This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is the work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

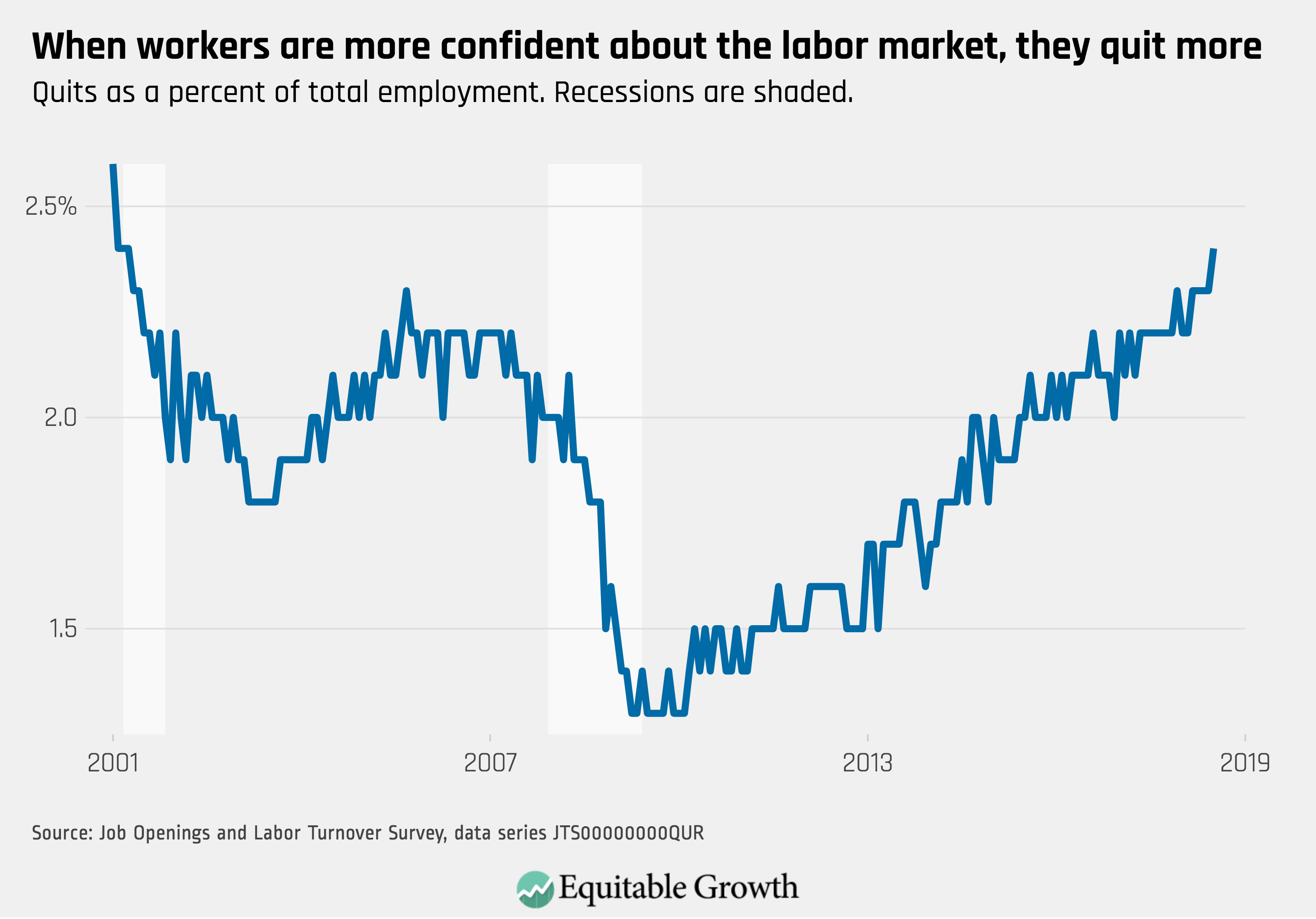

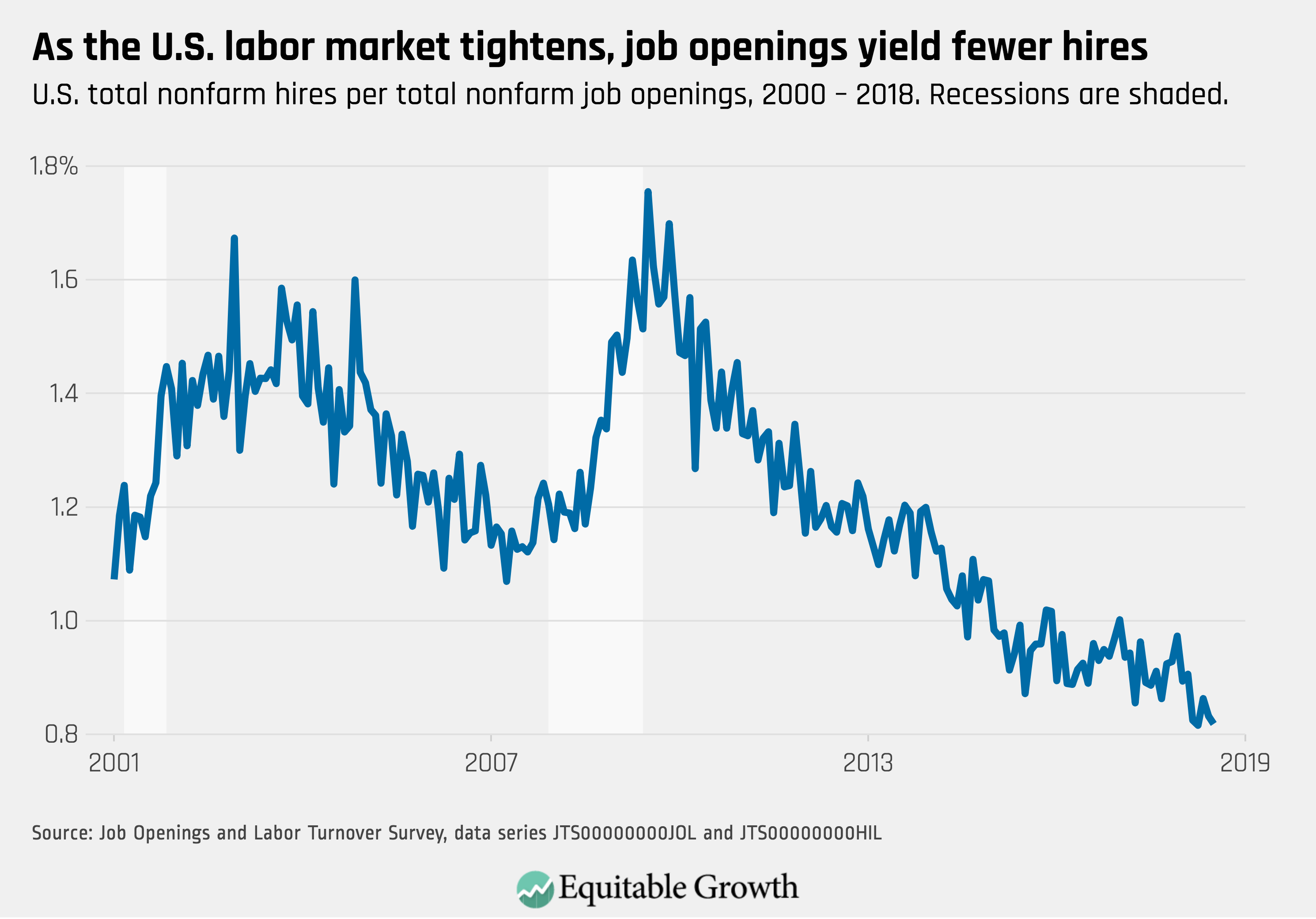

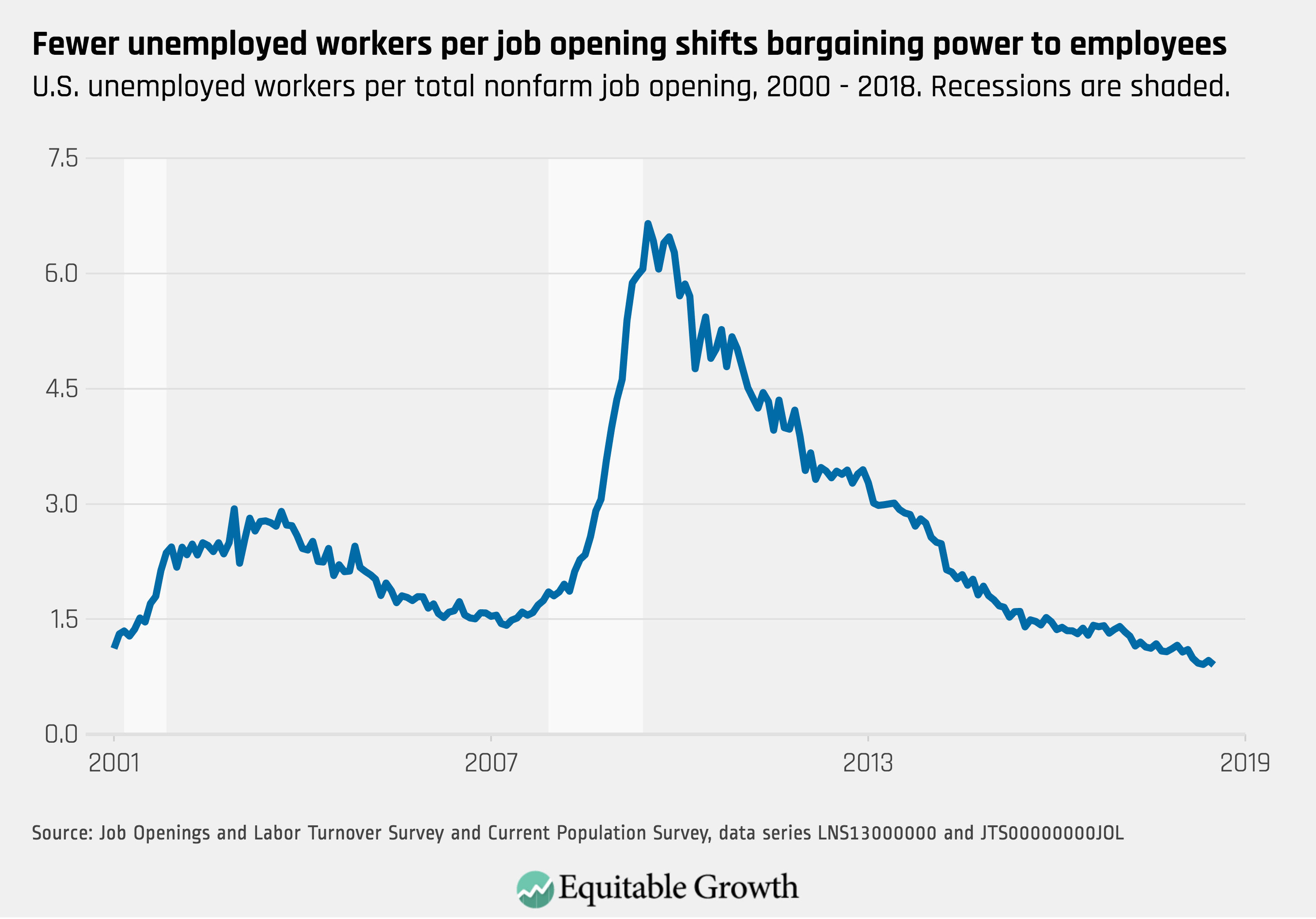

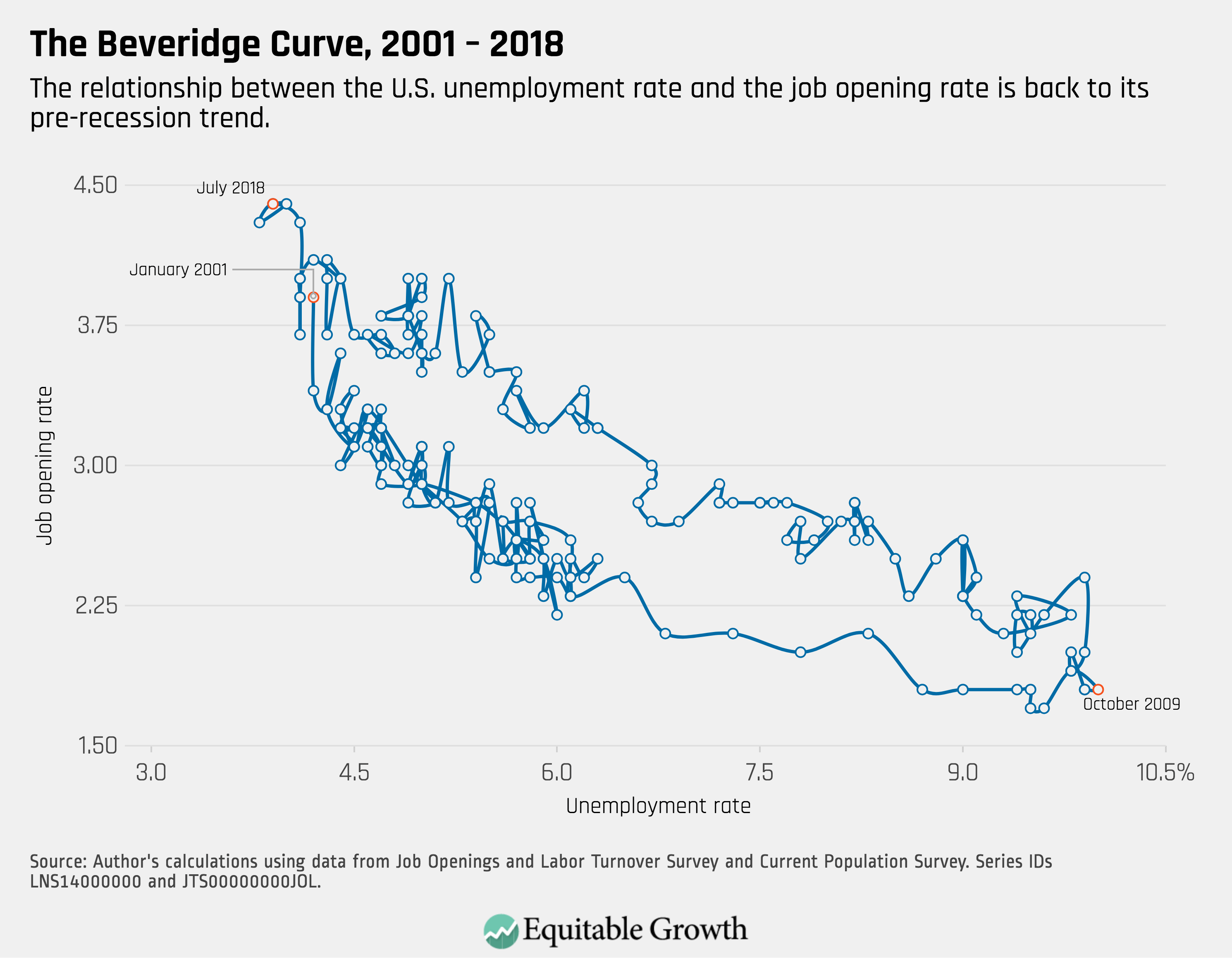

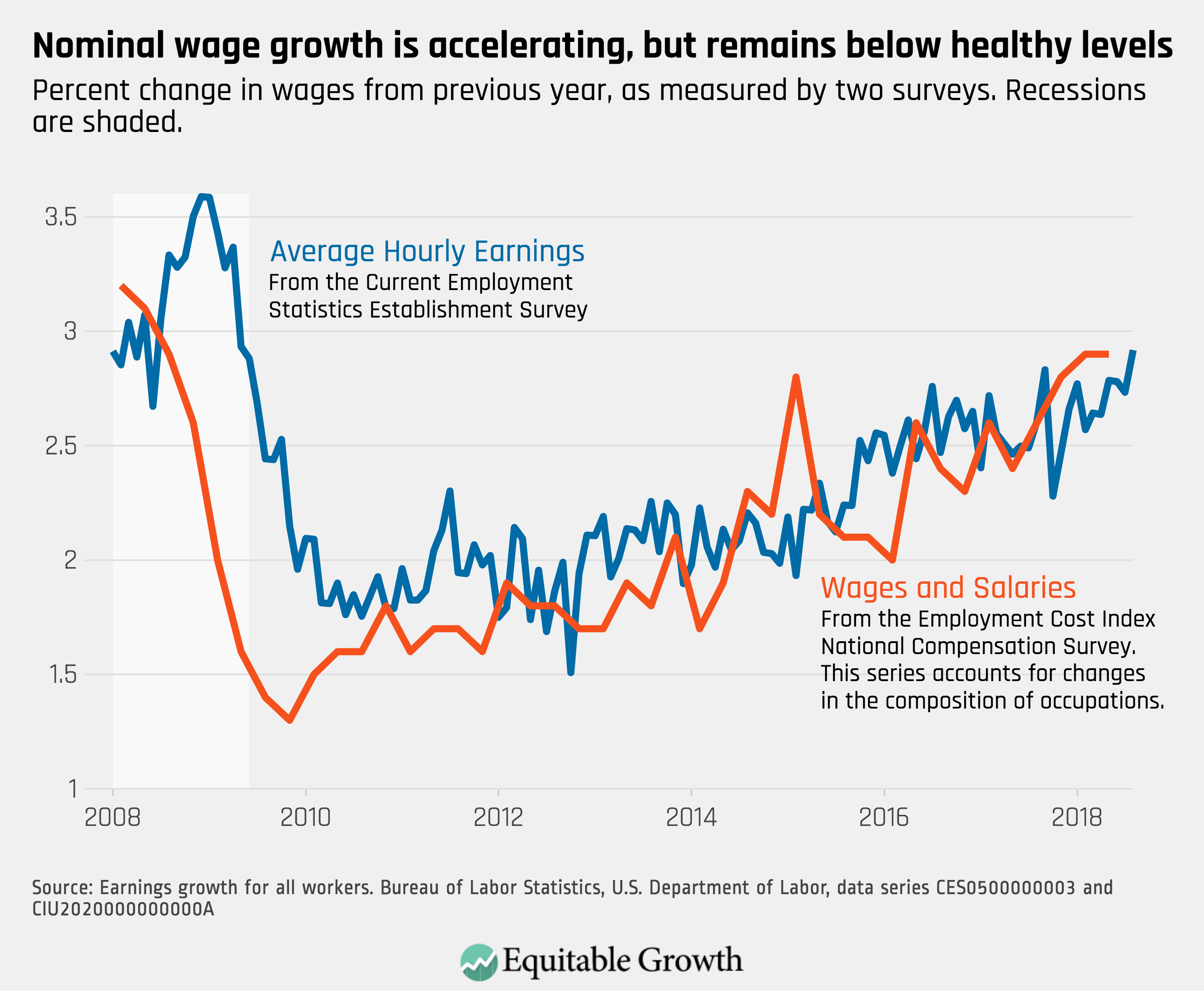

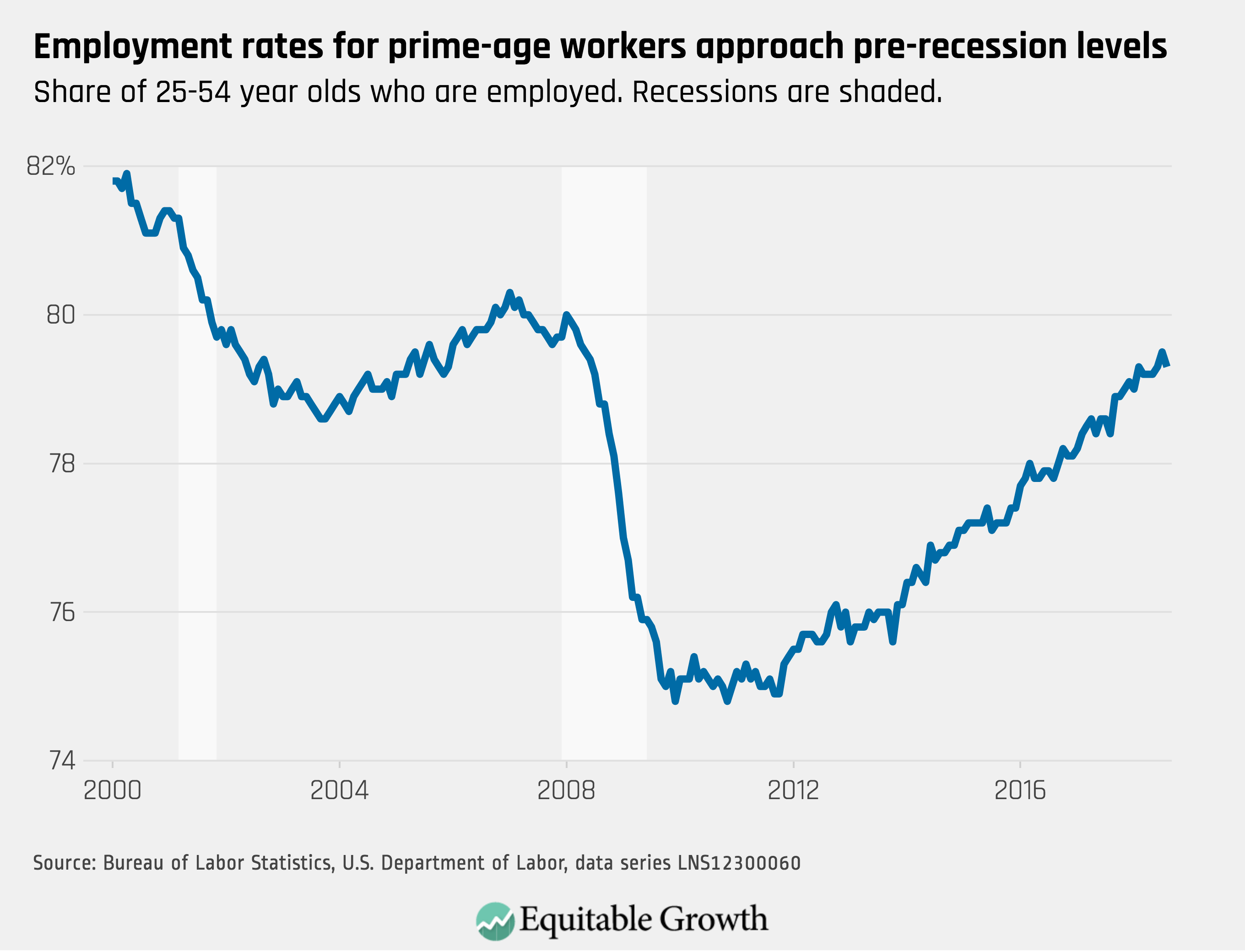

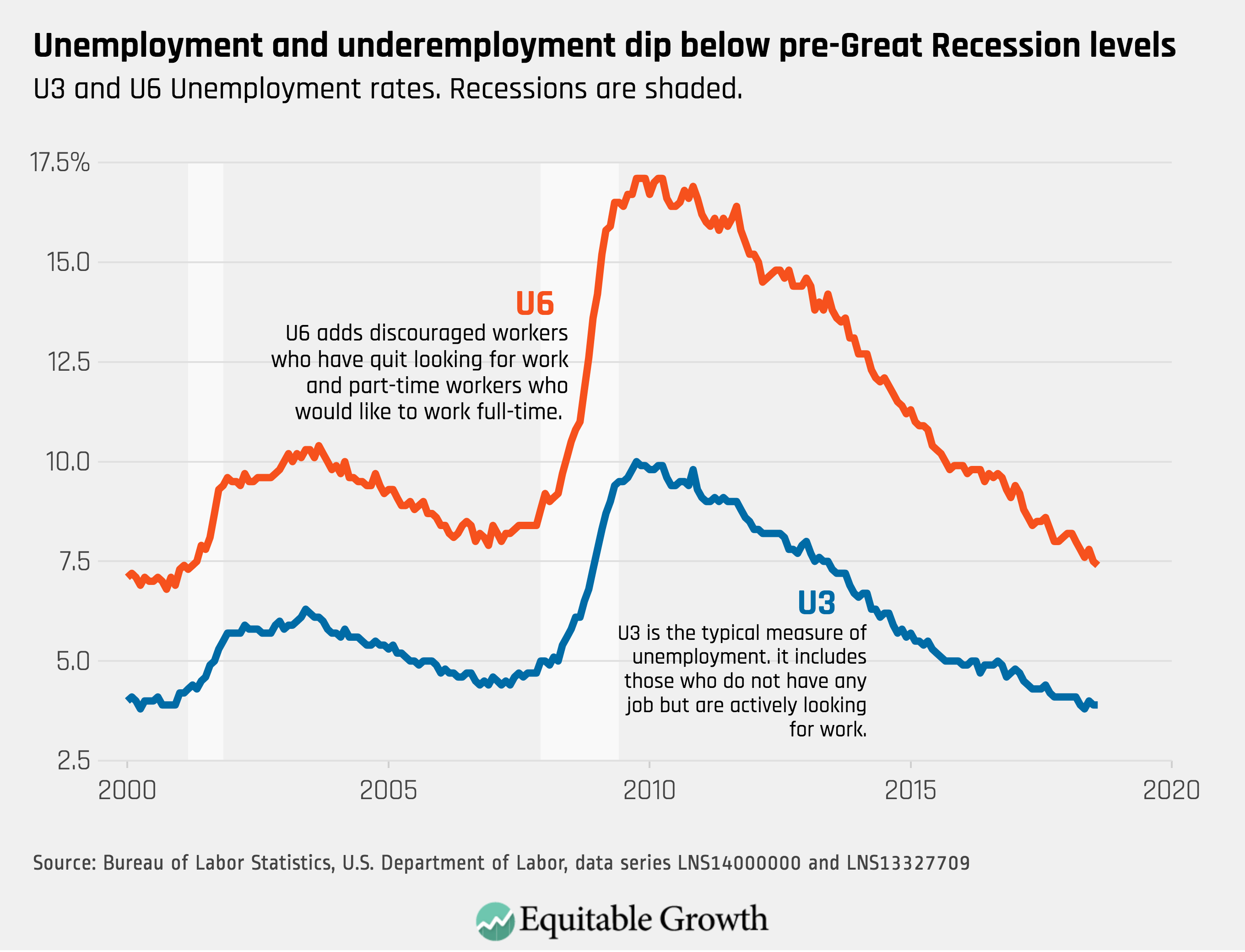

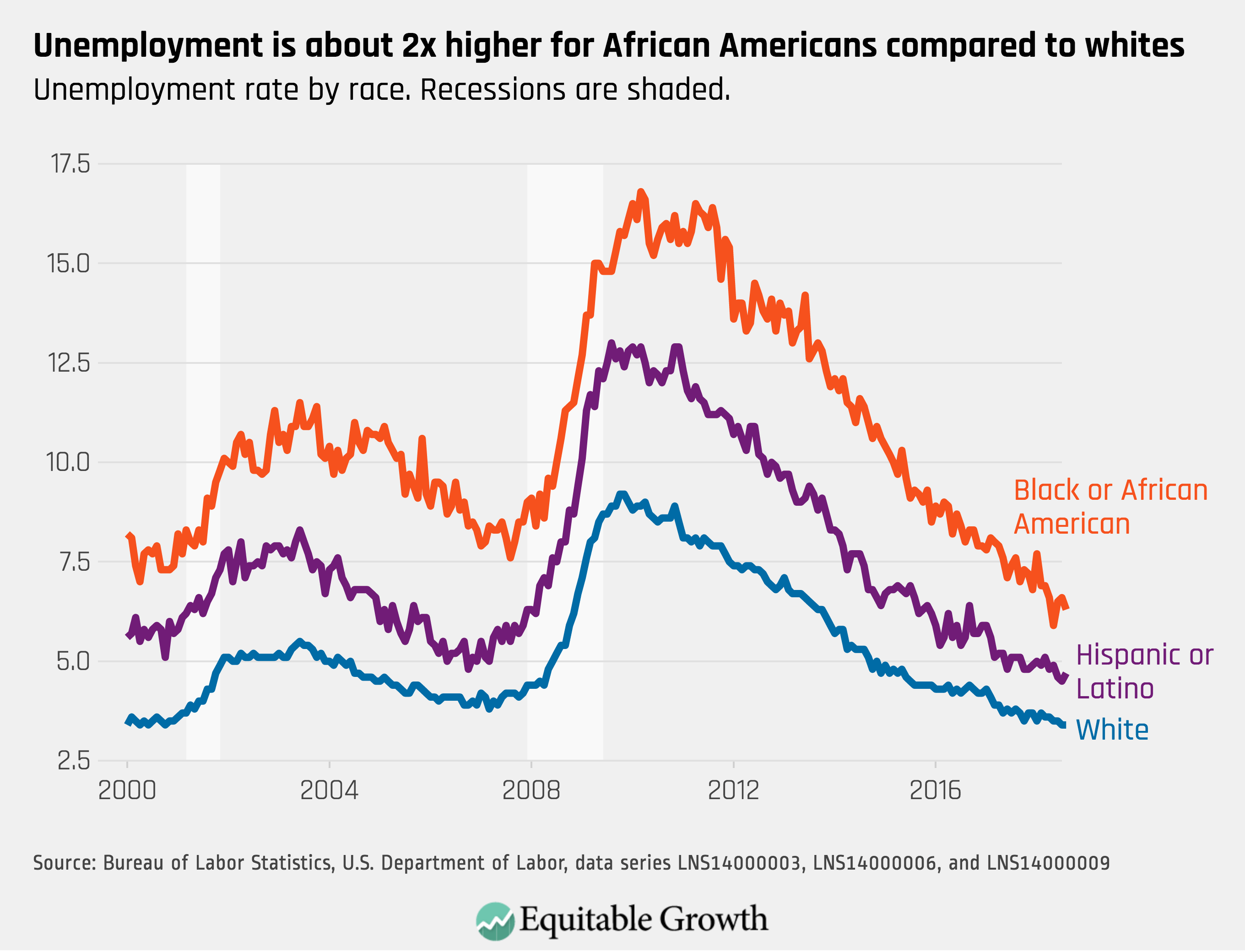

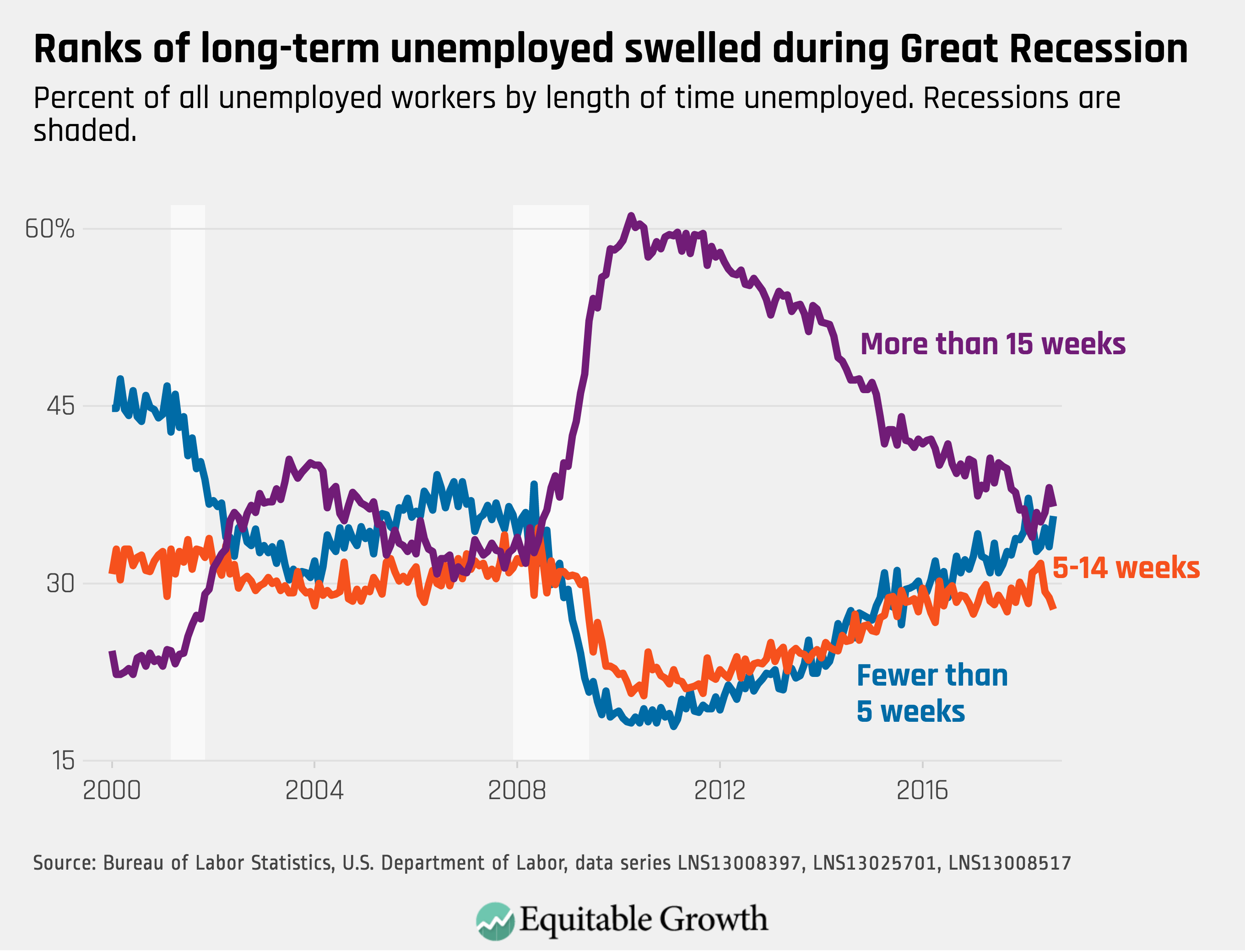

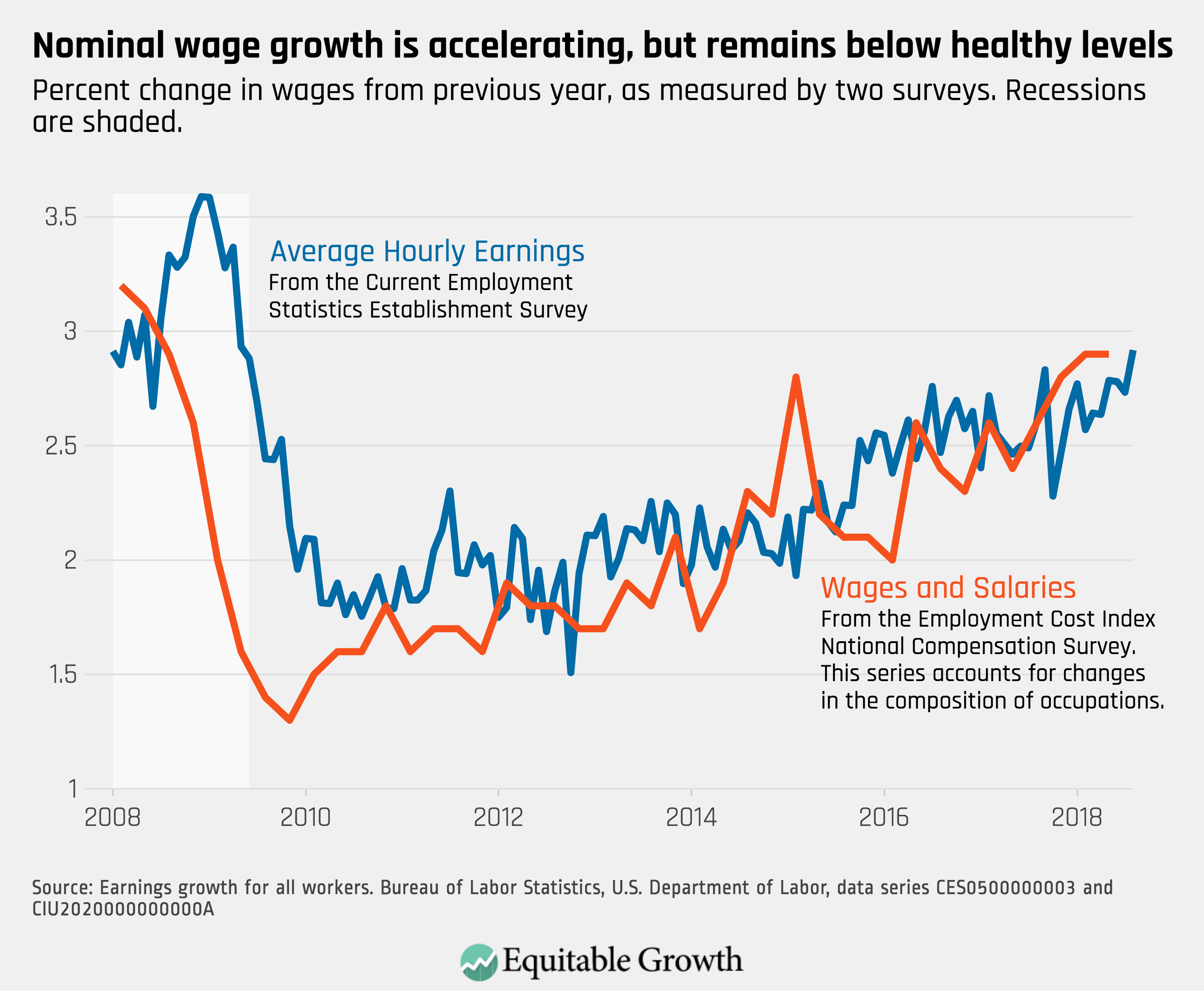

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics on Friday released new data on the U.S. labor market during the month of June. Kate Bahn and Austin Clemens put together five graphs highlighting important trends in the data.

Brad DeLong compiles his most recent worthy reads on equitable growth both from Equitable Growth and outside press and academics.

Peter Ganong and Pascal Noel studied the outcomes for distressed mortgage borrowers of reducing principle owed or monthly payments. Using regression discontinuity and difference-in-difference designs to measure default rates and consumption, they find that reducing principle owed had no effect on default or consumption rates, whereas reducing monthly payments had widespread positive effects on default rates. This suggests that access to financial liquidity plays a larger role in borrowers’ financial decision-making than total debt or net wealth.

A new study published by the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment at the University of California, Berkeley explains the effects of gradually increasing the minimum wage to $15 as displayed by many urban cities across the United States. The authors, economists and Equitable Growth grantees Sylvia Allegretto, Anna Godoey, Carl Nadler, and Michael Reich, find that a 10 percent increase in the minimum wage results in an earnings increase of 1.3 percent to 2.5 percent among low-wage jobs. In addition, the 10 percent increase has an ambiguous effect on employment, ranging between a 0.3 percent decrease to a 1.1 percent increase in employment. Here is a summary of the study and related Equitable Growth research on the topic of minimum wage.

Links from around the web

The Affordable Care Act’s bundle-payments program, in which the government pays hospitals a single amount for each category of surgery rather for individual procedures, lowered the costs per procedure and increased the quality of care that patients received. This program has the potential to save patients thousands of dollars, thus making these procedures more affordable and accessible to low-income patients. [vox]

After experiencing hardships and cutbacks during the Great Recession of 2007-2009, Generation Z is now entering the workforce determined to experience wealth, economic mobility, and financial security. Driven by the idea of financial stability and growth, members of this generation born in the 1990s have prioritized their education and their careers over social factors such as drinking and partying. They have made financial decisions that benefit their long-term monetary and career goals, such as decreasing the amount of student loans taken on and choosing less-expensive colleges to attend. Gen Z also is the most diverse population of students and workers, indicating a future growth of ethnic and racial minorities in the workforce. [wsj]

Similar to the United States, Nordic countries such as Denmark, Finland, and Sweden have experienced declines in unionization since the 1990s, yet the overall union membership rate is still 41.7 percent to 56.9 percent higher than U.S. rates. Between 84 percent to 90 percent of Nordic workers have collective bargaining coverage, which is roughly 72 percent to 78 percent higher than U.S rates. Denmark, Finland, and Sweden—so called “Ghent system” countries that have a union structure with the dual priority of preserving employment and competitiveness—believe in the economic benefits of outsourcing jobs, especially the aspect of establishing these countries as competitive in the global markets. Thus, unions in these nations provide generous unemployment benefits subsidized by the government to incentivize union membership. Conservative fans of the Ghent system in the United States advocate for unions to increase services and trainings for members rather than promoting collective bargaining practices as a means of creating a more competitive workforce. [bloomberg]

Occupations that don’t require college degrees, such as food manufacturing and maintenance, used to pay above-average wages in the 1990s, but new data shows that these professions pay far less than average wages today. These jobs used to provide workers with only a high-school education a path to the middle class, yet this new data indicates that well-paying jobs require higher education and training not available to low or middle-class workers. [wapo]

Social mobility is largely determined by parents’ profession, which has contributed to a decline in American children who out-earn their parents. Michael Hout, a professor at New York University, finds that mobility between generations shrank by 15 percent between those born in 1945 and 1985. Massive structural changes in the U.S. economy, especially with the transition from an industrialized economy to a service-based one, means that growth in white-collar, high-wage jobs rapidly increased for those born in the 1940s. Successive generations saw the consolidation of wage growth among upper class families, thus increasing the difficulty of children out-earning their parents. [wsj]

Friday figure

Figure is from “Equitable Growth’s Jobs Day Graphs: August 2018 Report Edition.”