Worthy Reads on Equitable Growth:

- I have not yet welcomed the extremely sharp Kate Bahn to Equitable Growth: Kate Bahn: “Her areas of research include gender, race, and ethnicity in the labor market, care work, and monopsonistic labor markets. … She was an economist at the Center for American Progress. Bahn also serves as the executive vice president and secretary for the International Association for Feminist Economics. … She received her doctorate in economics from the New School … and her Bachelor of Arts … from Hampshire.”

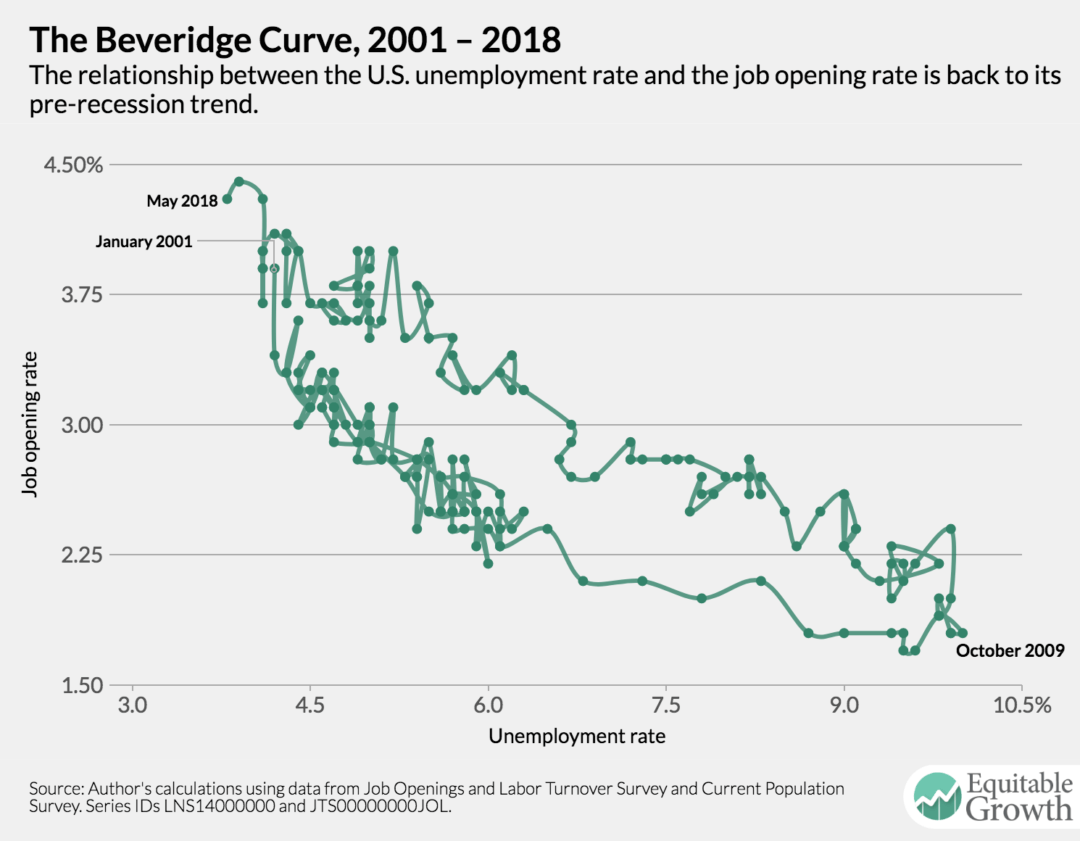

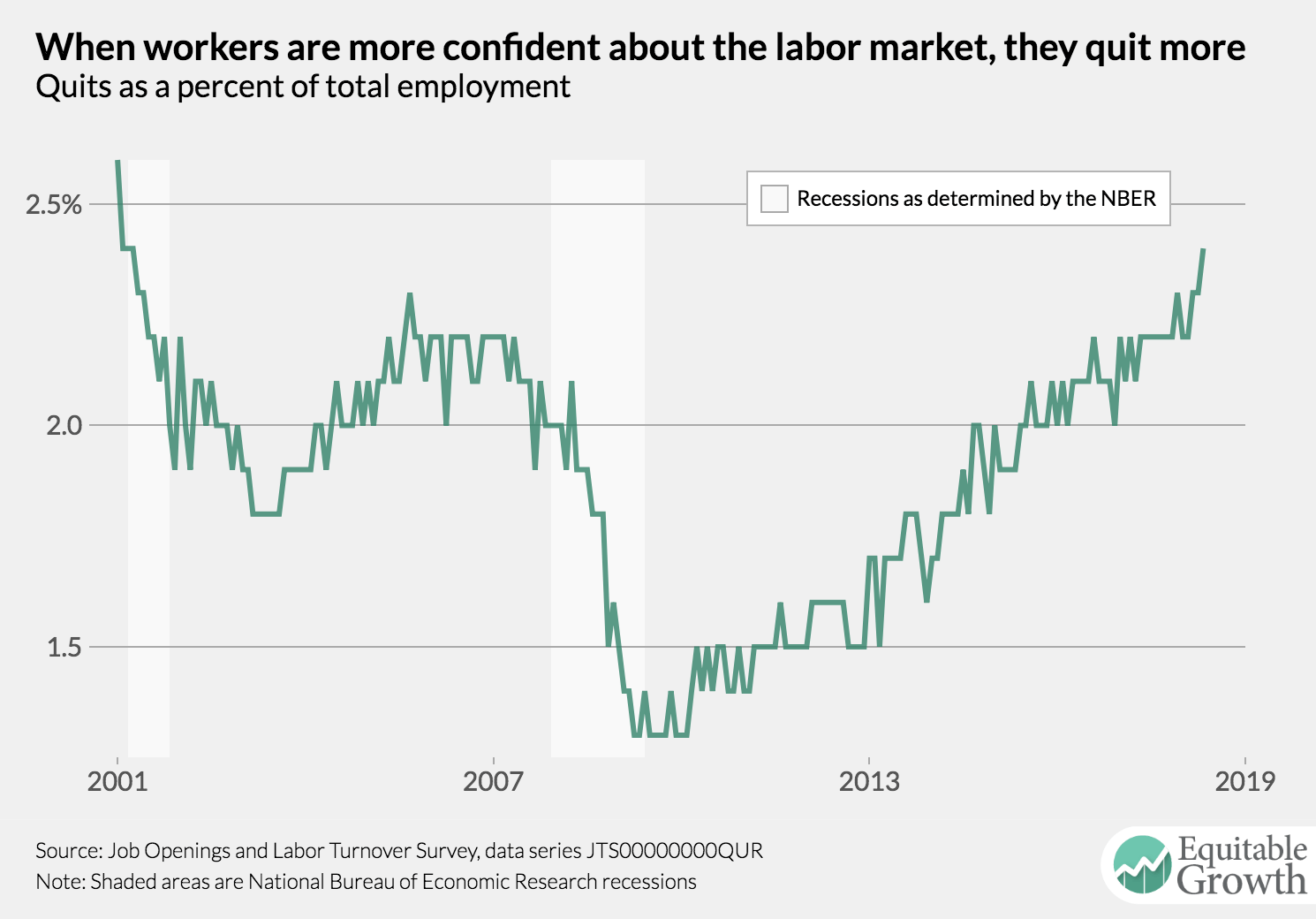

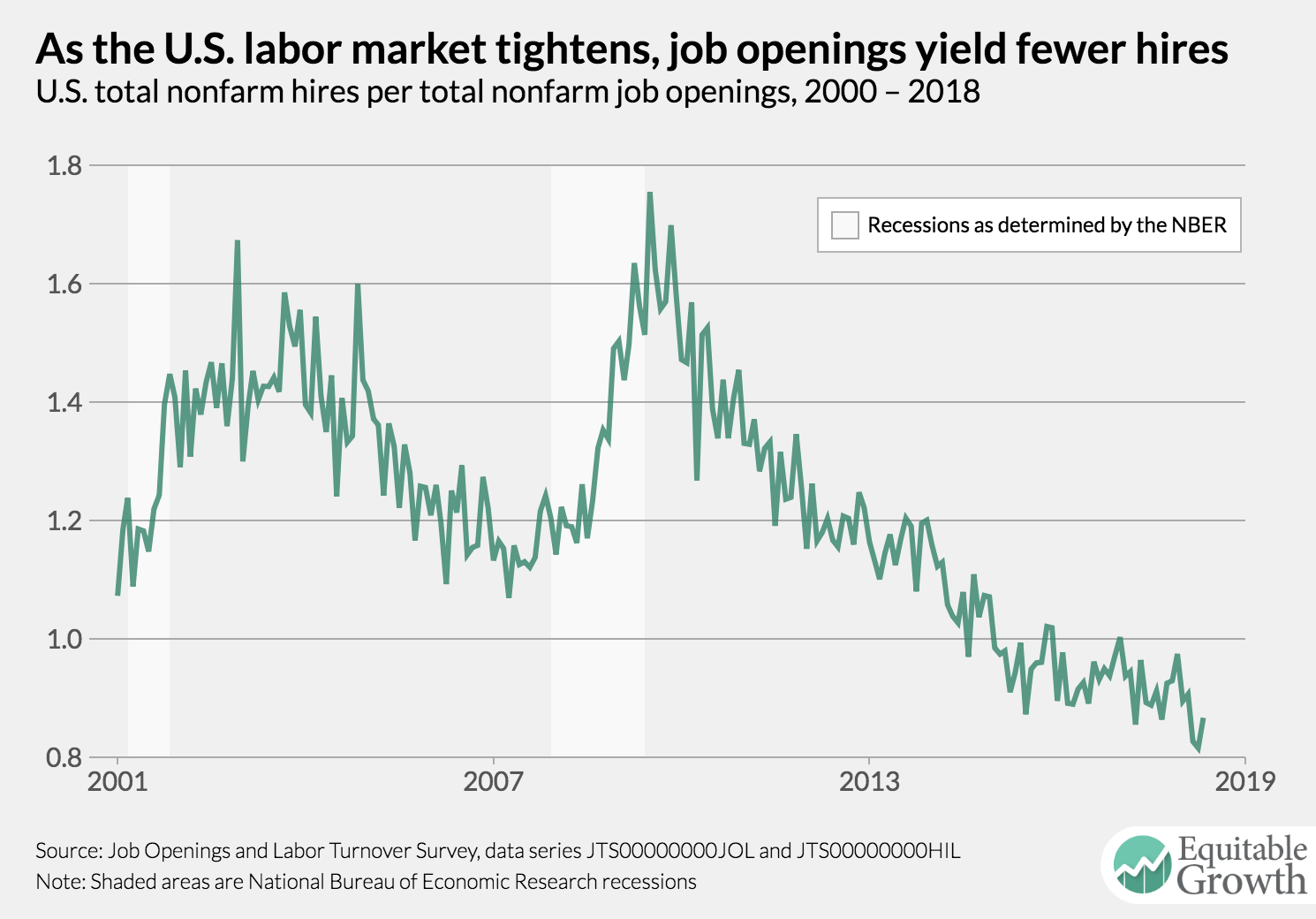

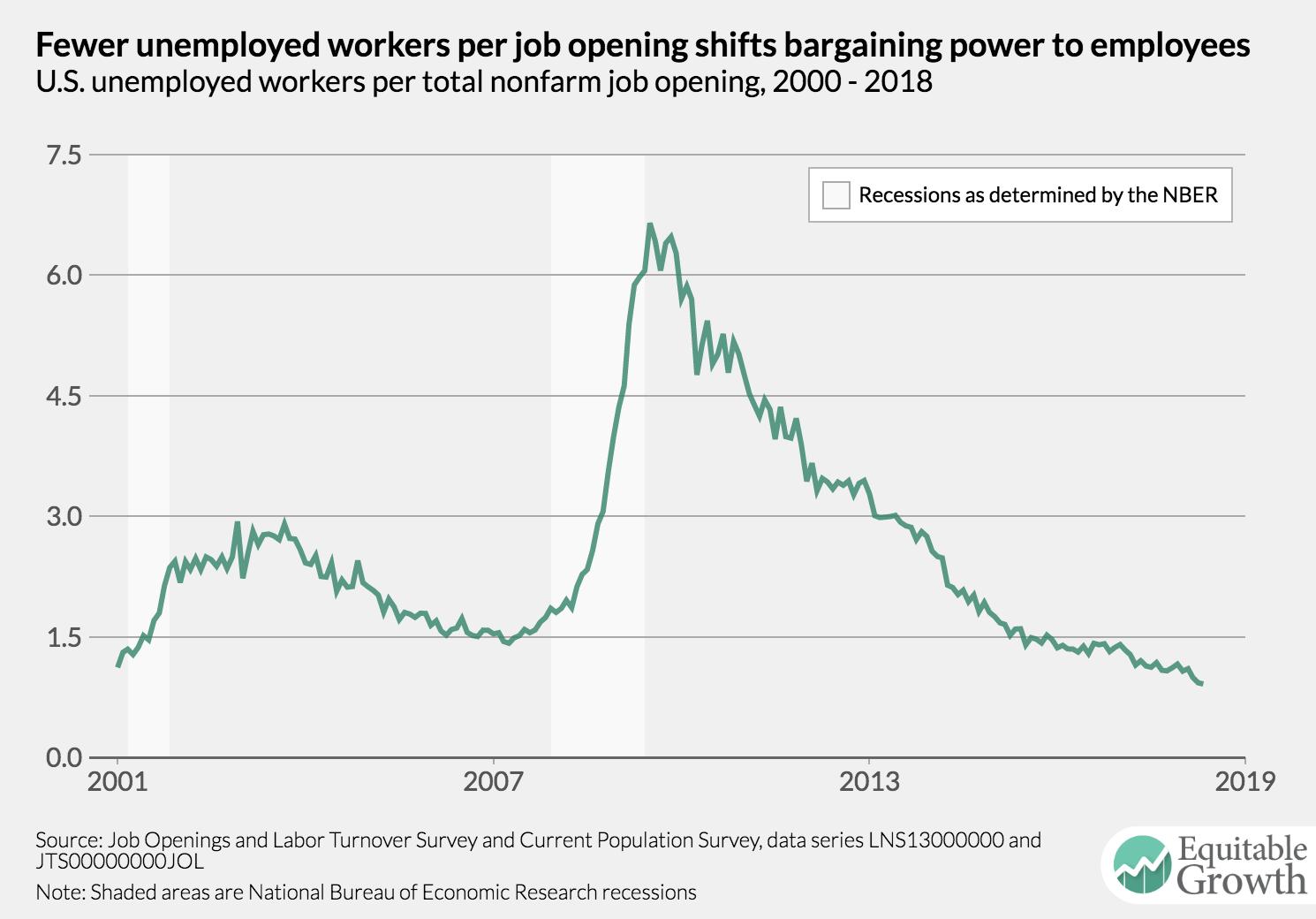

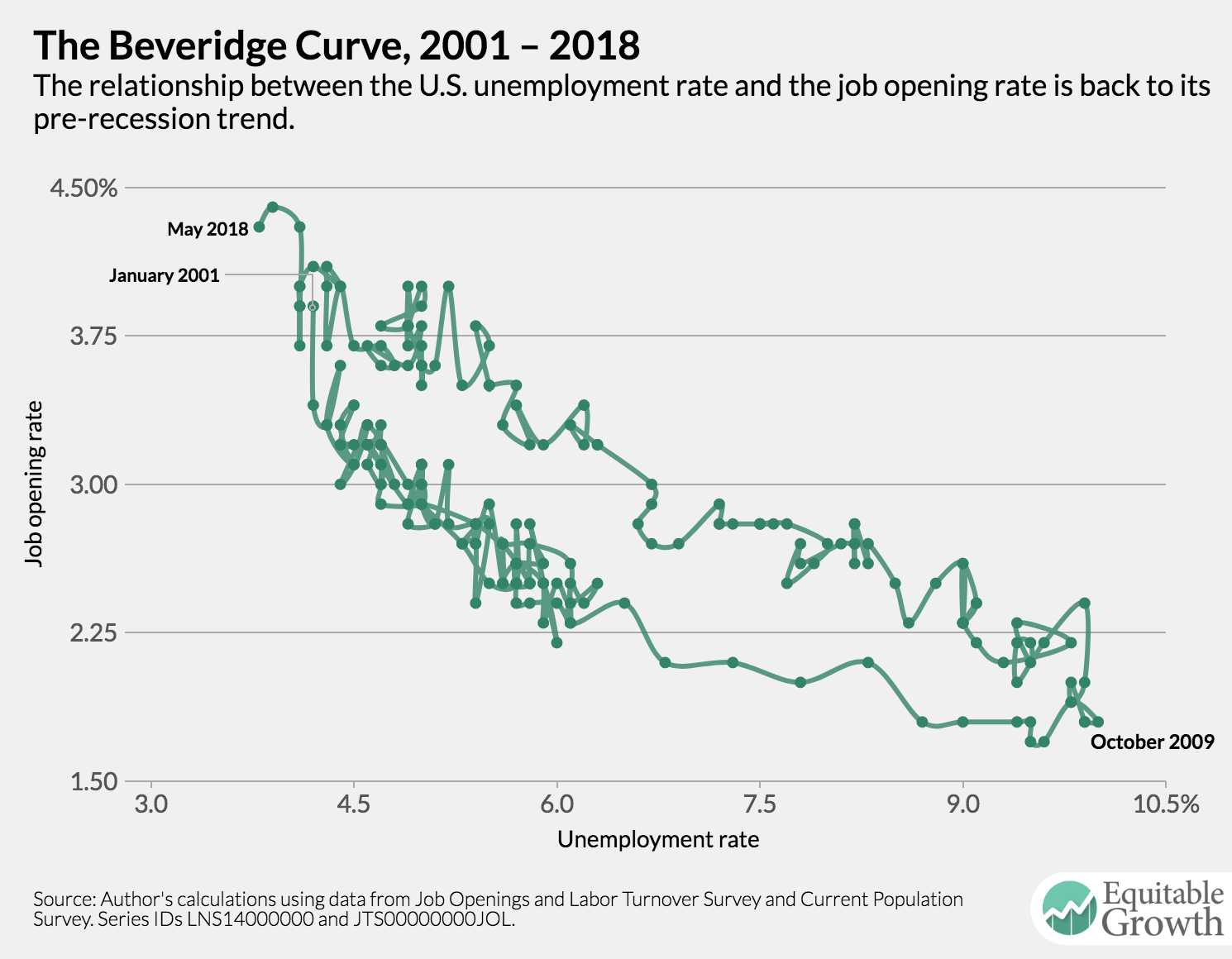

- Very much worth reading from Equitable Growth alum Nick Bunker: “Puzzling over U.S. wage growth,” in which he makes the point that “hiring has not been particularly strong during this recovery.”

Worthy reads not on Equitable Growth:

- Here is the website for Gabriel Zucman, Ludvig Wier, and Thomas Torslavon’s work on missing profits from tax avoidance and tax evasion (yes, I have decided I should spend some time occasionally listing paper authors in reverse alphabetical order): “The Missing Profits of Nations.”

- Wealth inequality measures have been grossly understating concentration because of tax evasion and tax avoidance in tax havens. This paper by Annette Alstadsæter, Niels Johannesen, and Gabriel Zucman estimates the amount of household wealth owned by each country in offshore tax havens: “Who owns the wealth in tax havens? Macro evidence and implications for global inequality.”

- The “optimal tax” literature in economics has always been greatly distorted by the fact that models simple enough to solve bring with them lots of baggage that leads to misleading—and usually antiegalitarian and antiequitable growth—conclusions that would not follow if we had better control over our theories. Here Emmanuel Saez and Stefanie Stantcheva make significant progress in resolving this problem: “A simpler theory of optimal capital taxation.” They begin: “We first consider a simple model with utility functions linear in consumption and featuring heterogeneous utility for wealth.”

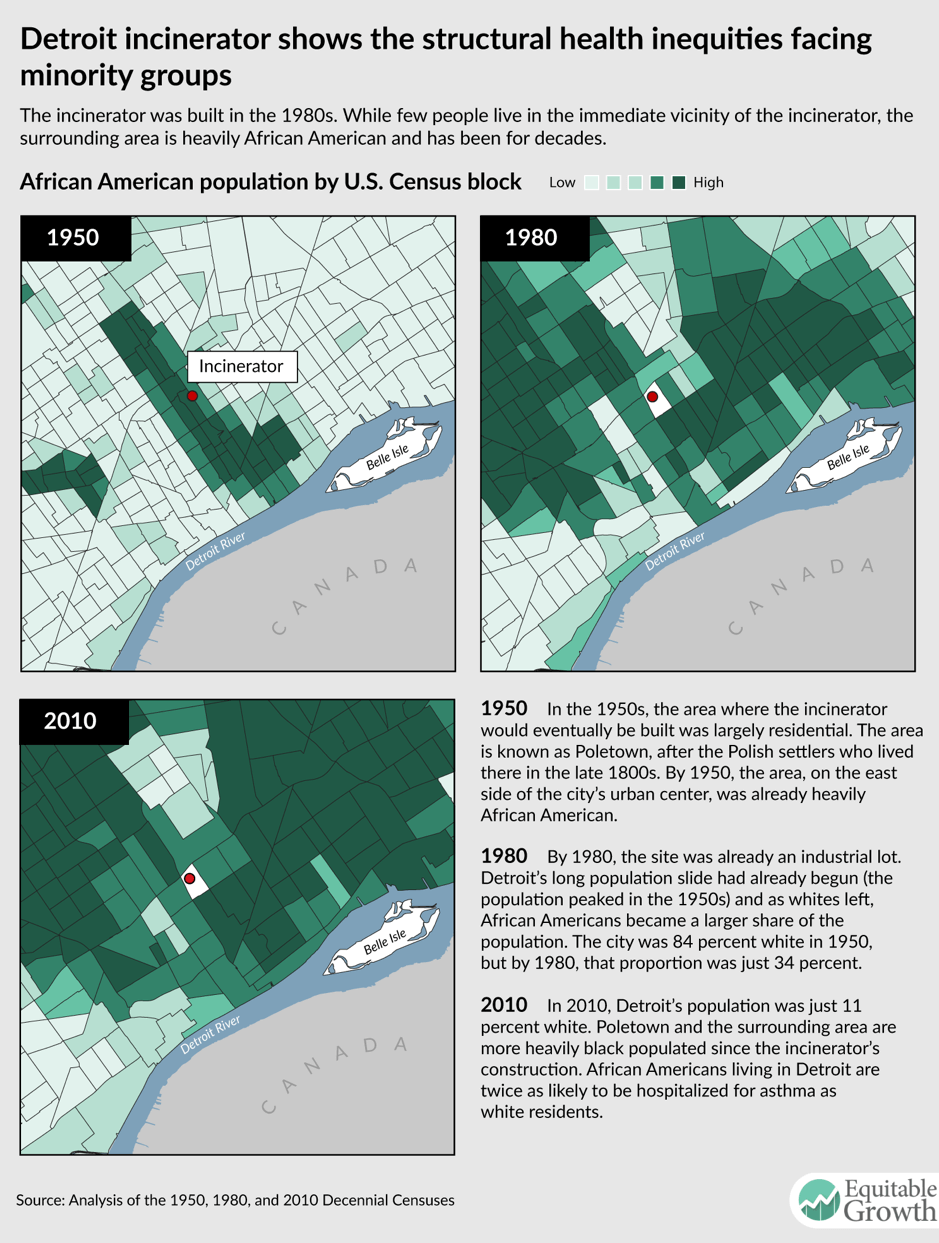

- I am genuinely confused here: Do we have an “eastern heartland” problem? Or do we have a “prime age male joblessness” problem? Those two problems would seem to me to call for different kinds of responses. Yet Lawrence H. Summers, Edward L. Glaeser, and Ben Austin are smooshing them into one in “A rescue plan for a jobs crisis in the heartland.” They write: “In Flint, Mich., over 35 percent of prime-aged men—between 25 and 54—are not employed.”

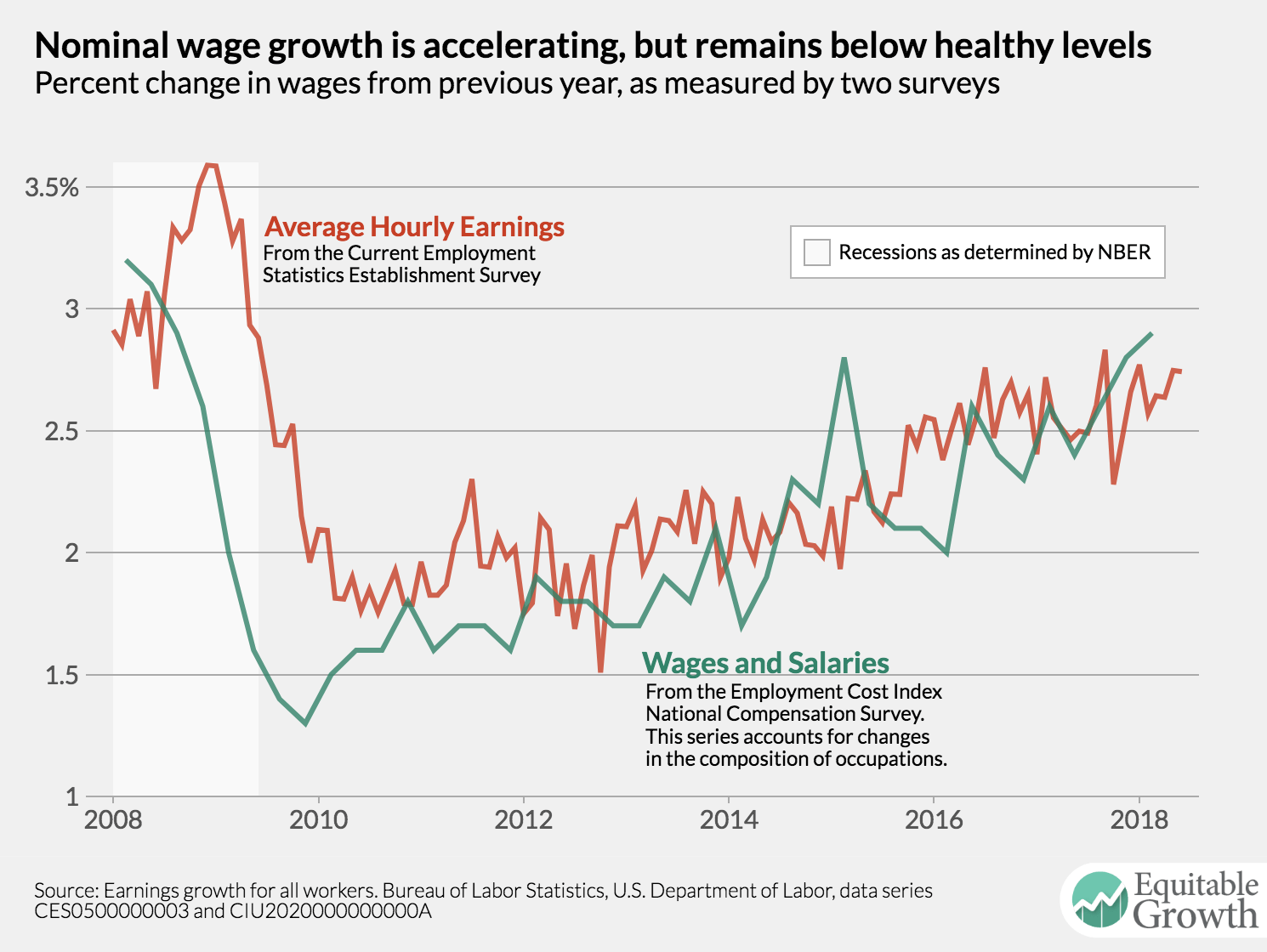

- I think that this is a very important thing to remember: The Fed’s view—and the zero-marginal-product workers view—and a lot of other pessimistic views about the economy’s noninflationary speed limit for recovery and growth were totally, catastrophically wrong over the past decade. The people who strongly advocated for such views thus had a badly flawed Vision of the Cosmic All. Thus I think there is no reason to put a weight higher than zero on their current views of how the world works—unless they have publicly and substantially done the work to mark their beliefs to market. Certainly the Federal Reserve has not yet done so, argues Timothy B. Lee in his Twitter comment that “Every additional month of strong employment growth and weak wage growth makes people who said we were near full employment in 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017 look wronger.”

- If real wages are not growing faster than productivity, then we are not yet at full employment. We aren’t, says Matthew Yglesias on Twitter: “I think it [a labor shortage] would be a good thing, but it’s also mostly fake. We had a labor shortage in 1999 and it was glorious. I think we’ll get there again. But not yet.”

- The Trump administration and the Republicans who enable it do not understand that disrupting value chains does not get you the benefits in terms of shifting the terms-of-trade in your favor that (with no retaliation) tariffs can in the “optimal tariff” literature when levied on finished goods. Read Chad P. Bown’s Twitter comment that “BMW says it will build more of its SUVs overseas and NOT IN SOUTH CAROLINA because of China’s retaliation on US autos in response to Trump’s tariffs.”

- People are not effective price-sensitive consumers for health insurance. We can argue why they are not. But first we need to admit that they are not, argue Zarek C. Brot-Goldberg, Amitabh Chandra, Benjamin R. Handel, and Jonathan T. Kolstad in “What does a Deductible Do? The Impact of Cost-Sharing on Health Care Prices, Quantities, and Spending Dynamics.” They write: “We leverage a natural experiment at a large self-insured firm that required all of its employees to switch … to a nonlinear, high-deductible plan.”

- The empirical studies are finding more and more hysteresis—in the sense of a persistent downward shadow cast by a recession—than I would have believed likely. I keep hunting for something wrong with these studies. But there are too many of them. And they all—at least all those published that cross my desk—point in the same direction such as Karl Walentin and Andreas Westermark’s “Stabilising the real economy increases average output,” They note that “DeLong and Summers (1989) … argue that (demand) stabilisation policies can affect the mean level of output and unemployment.”

- Here is another study that finds a lot of hysteresis—an ungodly amount—by Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer: “Why Some Times Are Different: Macroeconomic Policy and the Aftermath of Financial Crises.” They write: “Analysis based on a new measure of financial distress for 24 advanced economies in the postwar period shows substantial variation in the aftermath of financial crises.”

- I think this a very interesting framework presented by Daron Acemoglu, but it is, I think, too simple to be of material use in trying to understand what is going on in the real world: “Directed Technical Change.” He writes: “Whether technical change is biased towards particular factors is of central importance.”

- A paper I badly need to read—and to read today—by Talia Bar and Asaf Zussman, is “Partisan Grading,” in which they write: “We study grading outcomes associated with professors in an elite university in the United States who were identified.”

- Nick Stern is right: Discount rates are highly endogenous to scenarios—and go way, way down in true catastrophe scenarios in which insurance is not possible. Societal discount rates cannot be read off of imperfect capital markets. Climate change studies that start from either the assumption of a pure positive real intertemporal discount rate or from financial market perfection are, I think, as close to worthless as anything on God’s Green Earth. Read Nicholas Stern, “Public economics as if time matters: Climate change and the dynamics of policy,” in which he observes that “subjects such as the dynamics of innovation, of potentially immense and destabilising risks, and of political economy, together with technicalities around non-linearities and dynamic increasing returns.”

- How, again, is President Donald Trump supposed to win a breath-holding contest with an authoritarian regime that both controls its media and sees little downside in redirecting resources to cushion the impact on potentially noisy losers, asks Paul Krugman in “How to Lose a Trade War.” He writes: “Trump’s declaration that ‘trade wars are good, and easy to win’ is an instant classic, right up there with Herbert Hoover’s ‘prosperity is just around the corner.’”