Today was the final day of the three-day annual meeting of the Allied Social Science Associations, which is organized by the American Economic Association. The conference, held in San Diego this year, featured hundreds of sessions covering a wide variety of economics and other social science research. We’ve already posted the abstracts of some of the papers that caught the attention of Equitable Growth Staff during Day One and Day Two, as well as links to the sessions at which they were presented. Following are additional papers from the first two days as well as some from today’s final slate of sessions and an important report from AEA.

AEA Professional Climate Survey: Final Report

American Economic Association Committee on Equity, Diversity and Professional Conduct

Introduction: In April 2018, the Ad Hoc Committee on the Professional Climate in Economics recommended that the AEA conduct a professional climate survey to assess the status quo in the profession, and repeat this survey at regular intervals to monitor changes over time. The AEA charged a new standing committee, the Committee on Equity, Diversity and Professional Conduct, to carry out this work.

A survey was designed to gather critical information about the professional climate in economics, with particular focus on aspects that limit inclusiveness, demean and/or harass individuals, or otherwise engender incivility in work environments. The survey was sent to all current members of the AEA (as of December 2018) as well as all individuals who had been AEA members at any point in the prior 9 years.

This report summarizes the Committee’s work. The report is organized as follows. In Section 1, we describe the survey methodology, survey population and response rate, and data collection procedures; we also include a discussion of possible survey response bias. Section 2 summarizes the main findings of the survey in a set of tables. Among other things, we report on the perception of the overall climate in economics, experiences of discrimination in and outside of academia, behavioral changes to avoid discrimination and unfair treatment, and experiences of exclusion and harassment. Section 3 provides brief descriptions of the key findings along the following dimensions: gender, race and ethnicity, LGBT status, disability, ideology and religion; whenever possible, we use comments provided by survey respondents to provide concrete examples of the experiences of, and concerns raised by, members of the Association. Section 4 highlights some of the patterns of responses to an open-ended question on the climate within the profession and attempts to summarize some of the most commonly expressed views. These views include frequent references to the elitism of the field of economics, a dimension of the climate the survey instrument did not otherwise cover. Finally, Section 5 offers comparisons of some of the survey results to those obtained in similar climate surveys carried out by other professional associations.

Corporate Tax Cuts and the Decline of the Manufacturing Labor Share

Baris Kaymak, University of Montreal, and Immo Schott, University of Montreal

Abstract: We document a strong empirical connection between corporate taxation and the manufacturing labor share across OECD countries as well as across U.S. states. Our estimates associate 30% of the observed decline in the labor share with the global fall in corporate taxation. We present an equilibrium model of an industry where firms differ in their capital intensities. Lower corporate tax rates reduce the labor share by raising the market share of capital intensive firms. The tax elasticity of the aggregate labor share depends on the distribution of labor intensities at the micro level. Given the observed distribution of factor intensities in the U.S. manufacturing industry, the model predicts that corporate tax cuts explain about 40% of the decline in the manufacturing labor share since the 1950s.

Do Wage-setting Shocks Propagate Across Firms? Evidence from Employer Minimum Wage Increases

Ellora Derenoncourt, Princeton University, David Weil, Brandeis University, and Clemens Noelke, Brandeis University

Abstract: Low unionization rates, a falling real federal minimum wage, and prevalent non-competes characterize the low-wage sector in the United States and contribute to growing inequality. In recent years, a number of private employers in the U.S. have opted to institute or raise company-wide minimum wages for their employees, sometimes in response to public pressure. To what extent do these policy changes at major employers spill over to other employers in a local labor market? This paper examines spillover effects of recent company minimum wage increases, including Amazon’s recent increase to $15 an hour in 2019 and Walmart to $9 an hour in 2015. We estimate the impact of these policies on other low-wage employers in the same county using data on minimum posted wages from online job ads. We find large spillover effects from both Amazon’s 2019 and Walmart’s 2015 increases. We discuss potential mechanisms and plans to extend the analysis to over 100 recent employer minimum wage increases across the U.S.

“The Educational Progress of United States-Born Mexican Americans”

Stephen Trejo, University of Texas at Austin, and Brian Duncan, University of Colorado Denver

Abstract: Using microdata from the decennial U.S. Censuses of 1970-2000 and the American Community Survey from 2006 forward, we track changes in the educational attainment U.S.-born Mexican Americans over seven decades. We compare the schooling gains of Mexican Americans with the corresponding gains made by African Americans and by non-Hispanic whites. Our analyses produce several important findings. First, Mexican Americans have experienced enormous gains and have closed most of their large initial schooling deficit relative to non-Hispanic whites and all of their deficit relative to African Americans. Second, progress for Mexican Americans has been greatest in the lower tail of the schooling distribution. For many years, rates of high school completion were dramatically lower for Mexican Americans than for other Americans, but this gap is much smaller for recent birth cohorts. In contrast, although rates of college enrollment and college completion have been rising for Mexican Americans, these rates still fall far short of the corresponding rates for non-Hispanic whites. Finally, the initial schooling deficits and subsequent gains of Mexican Americans vary with their state of birth. These geographic differences suggest the potential importance of state-specific policies and institutions for shaping the educational progress of Mexican Americans.

“Killer Acquisitions”

Colleen Cunningham, London Business School, Florian Ederer, Yale University, and Song Ma, Yale University

Abstract: This paper argues incumbent firms may acquire innovative targets solely to discontinue the target’s innovation projects and preempt future competition. We call such acquisitions “killer acquisitions.” We develop a parsimonious model illustrating this phenomenon. Using pharmaceutical industry data, we show that acquired drug projects are less likely to be developed when they overlap with the acquirer’s existing product portfolio, especially when the acquirer’s market power is large due to weak competition or distant patent expiration. Conservative estimates indicate about 6% of acquisitions in our sample are killer acquisitions. These acquisitions disproportionately occur just below thresholds for antitrust scrutiny.

The Labor Market Effects of Immigration Enforcement

Chloe N. East, University of Colorado-Denver, Annie Hines, University of California, Davis, Philip Luck, University of Colorado Denver, Hani Mansour, University of Colorado Denver, and Andrea Velasquez, University of Colorado Denver

Abstract: We examine the labor market effects of Secure Communities (SC)–an immigration enforcement policy which led to over 454,000 deportations between 2008-2015. Using a difference-in-differences model that takes advantage of the staggered rollout of SC, we find that SC significantly decreased the employment share of likely undocumented male immigrants. Importantly, the policy also led to a decrease in the employment rate of citizens. The employment effects are concentrated among male citizens working in higher-skilled occupations, particularly in sectors that traditionally rely on likely undocumented workers. This is consistent with complementarities in production between low-skilled immigrants and higher-skilled citizens.

Outside Options in the Labor Market

Sydnee Caldwell, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Oren Danieli, Harvard University

Abstract: This paper develops a method to estimate the employment opportunities available to each worker, and to assess the impact of these outside options on the gender wage gap. We outline a matching model with two-sided heterogeneity, from which we derive a sufficient statistic, the “outside options index” (OOI), that captures the effect of outside options on wages, holding productivity constant. This OOI uses the cross-sectional concentration of similar workers across job types to quantify the availability of outside options as a function of workers’ commuting or moving costs, preferences, and skills. Higher concentration in a narrower range of job types implies lower OOI and higher dispersion across a wide variety of job types means higher OOI. We use administrative data to estimate the OOI for every worker in a representative sample of the German workforce. We estimate the elasticity between the OOI and wages using two sources of quasi-random variation in the OOI, that holds workers’ productivity constant: the introduction of high-speed commuter rail stations, and a shift-share (“Bartik”) instrument. Using this elasticity and the observed distribution of options, we find that differences in options explain 30% of the gender wage gap. The differences in (similarly skilled) men and women’s option sets are driven primarily by differences in the implicit costs of commuting and moving.

“’Prep School for Poor Kids’: The Long-Run Impact of Head Start on Human Capital and Productivity”

Martha Bailey, University of Michigan, Shuqiao Sun, University of Michigan, and Brenden Timpe, University of Michigan

This paper evaluates the long-run effects of Head Start using large-scale, restricted 2000-2013 Census-ACS data linked to date and place of birth in the SSA’s Numident file. Using the county-level rollout of Head Start between 1965 and 1980 and state age-eligibility cutoffs for school entry, we find that participation in Head Start is associated with increases in adult human capital and economic self-sufficiency, including a 0.29-year increase in schooling, a 2.1-percent increase in high-school completion, an 8.7-percent increase in college enrollment, and a 19-percent increase in college completion. These estimates imply sizable, long-term returns to investing in large-scale preschool programs.

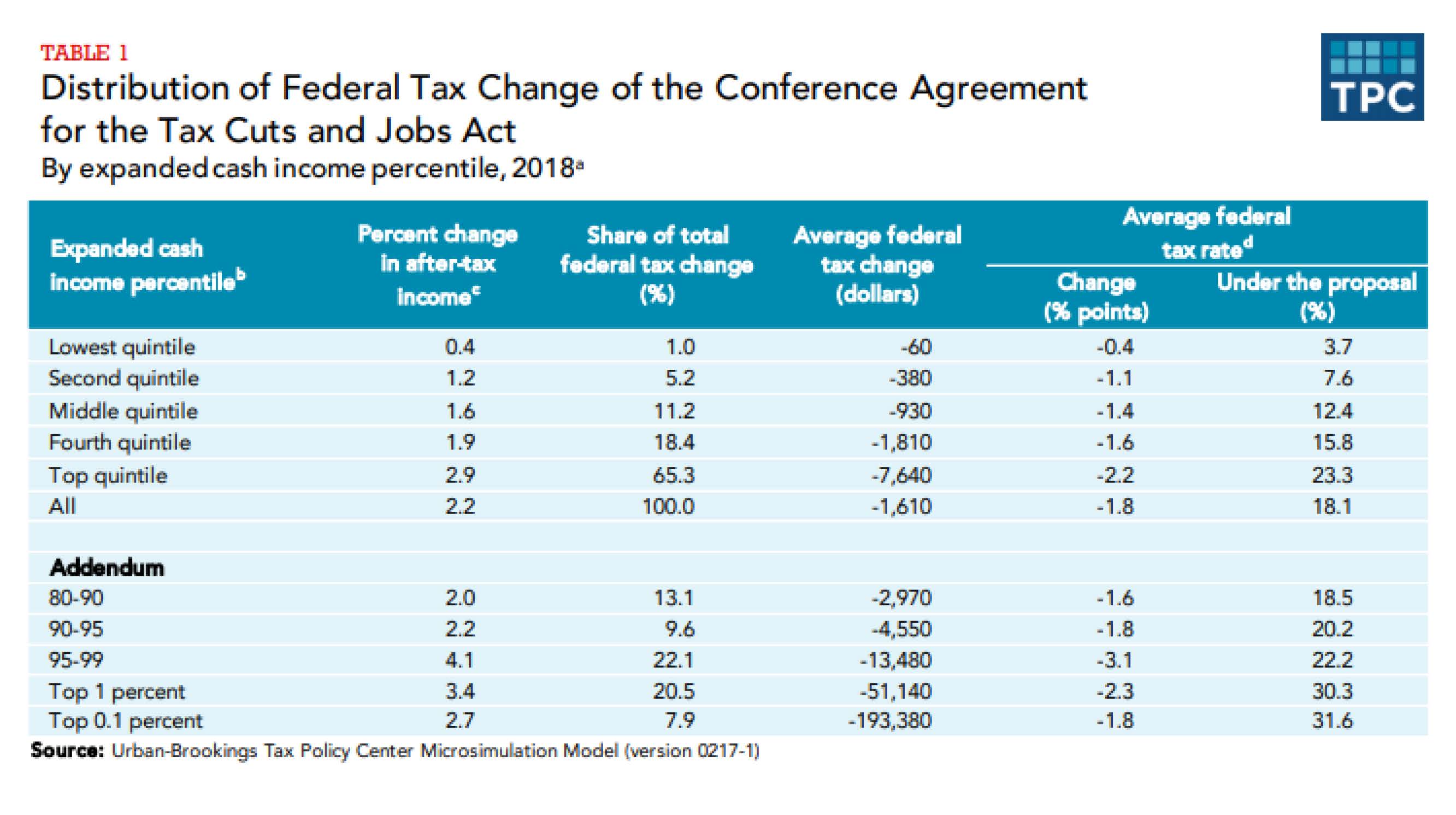

Sharing the Burden: Responses of Business Owners to Changes in the Top Personal Income Tax Rate

Max Risch, University of Michigan

Abstract: This paper analyzes the role of the firm in mediating responses to changes in top marginal tax rates using a new linked owner-firm-employee dataset created from the universe of deidentified administrative tax records from the IRS. The majority of business income in the United States is held by pass-through businesses whose income is taxed at the personal income tax rates of firm owners, as opposed to being taxed at the corporate level. I study whether changes in the top marginal tax rate faced by business owners affect the compensation of the employees in their firms. I use panel difference-in-differences methods to estimate the sign and magnitude of these within-firm spillovers by comparing the earnings of employees in similar firms but whose owners were differentially exposed to a recent increase in the top marginal income tax rate. I find that employees in firms whose owners were more exposed to a tax increase reported lower relative earnings following the tax reform; approximately 18 cents per dollar of new tax liability was passed through to employee earnings. The observed response was a result of lower earnings paid to employees attached to their firms, and not due to compositional changes in employment. The earnings responses were larger in states with slack labor markets and larger among employees in the lower portion of their firms’ earnings distribution. These results provide some of the first direct evidence of pass-through from changes in the top marginal personal income tax rate to lower-bracket workers not directly subject to the top rate. I show that the presence of within-firm spillovers implies that the elasticity of taxable income of those facing a given rate change is not a sufficient statistic for welfare analysis.

Taxation and Innovation in the 20th Century

Stefanie Stantcheva, Harvard University

Abstract: This paper studies the effect of corporate and personal taxes on innovation in the United States over the twentieth century. We use three new datasets: a panel of the universe of inventors who patent since 1920; a dataset of the employment, location and patents of firms active in R&D since 1921; and a historical state-level corporate tax database since 1900, which we link to an existing database on state-level personal income taxes. Our analysis focuses on the impact of taxes on individual inventors and firms (the micro level) and on states over time (the macro level). We propose several identification strategies, all of which yield consistent results: i) OLS with fixed effects, including inventor and state-times-year fixed effects, which make use of differences between tax brackets within a state-year cell and which absorb heterogeneity and contemporaneous changes in economic conditions; ii) an instrumental variable approach, which predicts changes in an individual or firm’s total tax rate with changes in the federal tax rate only; iii) event studies, synthetic cohort case studies, and a border county strategy, which exploits tax variation across neighboring counties in different states. We find that taxes matter for innovation: higher personal and corporate income taxes negatively affect the quantity and quality of inventive activity and shift its location at the macro and micro levels. At the macro level, cross-state spillovers or business-stealing from one state to another are important, but do not account for all of the effect. Agglomeration effects from local innovation clusters tend to weaken responsiveness to taxation. Corporate inventors respond more strongly to taxes than their non-corporate counterparts.

Temporary Work Agencies, Outsourcing, and Wage Inequality: Evidence from Administrative Data

Andres Drenik, Columbia University, Simon Jäger, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Benjamin Schoefer, University of California, Berkeley

Abstract: We paint a comprehensive picture of the prevalence and nature of temp agency work, its underlying drivers as well as the distributional consequences of this phenomenon. We draw on unique administrative data from Argentina that allow us to observe the universe of workers in temporary work arrangements both with their temp agency as well as the client firms that rely on their services. This unique feature – “dual registration” – combined with matched employer-employee data permits us to tackle three long-standing, interrelated questions empirically: First, we characterize the prevalence of temp agency work and outsourcing across the economy. Starting on the firm side, we describe and analyze which type of firms draw on temp agencies to outsource labor. Second, we estimate temporary work pay penalties. Here, our data permits us to hold fixed both the characteristics of the worker as well as the workplace, using data across all industries and occupations. In addition, we estimate how rent-sharing differs for workers within the same workplace that are only separated by the contractual arrangement at the same workplace and in the same occupation. Third, we investigate the economic and social mechanisms leading firms to contract out work to temp agencies, testing several core theoretical hypotheses in the literature.

Tipping Points in the Climate System and the Economics of Climate Change

Simon Dietz, London School of Economics, James Rising, London School of Economics, Thomas Stoerk, European Commission, and Gernot Wagner, New York University

Abstract: Tipping points in the climate system are a key determinant of future impacts from climate change. Current consensus estimates for the economic impact of greenhouse gas emissions, however, do not yet incorporate tipping points. The last decade has, at the same time, seen publication of over 50 individual research papers on how tipping points affect the economic impacts of climate change. These papers have typically incorporated an individual tipping point into an integrated climate-economy assessment model (IAM) such as Bill Nordhaus’s DICE model to study how the tipping point affects the social cost of carbon dioxide (SC-CO2). This literature, has, however, not yet been synthesized to study the joint effect of the large number of tipping points on the SC-CO2. SC-CO2 estimates currently used in climate policy are therefore too low, and they fail to reflect the latest research. Our paper brings together this large and active literature and proposes a way to jointly estimate the impact of tipping points. In doing so, we bridge an important gap between climate science and climate economics, and hope to bring climate policy onto more solid foundations.

“Water Trade in General Equilibrium: Theory and Evidence”

Muyang Ge, Nanjing Audit University, Eric Edwards, North Carolina State University, Reza Oladi, Utah State University, and Sherzod Akhundjanov, Utah State University

Abstract: In arid regions, rural-to-urban water markets can reduce shortfalls among high-value urban consumers by allowing irrigators to voluntarily reduce production and sell conserved water. Such sales have been criticized for reducing economic activity and the availability of water for ecosystem services in the originating region. However, there are few studies examining the theoretical rationale for such an argument against water markets, or testing it empirically. In this study, we examine the impact of a 2003 agreement in California to transfer water primarily from the Imperial Irrigation District to San Diego County, a sale billed as the largest agriculture-to-urban water transfer in US history. We develop a basic general equilibrium representation of a hydrologic-ecological-economic system to explore the theoretical effect of this trade on the economy of the water exporting region. The model predicts increases in the value of water and a decrease in employment, in both high- and low-skill sectors. We test these predictions using data on agricultural labor and production in Imperial County before and after the agreement using a synthetic counterfactual constructed using California counties. Post-2003, the divergence in crop acreage and agricultural production between Imperial County and the control closely resembles the acreage reduction requirements of the water transfers. The effect also appears in the agricultural labor market, where we show a decline in the number of both high- and low-skill employment. Increased crop yields relative to the control also indicate higher water value in Imperial County in the post-trade period. The increase in value intensified water use, and we document how greater efficiency by irrigators has decreased flows into the nearby Salton Sea, leading to corresponding declines in ecosystem services, especially habitat for migratory birds. We conclude with a discussion of the magnitude of these costs relative to the gains from water trade.

What Is the Optimal Lottery Tax?

Benjamin Lockwood, University of Pennsylvania

Abstract: Publicly-sponsored lotteries in the U.S. collect more than $60 billion annually in revenues, and are alternatively viewed as either a regressive tax on consumers who misunderstand their low expected value, or as sensible way to raise revenue for valuable public goods while generating consumer surplus. This paper studies the question of whether lotteries are welfare-enhancing, and if so, what is the optimal implicit tax rate on them? We present a model of lottery demand sufficiently flexible to allow for demand that is driven either by bias or by normatively valid consumer preferences, and we characterize the optimal implicit lottery tax (which may be infinite, corresponding to a ban) in terms of empirically estimable sufficient statistics. We then estimate these statistics using observational data on sales and lottery prizes over time, and using a new experimental survey of lottery consumption preferences.