When John Podesta began talking about establishing the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, the hope was to create a place where high-quality facts and analysis could speak. The hope was to set out goals that were broadly endorsed: Who, after all, would think higher productivity—growth—was bad? Who, after all, would think being fair—being equitable—was bad? And, without entrenched ideological or partisan dog whistles about what we were aiming for, pragmatism might have a chance: This would make us richer. That would make things fairer.

It was intended to be another contribution to creating a nation not of blue states and red states, but of purple states. It was intended to raise the level of the debate. It was intended to focus the debate on what was really important. That effort has faced some truly astonishing political headwinds over the past several years. And so that effort has been unsuccessful.

But that is no reason not to keep trying.

What is it that we are trying to do? As I grow older, I become more and more an organizational realist: The purpose of an organization is what it does, rather than what its mission statement says it is going to do. What the worker bees do determines what the organization does. What the planners and vision architects say does not determine what the organization does. Thus the task is to tune things so that the organization does what it does in an effective, productive, and useful manner.

So, here are a half-dozen examples of things that Equitable Growth does and has done very well—six exemplars.

John Schmitt’s interview with Sandy Darity

This interview with Duke University economics and public policy professor (and Equitable Growth Research Advisory Board member) William “Sandy” Darity Jr. focused on his work on “stratification economics.” Up until the Great Depression, the United States was a country of extraordinary social mobility, especially upward social mobility—but only for white guys. Since World War II, the United States has ceased to have even above-average social mobility. Why luck, plus the market’s desire to channel money not to the established but to the potentially productive, both have not done more to generate social mobility is something about which Darity has spent his career thinking—with much less of an audience than his ideas and efforts deserve. John Schmitt—who, alas, has since moved on to the Economic Policy Institute—does an excellent job of teasing out Darity’s thoughts on stratification and on American economics today as social practice.

Read John Schmitt’s Equitable Growth in Conversation: Darity: “I definitely don’t want to forsake the economics profession. I still have hope that there will be other, younger economists who will try to bring very fresh perspectives to the way in which we conduct economic research. I would encourage folks to go into the field, but I’d want them to have their eyes open. I think that they need to be very selective about which institutions they choose to attend to try to do their work. If graduate students have ideas that are not conventional or are unorthodox, then they need to have their eyes set on trying to identify departments that have the flexibility and open-mindedness to allow them to pursue the kind of approaches that they want to undertake.”

Austin Clemens, Robert Lynch, and Kavya Vaghul’s snapshot on universal pre-K

This snapshot was on the state-by-state benefits and costs of high-quality universal pre-Kindergarten. It used to be an oft-repeated line that the cure to bad speech is more speech. These days we are more likely to believe that the cure to good speech is more bad speech. Good, informative speech has to be well-crafted, arresting, and properly framed and pitched if it is to break through and become a durable part of the people’s knowledge base. Knowledge of what policies are likely to do on the ground for communities is scarce. And in a federal system, knowledge of likely state-level impacts is extremely important in shaping the environments in which policy is made. Here the Equitable Growth team does an excellent job of laying out high-quality and useful numbers about one of the policy interventions that may truly be low-hanging fruit: high-quality universal pre-K.

Read Austin Clemens, Robert Lynch, and Kavya Vaghul’s “A snapshot of the long-term impacts of universal prekindergarten”: “A high-quality universal prekindergarten program … fully phased in by the end of 2017 … would require a total of $78 million in Delaware taxpayer dollars. Over time, the cost would eventually grow to include the cost of additional high school and college attendance. But in just 7 years after full phase-in, by the end of 2023, the benefits of the program would outstrip the costs. And by 2050, there would be more than $1,000 million in total benefits compared to merely $106 million in total costs, yielding net benefits of $893 million. By 2050, for every dollar invested in a universal program, there would be $9.39 in returns.”

Jesse Rothstein’s Challenge to Raj Chetty et al.

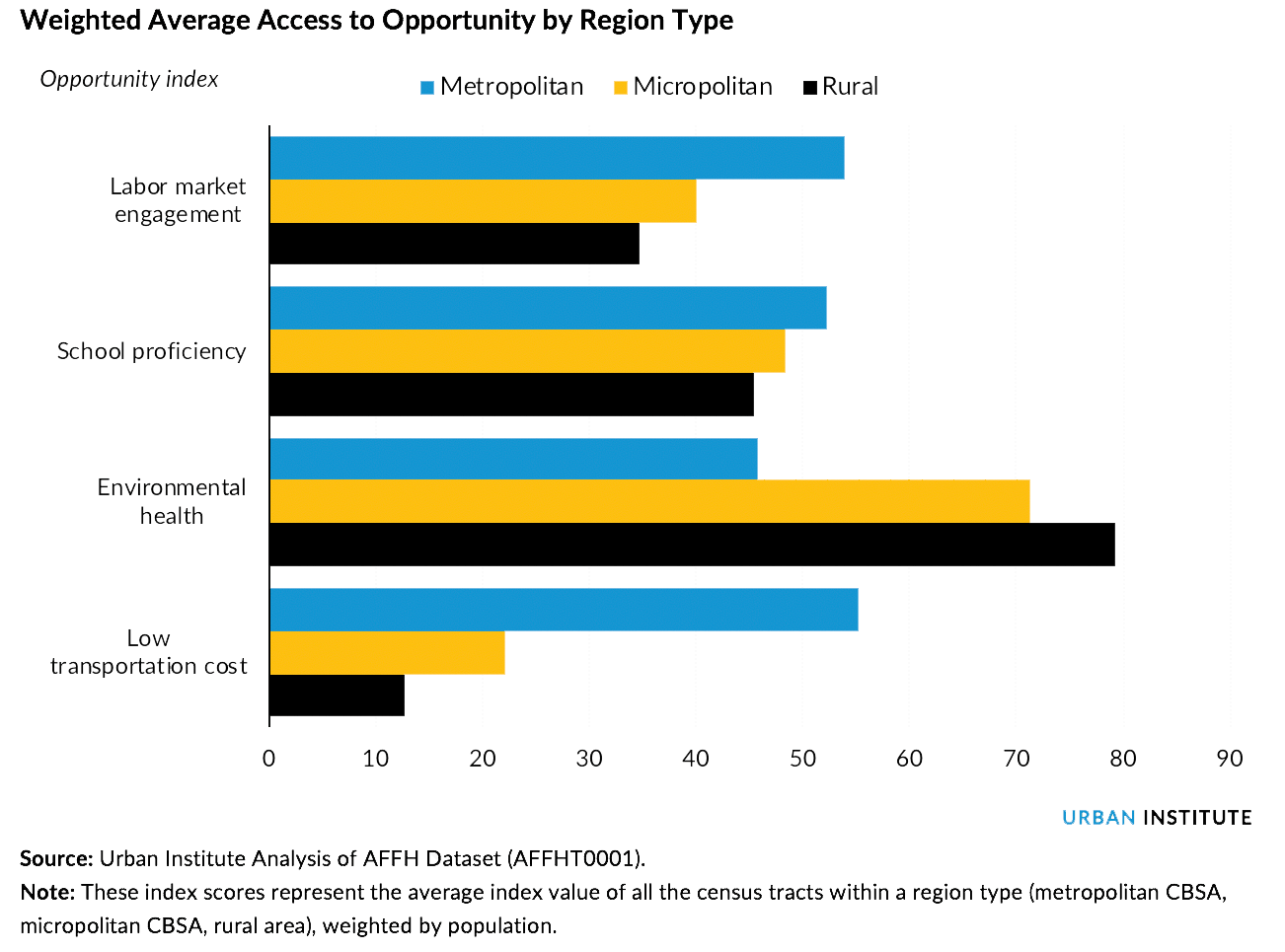

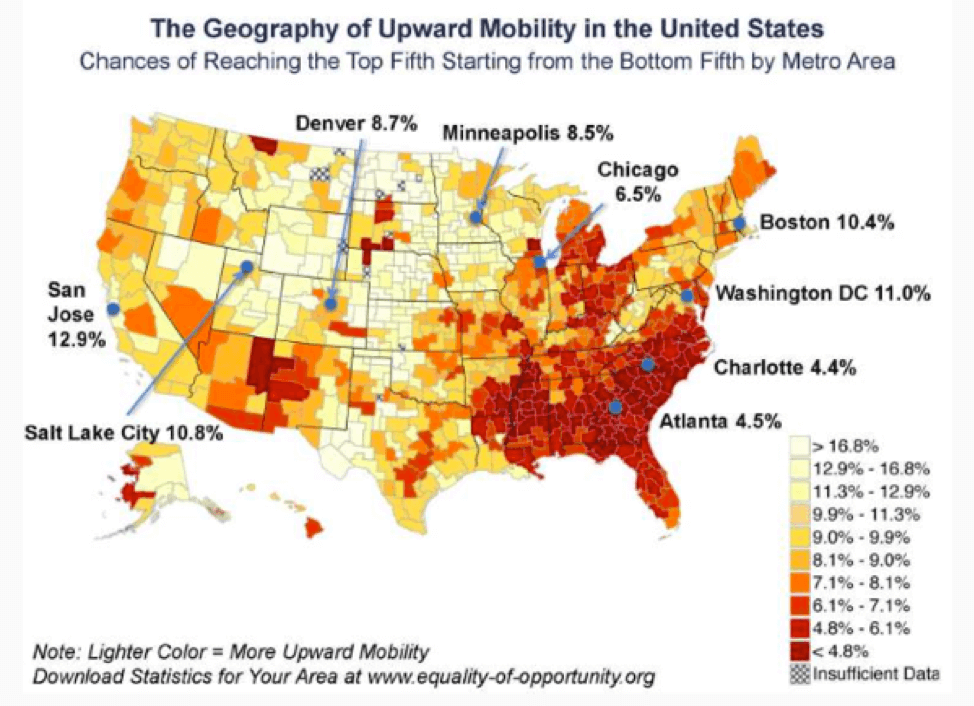

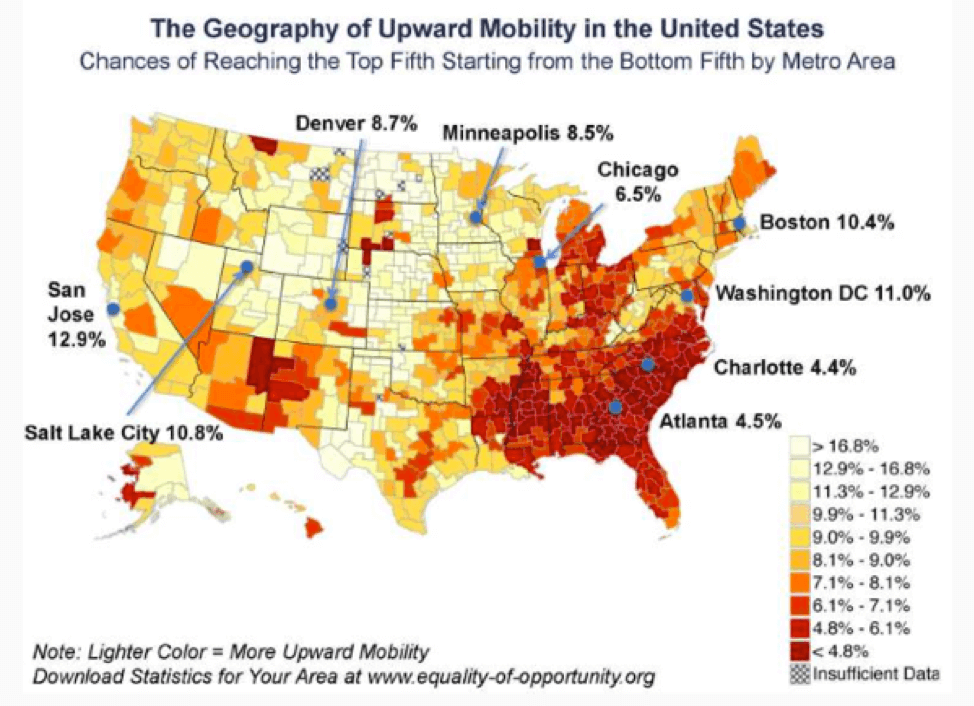

Do we, in fact, have reason to think that removing educational blockages could supercharge social mobility? Stanford University economist (and Equitable Growth Steering Committee member) Raj Chetty and his co-authors say “yes.” University of California, Berkeley economist (and Equitable Growth Research Advisory Board member) Jesse Rothstein says “no.” Chetty et al. believe that we could raise social mobility in the “frozen” regions of the country via effective strategic improvements in education systems—if we could find and implement such effective strategic improvements. Rothstein looks at “job networks … the local labor and marriage markets … as likely factors influencing intergenerational economic mobility.”

I do not have a dog in this fight. I have enormous respect for Chetty, for the rest of his team, and also for Rothstein, who sits two buildings north of my office at the University of California, Berkeley. Looking at Chetty et al.’s maps, you cannot help but be struck by the geographic concentration of low mobility in the large American Indian reservations, in the Civil War confederacy, and in the Ohio-Indiana-Michigan corridor. If the problem’s root was just the poor functioning of one regionally differentiated societal system—schools—would we expect to see such a pattern? The pattern predisposes me to Rothstein: This looks to me like sociology in action, rather than poor policy implementation in the public provision of educational services.

Nudging this kind of debate along is exactly what we should be doing and exactly the kind of thing that we could do well and of which we could do more.

Read Jesse Rothstein’s “Inequality of educational opportunity? Schools as mediators of the intergenerational transmission of income”: “[Do] children’s educational outcomes (educational attainment, test scores, and non-cognitive skills) mediate the relationship between parental and child income[?] Commuting zones (CZs) with stronger intergenerational income transmission tend to have stronger transmission of parental income to children’s educational attainment, as well as higher returns to education. By contrast, the CZ-level association between parental income and children’s test scores is only weakly related to CZ income transmission, and is stable across grades. There is thus little evidence that differences in the quality of K-12 schooling are a key mechanism driving variation in intergenerational mobility. Access to college plays a somewhat larger role, but most of the variation in CZ income mobility reflects (a) differences in marriage patterns … (b) differences in labor market returns to education; and (c) differences in children’s earnings residuals, after controlling for observed skills and the CZ-level return to skill. This points to job networks or the structure of the local labor and marriage markets, rather than the education system, as likely factors influencing intergenerational economic mobility.”

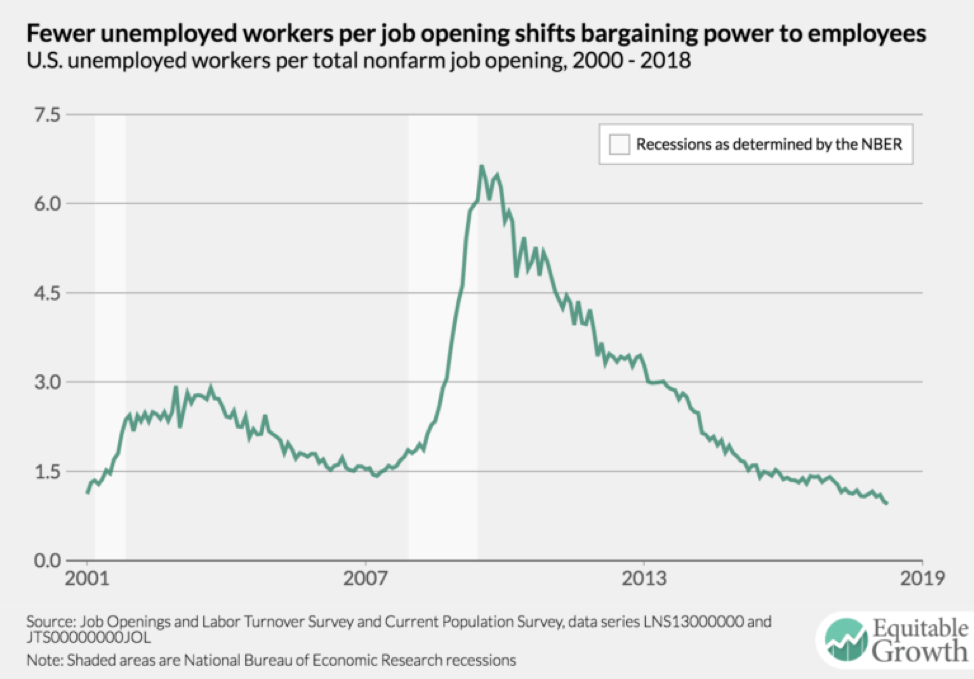

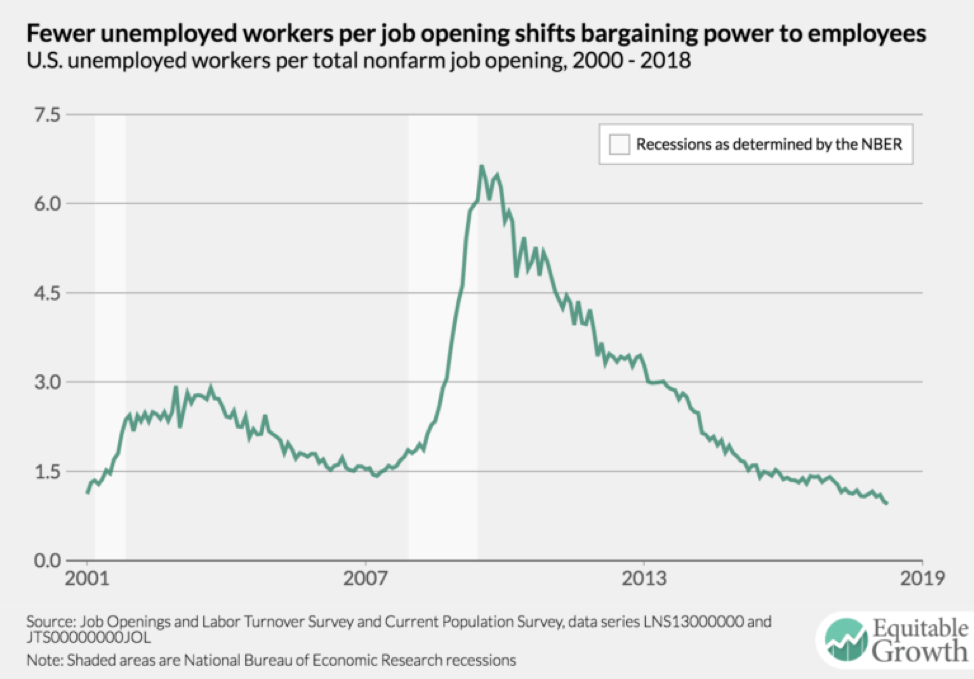

Nick Bunker on JOLTS

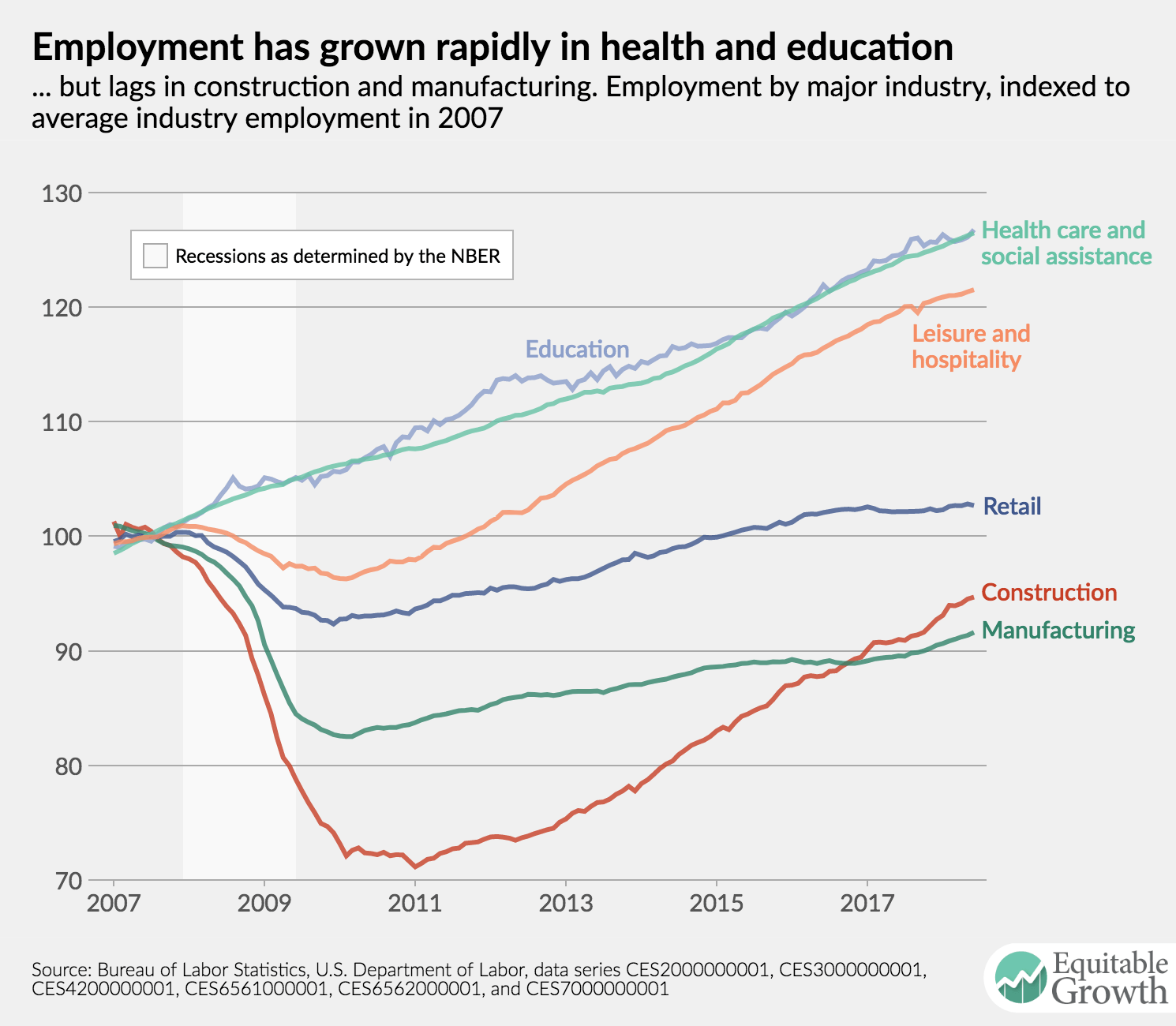

Not a single piece, but rather a series of monthly blog posts, is compiled by Equitable Growth staff under the lead of (now former) Senior Policy Analyst Nick Bunker on JOLTS—the Job Opportunity and Labor Turnover dataset released monthly by the U.S. Department of Labor. The U.S. press produces a huge amount of coverage and analysis—most of it of very low quality, but we are not going there right now—about the changing monthly, nay daily, state of finance and profits. But there is very little that is regular and timely about changes in the state of the labor market. Nick Bunker’s series on JOLTS has been doing a superb job, and I look forward to this important work continuing under Equitable Growth Economist Kate Bahn.

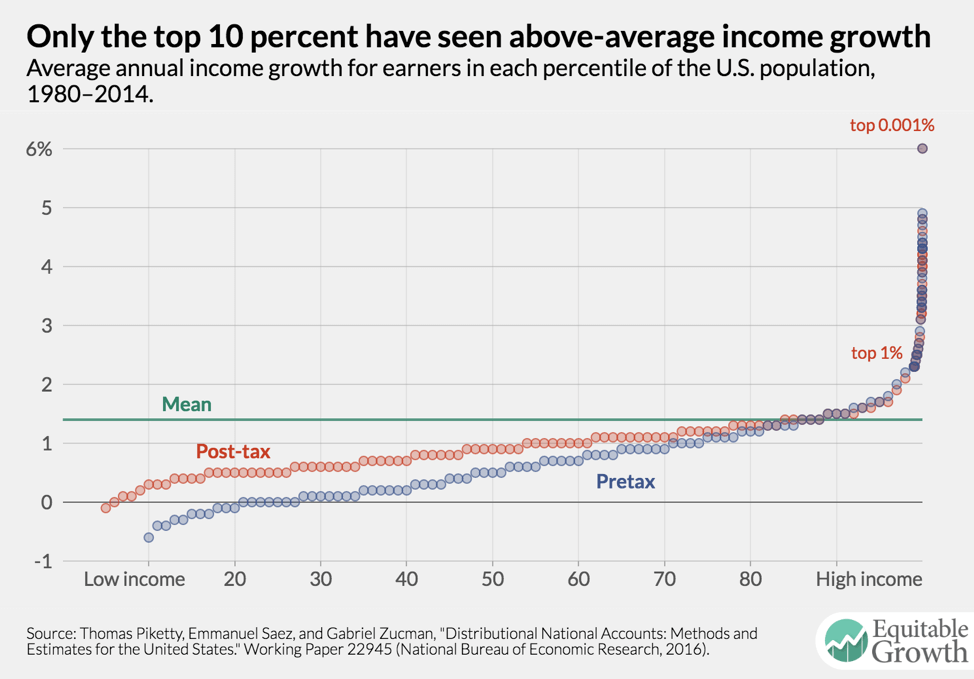

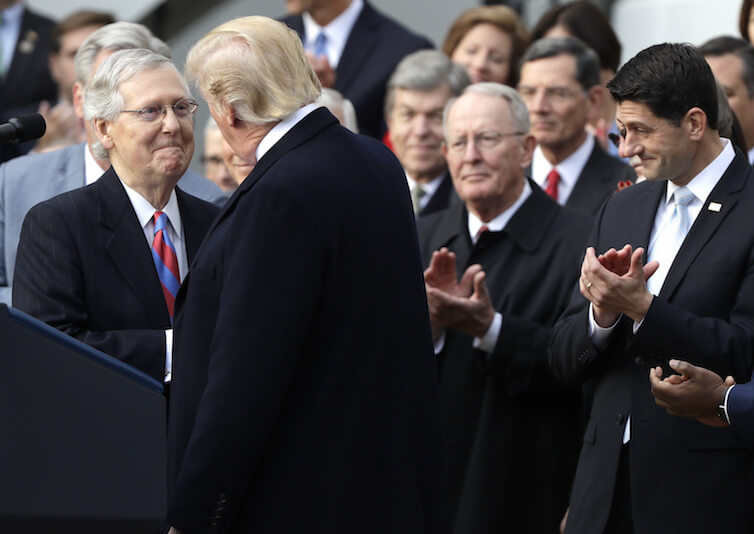

Greg Leiserson on the December 2017 tax bill

One of the greatest headwinds facing the equitable growth project is low-quality analyses by high-profile people who definitely know better. Consider the public-sphere discussion of President Donald Trump’s and the congressional Republicans’ tax cut bill in the fall of 2017. This led, for example, to an anguished rant by the very sharp reporter Binyamin Applebaum of The New York Times on Twitter about the state of the economics discipline.

Read Binyamin Applebaum: “I am not sure there is a defensible case for the discipline … if they can’t at least agree on the ground rules for evaluating tax policy. How does Harvard, for example, justify granting tenure to people who purport to work in the same discipline and publicly condemn each other as charlatans? What does it mean to produce the signatures of 100 economists in favor of a given proposition when another 100 will sign their names to the opposite statement? … How are ordinary people, let alone members of Congress, supposed to figure out which tenured professors are the serious economists?”

Well, we professional economists briefed up on the issue know that, say, Doug Holtz-Eakin, Charles Calomiris, Jim Miller, Jagdish Bhagwati, and a hundred-odd other economists’ claims that the tax cut would come close to paying for itself via the extra tax revenues from faster economic growth were worthless. As Columbia University economist Bhagwati then stated, “I agree with the main thrust of the letter but do not think it likely that tax cuts will produce revenues that offset the initial loss of revenue.” (No, I do not understand how Bhagwati can disagree with the principal claim of a letter, yet agree with its “main thrust.” No, I do not understand why anybody would sign a letter and then state that they disagreed with its principal claim.) We professional economists briefed up on the issue know that Harvard University economist Robert Barro simply should not have claimed that the tax cut would ultimately boost real GDP above its projected baseline path by 7 percent.

But what should Binyamin Applebaum and others do? They should follow, and trust, Greg Leiserson on the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. He has been on fire in both performing the most sophisticated and accurate analyses and explaining his point of view clearly. I am extremely proud that his work on this has appeared at Equitable Growth on its tax pages.

Our engagement with Thomas Piketty’s Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century

After Piketty: The Agenda for Economics and Inequality has not, in my estimation at least, received the attention it deserves. But it is of very high quality indeed. For example:

- Brad DeLong, Heather Boushey, and Marshall Steinbaum: ““Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” Three Years Later”

- My 2014 “Mr. Piketty and the “Neoclassicists”: A Suggested Interpretation.” It still provides the best guide to understanding Piketty’s “compare r to g.” That was a shortcut that, I think, caused considerable confusion. If you want to sort those issues out, I am your guide.

- Equitable Growth, in conjunction with the City University of New York, ran the best panel on what the takeaways from and research agenda after Piketty are: “A Few Notes on the CUNY “After Piketty” Panel.”

- Worth reading is my extension of Laura Tyson and Mike Spence’s contribution to our After Piketty book in the light of Ryan Avent’s very interesting The Wealth of Humans: “Fifteen Theses on “The Wealth of Humans” and “After Piketty”

Getting the analysis of Piketty right is, I think, important if the global public sphere is to have a productive conversation about equitable growth issues over the next decade. And it is important because, at least as I see it, an awful lot of Piketty criticism was in bad faith. Let Ryan Avent’s comments on one critic stand in for the evaluation of an entire portfolio: “Why, for instance, doesn’t Mr. Piketty say that r must be significantly above g to generate the expected divergence, Mr. Crook complains. This, after literally hundreds of pages in which Mr. Piketty has walked through when and how the capital-income ratio has been pushed away from its long-run trend rate. You don’t even have to read hundreds of pages to get the qualification Mr. Crook wants; you can start with the page on which r > g is first mentioned: “If, moreover, the rate of return on capital remains significantly above the growth rate for an extended period of time (which is more likely when the growth rate is low, though not automatic), then the risk of divergence in the distribution of wealth is very high.” … I suppose if you only read the book’s conclusion you could miss these details, but who would do that?”

We can do better as a society. We need to do better. And I think Equitable Growth is doing better. I think we are, in fact, accomplishing our mission—not just in our writing of mission statements, but also where the rubber meets the road.