do blacks and whites face different gender wage gaps? Do men and women face different racial wage gaps? We then present evidence that holding multiple identities cannot readily be disaggregated in an additive fashion, but rather the penalties associated with holding a combination of two or more socially marginalized identities interact in more quantitatively nuanced ways.

Our work provides a robust illustration of why economists should take intersectionality theory seriously in their analyses of labor market discrimination moving forward. We seek to deepen the understanding of how the possession of one socially salient identity such as being a woman or being black may oversimplify the effects of the complex of social identities that interact in ways which researchers still need to identify.

Our first finding: Wage gaps vary significantly across groups

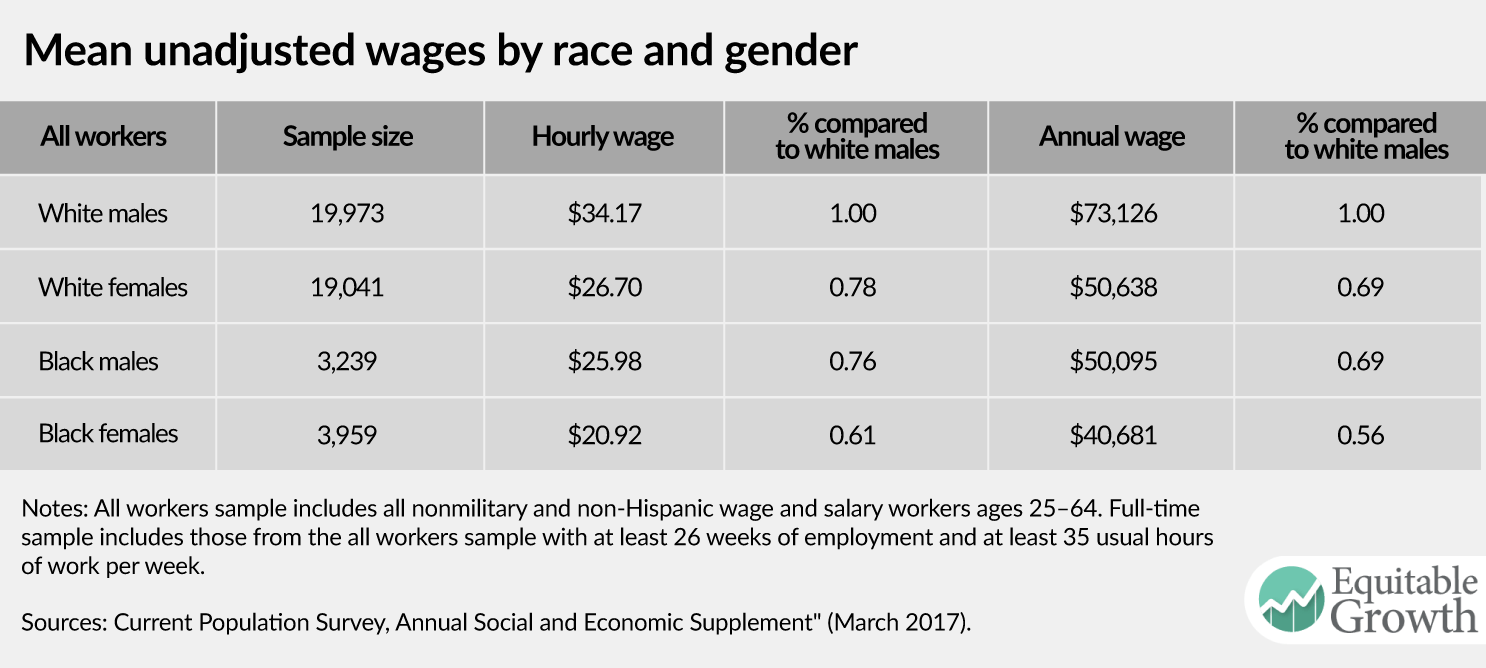

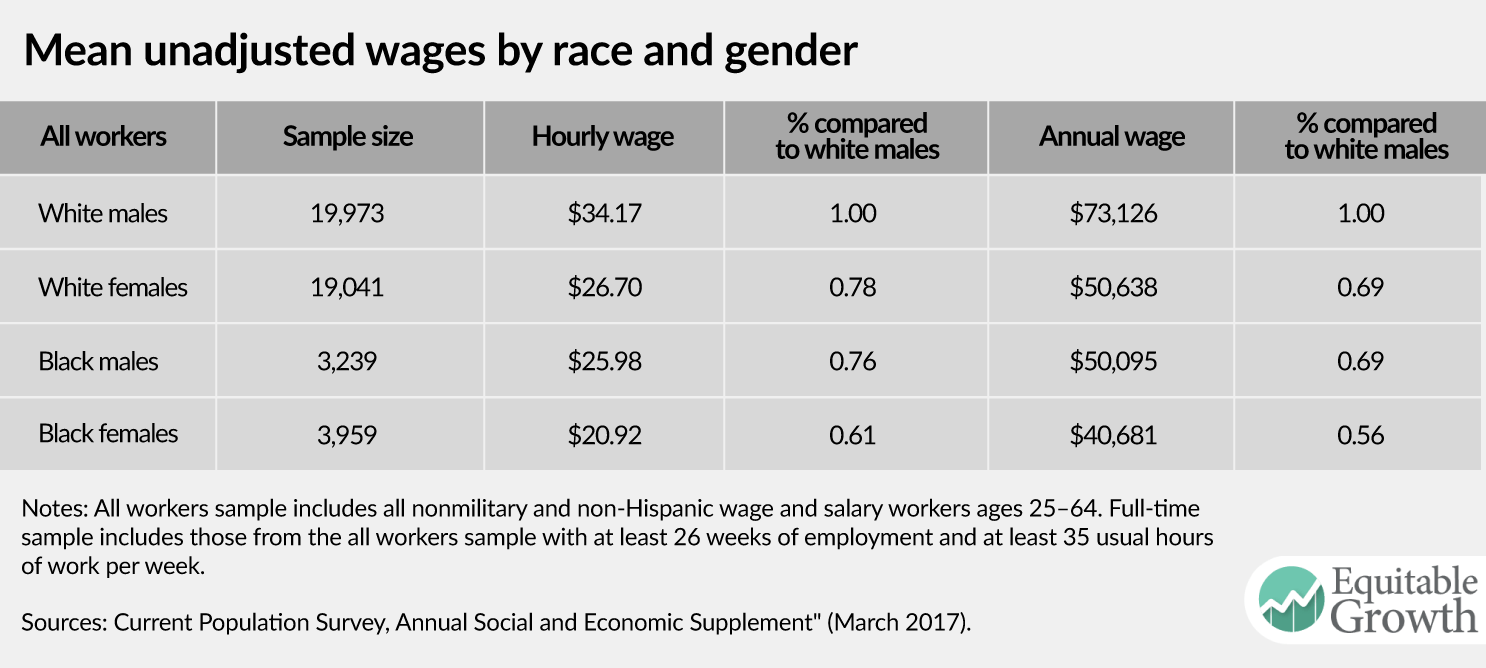

There are substantial hourly wages and annual salary gaps (henceforth wages) across race and gender. As expected, our research finds that white men attain the highest average wages. We then observe that white women receive the highest wages after white men, with hourly wages that are 78 percent of those received by white men. This gender wage gap is exacerbated when we analyze annual wages as opposed to hourly wages, with white women receiving only 69 percent of the annual wages received by white men. Our results are confined to workers that are employed for pay, and thus the more pronounced differences in annual wages may reflect greater hours worked and fewer bouts of unemployment for white men.

The wage gap between black and white men is similar in magnitude to the gap between white women and white men. Black men receive just 76 cents on the dollar in hourly wages compared to white men. Annual wage gaps are even larger. This may be due to a number of factors, including the fact that black men are more likely to experience incarceration and unemployment and are more likely to be working part-time during a given year.

Black women endure the largest wage gap observed, as they receive wages that are just 61 percent, on average, of those received by white men. In terms of the mean annual wage gap, black women receive just 56 percent of what white men receive. (See Table 1 for the summary statistics for mean wages in 2016 for our sample, which consists of black and white workers.)

Table 1

Our second finding: There is no single “gender” or “race” penalty

Individuals who hold multiple socially salient identities face different race or gender penalties once we control for productivity-linked traits, as well as other variables that may contribute to differences in wages. By analyzing how gender or race relate to wages across different groups, we are able to identify, for instance, that black women relative to black men and white women relative to white men face substantially different wage disparities associated with their gender.

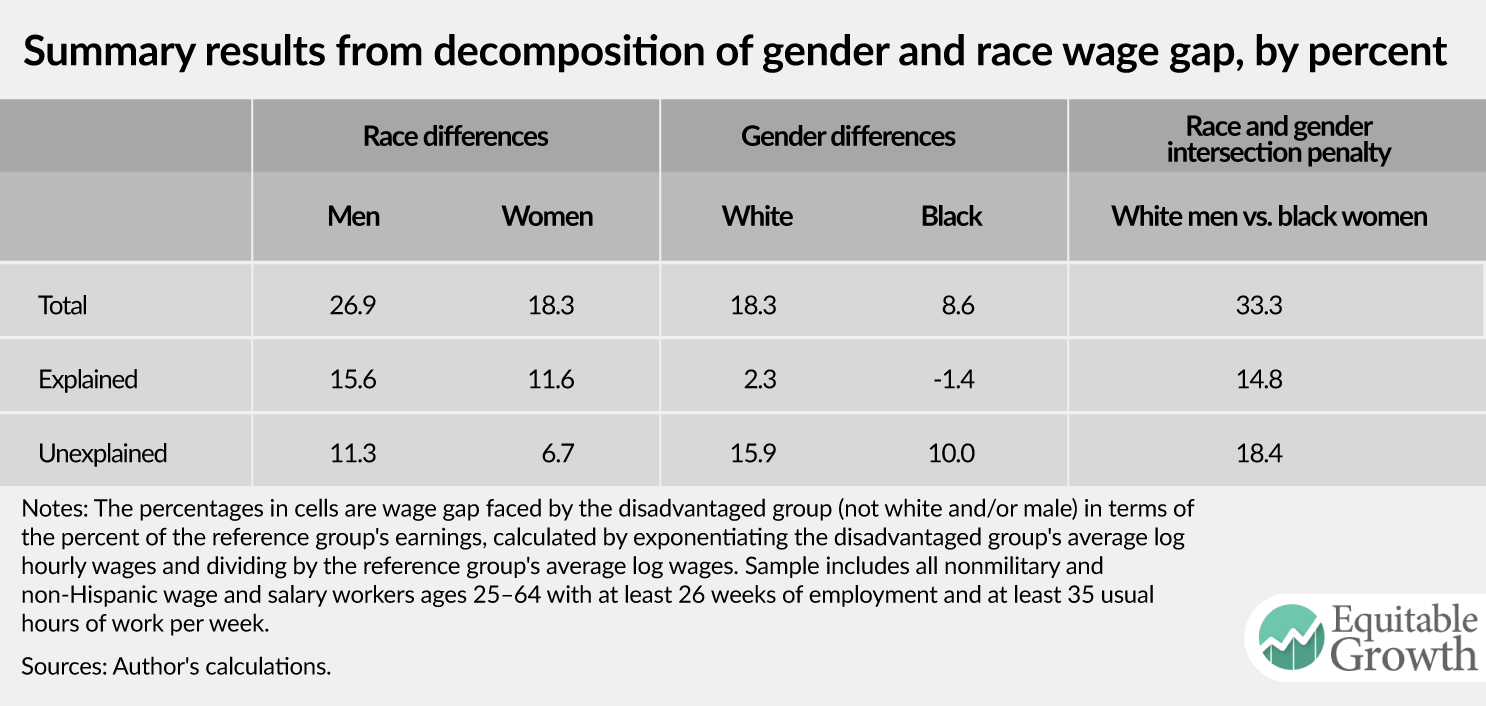

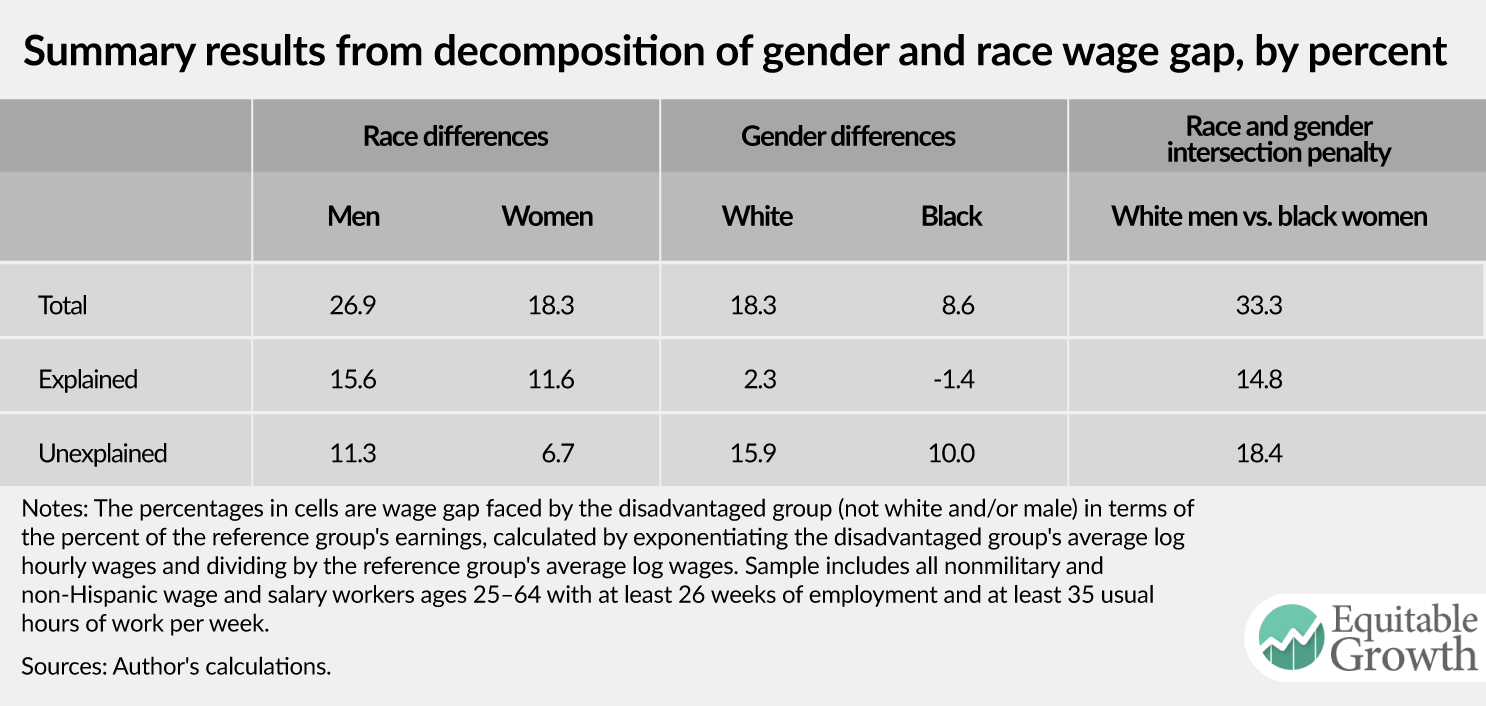

Our findings show that black men earn 26.9 percent lower wages than comparable white men. The use of controls in our model provides us with the statistical basis for estimating the adjusted wage gap that isolates differences in wages due to labor market characteristics from differences in which labor market characteristics translate into wages due to an individual’s race. The controls (labor market characteristics) reduce this pay gap, explaining 15.6 percent—more than half of the gap—yet 11.3 percent of the gap remains unexplained. This unexplained portion is typically interpreted as statistical evidence for race (or gender) discrimination. As we can see, black men face a larger race pay gap than black women, largely because the results compare black women to white women, whose wages are at least somewhat suppressed, vis-à-vis white men, as a result of their gender.

Second, we see that gender pay differences also differ by race, with white women facing a larger gender pay gap than black women, in this case, because black women are compared to black men, whose wages are suppressed, vis-à-vis white men. In sum, particularly for black women, the magnitude of the penalty for any particular identity is conditional on the combination of other identities the individual possesses—there is no single “gender” or “race” penalty. (Our findings are highlighted in Table 2, where we display differences associated with the race penalty for men and women.)

Table 2

Finally, we quantify and frame some aspects of intersectionality. While critical race theory and the national media often have discussed a presumed “double burden” faced by individuals holding two socially salient disadvantaged identities, this study provides important analytical and empirical insight about the actual magnitude of the burden economywide for black women.

Using white men as the reference group, we examine the wage penalties of black women, a group that holds two socially marginalized identities, to determine if this disadvantage is above and beyond the penalties associated with simply adding isolated penalties ascribed to black women due to their gender relative to black men and their race relative to white women. The wage gap between these two groups amounts to black women receiving 64 cents on the dollar compared to white men. Further, black women are penalized approximately 20 cents on the dollar due to discrimination in this comparison. We find that the wage gap between black women and white men is larger than the sum of the two individual penalties. This confirms that to truly understand the labor market experience for black women, one cannot simply examine racial and gender discrimination in isolation.

Economists typically fail to fully explore or explain the persistence of discrimination in U.S. labor markets. While standard economic models assume the competition will eliminate discrimination, making it merely a temporary phenomenon, the real world has proven that discrimination is resilient and omnipresent. Our paper demonstrates that in addition to discrimination based solely on a singular identity such as race or gender, some groups face compounded discriminatory penalties based on the intersection of their identities. The finding highlights the critical role intersectionality should play in the economic analysis of discrimination.

—Mark Paul is an assistant professor of economics at New College of Florida and a fellow at the Roosevelt Institute. Darrick Hamilton is a professor of economics and urban policy at the Milano School of International Affairs, Management and Urban Policy and Department of Economics at the New School for Social Research, is director of the Doctoral Program in Public and Urban Policy at The New School, and is co-associate director of the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity at Duke University. William Darity Jr. is the Samuel DuBois Cook Professor of Public Policy, African and African-American Studies and Economics and the director of the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity at Duke University.