Antitrust and competition issues are receiving renewed interest, and for good reason. So far, the discussion has occurred at a high level of generality. To address important specific antitrust enforcement and competition issues, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth is launching a new blog entitled “Competitive Edge.” This series will feature leading experts in antitrust enforcement on a broad range of topics: potential areas for antitrust enforcement, concerns about existing doctrine, practical realities enforcers face, proposals for reform, and broader policies to promote competition. We are honored that Fiona Scott Morton, has authored our inaugural entry.

The octopus image, above, updates an iconic editorial cartoon first published in 1904 in the magazine Puck to portray the Standard Oil monopoly. Please note the harpoon. Our goal for Competitive Edge is to promote the development of sharp and effective tools to increase competition in the United States economy.

Last month’s court decision allowing AT&T Inc. to acquire Time Warner Inc. is an example of the inability of our current system of courts and enforcement to prevent the decline in competition in the modern U.S. economy. In the case of that merger, the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice gets credit for making an attempt to block what it viewed as an anti-competitive transaction. What’s more, that view proved prescient after the now-merged firm almost immediately raised prices after executives testified that the synergies from the deal would immediately cause lower prices.

The court decision of U.S. District Judge Richard Leon demonstrated a lack of understanding of the markets, the concept of vertical integration, corporate incentives, and the intellectual exercise of forecasting what the unified firm would do. And so, not surprisingly, it produced a poor decision. The Supreme Court decision in Ohio v. American Express Company further weakens antitrust enforcement by complicating the analysis and raising the standard of proof for platform business cases.

There are many other settings where consumers deserve similar efforts to protect competition and where the two federal antitrust agencies have yet to take enforcement steps. This spring, both Bruce Hoffman, director of the Bureau of Competition in the Federal Trade Commission, and Makan Delrahim, assistant attorney general at the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division, have publicly called for assistance in both finding new cases to bring and developing theories of harm. Fortunately, a new volume of The Yale Law Journal—bringing together top antirust scholars and papers presented at a conference last fall that was co-hosted by the American University Washington College of Law and the Washington Center for Equitable Growth—has just come out to meet this pressing need.

The recommendations in the issue do not require novel applications of antitrust law or innovative interpretations of antitrust law. They are low-risk and high-return cases for U.S. antitrust agencies to bring. But enforcement in these areas will require the agencies to look beyond old markets with lots of precedent, and instead analyze the products that consumers are now buying such as online hotel bookings, credit cards, technology standards, and mutual funds, or markets where consumers are selling such as labor markets. These are markets that do not have established jurisprudence or a recent history of enforcement, with the notable exception of American Express. More novel cases are harder to bring because an existing draft complaint is not already sitting in the files of the enforcement agencies.

The papers in the issue of The Yale Law Journal identify the types of cases the agencies should be pursuing such as anti-competitive most-favored-nation clauses. Consumers are buying ever-more goods and services online, and yet the contracts governing those prices have been subjected to no scrutiny in the United States. In Europe, an online travel agent such as Expedia Group Inc. may not require a hotel to keep its price equal or higher at all travel agencies that compete with Expedia; hotels are expressly allowed to give whatever discounts they prefer to different travel sites. In contrast, this price-increasing behavior remains effectively legal in the United States.

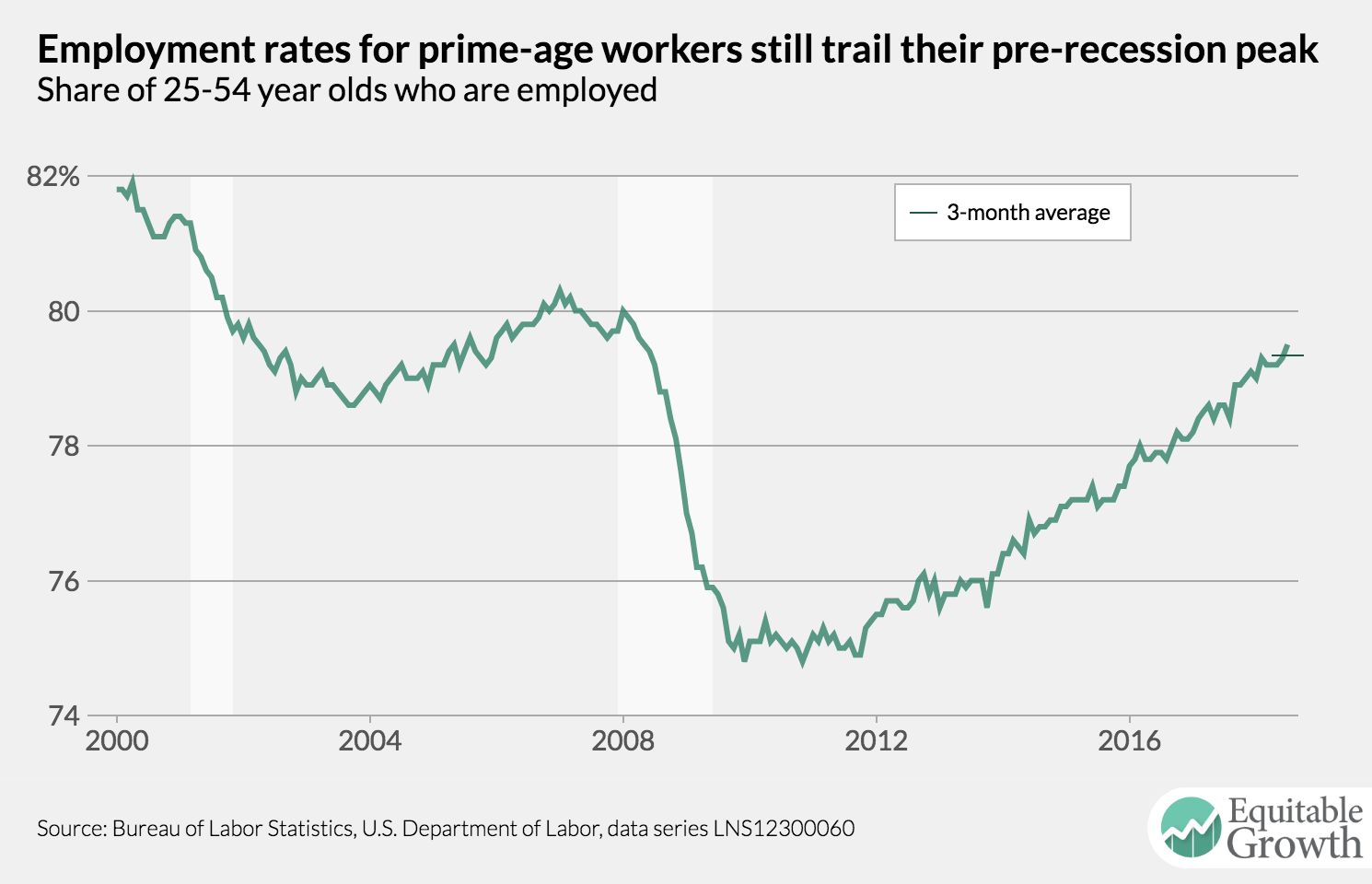

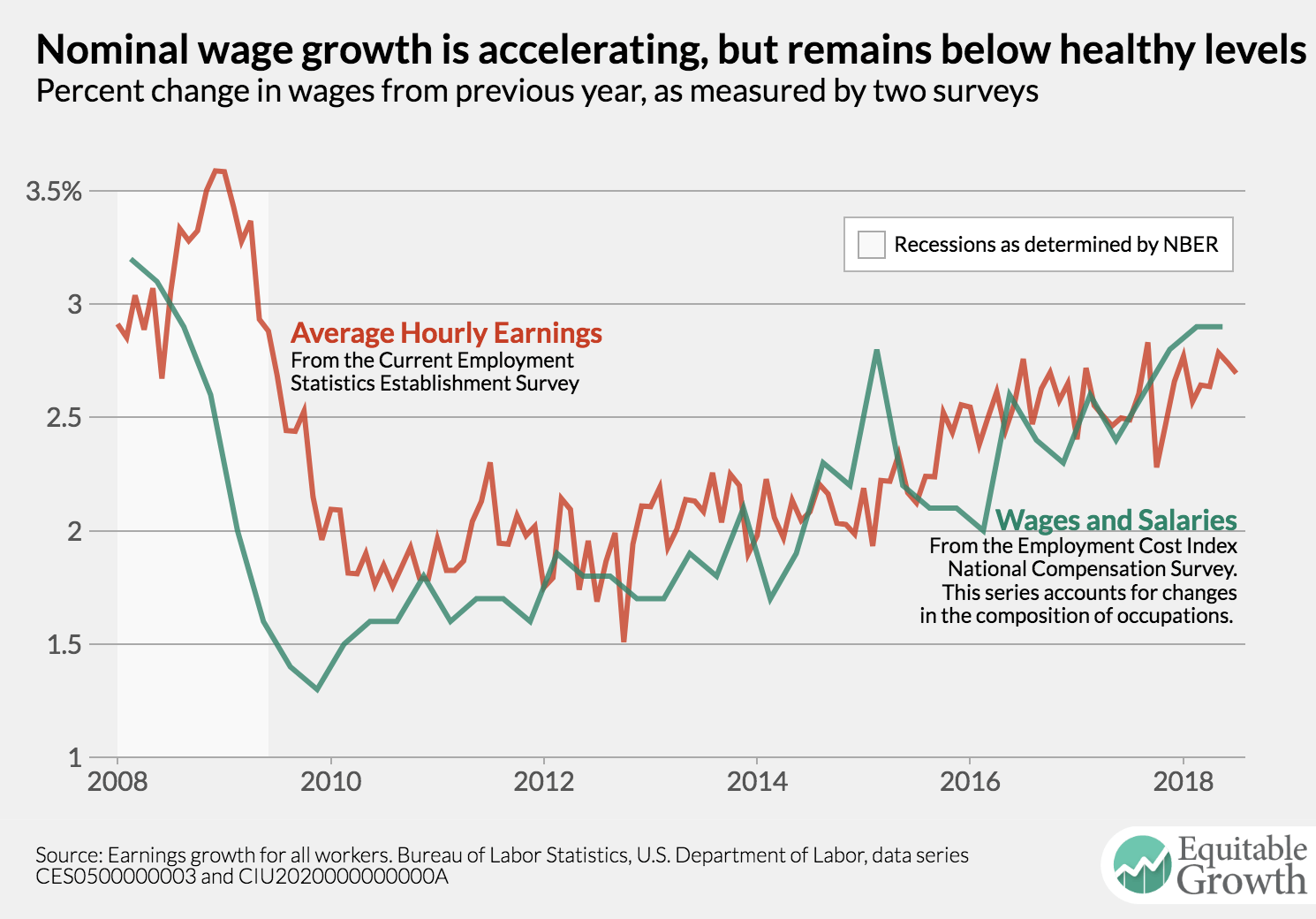

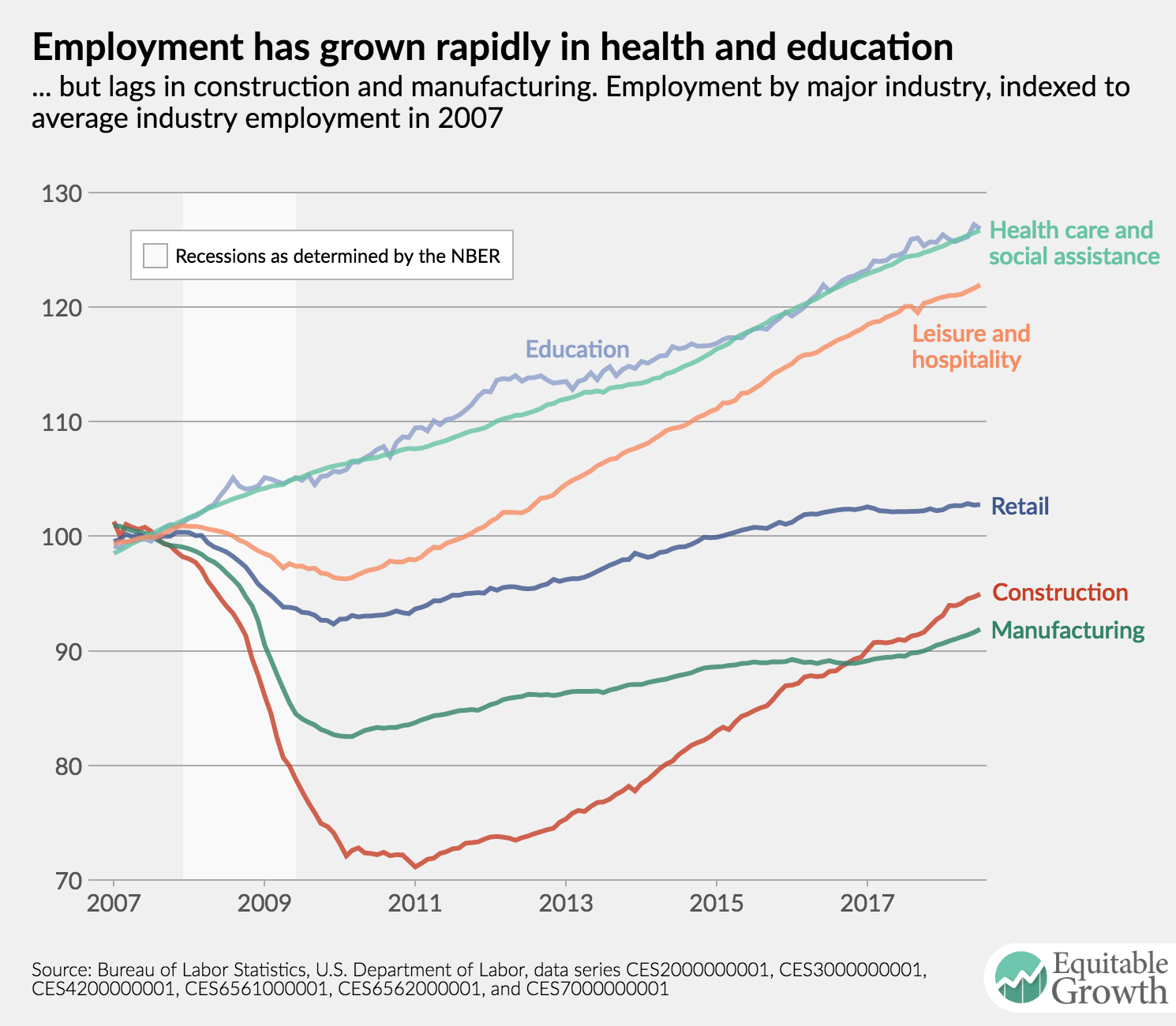

The Yale Law Journal issue also lays out the rationale for the agencies’ bringing cases involving harm to sellers, including employees, as this is a source of anti-competitive harm as much as higher prices. With some exceptions, antitrust enforcement has typically stayed away from these kinds of cases. Whether due to fear, doctrinal uncertainty, or misperceptions, this disclination should change.

Then there is the argument for using antitrust enforcement to end abuse by standard-setting organizations. New technologies are a key area where enforcement must keep up with consumers’ purchasing habits. Communication standards (such as those found in cellular technology—for example the so-called Long-Term Evolution standard), which are set by a standard-setting organization, often define the boundaries of competition. By a variety of conduct, some patent holders have exploited this standard-setting process across many technologies to undermine competition and harm consumers. Absent antitrust enforcement, this abusive conduct could delay the roll-out of the Internet of Things or increase its cost. The Yale Law Journal articles make a compelling case that economic theory and empirical evidence strongly support such actions. Although under Assistant Attorney General Delrahim—an acknowledged patent hawk—DOJ action protecting consumers in this area is unlikely, but at the FTC, Chairman Joe Simons was active in this area in his previous role as the FTC’s director of the Bureau of Competition, bringing the Rambus and Unocal cases.

Second, there are areas where the agencies may need to defend current doctrine or push back against mistaken doctrine. This category includes reaffirming the presumption in horizontal merger cases, redoubling efforts on vertical mergers after the AT&T-Time Warner decision (with full credit to the DOJ for bringing the case), and pushing back on doctrines that appear to limit the role of antitrust in pursuing predation cases. Further, in times of deregulation, active and vigorous antitrust enforcement is even more critical.

Multisided platforms such as credit cards, news sites, and auctions present old economic theories in a new setting, which courts find confusing. Although the Supreme Court’s recent decision in the American Express case limits the government’s ability to enforce the antitrust laws, the agencies must continue to be aggressive in their defense of competitive markets. Many platform cases will need to be brought promptly in order to clarify just how much protection from the antitrust laws the American Express decision will give these businesses.

Finally, there are important new areas for enforcement that require study of the kind only the agencies can do. Mutual funds that hold significant stakes in competing firms, such as the largest four domestic airlines, have the potential to lessen competition. The agencies have the power to examine communications between mutual funds and the companies they hold. Without such study, policymakers cannot learn the true impact on markets of many large, common owners. If that impact turns out to be significant and enforcers have done nothing to learn about it, then they will contribute to exposing U.S. consumers to more anti-competitive harm.

In its entirety, The Yale Law Journal issue lays out an initial roadmap of cases that are well-grounded in economic analysis and legal precedent. Enforcement in these areas would make U.S. markets more competitive. I have mailed a copy of this issue to both Chairman Simons and AAG Delrahim in the hopes that they find the content responsive to their call for enforcement assistance from the academic community. Each author has kindly agreed to answer any questions the agencies might have about their articles. I look forward to seeing the enforcement choices of these agencies in the year ahead.

I will close by, noting that this recent issue does not even analyze the conduct of the large technology companies that we often hear concerns about today. In the legislative realm, the U.S. Congress needs to increase the staff (with a larger budget) at both agencies to allow them to match their enforcement efforts to Gross Domestic Product. Competitive problems grow with the economy, but we have let our enforcement efforts stagnate. There is much still to do in this area to protect competition in the United States and the American consumer.

—Fiona M. Scott Morton is the Theodore Nierenberg Professor of Economics at the Yale University School of Management.

Letters

Click to read the full letters.