Overview

“Equitable Growth in Conversation” is a recurring series where we talk with economists and other social scientists to help us better understand whether and how economic inequality affects economic growth and stability.

In this installment, Equitable Growth’s Executive Director and Chief Economist Heather Boushey talks with Michael R. Strain, the John G. Searle Scholar and the director of economic policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, about the importance of government data collection for our democracy and our understanding of the U.S. economy over time and into the future.

[Editor’s note: This conversation took place on April 30, 2018.]

Heather Boushey: Michael Strain, thank you so much for being here today. This is just great.

Michael Strain: I’m very happy to be here.

Boushey: I want to get right into the questions I want to ask you today. You write a lot about about government data collection with Diane Schanzenbach, the director of the Institute for Policy Research and Margaret Walker Alexander Professor of Human Development and Social Policy at Northwestern University. And you say that working on data together is a small investment with a big payoff. Can you explain that? What’s the payoff of government data? Who’s using it? What are they getting out of it? Explain to me why you and Diane think it’s a big bang for the buck.

Strain: It’s a big bang for the buck for two reasons. One is the cost of mistakes. Think about what government data are used for by policymakers. The Federal Reserve, for example, looks at information on unemployment, looks at information on price inflation, and then tries to decide what to do with interest rates. Or consider Social Security benefits, which are adjusted by policymakers based on a price index that the government produces. If the price index or if the unemployment rate are measured with a little bit of error, then Social Security benefits could be too low, or they could be too high, or the Fed could tighten too early, or the Fed could tighten too late.

When you consider how large a check the federal government writes for Social Security benefits every month, when you figure how important interest rate decisions are to private businesses, those small errors really add up. And they really result in big expenditures for Social Security, big macroeconomic effects. So, when you compare the cost of producing those statistics to the cost of errors—even small errors—then the cost-benefit really works out such that you want those data to be as accurate as possible.

The other big bang for the buck is that businesses use government data to decide what items to put on the shelves by using information about the demography of their local customer base. Businesses use government data to decide where to open distribution centers, where to open warehouses, and where to open new stores, and where to do all sorts of things. Businesses are just constantly relying on data. So, relative to a lot of things the government does, data are pretty cheap to produce, and we might as well do it right.

Boushey: I understand you wrote that the amount of money that the federal government spends on government statistical agencies is about one-fifth of 1 percent of the federal budget. That’s not a lot. Is that your understanding of what the number is?

Strain: Yes, it’s not a lot.

Boushey: It’s really small. I often think of the weather services, right? All of the data that we have on what’s going on with the weather is coming from government data and satellites. We are getting it through all of these private entities that are, maybe, presenting it in prettier graphics or ways that we can understand, but you need to have that data accurate for us to make good decisions about what to wear in the morning.

Strain: Yes, and that’s a good example of how much government data kind of intersect with our day-to-day lives in ways that we may not even know. A lot of people pull up an app on their phone every morning to see what the weather’s going to be. But not that many people who are doing that really understand that the Federal Statistical System is what’s allowing that information to be possible.

Boushey: So, my next question. Why should this be a government function rather than a private-sector function? After all, the private sector produces a lot of data from the club card at the grocery store or the drug store when it tracks all of your purchases or your bank or whatnot. And there’s some overlap with what private-sector entities do and what government statistical agencies do and what academics do. So, why is it that having government data is so important?

Strain: Certainly, the data revolution from private-sector businesses is great. And all that data is a really important complement to the data that are produced by the government—a positive development for both researchers and businesses especially. But I think looking at data that are generated by private businesses as a complement to government statistics, rather than as a substitute for government statistics, is the right way to look at it.

The data that government produces are designed to be nationally representative. You want to know what the unemployment rate is for the U.S. economy as a whole. You want to know what’s happening to the prices that a representative consumer is facing in the aggregate. That’s not what private businesses are doing. They want to know about their customer base; they want to know about their potential customer base. The data they’re gathering are often gathered as a part of doing business, and so they are just not directly comparable.

In addition, part of the design of some of these government datasets is based on the desire to be able to make comparisons over long periods of time. You want to be able to ask, “What is the median income in 2018?” and then be able to compare that to median income in 1998. And to be able to have that comparison be meaningful, you need to make sure you’re measuring the same thing over time. Private businesses just aren’t in a position to have that as a goal, and that wouldn’t be a good goal for them, for the most part.

So, there are important functions that government data serve that are not well-served by the kind of efforts that private businesses engage in when they’re kind of creating all this data. But, again, they’re complementary. And they’re both important.

Boushey: If the president made you data czar for a day, give me a couple of places where you would focus to make government data collection better, more comprehensive?

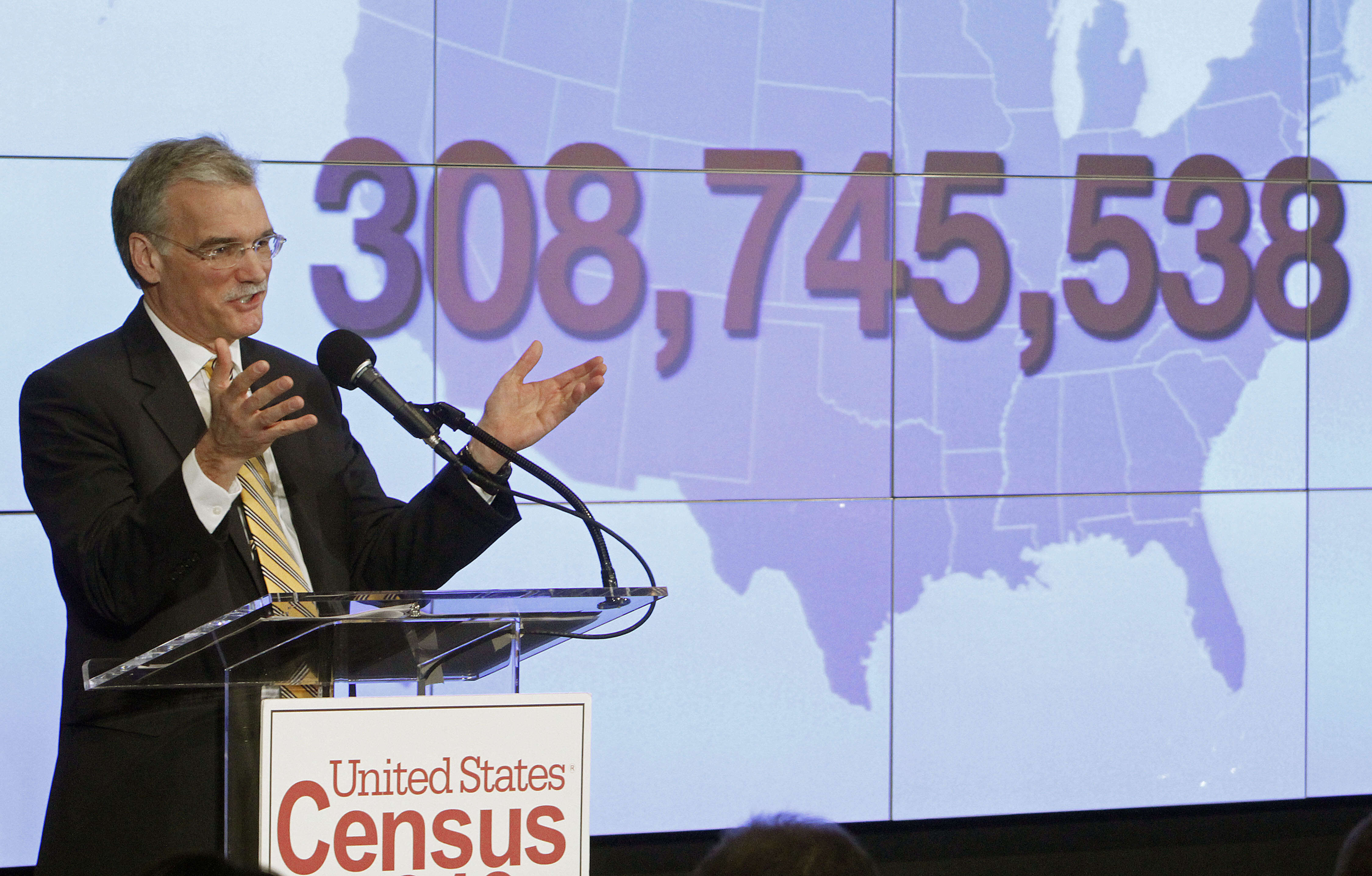

Strain: I think the most immediate need right now is making sure that the 2020 decennial census is adequately funded and is as successful as we need it to be, which may seem like a weird answer when you’re thinking about immediate need since it’s now 2018. But it really does take many years of planning and preparation to execute a successful decennial census. The census is not a standard government survey, where you pick 20,000 or 200,000 households. This is an exercise that requires everybody to be counted. If you don’t fill out the form online or fill out the pencil-and-paper form and mail it back in, then the government has to send somebody to your house with a clipboard. That’s the extent to which the government takes this seriously.

And it should be taken seriously because it’s required by the Constitution. It’s how we apportion seats in the U.S. House of Representatives across the states, among other functions. Because it’s an enumeration, because everybody’s counted, the decennial census is used as a benchmark for many, many, many other government data products. And so, if there are errors in the decennial census, we live with those for 10 more years. Because we benchmark other government surveys against the census data, if the census data are wrong, then the benchmark’s wrong—and the other surveys are wrong, too.

So, we have to make sure this is adequately funded. We have to make sure the census has the resources it needs. If part of being a data czar means I get to appoint a head of the Census Bureau, I would do that, too. Because, currently, there is not a head of the Census Bureau.

Boushey: I could not agree with you more that this is just absolutely mission critical. You wrote a piece on this, and in your very first paragraph, you talk about how it’s required by the Constitution, Article I, Section 2.

Strain: That’s right.

Boushey: And that data are used for so many things. How can you know how many people should be in House districts, or other state and local districts, if you don’t have a good count of the people? Every year, hundreds of billions of dollars of federal funding is given to the states based on population. And those population estimates come from the decennial census.

Strain: Even in addition to all of that—which is, obviously, critically important to the functioning of our democracy—there are just all sorts of downstream ramifications to making sure that the 2020 census is as accurate as it can be. And it’s not receiving the amount of attention that I think it should. And in part that’s because it’s two years away, and in Washington anything that’s more than three days away is in the distant future. But this really is such a big undertaking that it really does require years and years of planning.

Boushey: A big part of this undertaking is going out into the field and making sure that the technology works, and that people know how to ask the right questions. But because of funding issues this year, they were supposed to do four tests but they’re only going to do one. Which, as a researcher, makes me a little anxious. And I understand they’re using new technology this year—they’re going totally online.

Strain: That’s one of the reasons why we need those end-to-end tests, to see if people are actually comfortable doing that. If the Census Bureau decides, “OK, this group of people, for whatever reason, are going to be more likely to respond online, so we’re going to send them the online-only version” and half of them don’t respond, then the bureau can’t just say, “Oh, OK, we tried.” The bureau has to send the paper-and-pencil version; it has to send somebody to these people’s houses. And that’s when you start racking up the expenses and the amount of taxpayer dollars you need. If we spend a little more money now, we’ll probably save money on the total cost conducting the census.

Boushey: That’s the second time you’ve mentioned that part of what we’re looking at with the data issues is making smart investments and doing the right thing up front so that we’re not paying more in the end. I think that’s a really important theme. I would also note that the previous time we did the census in 2010, it was in the middle of the Great Recession. And so a lot of people needed jobs, so it was easier, probably, to find census-takers than it would be now, when we’re closer to full employment. I don’t know if they’ll have to pay more for that, but I would imagine that getting people to go out there with pen and paper is going to be more expensive or harder to find people than before.

Strain: Yes, that could be the case.

Boushey: Another thing that could drag down the number of people who are responding is this new addition that the Department of Commerce decided to add, a question asking respondents if they’re citizens. You’ve written that this would damage the accuracy of the census. I want you to walk us through that argument. But first, I would like to preface it with a story about why my housemate in NewYork City in 2000 refused to fill out the census form because he was concerned about privacy. At the time, I was a researcher and I was using census data, so I asked, “What are you talking about? Why are you so anxious about doing this?” He had a college degree, had a good job, was not an immigrant, so there was no reason for him to be afraid, and yet he was. And it really struck me how hard it is to communicate to people that they should hand over their information to the government.

Strain: The best place to start is with what’s actually on the form. It’s very basic information. It’s a very short form, basic questions such as “How many people live in this home? What are their ages? What are their sexes?” Very, very basic stuff that your neighbors probably know about you just by observing you. The point is to count the population and make sure that we know how many people there are in the United States.

Even given how simple and basic that is, every 10 years, members of immigrant communities and members of certain minority communities get a little spooked by the prospect of handing over this basic information to the government—especially when the information is requested in person, which is what happens when you don’t fill out the initial form. And when the Census Bureau was out conducting some interviews trying to prepare for the 2020 census, it discovered that although during a typical year there’s some anxiety those communities, in 2017, there was much, much more anxiety among immigrants and among certain minority communities. It’s not hard to understand why. There’s a lot of really ugly rhetoric coming out of D.C. about immigrants, including from the president of the United States, both after he took office and, of course, while he was was a candidate. And so there’s this kind of atmosphere out there that makes people reluctant to fill out the form.

For people who use government data all the time for their research, that reaction may seem odd. But I think there’s no denying that it’s the case. Add on a really sensitive question about whether you’re a citizen, and the concern that I have—and that many others have—is that that’s going to really spike the anxiety level. Some members of these immigrant communities and these minority communities are already feeling more reluctant to answer the questions, or will answer the questions inadequately out of concern for their privacy, or whatever. But because of the way that immigrants have been discussed by top elected leaders, including the president, it’s understandable why it would be even more of an issue this time around.

Boushey: So, if it does turn out that the citizenship question depresses response rates among certain groups, what are the practical implications?

Strain: Well, it’ll end up costing more money because it means more people have to be hired to go and knock on doors.

Boushey: Last question. One of the things that we do here at Equitable Growth is that we are a grantmaking institution. We’ve funded about 130 scholars nationwide at universities and given away almost $3 million now, over the past almost-five years. As you’re thinking about these issues around data and data collection, what advice would you have for us? Is there any particular issue areas or kinds of data that you think we should be investigating or spending more of our resources to understand or work on?

Strain: We have a statistical system that’s kind of built around a 20th century economy. So, to the extent that you are figuring out ways to update this statistical system to account for the way that we live and work now would be important. But more importantly, to account for the ways that we might live and work 20 years from now, to really have a plan to have statistically valid surveys that capture the information that we want to capture is, I think, a very worthy research program.

Boushey: Thank you. This has been just illuminating. I really appreciate your time.

Strain: Thank you.

Related

Explore the Equitable Growth network of experts around the country and get answers to today's most pressing questions!