Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

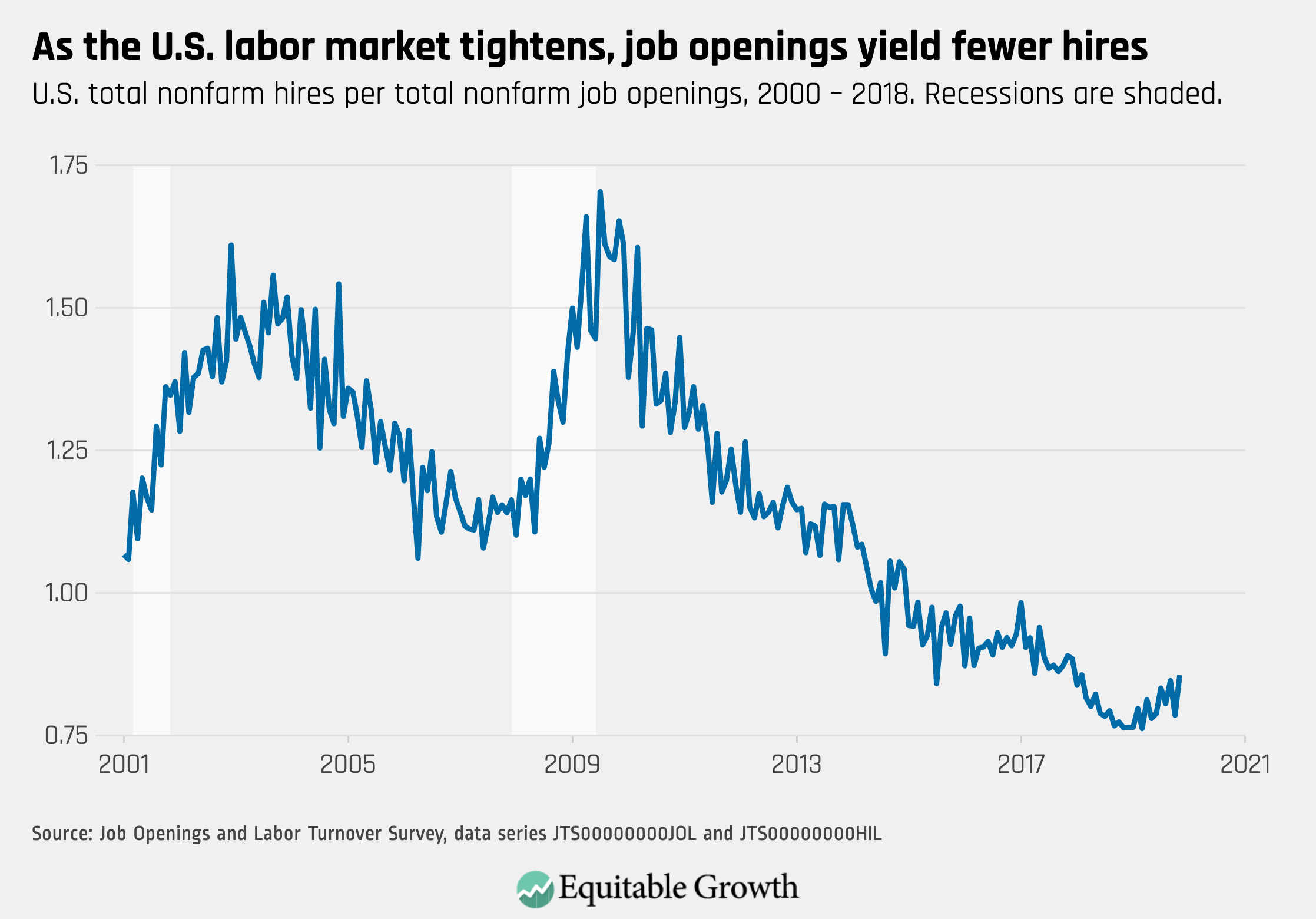

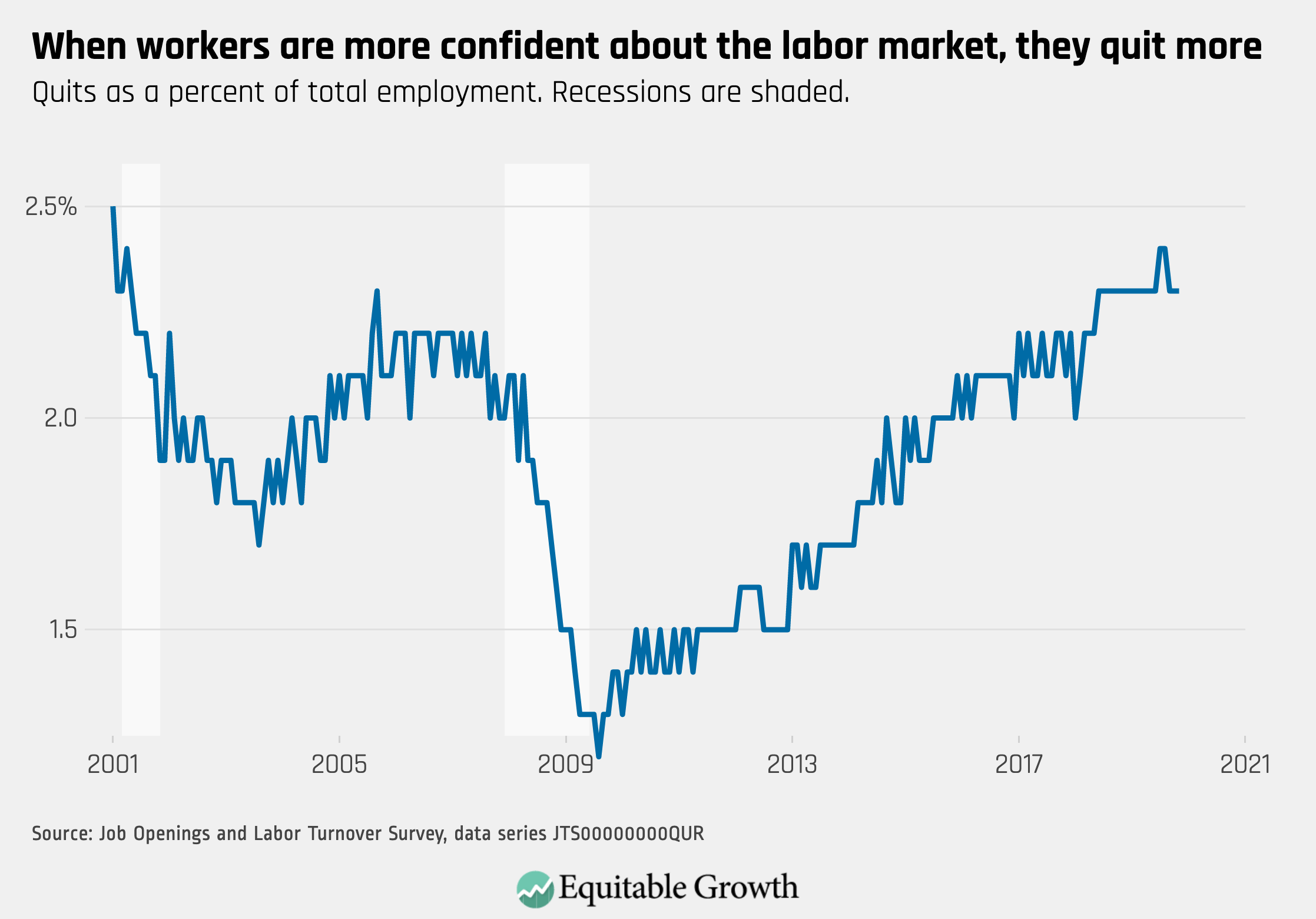

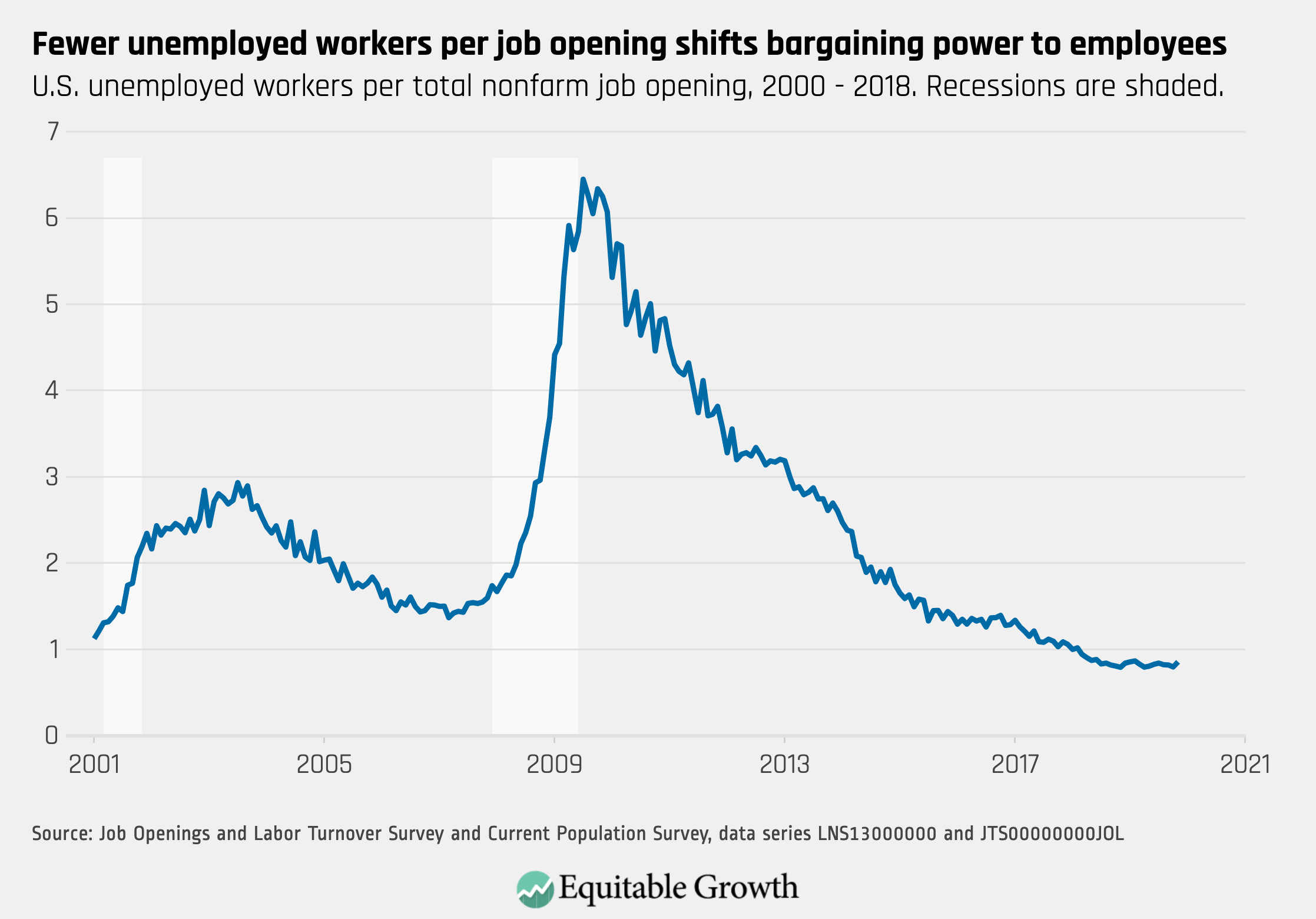

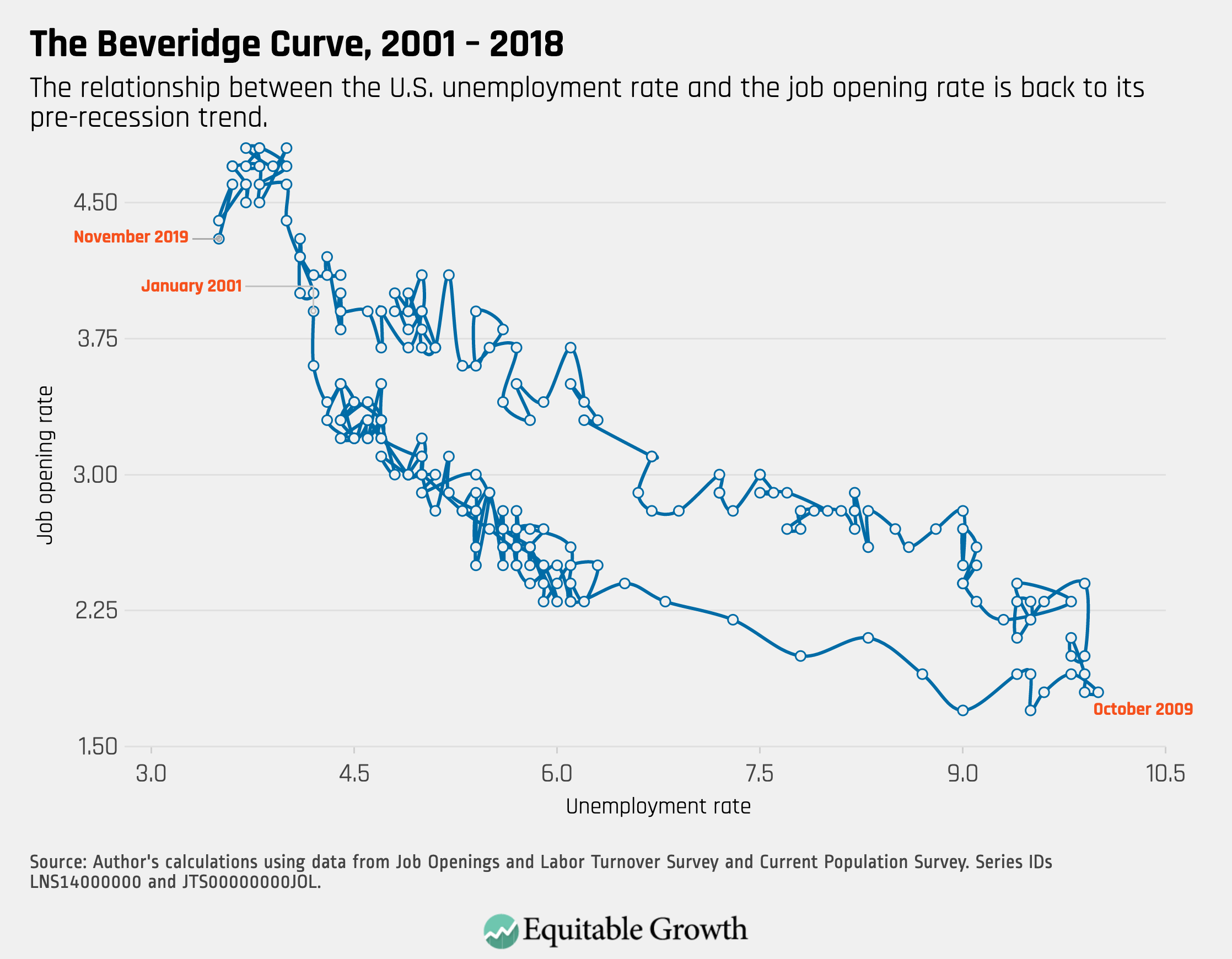

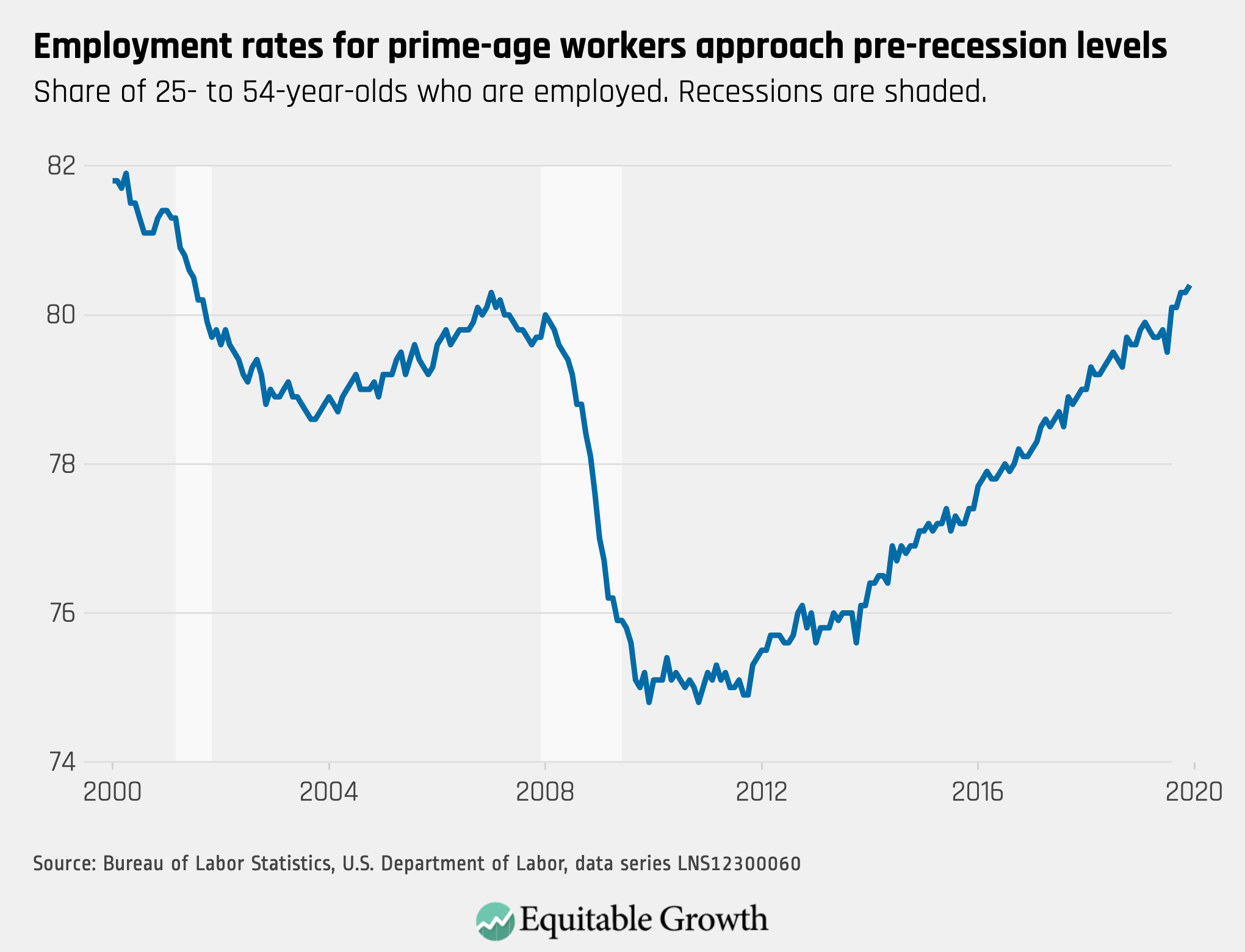

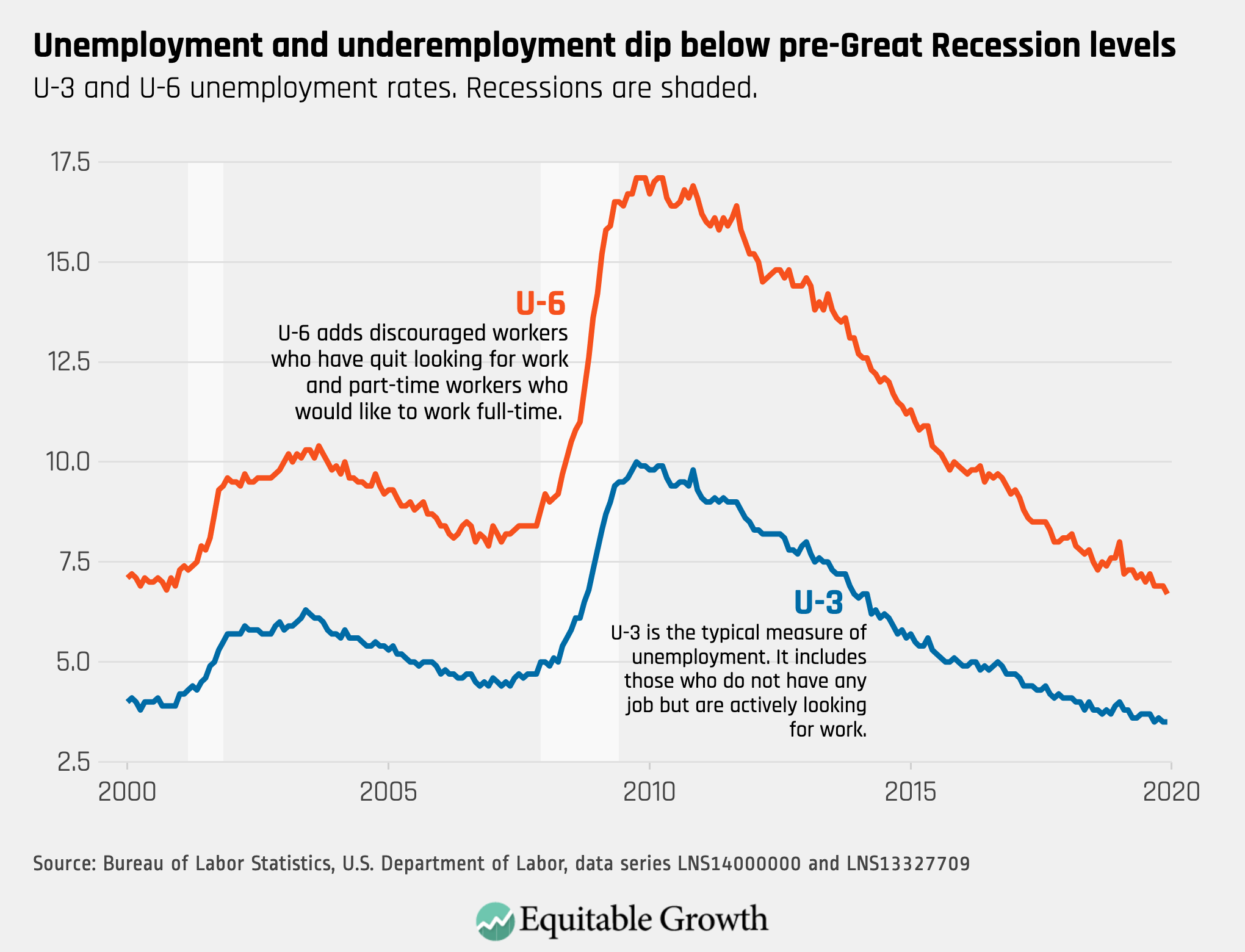

- This feature, started by Equitable Growth alumnus Nick Bunker, is always one of my monthly must-reads. The JOLTS data set is a uniquely valuable source of information. Read the latest from Raksha Kopparam and Kate Bahn, “JOLTS Day Graphs: November 2019 Report Edition,” in which they write: “Every month the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics releases data on hiring, firing, and other labor market flows from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, better known as JOLTS … This report doesn’t get as much attention as the monthly Employment Situation Report … Below are a few key graphs using data from the report.”

- Here’s a very relevant chart, titled “Racial Income Inequality in the U.S. Has Changed Little in the Past 48 Years,” from Robert Manduca’s 2018 report “How rising U.S. income inequality exacerbates racial economic disparities.”

- David Rotman at MIT Technology Review noted Heather Boushey’s book Unbound: How Inequality Constricts Our Economy and What We Can Do About It in his “The Best Books in 2019 on the Economy We Live in,” in which he writes: “The year 2019 produced some evidence-based antidotes to the trendy political narratives of robot domination and the collapse of capitalism. I’m struck by the number of truly brilliant books on economics this year. My list of favorites is below … Unbound: How Inequality Constricts Our Economy and What We Can Do about It, by Heather Boushey: Think rising levels of inequality are just an inevitable outcome of our market-driven economy? Then you should read Boushey’s well-argued, well-documented explanation of why you’re wrong.”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

- I am teaching a brand-new course this semester—brand new for me, that is, and I have stolen the concept and the readings and the organization from Harvard’s Melissa Dell. It is looking at the history of “economic growth”—both the process and the idea: “The History of Economic Growth: Econ 135.”

- The very sharp David Glasner on how Arthur Burns did a really lousy job as Fed Chair and left his successors with a horrible mess. Read his “Cleaning Up After Burns’s Mess,” in which he writes: “After prolonging monetary stimulus unnecessarily for a year, Burn erred grievously by applying monetary restraint in response to the rise in oil prices. The largely exogenous rise in oil prices would most likely have caused a recession even with no change in monetary policy. By subjecting the economy to the added shock of reducing aggregate demand, Burns turned a mild recession into the worst recession since 1937-38 recession at the end of the Great Depression, with unemployment peaking at 8.8 percent in Q2 1975. Nor did the reduction in aggregate demand have much anti-inflationary effect, because the incremental reduction in total spending occasioned by the monetary tightening was reflected mainly in reduced output and employment rather than in reduced inflation … When President Carter took office in 1977, Burns, hoping to be reappointed to another term, provided Carter with a monetary expansion to hasten the reduction in unemployment that Carter has promised in his Presidential campaign. However, Burns’s accommodative policy did not sufficiently endear him to Carter to secure the coveted reappointment … A year after leaving the Fed, Burns gave the annual Per Jacobson Lecture to the International Monetary Fund. Calling his lecture “The Anguish of Central Banking,” Burns offered a defense of his tenure, by arguing, in effect, that he should not be blamed for his poor performance, because the job of central banking is so very hard. Central bankers could control inflation, but only by inflicting unacceptably high unemployment. The political authorities and the public to whom central bankers are ultimately accountable would simply not tolerate the high unemployment that would be necessary for inflation to be controlled: “Viewed in the abstract, the Federal Reserve System had the power to abort the inflation at its incipient stage fifteen years ago or at any later point, and it has the power to end it today. At any time within that period, it could have restricted money supply and created sufficient strains in the financial and industrial markets to terminate inflation with little delay. It did not do so because the Federal Reserve was itself caught up in the philosophic and political currents that were transforming American life and culture.”