Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

- This is absolutely great news for us here at Equitable Growth, “Longtime Capitol Hill Staffer Named Policy Director at Equitable Growth,” in which “the Washington Center for Equitable Growth today announced that longtime congressional staffer Amanda Fischer has joined the organization as its new policy director. “As our new policy director, Amanda will lead the development of our policy priorities and help position the organization as a go-to resource for understanding the impact of rising inequality in the U.S. economy and what policymakers can do about it,” said Equitable Growth President and CEO Heather Boushey. “Amanda brings a wealth of knowledge and experience that will help advance an evidence-backed policy agenda to promote economic growth that is strong, stable, and broadly shared.” Fischer most recently served as chief of staff for Rep. Katie Porter (D-CA).”

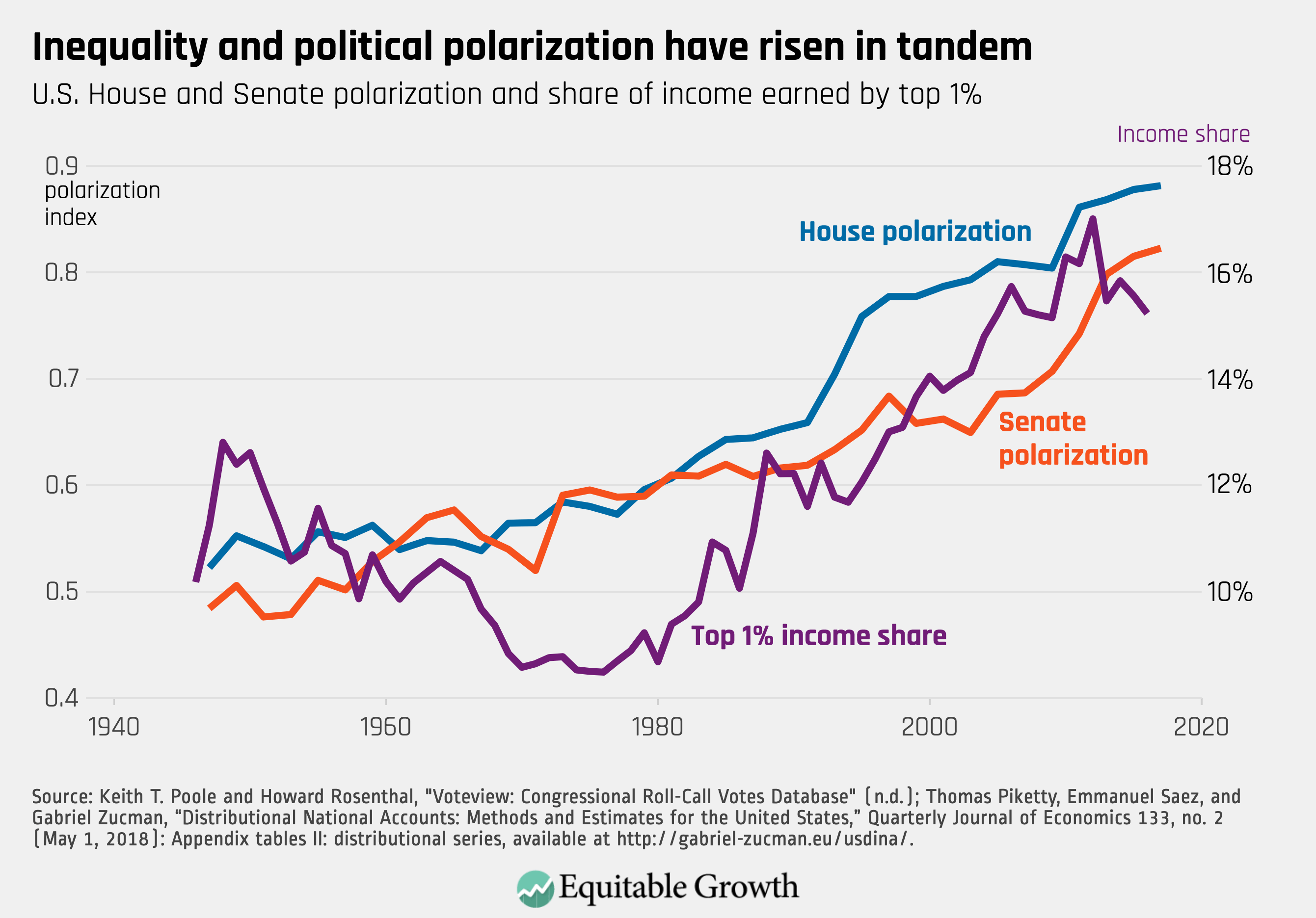

- If you are in Washington, DC do whatever you can do to get Equitable Growth’s “Vision 2020 Book Release Breakfast,” where “the Washington Center for Equitable Growth … will be releasing its new book, Vision 2020: Evidence for a Stronger Economy, at a breakfast event on February 18, 2020. Authored by leading scholars across the country, this compilation of 21 essays highlights a range of new ideas and the research behind them. We compiled Vision 2020 so the latest research informs critical election-year economic policy debates and to inspire decisionmakers to take action to address inequality’s subversive effect on broadly shared and sustainable economic growth. Building on many of the key themes and ideas from Equitable Growth’s Vision 2020 conference, this package of policy proposals tackles many of the ways that the increasing concentration of economic resources translates into political and social power.”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

- I am trying—without a great deal of success—to figure out how to teach standard economic growth theory better. Some days I feel I am making immense progress. Some days I feel like I am treading water. Some days I feel I am moving in a bad direction. I want feedback. Take a look, and tell me what you think: “Simulating the Solow Growth Model” and “Lecture Notes: The Solow Growth Model.”

- One view is that in the world of abundance we would all act as the British upper class acted, as portrayed in the books by Jane Austen. But even there the fear of descending in the class hierarchy—of failing to marry well, or marrying a husband whose gambling and debauchery debts force one out of the leisured-aristocratic lifestyle, or that one’s children might descend in the class hierarchy—is a major motivating factor keeping people acting as though they are still in the kingdom of necessity. Perhaps the lesson is that we will always imagine ourselves in the kingdom of necessity. Perhaps there are no good models for what worthwhile human life would become in an age of true abundance. Read Robert Skidelsky, “Economic Possibilities for Ourselves,” in which he writes: “The most depressing feature of the current explosion in robot-apocalypse literature is that it rarely transcends the world of work. Almost every day, news articles appear detailing some new round of layoffs. In the broader debate, there are apparently only two camps: those who believe that automation will usher in a world of enriched jobs for all, and those who fear it will make most of the workforce redundant. This bifurcation reflects the fact that “working for a living” has been the main occupation of humankind throughout history. The thought of a cessation of work fills people with dread, for which the only antidote seems to be the promise of better work. Few have been willing to take the cheerful view of Bertrand Russell’s provocative 1932 essay “In Praise of Idleness.” Why is it so difficult for people to accept that the end of necessary labor could mean barely imaginable opportunities to live, in John Maynard Keynes’s words, “wisely, agreeably, and well?” The fear of labor-saving technology dates back to the start of the Industrial Revolution, but two factors in our own time have heightened it. The first is that the new generation of machines seems poised to replace not only human muscles but also human brains. Owing to advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence, we are said to be entering an era of thinking robots; and those robots will soon be able to think even better than we do. The worry is that teaching machines to perform most of the tasks previously carried out by humans will make most human labor redundant. In that scenario, what will humans do?”