Brad DeLong: Worthy reads on equitable growth, June 29-July 5, 2018

Worthy reads on Equitable Growth:

- Austin Clemens writes in “Realizing the promise of place-based economics requires more and better data from across the United States” that “the recent pivot by researchers and policymakers to studying the economics of place is a welcome development. But this research is especially data intensive. If policymakers are serious about the promise of place-based policymaking, then they also need to be serious about collecting good data and making it accessible to researchers.”

- Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Maggie R. Jones, and Sonya R. Porter note in “Race and economic opportunity in the United States” that “racial disparities persist across generations in the US. … Black men have much lower chances of climbing the income ladder than white men even if they grow up on the same block. In contrast, black and white women have similar rates of mobility.”

- Heather Boushey and Greg Leiserson in The American Prospect write in “Worsening Inequality” that “the Tax Act worsens inequality both in the tax changes and in the program cuts used to address the resulting deficit.”

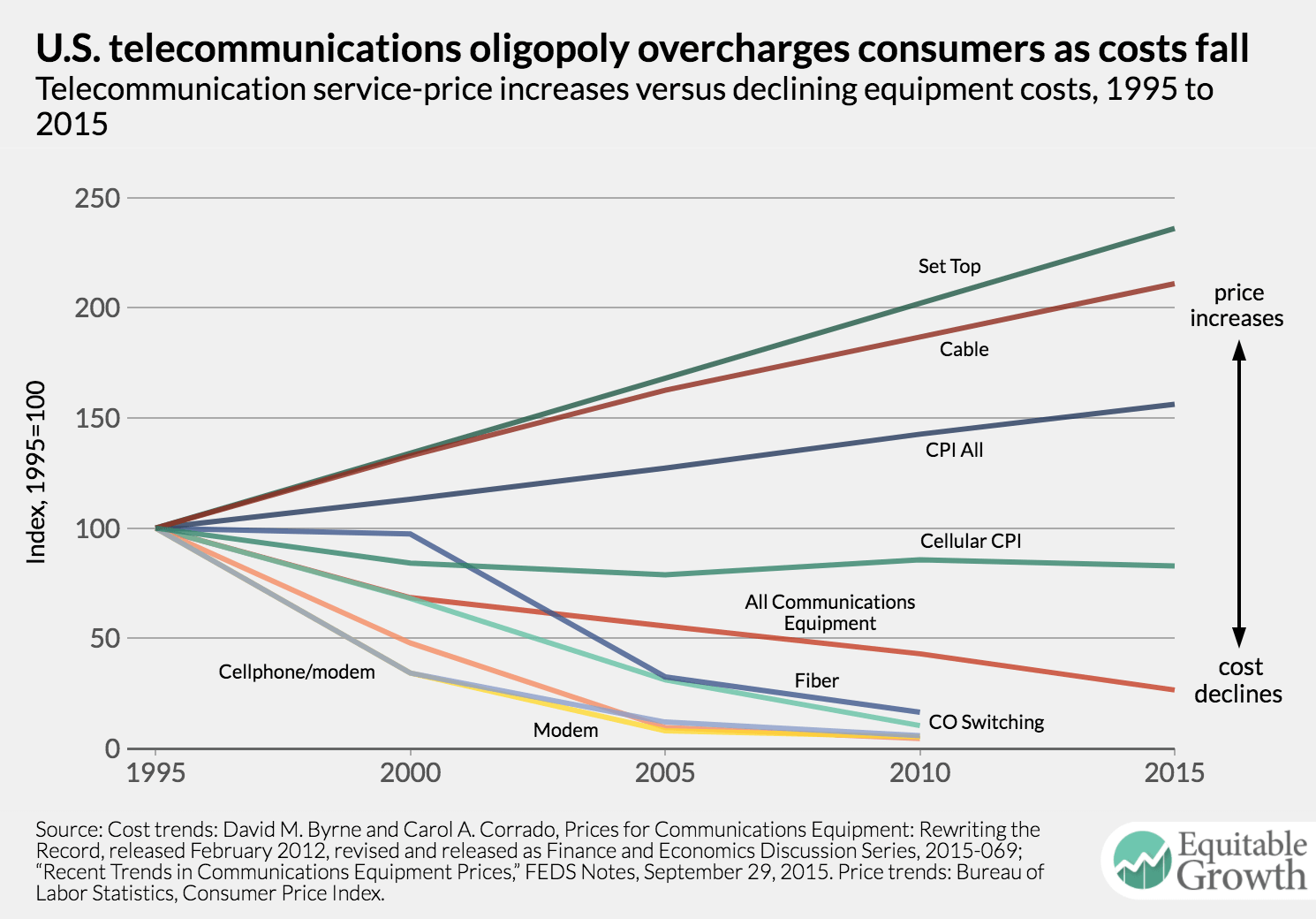

- Antitrust experts Gene Kimmelman and Mark Cooper last year produced a report for Equitable Growth titled “A communications oligopoly on steroids” that is even more relevant today. They write: “Only with appropriately focused regulatory oversight alongside strict antitrust enforcement can the service providers in the cable, telecommunications, wireless, and broadband industries be driven to offer competitive, nondiscriminatory, innovative, and socially beneficial video and broadband services that maximize consumer value and choice in both the economic market and the marketplace of ideas.”

Worthy reads not on Equitable Growth:

- Gabriel Zucman comments on the World Cup and tax evasion in “If Ronaldo Can’t Beat Uruguay, the Least He Can Do Is Pay Taxes.” Zucman writes: “Have you ever been invited by a Swiss bank to a golf tournament in Miami or an exhibition’s opening in Paris? Neither have I. But the world’s ‘ultrahigh-net-worth individuals’—whether they live in the United States, France or elsewhere—regularly are. Law firms and financial intermediaries sell the superrich on shell companies, offshore bank accounts, trusts and foundations—arrangements whose purpose is to conceal assets by disconnecting wealth, and the income it generates, from its actual owner. Although this industry presents itself as legal and legitimate, in many cases the products it sells are illegal.”

- Janos Kornai notes in “Speaking for Open Inquiry at the Central European University” that “I am very proud to have been awarded the Open Society Prize. … CEU does more than merely advocate the idea of university autonomy, the fundamental principle of the world of universities that goes back hundreds of years. CEU embodies that idea in the way it works, giving us an example of how to put it into practice. The life of CEU is characterized by free debate, discussion of conflicting ideas, competition between schools of thought, openness to alternative principles, and diversity. Ideas do not recognize borders, do not apply for entry or exit visas.”

- Given the magnitude of the shocks that have hit the world economy since 2005, then-Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan’s decision in the mid-1990s to set the Fed’s inflation target at 2 percent per year rather than 3 percent or 4 percent per year looks like a bad mistake. Given what they learned and what we have been learning since 2005, his successors Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen, and, now, Jay Powell’s refusal to revisit Greenspan’s decision is more likely than not to prove a worse mistake. So, I go further out on this limb than does the very sharp Karl Smith in “Hey Fed, Don’t Be Scared of a Little More Inflation,” in which he writes that “even if the economy is at full employment, there’s benefit to letting it run hot for a while.”

- Required for equitable growth is predictability: established rules of the game and due process of law. Also required: an activist government willing to create and support the communities of engineering practice and the essential services that underpin the highly productive value chains of the future—plus a willingness to enforce an equitable income distribution. Ricardo Hausmann fears that the United States—at least the Trump-dominated United States—has none of these. Read his “Does the West Want What Technology Wants?,” in which he writes: “to ascertain what technology wants requires understanding what it is and how it grows. Technology is really three forms of knowledge.”

- The ability to plan your family while being sexually active was a huge liberating force for young American women in the mid-20th century, write Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz in “The Power of the Pill: Oral Contraceptives and Women’s Career and Marriage Decisions.”

- It is not clear to me that equal percentage income boosts relative to the baseline is what we “should” expect education to do. That we fall short of even that yardstick indicates that things are worse than I had believed. Noah Smith in “The Rich Get the Most Out of College,” writes: “Tim Bartik … Brad Hershbein found that the college earnings premium—the lifetime difference in earnings between those who get a bachelor’s degree and those who only finish high school—was substantial for people from all income backgrounds.”

- “Perhaps smack of desperation, and … a tighter relationship with other parts of government”—those were the arguments of Vince Reinhart in 2003 against the aggressive policies (such as currency depreciation, money-financed tax cuts, discount-window lending, purchases of corporate debt and equity, and reductions in reserve requirements) that Ben Bernanke had previously argued a central bank should follow at the zero lower bound. But if you maintain your independence by not doing the right thing, then you were never independent in the first place. And desperation is the appropriate response to being at the zero lower bound on interest rates—it is a desperate situation. I think that somehow Bernanke (and Reinhart, and the Fed) came to believe that “encouraging investors to expect short rates to be lower in the future than they currently anticipate; shifting relative supplies to affect risk premiums; oversupplying reserves at the zero funds rate” had a good chance of being effective. It was not clear to me why they should have thought this. And it looks like they were wrong. Read Laurence Ball (2012): “Ben Bernanke and The Zero Bound.”

- The search for “robust determinants” has always seemed to me to be wrong-headed. We should be searching for effective policies. Which determinants are “robust” will depend on what other determinants are in the mix. And an effective policy is likely to shift the values of more than one “determinant,” writes Dani Rodrik on Twitter, in “Is ‘export sophistication’ (as in Hausmann, Hwang, and Rodrik 2007) the only robust determinant of economic growth? Robust, that is, to correcting for endogenity and OVB as best as possible? This new paper from the IMF says yes https://t.co/C3DkRzqr8d…”